Diverse commentators, including Viktor Orbán, Noam Chomsky, Barry Posen, Peter Hitchens, Henry Kissinger and Robert Wright, have called for a diplomatic solution to the war in Ukraine. I too have been suggesting this almost since day one.

Last week, the former head of the British Army Lord Dannatt said, “Russia is not going to lose … The Russians will never go voluntarily. I can’t see the circumstances whereby the Ukrainians will ever be strong enough to throw them out.” He added that at some point Zelensky’s military commanders will have to tell him, “President Zelensky, sir, you’ve got to start negotiating.”

So what would a diplomatic solution look like? Well, it needs to be something that both sides can accept. And it should aim to preserve geopolitical stability as far as possible.

At the start of the war, I would have suggested an agreement like the one John Mearsheimer put forward in 2014: neutrality for Ukraine (no NATO integration); autonomy for the two Donbas regions; and recognition of Crimea as Russian territory. But I fear it’s too late for that now: unless defeated, Russia isn’t going to give back the Donbas.

Something along the following lines seems more realistic: the two Donbas regions go to Russia, along with Crimea; the Sea of Azov becomes a demilitarised zone; Russia withdraws its forces; Ukraine gets defensive weapons but does not join NATO. One might add further stipulations like: Ukraine must opt out of long-range missiles; and NATO must not admit new members on Russia’s border.

Now, I’m not pretending this deal is ‘fair’. And it’s entirely possible that one or both parties would reject it outright. At the present time, Russia occupies vast swathes of southern Ukraine, which under my proposal they would have to give back. So unless the course of the war changes dramatically in Ukraine’s favour, the Ukrainians are unlikely to get a better deal than this.

Why do I say the Donbas should go to Russia, and not other regions that Russia is occupying? Survey data collected prior to the invasion suggest there’s considerable support for separatism in the Donbas, but not elsewhere.

A 2014 survey commissioned by Ivan Katchanovski (the scholar who’s done all the work on the Maidan Massacre) found that a sizeable share of Donbas residents favoured some form of separatism. However, his survey found almost no support for separatism in other regions of Ukraine – contrary to Russian claims at the time.

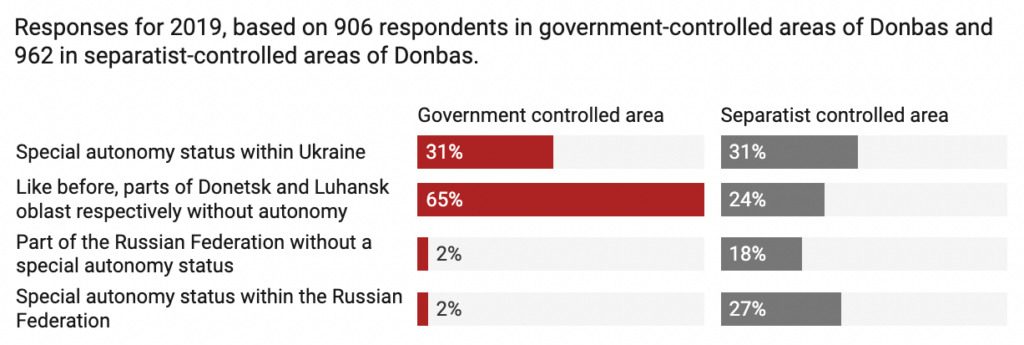

A 2019 survey commissioned by the researcher Gwendolyn Sasse yielded broadly similar results, though found dramatic differences between government and separatist-controlled areas.

A 2020 survey carried out by Sasse and her colleagues found even starker differences, with more than half of residents in separatist-controlled areas wishing to join Russia, compared to less than 15% who wished to remain part of Ukraine.

Interestingly, the latest survey from this group of researchers – carried out in January – found that 50% of Donbas residents in both government and separatist-controlled areas agreed with the statement, “It doesn’t matter to me in which country I live: all I want is a good salary and then a good pension.” Which highlights the despair people evidently feel after more than eight years of war.

Transferring the separatist-controlled areas of Donbas to Russia would help preserve geopolitical stability, while respecting the self-determination of the largely ethnic Russian population living there. However, the same cannot be said of the other regions Russia is occupying – as Katchanovski’s survey indicates.

So how would we get Russia to accept the deal? One approach would be to issue an ultimatum of the form, ‘If you reject the deal, the West will supply Ukraine with more heavy weapons’. Since supplying such weapons is what Western hawks want to do anyway, why not use them as leverage in negotiations first? Another approach would be to make the resumption of friendly relations conditional on accepting the deal.

Regarding the latter suggestion, a hawk might respond that offering to resume friendly relations is unlikely to bring Russia around, since Russia currently has the upper hand – thanks to Europe’s ongoing energy crisis. But this is all the more reason to negotiate now, rather than later, since Europe’s energy crisis will only worsen over the next few months, further undermining the West’s bargaining position.

Some commentators might find the idea of negotiating with Russia objectionable, even offensive. But they have to remember: the choice isn’t between negotiations and certain Ukrainian victory. It’s between negotiations and the continuation of fighting, which may or may not lead to Ukrainian victory, and could produce an outcome far worse.

As Hitchens reminds us, “Almost all wars end in ugly compromise.”

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Think about what powers government have over you, a few of them are:

1) they can create laws that tell you what to do and if you don’t do them lock you up

2) they can borrow endlessly in your name, and debase the currency

3) they can steal yr income/wealth at source and with the threat of imprisonment if you resist

4) finally they can kill ppl legally through wars or simply shooting citizens, remember the Brazilian chap on the tube, Iraq war or the safe and effective vaccine campaign

In no way is the current system a sensible arrangement, no one in their right mind would personally grant any of the powers listed above to anyone they knew personally, so why give them to the political class?

We live in a form of post industrial serfdom and it’s getting worse as the powers that be try to confiscate the good things industrialisation gave us, IE cars & boilers.

Point 4….Every prosecution over a death in police custody in the past 15 years has ended in acquittal…

https://qz.com/1117185/ipcc-report-in-the-uk-every-prosecution-over-a-death-in-police-custody-in-the-past-15-years-ended-with-acquittal

Fancy that

Who says its not a Police State…

I agree, except they are not creating laws, they are creating legislation. Not the same thing. Laws are much more to do with natural law and constitutional rights, but it is perhaps academic, as according to the system legal = law, and good look with trying to fight that.

Awesome. A headline which says what I have been thinking for some years now.

But its limited focus to Covid is disappointing.

I know from direct experience one stronghold of the enemy is Whitehall where career civil servants have been in post for decades undermining democracy whilst serving the commercial interests of unseen external influencers.

Few people know that Margaret Thatcher freed Whitehall from the rules restricting them developing personal relationships with individuals in commerce and industry. It marked the opening of the floodgates for corruption and that is what we have.

This even extends to use of the security services to run covert surveillance and operations against individuals in the UK to protect the profits of the drug industry.

Shocking but true.

And if there was ever to be a judicial inquiry like the Hallett inquiry we can see exactly what the outcome will be. I watched Professor Carl Heneghan’s questioning. You could cut the bias of Hallett and Counsel with a knife. Totally the opposite of the tone and approach to the previous wimpy witness [IMHO] whom Counsel and Hallett could not have been more obsequious to.

Industrialisation gave the politicians the technology to control us and we cannot give it up. Look how many walk around with it in their hands.

Every positive emotion I felt and view I held about authority (to be honest there weren’t many of either), in all their stripes have now been replaced by an attitude of distrustfulness and cynisism. Quite something to alter one’s mindset having developed it over 70+ years. Optimism has given way to pessimism and resignation. (Pass the gin bottle).

Not cynicism. Scepticism. Big difference!

It is possible to be optimistic and sceptical at the same time. Just hard work and few people like you.

I’m both a sceptic and a cynic.. Definition: Cynicism–believing that people are only interested in themselves and are not sincere. Contemptuously distrustful of human nature and motives. About sums it up I’d say.

I share a similar experience.

As a retired doctor I am ashamed of the way in which doctors have followed the narrative uncritically through fear, ignorance and gullibility and have gaslighted patients and failed to diagnose and report side effects of the vaccines. They have compounded many of the problems promulgated by government, Big Pharma, high tech, uncritical main stream media, official censors, fact checkers and propagandists, globalist cabals associates billionaires, etc.

Freedom and trust are two of the most significant casualties of the last few years.

I fear for the future.

Us ‘right thinkers’ should stick together. As Tony Hancock said in The Blood Donor episode “We could become a persecuted minority”.(regarding sharing his rare blood group. AB Negative I seem to recall).

All the power of the state comes from the systematic confiscation of money from its people.

That money accrues enormous power to the state.

State actors (politicians and bureaucrats) take money from the productive elements of society and buy favour redistributing it.

Worse still, drunk on that dynamic, they spend even more than the billions they confiscate with the effect of constantly debasing currency, which is simply another form of confiscation.

The state is evil, not least because it does all of that under the pretence of helping its population.

The confiscation of money by the state through taxes is, was always and will forever be for the purpose of giving power to those that do the confiscating.

Spot on and simply amazes me how few ppl see the truth.

Absolutely. I am inserting a post I saw back some time ago about taxes and kept. It is gob-smacking how much they rob us:

List of taxes the British are subject to :

[Forwarded from Steve Gamble – The Search For Truth]

“If I give you £1 billion and you stand on a street corner handing out £1 per second, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, you would still not have handed out £1 billion after 31 years!

Now read on. This is true and rather hard to really understand.

The next time you hear a politician use the word ‘billion’ in a casual manner, think about whether you want the ‘politicians’ spending YOUR tax money.

A billion is a difficult number to comprehend, but one advertising agency did a good job of putting that figure into some perspective in one of its releases.

1. A billion seconds ago, it was 1991.

2. A billion minutes ago, they claim Jesus was alive.

3. A billion hours ago, our ancestors were living in the Stone Age.

4. A billion days ago, no-one walked on the earth on two feet.

5. A billion Dollars ago was only 13 hours and 12 minutes, at the rate our present government is spending it.

We are charged:

· Stamp Duty

· Tobacco Tax

· Corporate Income Tax

· Income Tax

· Council Tax

· Unemployment Tax

· Fishing License Tax

· Petrol/Diesel Tax

· Inheritance Tax (tax on top of tax)

· Alcohol Tax

· G.S.T.

· Property Tax

· Purchase Property Tax

· Tax on Title Searches

· Tax on Building Inspections

· Tax on supplements

· Taxes on various food items

· Taxes on Dining out

· Tax on all utilities – Phone, hydro, water, waste disposal

· Service charge taxes

· Social Security Tax

· Vehicle License / Registration Tax

· Vehicle Sales Tax

· Workers Compensation Tax

· And now Carbon Tax

AND I’m sure you can think of more……

STILL THINK THIS IS FUNNY?

Not one of these taxes existed 60 years ago, and our nation was one of the most prosperous in the world.

We had absolutely no national debt.

We had the largest middle class in the world. A criminal’s life was uncomfortable. What on earth happened?

I hope this goes around the UK.

#GovernmentCorruption”

That is brilliant, I have forwarded it on to so many people. Government is a parasite

A parasite fed by the people who were out in the streets banging pots. They are the real enemy.

In the Beatles song “The Taxman”, they joked of taxing the air, which they probably thought was quite funny and even John Lennon would have thought this would never happen——-But here we are 43 years after his death taxing the air (Carbon tax)————-PS Great comment

This is a fantastic book by Dominic Frisby BTW..

Daylight Robbery: How Tax Shaped Our Past and Will Change Our Future https://amzn.eu/d/hKPkgp1

Frisby discuss the taxation at source is one reason there will not be a revolution..

https://youtu.be/HwT7RtN44Fc?si=iPfuIULYPlbChKY5

I agree there won’t be a revolution. The only way this ends is in collapse. That’s not only possible, it’s inevitable. What that collapse looks like is what is uncertain.

Russell Brand keeps quoting Julian Assange, so I will too

“The purpose of government is to take public money and put it into private hands”.

As Ayn Rand says, polticians should never be allowed anywhere near the economy. The government gets away with this because there is an every growing number of people who depend on the government and are now incapable of taking responsibility for themselves. Once a political party starts down the route of socialism the rest eventually have to follow if they want to get elected.

One of the greatest foci of resistance to the corona programme has been lawyer Rainer Füllmich who has collated all the evidence against Big Pharma and western governments, especially the EU. So he has been arrested and, like Julian Assange, sits in prison – currently in Göttingen, Germany.

Rainer Füllmich speaks from prison on http://www.bittel.tv, posted yesterday on Telegram at 22.37. Füllmich´s report, recorded on Oct. 15th, begins at 30 mins. in.

He reveals that Vivienne Fisher, probably a CIA plant, has looted the ICIC´s money and written a book full of “invention” – and then had the temerity to sue Füllmich for embezzlement! Füllmich´s rebuttal is eloquent and comprehensive, backed up with proof on every detail.

This looks like an attempt to destroy Füllmich (like Assange) before the dénouement at IC4 in Bukarest on Nov 17th/18th. But it seems the powers that be have met their match in Füllmich.

If anyone on the sceptical wing overplayed their hand it was Fullmich.

I still find his description of a decades-old plan by global elites to create conditions for control of the world’s population thoroughly believable – but it seems he got caught with his fingers in the till (https://www.vice.com/en/article/93kzep/reiner-fuellmich-arrest-fake-pandemic-conspiracy-lawyer-arrested). Shame. Always wondered why he made such an impact several years ago, inspiring many, including me, with hope – and then just disappeared. But who knows – it’s entirely likely that the accusations of embezzlement are trumped up, Epstein-style.

Hi Clive. Please read again the post you are responding to by ekathulium.

The ‘fingers in the till’ allegation was addressed in that comment:

I appreciate you did add “But who knows – it’s entirely likely that the accusations of embezzlement are trumped up, Epstein-style.“

But Epstein did all the other stuff he was accused of? So why make that comparison when it seems inappropriate.

Perhaps it was inadvertent?

Web server was down at 11.12 a.m. on 20/10/2023.

I remember the Füllmich and team in an interview with Dr Mike Yeadon and Dr Claire Craig back in 2020 I think. It was on Youtube, linked from the BMJ.

“But anguished despair, if you were a caring, concerned citizen who loves individual freedom and autonomy.” No, just a deep, abiding and irreparable distrust and hatred of central and local government, the judiciary, the police, the NHS, academia and the education system, the MSM especially the BBC, and the pharmaceutical industry in which I worked for much of my career and from which I draw a pension.

There has long been a symbiotic relationship between government their scientists. Government will justify all they do because they are allegedly “following the science”. And when it all goes wrong it was the fault of the “scientists” and they get off Scott Free

“just a deep, abiding and irreparable distrust and hatred”

If they behaved with honour and honesty that distrust and hatred would not exist.

But sadly they don’t.

And politicians wonder why so many people don’t vote for them.

People are hungry for honesty and honour in politicians.

“Let them eat cake.“

“…in the last three years, so many gave up freedoms to [- so they were told -] prolong lives”

We need a wholesale and radical change to our system of government. We don’t need new parties as they all seem to gravitate towards the same agenda. The endless Labour/Tory punch-and-judy show is a pointless exercise, yet many still see it as their only option when it comes to voting. We need less government, government of just the national essentials such as protection of borders and basic infrastructure. The problem is, the existing system will continue as long as voters keep accepting it without even considering other possibilities. The status quo will remain until the voters themselves get tired of being constantly lied to, duped, and abused.

How many politicians do we hear say “We need change”. ——–What do they mean by “change”? It doesn’t mean anything. This is what politicians do. They talk endlessly but say NOTHING

I wouldn’t accuse Reclaim or Heritage Party of gravitating towards the same agenda.

Why not? If they are not doing it now they will eventually surely?

It is just the way things are and have become.

In the end, governments act to protect the ‘state’ apparatus rather than the actual nation of people they are meant to serve. People are irrelevant to the state, more a resource to be squeezed for every ounce of labour and tax they can extract to support the ‘state’. In the new world they want to create (but won’t), nation states are also irrelevant. It is clear that our government system needs to be overhauled. We want small government, less bureaucracy, smaller civil service, less tax, more say in what they spend our money on etc. How that happens is the question. At the moment, the government really is the enemy of the people and we, the people, are the enemy of the state!

The state is controlled by the bankers and big corporations. The politicians are just following instructions.

Depressingly true. Sadly it was only likely to be a dry run for the planned climate change lockdowns.

What the clowns at the WEF failed to realise was that they overdid the Covid measures and there are now many people who know what’s going on (hence the recent batch of censorship bills around the world). They have to silence us to prevent losing their grip.

We need to get rid of every WEF shill who currently masquerades as an MP.

Naming and shaming them all might be a good first step?

They are not all aware but most by now are just not scared about c19. It has past its shelf life. Remember in the Canadian Parliament when one MP asked who is a member of the WEF. The Speaker’s microphone suddenly stopped working. I’m sure it was a great question he said.

Look at the message – you will own nothing and be happy. I believe that they know that the present economic system cannot continue and their main objective is to protect their assets. They believe they can do that by taking everything we own. They are trying out how far they can go with covid and the climate, before the final push. I suspect they are too afraid to take the final step, but they cannot reverse the economic chaos they have created. We will all suffer in the end.

COVID was the public downfall of western parlamentarism, which turned out to be LDINO — liberal and democratic in name only. When push comes to shove, constitutions are just toilet paper for the governing class and clever lawyer types can make legally sound arguments for turning all of our so-called rights into the exact opposite of what they were meant to be. It makes sense to have some sort of parliament as representation of the people when dealing with the government. The idea of parliament governing itself is institutionally insane.

If you are fed up with the Uniparty status quo, then sign the Pledge at https://notourfuture.org

Thanks for the link.

Signed.

“The existing frameworks, processes and institutional safeguards under which liberal democracies operated until 2020”

Shouldn’t that be until 2001/911?

The 1963 Kennedy assassination shows it has been going on for a very very long time. It is more sophisticated now.

But they still don’t care that their legends to cover up are full of holes as long as enough people believe them for long enough.

The whole premise of this article is that everything over the last three years evolved organically – there really was a pandemic and governments, health authorities and even the WHO all tried their best in difficult circumstances – they made some bad mistakes and were overly authoritarian, but it was all with the best of intentions. The media decided that public health would benefit if they didn’t question every policy proposal or whether vaccines were actually safe and effective. They made a mess of things, but their heart was in the right place. Incompetence rather than conspiracy.

But we surely know that none of that is correct, don’t we? This was all planned. Lockdowns and masks were introduced to ensure the new mRNA vaccines would be taken up by “everyone”. The facilitation of digital IDs and possibly even depopulation were part of the plan. The media and regulatory agencies were captured.

Etc, etc, etc

Depopulation is what is pushing everything that the Davos Deviants are doing.

Ironically the highest birth rates are in the poorest countries. Once people become prosperous their birth rates fall to levels seen in the wealthy west. And the only way they can become prosperous and develop is by using the same fuels as we did. —-Coal Oil and Gas. —-But poor people are denied those fuels and told to leave those fuels in the ground and we fob them off with some money for turbines, which means they will stay miserable and poor and birth rates will remain high.—— So if depopulation is the goal, ironically the best thing to do is allow fossil fuels. The people become more educated, they live more organised lives, they use birth control ad birth rates fall dramatically. —Climate Policies harm the poorest.

And remember they are now admitting HQC is an effective treatment, yet in parts of Africa, Japan, India etc they were using it. Handcock even said in Parliament that vitamins are not the answer. And don’t forget how they tried to discredit any Dr that used Ivermectin.

Why did George Osborne as Chancellor increased national debt from £900 billion to £2.1 trillion under the cover story of implementing austerity under which our national debt should have decreased?

Isn’t it all about putting us all into debt so that when government needs to borrow more we have to accept the conditions imposed by the rich international financiers and accept even more of the crap that is already being forced upon us?

This jack boot story focusses on covid and ok fair enough. But the other Big C (Climate) is the one that really has us by the balls and started way back in 2008 with the Climate Change Act and is ongoing with impoverishment coming along the line faster than HS2. Watch you wallets people, and make sure you get half a dozen jumpers from Santa.

Letter currently being sent to parents of schoolchildren telling them: “Covid-19 vaccination has a proven safety record. It gives better protection than any immunity from a previous infection.”

From:

Dr Nikita Kanani MBE, GP,

St John’s Medical Director of Clinical Integration,

NHS England Deputy SRO,

NHS COVID-19 Vaccination Programme

Visiting Professor, School of Medicine, University of Sunderland

Same wording about safe and effective is in an email from this evil woman [IMHO] sent recently to all over 65s.

Compare to what Andrew Bridgen said in Parliament yesterday about the people still being killed by these injections:

FULL TRANSCRIPT OF ANDREW BRIDGEN – FROM HANSARD THE OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS IN PARLIAMENT

Watch the debate here:

https://twitter.com/chrislittlewoo8/status/1715402213839740956

The tyranny has only just started.

If you don’t resist now, you never will.