Mask-wearing had no discernible impact on the spread of COVID-19 in Europe during winter 2020-21 and may actually have increased mortality, a study has found.

The peer-reviewed study by Professor Beny Spira from the Department of Microbiology at the University of São Paulo, published in the journal Cureus, looked at the correlation between the rate of mask-wearing in the population and the number of reported infections and deaths from October 2020 to March 2021 in 35 European countries. All European countries, including Western and Eastern Europe, with more than one million inhabitants were included, encompassing a total of 602 million people. All the countries experienced a peak of COVID-19 infections during the six months – the winter 2020-21 wave.

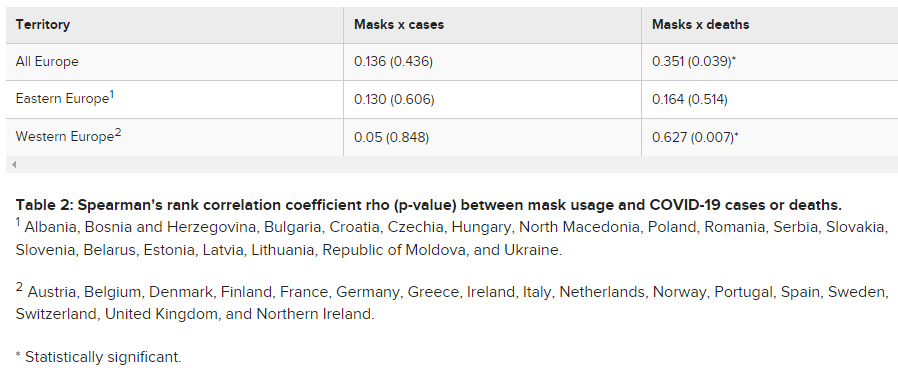

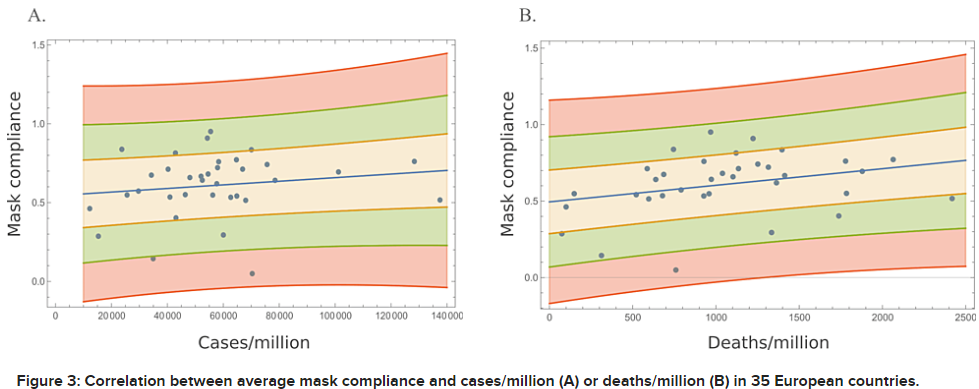

The results are shown in the graphs above, where a positive correlation can be seen in the case of both infections and deaths, i.e., greater mask-wearing went hand-in-hand with more infections and deaths, the opposite of the intended effect of masks. In the case of reported infections the correlation was not statistically significant, so may have been by chance. In the case of deaths it was statistically significant, particularly in Western Europe, opening up the possibility that wearing masks actually made things worse.

Professor Spira addresses some possible limitations of the study.

It could be argued that some confounding factors could have influenced these results. One of these factors could have been different vaccination rates among the studied countries. However, this is unlikely given the fact that at the end of the period analysed in this study (March 31st 2021), vaccination rollout was still at its beginning, with only three countries displaying vaccination rates higher than 20%: the UK (48%), Serbia (35%), and Hungary (30%), with all doses counted individually. It could also be claimed that the rise in infection levels prompted mask usage resulting in higher levels of masking in countries with already higher transmission rates. While this assertion is certainly true for some countries, several others with high infection rates, such as France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain had strict mask mandates in place since the first semester of 2020. In addition, during the six-month period covered by this study, all countries underwent a peak in COVID-19 infections, thus all of them endured similar pressures that might have potentially influenced the level of mask usage.

Professor Spira notes the findings are in line with the results of most randomised controlled trials before and during the pandemic, which found the “role of masks in preventing respiratory viral transmission was small, null, or inconclusive”. Despite this lack of evidence, masks were widely mandated.

Mask mandates were implemented in almost all world countries and in most places where masks were not obligatory, their use in public spaces was recommended. Accordingly, the World Health Organisation (WHO) as well as other public institutions, such as the IHME, from which the data on mask compliance used in this study were obtained, strongly recommend the use of masks as a tool to curb COVID-19 transmission. These mandates and recommendations took place despite the fact that most randomised controlled trials carried out before and during the COVID-19 pandemic concluded that the role of masks in preventing respiratory viral transmission was small, null, or inconclusive.

Mask proponents appear to have been led astray by population-based studies from 2020, where, the study notes, ‘mask effectiveness’ was invariably measured against a background of falling infections.

Conversely, ecological studies, performed during the first months of the pandemic, comparing countries, states, and provinces before and after the implementation of mask mandates almost unanimously concluded that masks reduced COVID-19 propagation. However, mask mandates were normally implemented after the peak of COVID-19 cases in the first wave, which might have given the impression that the drop in the number of cases was caused by the increment in mask usage. For instance, the peak of cases in Germany’s first wave occurred in the first week of April 2020, while masks became mandatory in all of Germany’s federal states between the 20th and 29th of April, at a time when the propagation of COVID-19 was already declining. Furthermore, the mask mandate was still in place in the subsequent autumn-winter wave of 2020-2021, but it did not help preventing the outburst of cases and deaths in Germany that was several-fold more severe than in the first wave.

The study concludes that the lack of negative correlations between mask usage and COVID-19 reported infections and deaths suggest that “the widespread use of masks at a time when an effective intervention was most needed, i.e., during the strong 2020-2021 autumn-winter peak, was not able to reduce COVID-19 transmission”. It adds that the moderate positive correlation between mask usage and deaths in Western Europe suggests the practice “may have had harmful unintended consequences” – though cautions that no cause-effect conclusions can be drawn from the observational analysis.

The study is worth reading in full.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.