We’re publishing an original essay today by Dr. Paul Jones, Head of History at an independent school, to mark St. George’s Day. Dr. Jones takes issue with the fashionable view that Britain’s history is an unbroken litany of oppression, exploitation and self-deception and points out that, while we bear some of the responsibility for the horrors of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the British were hardly alone in participating in slavery, and, unlike other nations, we were at the forefront of abolishing that trade.

First, Dr. Jones focuses on the debit side of the moral ledger.

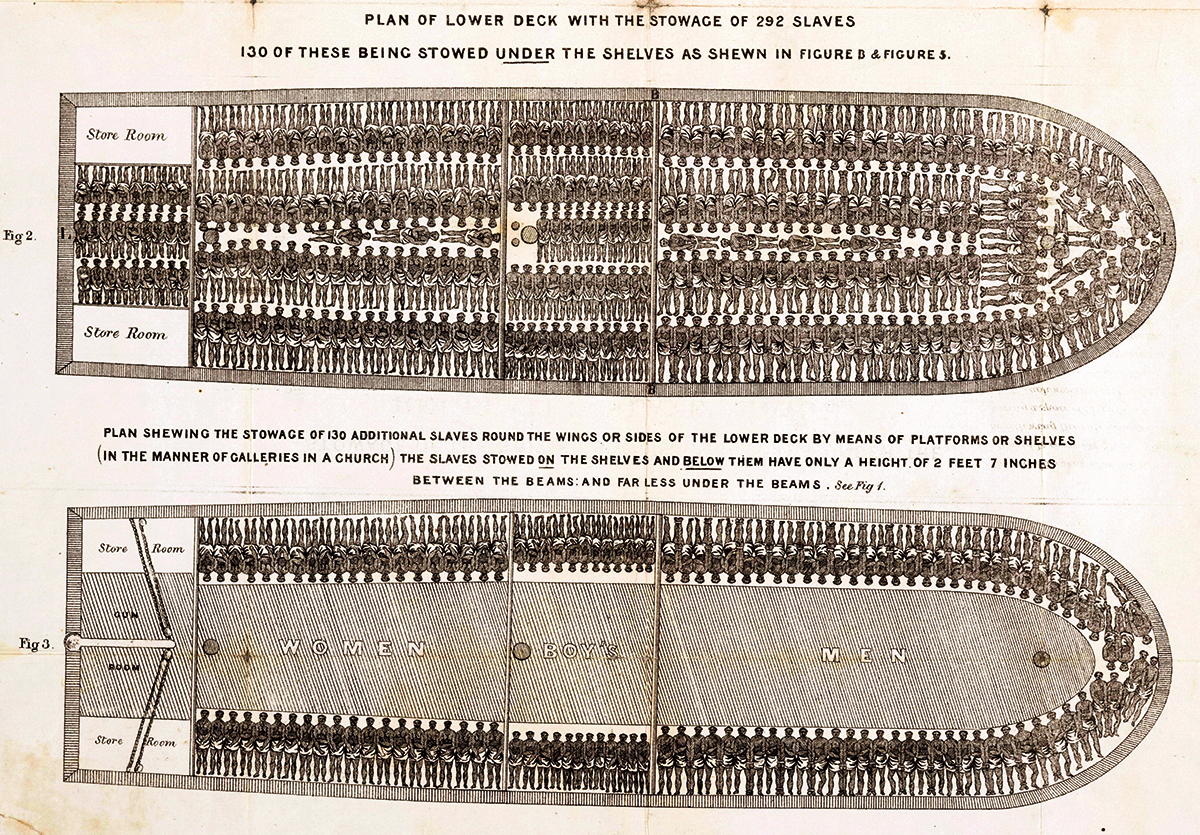

According to Martin Meredith, Britain was responsible for the trafficking of over 600,000 slaves from Africa to America between 1791 and 1807. The National Archives suggests that Britain transported 3.1 million slaves between 1640 and 1807, though some estimates put the figure far higher at 12.5 million and the UN suggests about 15 million people were shipped as slaves across the Atlantic. Conditions on board slave ships, known as ‘Guineamen’, were utterly horrific, with slave traders cramming as many people below deck as possible to maximise potential profit and offset the costs of those who died during the Middle Passage. From the 1500s to the 1800s, 10% to 30% of slaves being transported died in the cramped and insanitary conditions of their ships. As Olaudah Equiano’s account of his experience of the Middle Passage shows, treatment of slaves was predictably brutal as slaves were regarded as cargo rather than humans, with floggings and beatings being used to maintain control. Even worse things could happen. One infamous incident occurred in November 1781 when the crew of the British slave ship Zong threw over 130 slaves into the sea to save food and water and strengthen their case for an insurance claim. Arrival in America and living on a plantation was hardly any easier either. Disease was rife and one in three slave children died before the age of 10. Slave owners handed out all manner of horrendous punishments to those who resisted or tried to escape.

He then contextualises this by pointing out how many other countries and empires have been involved in slavery throughout history.

The truth of the matter is that England arrived relatively late to the slave trade. Slavery had existed for thousands of years before England engaged in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Ancient Egypt relied on slave labour for construction projects, notably the pyramids, and ancient Greece likewise made use of slaves – Herodotus claimed slaves, known as helots, outnumbered free people by as many as seven to one in ancient Sparta. The Roman economy heavily relied on slaves too. Viking raiders enslaved people in any area they targeted, whilst Arabs began enslaving people from Africa from about the ninth century, establishing the trans-Sahara slave trade. Arab slave traders continued to be prolific in East Africa throughout the 19th century, and pirates from North Africa enslaved at least one million European people between 1500 and 1800. Slave labour provided the power source for the galleys deployed by Italian city states and the Ottomans for centuries and proved crucial in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. Roughly 6.5 million people were enslaved and shipped across the Black Sea from 1200 to 1760.

English people were themselves subjected to the terror of slavery as the coastline of Britain was frequently targeted by Barbary pirates. So severe was the problem that it was stated in the Calendar of State Papers in May 1625 that “the Turks are upon our coasts. They take ships only to take the men to make slaves of them”. Raids by Barbary pirates became so problematic that Parliament established the Committee for Algiers in December 1640 to deal with the ransoming of those who had been taken into slavery. Edmund Carson was sent to Algiers by Parliament in 1645 to negotiate the release of English people taken captive and he ended up spending the final years of his life trying to secure the liberty of further English slaves. Yet, despite Parliament’s efforts, North African pirates continued to terrorise England’s coast until combined British and Dutch military forces finally stamped the problem out in 1816 and freed 4,000 slaves in the process.

Finally, Dr. Jones describes Britain’s efforts to stamp out the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

The Royal Navy was deployed to actively suppress slave trading and in 1808 the West Africa Squadron was formed under the command of Commodore Sir George Collier to hunt down and intercept ships involved in slave trading. Some £4 million was spent from 1870 to 1890 maintaining naval forces off the coast of East Africa for the purpose of suppressing slave trading. This would equate to £547 billion in today’s money being spent on efforts to fight for freedom, whereas the U.K. Government has perhaps spent anything from £310 to £410 billion on efforts to restrict freedom through Covid measures. Average GDP from 1870 to 1890 was £1.259 billion and defence spending during that period typically constituted £0.03 billion, or 2.38% of GDP (Britain has often spent about 2% of GDP on defence in recent years). Maintenance of anti-slavery patrols on East Africa alone thus accounted for about 0.015% of GDP or 0.634% of defence spending, and all done with just a fraction of the number of bureaucrats we have today. Whilst it may be true that only a small percentage of slave ships were intercepted by the Royal Navy, perhaps less than 10% by the West Africa Squadron, and some might complain that Britain should have committed more resources to the task, the fact of the matter is that Britain made a clear effort (and a far greater one than any other country) to suppress slave trading. That effort yielded results. Around 1,600 slave ships were intercepted by the Royal Navy between 1808 and 1860, liberating about 150,000 slaves. Liberated slaves often ended up joining the Royal Navy and were themselves involved in freeing other slaves. Between 1866 and 1869, a further 129 slave ships were captured and another 3,380 slaves were freed. Action by the Royal Navy in 1873 shut down the slave market in Zanzibar and British Governor-General, Charles Gordon, made concerted efforts to end the slave trade in the Sudan. It was after Khartoum was captured and Gordon killed by Mahdist forces in January 1885 that the slave trade grew again. British anti-slave trade operations continued into the 20th century, with British action suppressing the slave trade in Tanganyika in 1922. One simply cannot ignore or deny the fact that Britain was at the forefront of the anti-slave trade movement.

Worth reading in full.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Why should a whole nation have to pay? Surely we can check the historic records and get the names of the owners of the ships and the owners of the cargo.

If you check the records, you will find that the slaves were sold to the shippers by their own compatriots, who are at least as guilty as the British…

where are these records you claim to have checked? Who has these records? Or are you bluffing,i’d bet a pound to a penny yoy’ve never seen any of those records. The first step to redeeming you nation is to accept what you you did and quit hiding behind lies.

where are these records you claim to have checked?

Where do I say that I have checked any records?

The first step in any discussion is to read what is written, which you have not done. besides, your nation is just as guilty – if not more so. What did you do to stop slavery?

I’m inclined to think you’re right, but actually the words “If you check the records you will find…” do plainly imply that you yourself have checked them. The way to counter ‘lordsnooty’ is simply to provide a source for your claim.

the words “If you check the records you will find…” do plainly imply that you yourself have checked them.

No, they do NOT!

They imply that I know what you will find – though that knowledge may well be gained from other sources.

For example, I may say that if you check the records of water height at Tower Bridge, you will find it going up and down. This does not mean that I have ever checked them – it means that I know that the Thames is tidal at that point….

That’s really along the lines of::

when you turn up with advanced weapons and cheap commodities that are valuable to the incumbants your effectively taking advantage and exploiting the locals.

Large parts of the world exist on far less than $10 a day, I you brought 5 of them to the UK and paid them $20 a day for 8hours work that would be considered modern slavery even though your paying double their local rate & likely easier work.

Saying their own compatriots sold them out completely ignores the fact that those sales would not have happened if British where not buying.

It strong today & was wrong back then.

Saying their own compatriots sold them out completely ignores the fact that those sales would not have happened if British where not buying.

Quite right. They would have been killed as sacrifices. Being shipped as slaves gave them more chance of living.

I don’t think you understand how African tribal society worked. Members of enemy tribes were routinely captured and killed. Selling them as slaves was advantageous for both captive and captor…

Absolute bollocks.

so by your reckoning it would have been ok for the UK to have enslaved those the NAZIS where slaughtering in WWII?

the vastness of Africa wasn’t 1 country or 1 culture all operating the same way.

you just present narrow minded viewpoints to promote your own world view.

its a bit like having a jab because some false study that actually was a letter to some journal said it’s ok, when actual other data showed it was at best pointless and at worst dangerous but no one would look at that data because it wasn’t a popular view and against national or regional interests.

Get a decent education. The one you have isn’t working.

There you go the reasoned debate of an intellectual.

perhaps some more mung beans for your broth tonight and some extra scratchy hair for your shirt.

on the topic of education yours clearly wasn’t complete, I will be generous and assume you where not paying attention, the alternative being you simply didn’t understand what you where taught and continue to struggle in that department today. .

Yes, I remember the story about the native of Tanganyika in Roald Dahl’s Going Solo.

A wage is not an absolute amount, it is purchasing power. Purchasing power in London for accommodation is minimal.

A living wage will cover the costs of accommodation, heating and lighting, food and water, being adequately clothed and shod, being able to socialise in a temperate manner and being able to enjoy some simple pleasures of life.

Oh, and to put a bit by for a rainy day.

Wages around the globe are entirely non-comparable, because the costs of living are likewise incomparable.

Why would anyone have to pay? Why is it even a subject? the slave trade in white people by Arabs and Africans isn’t discussed.

Neither is it much discussed that here today, and for at least 30 years, gangs of men of predominantly Pakistani origin, are sex-enslaving mainly white schoolgirls.

Of course, as the Pakistani men will vote for the Labia Party and schoolgirls don’t vote, that’s fine. All in the interests of diversity.

With the obsession of racism no one can discuss race realism, or perhaps cultural realism.

As time goes on we will test the hypothesis all the immigration is based upon, that immigrants become British. Time will tell.

“Racism” is now just a weapon used the International Extreme left used to destroy Bourgeois western society .

When are we going to talk about Chinese “racist attitudes? Or the way Arabs treat their Filipino and African servants?

Not great for the “slaves” in Qatar, I heard. Apparently some two thirds of the population are foreign nationals.

As you are no doubt aware it is just propaganda. A background noise that goes unexamined by most. Say it often enough and our inhumanity becomes accepted.

Covidmania taught us facts have little bearing on a narrative. I don’t think this one will work as it is too far away in time. But it will convince the masses we have some sins to atone for. At least right up until economic collapse that is, then the woke will be given a lesson in why spending your life agonising over historical events doesn’t put food on the table.

The woke, normies and sheeple are going to get a very rude awakening soon. Maybe not; I wonder if they’ll ever realise why they are dying. They behave like cattle, happy munching in their field, that nice man brings them hay when the grass is short. They become a little confused about the cattle truck but it’s ok that nice man is herding them in there. They wonder what the slaughter house is about then die in their confusion about where they are.

Beware the smiling, cackling Billionaire Philanthropist, waving a syringe!

Because it involves wrongs done to White People – which don’t count – simple!

This is an impossible form of moral economics: a complete waste of intellectual energy that creates resentment all round.

It might be worthwhile concentrating our efforts instead on making the most of ourselves (which just can’t be done by those encouraged to have a victim mentality).

Along the way there will be co-operation and agreement, and competition and disagreement; but at least it won’t be (if DS will pardon the expression), a pointless wank.

.

“This is an impossible form of moral economics: a complete waste of intellectual energy that creates resentment all round.”

That’s the point.

Diversion into permanent “guilt trip” while we are being stuffed over by the Global Elites like never before!

I agree.

Quite.

We can’t rewrite history.

Don’t say that to historians!

I don’t mind how many versions of history there are. People have different perspectives and it’s interesting to see them.

But I object to facts deliberately ignored in order to make a case and to wilful ignorance about historical context for the sake of moral grandstanding.

History teaches us that history quite often needs to be rewritten. One of the key points that is often missed today is that history is fundamentally different from science, and thus historical science (and modelling) different from actual observational science.

History teaches us that it was written by the winners. And when journalism, aka the first draft of history, is made up drivel produced by propaganda merchants, the chances of historical facts being anything but pure fiction are very small.

No you can’t. Can I rape your daughter and say that ‘everyone was doing it, including Muslims and black people, so it doesn’t matter!’ ?

>creates resentment all round

you certainly resent it, I can tell that!

I’m not sure that I resent it personally, perhaps because I’ve never been on the receiving end of it myself!

But it does mightily annoy me, because I’ve seen people distressed by unfair accusations, and others who have become whining parodies of what they could be if they would only stop blaming everyone else (including the long dead) for their problems.

Aren’t most of them related to the current “Ruling Elites”?

Quite. Are the Italians, Greeks, going to have to pay for their skav8ng days? Then there’s the Norwegians and their ancestral Viking shaving exploits on this island.

(In that film about the vikings, I think it was Kirk Douglas who insisted on being the only clean shaven one amongst all the beards )

)

If I became aware that my elders had been transported like this, I’d go after all the whities to teach them what’s what!

If I became aware that my elders had been transported like this, I’d go after all the whities to teach them what’s what!

Your ‘elders’ WERE treated like this. Slavery was common to ALL cultures back in the day. Until the British put a stop to as much as they could…

I told you, my ancestor helped with the feeing of English slaves in North Africa in the 18th century. Admittedly the slave triangle business was more recent, but still 19th century, when the British working class were treated appallingly. What about my ancestors down the lead mines?

I wonder if those connected to the English slaves in North Africa in the 18th century were ever paid any compensation….

(I should add that things were so bad for some people in 19th century industrial England that it was dubbed “white slavery”).

I feel neither pride nor shame about what my ancestors did and in any case my ancestors were probably working in the fields.

Indeed. I got a fair way back in my ancestry on my father’s side and things were tough back then for the working stiff. Even my paternal grandfather had a hard life compared to my father or myself.

Indeed – life for a factory worker or field worker was not really that much worse than for a slave. My family were labourers going back several generations- they benefited nothing from the slave trade, other than moving from working themselves to death in the fields to working themselves to death in the factories as the industrial revolution swallowed the land they worked.

The only beneficiaries of the slave trade were exactly the same 1% who continue to screw the peasants to this day. And that 1% includes – very near the top – the African tribal leaders who ran the trade in their neighbours souls long before and long after the British Empire was involved.

Valuable comment.

Exactly! And a few centuries before they would have probably been serfs – bonded labourers tied to the Manor and the land……in effect “slaves”. If we are talking slavery we need to address the Ruling Class since 1066 .

As ” Digital,Techno Feudalism” is what Schwab and Co have in mind for the ‘plebs’ perhaps we should take a look at them first? We know that Schwab’s father made giant turbines for the Nazi Heavy Water nuclear weapon project in Norway …and we know that much of German wartime labour was slave labour, using prisoners of war and transported civilians from the East.

The word “slave” is derived from slav of course, as there were so many Slav slaves it the late Roman Empire.

The contemporary slave trade has of course not been stamped out as the article claims – it is just never talked about.

“Exactly! And a few centuries before they would have probably been serfs – bonded labourers tied to the Manor and the land……in effect “slaves”. If we are talking slavery we need to address the Ruling Class since 1066 .”

Andthe disgraceful enclosures, where people were thrown off land their families had farmed for generations, sometimes to face a choice between stealing and starving.

Well, your/my ancestors likely were surfs (a form of slavery) or pre-Norman Conquest actual slaves of other Saxons.

Blqcks think they’ve cornered the market in having ancestors who were slaves. And of course many of their African ancestors were slaves to other Africans in Africa.

Serfs! Damned spell-checker.

I’ve often wondered about education. Earth 2022, no slavery anywhere, as far as I can see. (Sarcasm).

I feel DS has somewhat lost it’s way lately, and duff articles like this don’t really help.

If you want to do slavery how about investigating countries where it’s happening to people right now? Or would that be too uncomfortable as the perpetrators aren’t white westerners?

Slavery continues to this day in the fields of East Anglia and Lincolnshire.

There is the possibility that this article is designed to make people realise how lucky they are that they have not been crammed into ships for a bumpy ride across the Atlantic eating slops and drinking their own urine, and that they should appreciate the freedoms they have and they shouldn’t criticise the Government too much.

“Look – others have it worse – stop complaining!”

And the sweatshops of Leicester East, ruled by the criminal Claudia Webb.

And still it goes on.

I doubt that the article has been designed to do that at all. It’s just a response to attempts by the race obsessed left to guilt trip white people for something they haven’t done.

Anyone with even a tenuous grasp on history who doesn’t realise how comparatively lucky we’ve been over the last 50 or so years is a bit slow.

Unfortunately, most are now firmly in the ‘don’t know what we have ’til it’s gone’ camp and are blithely munching away in the pasture.

100% correct.

I had hoped that my children would have an even better life than me, looking unlikely now.

Is it supposed to be evidence of ‘balance” – if so why bother when the rest of the Media and all Social Media is just pure Leftist Globalist Woke propaganda?

Neither, because WE did neither.

At most we can remember it and learn something from it if we like.

Proud that we stamped it out, it was going on a lot longer before we got involved and most likely would have continued if we hadn’t pushed to end it. Question, why the vendetta against British History, and not against other countries who in more recent times have caused world wars

I’m not sure what slavery has to do with discussions on lockdowns/Covid restrictions. It’s a bit like “Ooh, look! Ukraine!” .. now it’s “Ooh, look! Slavery!”

How about comparing BMWs to Mercedes, or discussing the Israel-Palestine conflict? Or the takeover of Cadbury’s chocolate by Kraft/Mondelez? Or was it wrong of the Romans to invade Britain?

Anyway, haven’t we done slavery before? The same old arguments and views to be wheeled out yet again. I thought we were in some kind of crisis where our freedoms had been seriously curtailed by The Covid Show and that dealing with that was of the utmost importance. But now it’s musing about slavery, which happened many years ago (of the Africa to America via Bristol type). I think the general conclusion is that “slavery is bad”.

Next: Were The Moon Landings Faked? Discuss.

Surely it’s time for a piece Madeleine McCann?

Long overdue I would say!

Were the Russians inolved?

Only in knowing who was involved so they could blackmail British and EU officials to ‘do their bidding’?!

This site was renamed “Daily Sceptic” from “Lockdown Sceptics” a while ago, for reasons set out by the site owner, that seemed coherent to me.

The argument that the corona madness is connected to other trends in thinking is pretty strong, so IMO all of these issues are up for discussion.

If people believe that this site has lost ts way they are free not to visit. However I am with you all the way J.

Yes indeed ! It is vitally important to see that they are all linked and being staged in sequence -against the background of the the constant agitation destabilising ‘psyop’ stress-maker recommended by Sage.

This is a long planned progressive ” Take Down” of the West its way of life its economy and and its peoples fro the sole benefit of the unholy alliance of the Extremist Deranged Left, Billionaire elites, the Globalist Banks and the Corporates- joining the dots answers all those silly “Why”? questions the sheep keep asking!

Next: Were The Moon Landings Faked? Discuss.

Yes they were.

You’re being ironic aren’t you? Please tell me you are.

After the last two years, and all the “fringe”/indie journalism I’ve been reading as a result, I no longer believe the establishment story about 9/11 and must say that it no longer sounds completely idiotic to wonder if the moon landings were real. I still just about believe they happened, but I’m no longer 100% sure.

Moon landings fake, 100 percent, no doubt about it whatsoever. The problem is all the brainwashed closed minded people who “just want a quiet life” and all the other excuses they come up with to justify their closed minded disposition. We need to have very open, very loud conversations about the fact that the Establishment is running the world on lies. We need to have large scale open source investigations into viruses, flat earth, chemtrails and climate scams, 911, 77, bankster influence, and all the other taboo subjects which they spend billions of £ ensuring these subjects NEVER get the scrutiny they deserve. Daily Sceptic is one such operation, posing as a “Sceptic”, yet in reality doing the opposite and shutting down legitimate enquiry into some of the most important issues regarding true reality.

Moon Lander Fabrication Analysis

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s6vAiyUIQog

20 Proofs NASA Faked the Moon Landings

https://www.bitchute.com/video/joNLiRUIV0M0/

Apollo Moon Lander clearly made out of paper and various other stationary grade materials

Surely it is much more important that slavery is happening today, is endemic in several countries, and needs stamping out now?

I don’t care about other countries. I care that it’s happening in the UK. The solution is to deport the slaves and make them someone else’s problem.

The Muslim rape gangs targeting white girls is just a version of modern slavery.

Mohammed the founder of that foul religion was a slaver who raped his slaves according to the Muslims own historical accounts.

Social workers in the Finnish city of Oulu have worked out how to prevent migrants from ‘other cultures’ raping Finnish girls:

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/SvIQaIgKiO4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s2Uru_vZZ8U

Checkout staff in all the supermarkets = slaves. Workers for Amazon = slaves. Face masked waiters/waitresses at the G7 meetings = slaves. Truck drivers = slaves (how do you fancy sleeping in the cab all year round with little chance of a shower, and having to pee into a bottle as there’s no time or place to stop whilst driving?).

We just don’t call them ‘slaves’ any longer and even now the Elites are planning their Smart Cities to lock them into their pods whenever the Elites feel like it.

Can’t people see that Shanghai is now the Lockdown model for the Western World? Johnson and Gates can hardly wait for their next ‘even more deadly pandemic’ to suddenly appear from nowhere to enforce it!

See how the Banks are already experimenting with their power to arbitrarily block customer transactions and their accounts to “keep people safe” – two hours to get through on the phone to challenge the decision……. which apparently was “inexplicable”!

Canada was the dry run.

Slaves don’t have a choice.

Workers for Amazon, face masked waiters/waitresses at the G7 meetings and truck drivers do.

And if their alternative is to be penniless living on the streets?

Neither – shame on those who were complicit in any slave trade. Big respect for those who fought against it. As for being responsible for the actions of one’s forbears, how ludicrous. Mine had a habit of getting in big boats and raiding places whilst chopping the odd head off.

Nobody who believes in mandatory, or even coerced, jabbing is in any position to whine about slavery.

An excellent point.

My own view is that the whole of the last two years have seen the people of the UK voluntarily enslaving themselves, or allowing others to do so. I have ventured this opinion to others, and received the expected howls of execration. The surrender of personal rights and freedoms, in exchange for servitude and oppression, cannot be described as anything else.

“Mass Psychosis” – put in place by ‘experts’ ( see S.Michie)

That evil witch has gone quiet lately. The planning meetings must have started…

Both.

But remembering every nation, every culture, every race, every colour, has some inconvenient history when it comes to slavery.

This recent trend of apologising for acts we personally didn’t commit is pure virtue signalling.

I do not feel ashamed of anything that was going on in this country in the 18th Century or at any other period of history outside my own lifetime.

I would be very interested in your arguments in support of your opinion on this country profiting from slavery

Neil didn’t say that, did he?

Not with you. What didn’t he say?

I didn’t own slaves, nor did I pick cotton, so I have absolutely no interest in that.

I do, however, feel ashamed that slavery is alive and well in Labour wards across the UK today.

Aside, I bet you didn’t know that Saint “George” was actually Turkish and his real name was Geórgios Yaxley-Lennon.

Being critical of slavery in the 18th Century, destroying statues, is about as silly as complaining about the savagery of certain dinosaurs sixty million years ago and imprisoning crocodiles for their refusal to reform.

Britain’s role, the British Empire’s role, in eradicating slavery is something of which this country can be proud; to be celebrated.

I don’t think about it as I have never owned a slave. As far as I know, historically every country used slaves, some still do. I cannot understand this need to apologise to people who aren’t slaves but whose ancestors might have been. Some people need to get a life!

I’m appalled. It would appear from your graphic that were separate ‘mens’ and ‘womens’ toilets on these ships

I demand justice for transgender slaves, we must atone for this crime

Mens? Womens?

The plural of man is men. The plural of woman is women.

Not any more

I think it was actually meant to be plural possessive, but the addition of the additional quoted identifier apostrophes made that look odd. Mens’ and womens’ toilets.

Men’s. Women’s

If you lot don’t stop I’m going to take my ignorance elsewhere

Bog off then. Do you see what I did there?

I’ll do so at my convenience

I can understand your confusion. Apostrophe’s (sic) rarely occur on toilet doors. And anyway my comment was to TBP going all poncy over plural possessives and still getting it wrong.

‘Plural possessive’ is a hate crime please stop

I await my suspended prison sentence in the post.

Hanging has been abolished.

I hang my shirts.

In 200 years’ time, politically correct historians will be exclaiming in horror at the brutal treatment imposed on the victims of lockdown, everywhere. It would be nice to think that the UK might go down as one of the first countries to put a permanent stop to lockdown bestiality. One can always hope.

In 200 years time we will have been replaced by people who do not produce historians. See South Africa and Zimbabwe for details.

Acid Reflux Nighmare: Eddie’s drink-induced anxiety dream about being stranded on a desert island with the other cast members, where all his insecurities and inadequacies come to the fore and Bill turns out to be the better man in almost every respect.

If any of us are left.

That’s all alright then, all is forgiven as all the other Europeans where doing it too.

I guess it’s alright for china, Putin and other wrongs too.

Everyone who buys products Made in China is supporting Slavery. Discuss.

Everything is made in China apart from Wedgewood ceramics, which, ironically, are made in Indonesia.

They are also being ripped off with tawdry junk, that lasts a few months and are helping to destroy what is left of home based manufacturing so making us totally dependent on an oppressive, tyrannical Communist system, that ultimately wishes to reproduce itself here – with it seems the aid of our own Elites- and will do nothing but harm.

Bollox. The computer you’re tapping out your messages on is a precision instrument probably made in China.

Had we competed with the Chinese in manufacturing we would be paying Chinese wages now.

Thatcher recognised this and turned the UK into a service providing country, the intellectual and financial high end of of the world. Whatever is manufactured, stored, transported, traded etc. requires finance, legal support, administration etc.

When did you ever meet a poor banker, lawyer or trader?

It’s an interesting thought the British ships so nobly engaged in the battle to stop slavery were themselves manned by people who had often been pressed from English coastal villages and towns, and they endured the harshest of conditions – often for years on end. Slaves in all but name.

Historians estimate that only approx 2% of the British population had any involvement in the slave trade, even at its height.

The reason for the transport of human beings to the Americas was the labour shortage there. People were needed to work the plantations, which were owned by immensely rich landowners growing crops like sugar and cotton. In addition in America, (not Britain) individuals could own slaves.

There was no need for slavery in Britain as the native British population provided an ample supply of impoverished cheap labour. If they committed a minor offence, such as stealing food, they were themselves transported as indentured labourers, or hanged.

There was little difference in the status of a British worker and a slave. This is why the propertied classes outlawed slavery in Britain in the eighteenth century. There was no economic need for it.

British merchants were a significant force behind the Atlantic slave trade between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries,[1] but no legislation was ever passed in England that legalised slavery. In the Somerset case of 1772, Lord Mansfield ruled that, as slavery was not recognised by English law, James Somerset, a slave who had been brought to England and then escaped, could not be forcibly sent to Jamaica for sale, and he was set free.

The truths behind slavery as an institution are all economic. They are not primarily based on race or colour. Attempting to pretend they are is a distortion of history and part of the current psyop, by the rentier class, to blame the impoverished UK poor for their own crimes. In fact the financiers are carrying out an attack on the UK populations economic and labour rights to remove the achievements of the last hundred years and reduce us again to a form of slavery.

This is why the narrative is is such a lie and the blame so misdirected. Our rulers want to undermine the solidarity of the population as part of the current attack on our freedoms, finances, and rights. They want to engender racial hatred here in order to cause social disorder and mistrust so that we will be unable to resist them

As far as historic slavery is concerned I am proud to belong to the country that ended the 18th 19th century slave trade. British history is not the history of the US. The current narrative is trying to confuse the two.In the US many relatively poor individuals in the population owned slaves. That never happened here, for the reasons outlined above.

The ancient egyptians did not use slave labour to build the pyramids, which were built by village labourers and specialists. Check out John Romer.

Yes Kate, the ‘Somerset Case’ is justly famous – both for the outcome, and for Lord Mansfield’s words; but the legal status of slaves and slavery in Britain had been tried and debated for a long, long time before that.

The question of human bondage, serfdom, slavery, vassalage, villeinage call it what you will, was both a philosophical and a legal matter. By late into the second half of the eighteenth century, the common law – the system of precedents set by real case judgements – had swung back and forth on the issue like a pendulum.

The critical base authority was the writ of habeas corpus which originated from the Assize of Clarendon in 1166, during the reign of Henry II. In 1215, the monarch was made to acknowledge this – and more – in Magna Carta (Article 39 on liberty).

At the Star Chamber trial of John Lilburne in 1637, Cartwright’s Case of 1569 was quoted; ‘…one Cartwright brought a slave from Russia, and would scourge him, for which he was questioned; and it was resolved that England was too pure an Air for Slaves to breathe in.’

In the cases of Chamberlain v. Harvey in 1696, Smith vs. Brown and Cooper in 1701 and in Smith vs. Gould in 1706, Lord Chief Justice Holt ruled that there could not be an action of trover (compensation) in respect of a black slave, because the common law did not recognise black people as different to white people, and that even though blacks could be bought and sold as chattels in Barbados, this was not the case in England. In the 1701 case Holt said, “….as soon as a negro comes into England, he becomes free, one may be a villein in England but not a slave…”.

In 1750, Baron Thompson in Galway v. Cadee followed Lord Chief Justice Holt in stating that a slave became free upon arrival in England. In 1762, in Shanley vs. Harvey, Lord Chancellor Henley declared that as soon as a man sets foot on English ground he is free. He asserted that a black person could take his master to court for cruel treatment, and that habeas corpus could be granted if his liberty was restrained.

In 1765, William Blackstone’s four-volume magnus opus Commentaries on the Laws of England was published, and it contained the view that, “The law of England acts upon general and extensive principles: it gives liberty, rightly understood, that is, protection, to a Jew, a Turk, or a heathen, as well as to those who profess the true religion of Christ.”

Blackstone went even further and in fact railed against slavery, proclaiming it unnatural in England;

“…..I have formerly observed that pure and proper slavery does not, nay, cannot, subsist in England: such, I mean, whereby an absolute and unlimited power is given to the master over the life and fortune of the slave..…indeed it is repugnant to reason, and the principles of natural law, that such a state should subsist anywhere.

The three origins of the right of slavery assigned by Justinian are all of them built upon false foundations…..

….Upon these principles the law of England abhors, and will not endure the existence of slavery within this nation;…….so that when an attempt was made to introduce it, by statute 1 Edw. VI. c. 3 [Vagabonds Act 1547], which ordained, that all idle vagabonds should be made slaves, and fed upon bread and water, or small drink, and refuse meat; should wear a ring of iron round their necks, arms, or legs; and should be compelled, by beating, chaining, or otherwise, to perform the work assigned them, were it never so vile;…the spirit of the nation could not brook this condition, even in the most abandoned rogues; and therefore this statute was repealed in two years afterwards.

And now it is laid down, that a slave or negro, the instant he lands in England, becomes a free man; that is, the law will protect him in the enjoyment of his person, and his property

It might be noted too that Blackstone also criticised plantation owners in his Commentaries, for, “…..their infamous and unchristian practice of denying baptism to negro servants, lest they should thereby gain their liberty…”. He was not a judge until 1770, so his commentary was not legal authority, but it illustrates the line of thinking prevalent at the time.

Britain has long stood for individual liberty – and indeed applied these principles to all races for at least 300yrs.

I can’t think that this was the case in any other country in the world.

Great post, thanks

Indeed.

That’s one of the most informative pieces on this subject and its position in English Law that I’ve read. It’s a shame that those ignorant and uninformed tub-thumpers and others that rail on about slavery do not acquaint themselves with these facts.

Anybody heard of Sarah Forbes Bonetta?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sara_Forbes_Bonetta

She was rescued by an anti slaving ship in 1850. She was destined to be killed as a human sacrifice by her African captor. Subsequently adopted by Queen Victoria and educated and brought up in the royal family.

In July 1850, Captain Frederick E. Forbes of the Royal Navy arrived to West Africa on a British diplomatic mission, where he unsuccessfully attempted to negotiate with King Ghezo to end Dahomey’s participation in the Atlantic slave trade.[7] As was customary, Captain Forbes and King Ghezo exchanged gifts with each other. King Ghezo offered Forbes a footstool, rich country cloth, a keg of rum, ten heads of cowry shells, and a caboceers stool.[8] King Ghezo also offered him Aina, who was intended to be a gift for Queen Victoria. Forbes estimated that Aina was enslaved by King Ghezo for two years. Although her actual ancestry is unknown,[9] Forbes came to the conclusion that Aina was likely to have come from a high status background since she had not been sold to European slave traders.[8] Describing Aina in his journal, he wrote: “one of the captives of this dreadful slave-hunt was this interesting girl. It is usual to reserve the best born for the high behests of royalty and the immolation on the tombs of the deceased nobility…

Dahomey was notorious for mass executing its captives in spectacular human sacrifice rituals as part of the Annual Customs of Dahomey. Forbes was aware of Aina’s potential deadly fate in Dahomey, and as he wrote in his journal, refusing Aina “would have been to have signed her death-warrant, which probably would have been carried into execution forthwith.

Captain Forbes accepted Aina on behalf of Queen Victoria and embarked on his journey back to Britain.

Some of the slaves shipped to the American Colonies (up to 1776) were (white) British & Irish transported into indentured servitude (a form of slavery) instead of being hanged or sent to gaol.

Some of those indentures were bought by black people – not every Black there was a slave.

Terrific comment.

I am of he opinion that we should pay compensation

However in the interests of fairness that compensation should be commensurate with the wealth of our ancestors

I have trawled through our family records and discovered that during the relevant period our family owned a total of four turnips

In a spirit of reconciliation I am prepared to donate three turnips

Good to have a balanced view., However, I believe we are collectively also owed a bob or two for the treatment of our ancestors by the Roman, Danes, Normans and out own ruling classes.

From tracing my ancestry back to the 1500s (before the slave trade) I am confident of almost constant serfdom, with not a shred of slave ownership. Mea definitely not culpa.

Four turnips. Lucky lucky berstards. I gather that mine only had four pebbles. However the blessing of that was that pebbles lasted a lot longer and you could suck on a pebble all day.

My ancestors wealth consisted of a bucket full of shit.

Can you guess how much I’m willing to give up.

Certainly not the bucket, I hope.

And we should claim back rent on the Caribbean islands which we gave away; and a contribution to the costs of the Royal Navy operations.

I strongly suspect that many of my ancestors were serfs …. little better than slaves. So I’m a bit conflicted …… should I be furious that they were effectively owned by the local Lord, or proud that the English ended serfdom long before many other countries (ie Russia, where it continued until the early 20th century)?

Oh …. and who’s going to pay ME reparations for my ancestors’ serfdom? Which is what the BLM campaign about the transatlantic slave trade is really about.

The Black Death effectively ended serfdom in practice, but Elizabeth I banned it officially.

Anyone, anywhere, living today is responsible for their own actions. Nobody knows what sufferings they caused before this life, neither do they know what sufferings they experienced.

If anyone is foolish enough to adopt a feeling of pride or injustice based on arbitrary association with people in history, then their actions in this life will be hampered by attachment.

As a counterargument against the obsession with a past we cannot change, what about a discussion about a future we can? Our cultural enemies are not the most rational of people but, with the climate agenda, they have introduced the notion of modelling as a reasonable way to establish current policy. So let’s model something much more useful, namely demographics.

By 2100 white Europeans will be a tiny minority of the world population, which is what drives much of this clamouring for revenge, the idea we are now weaker and can be pushed around.

One simple projection sums it up; in 1950 there were about two Europeans for each subsaharan African. By 2100 there will be seven Africans for each European.

In the richest traditions of the woke brigade here are my predictions if this happens.

I’m not making a case for or against. But I find it hilarious we are a target for such ire by minorities, feminists and gays, all of whom are in for a tough time if we decline in the ways they are helping encourage.

As far as I can see, in the UK, and much of the western world, we are all slaves anyway. The appalling physical conditions may be ameliorated, but not the basic relationship between us and the people who think they own us.

I am not allowed to work without permission of the state, therefore cannot feed and house my family without permission of the state. NI number. 40 years ago you could do cash in hand jobs, like work in a pub, cleaning etc with no problems. Loads of women did that sort of job, while the kids were at school. I suspect the minimal loss of tax revenue was far less than the cost of benefits and without the administration overhead.

I pay a tithe of my labour, two and a half days per week at least, to the state.

I am not allowed to work unless I can produce state issued documents. Passport, proof of address, …

I am not allowed to purchase a property without state permission. Passport, driving license….

If I wish to purchase a property, and am allowed to do so, I must pay a tithe of my past and future labour to the state. Stamp duty land registration etc.

I cannot receive payment unless I can prove I have state permission to do so. Have you tried opening a bank account recently?

I am not allowed to rent my property to another, without the permission of the state. Scotland landlord registration.

I am not allowed to leave or enter the country, without the permission of the state.

Most of the above, to the degree where it becomes soul and life sapping, has happened in the last 20 years.

Students are forced to pay a tithe of their future labour to acquire a basic education. As far as I can see, the modern degree is equivalent to the A level standard of the 1950s, 60s, 70s.

The lines between between citizenry, forced labour and slavery are blurred. Just because you have central heating and a bed doesn’t mean you aren’t a slave.

Great post! And yes it is profoundly “soul sapping”!

The central heating will be but a fond memory soon enough.

Rocket mass heaters.

Slavery is already back with the new P&O workers earning £2.50/hour.

Expect the P&O boycott to last as long as the Tesco’s boycott.

Slavery could return as early as 2024. If we sign up to this Pandemic treaty being pushed by the WHO, an organisation of no legitimacy whatsoever, and then adopt mandatory vaccination, the population is effectively a slave population.

By definition slaves do not own their bodies.

Only if current population continues. Worryingly, countries with sensible birth rates (above replacement level) may go the way of most of Europe

It is extraordinary that so many people appear to be totally incapable of understanding that the people who lived 200+ years ago are not the same people who are alive today.

Prove it

You mean in the olden days? That’s about the level we are at.

On a psychological level it is projection. A well understood phenomenon. Despite 50+ years pouring money into poor parts of the world some groups just aren’t keeping up.

When your identity is partly based on the equality racket how can you explain global inequalities? You must keep the past alive and remind us we are privileged.

Be proud or ashamed of one’s own actions: fair enough. But to be proud or ashamed of other’s actions decades ago (or even nowadays) is frankly daft.

Will we be called ‘slaves’ to the WHO in 2023 when countries sign up to their Global medical intervention Plans

I was neither involved in the slave trade nor did I have anything to do with stamping it out and I very much suspect that applies to everyone who comments on here.

With your white supremacist name how can you say this? We are all guilty.

Look I’m just a troll slayer and dragon killer, have spear, will travel and all that.

The wokists tell that all cultures are equal and must be respected, none is better than any other (they do this whilst denouncing anything to do with white British people and our culture).

When those early European travellers went to Africa seeking to trade they found African rulers who wanted to pay with slaves.

Now surely accepting those slaves and using those slaves for their intended purpose was in accordance with wokist ideology.

For the Europeans to denounce the African cultural practice of slavery would have been an act of cultural spremacy and the woke have taught us that this is high crime.

lol

My Sussex ancestors, impoverished farm workers, were slaves by any other name, tied home and then homeless and the workhouse when they died

I am white and British (just think, sixty years ago I wouldn’t have needed to use the word white to explain what I am everyone would have known that being British meant you were white).

Apparently I am responsible for absolutely everything that any white British person has done that is considered to be negative but I am not to be credited with anything that any British person did that was positive.

Funny old world innit?

When we are told to look at the trans Atlantic (is the Atlantic unsure of its sex) slave trade no one seems to ask a few fairly obvious questions.

1) What would have happened to these slaves if they were not shipped to South America or North America?

Would they have lived lives of freedom, peace and harmony or would they have been kept as slaves in Africa or sold to the Muslims who would cut the nuts off of the men and killed the offspring of any of the women they raped?

2) You only have to read The Road to Wigan Pier by George Orwell to understand that life for many of the regular British people was no better than the life of a slave even as late as the 1930s. To present things as if all whites lived lives of luxury whilst all blacks lived lives of misery is simply cobblers.

Spare a thought for the Aussies. Transported for stealing sheep dung and then elevated to the status of slaves in 2021

That image is one of the earliest and most successful pieces of visual propaganda in history. It played a major role in the abolition debate.

In particular, it shocked people into rejecting ridiculous claims by traders about cruise-like conditions on the journey, with regular dancing, craft classes and delicious dinners for the captives.

Technically it is propaganda, but its power lay in the fact that it was totally accurate. The artist went to Bristol to measure up a specific slave ship (the Brooks). The layout of slave berths was exactly as specified by the ship owner.

A shame he didn’t paint images of white slaves taken by Arab and African slavers. It might at least have presented a sense of balance.

Never mind that there are plenty of historic images.

Interestingly, the only people I have ever heard discussing the subject are white and middle class. The Africans I know just aren’t interested

Can confirm this from my own experience. I’d go further. Some Africans and Indian immigrants I know are grateful for what we provide now, a peaceful society that doesn’t treat them as inferiors.

Interestingly some of the Africans I’ve discussed it with are very aware they are economic migrants and are baffled at the obsession with race and culture. They have no illusions as to why they are here, for the economic benefits we can provide. They too note it is bored white people not minorities pushing this.

Some are even growing wary of the clamour from BLM types, especially Asians, as they feel it is drawing unwanted attention and may trigger a backlash.

Much of this is quite deliberate.

I believe Soros stated he would divide America along racial lines.

Yes I agree. It is a natural fault line history warns us about. The current conflict in the East is between two groups of Slavs/Europeans. So even culture causes problems as we saw in Northern Ireland.

It is destined to fail as one dominant culture always emerges and either dominates or destroys the rest. Anglo-Saxons or the Han, for example.

Taking into consideration –

The value of the technological improvements that were taken to Africa by Europeans

the £tens of billions given in food aid to Africa

the £tens of billions given in medical aid to Africa

the £tens of billions given in disaster relief to Africa

The £billions spent in welfare payments, free education, health care etc for those that are in the Western world

The cost of the repairs after their race riots

The criminal justice costs from picking up after all their crimes

I have concluded that on balance they owe each white person £50 000.

Surely the good Dr. has registered by now that, in the age of woke, any attempts at context are merely another part of the problem.

The criminal enterprise BLM allow no context. The white, middle class, interfering, curtain twitching do gooders also enjoy their hair shirts.

There is a whiff of puritanism tying it all together I think. Let’s punish ourselves for the sins of our fathers.

Not only did it cost Britain £squillions in treasure to crush the slave trade, it also cost the RN thousands of lives lost to tropical disease.

“Beware, beware the Bight of Benin,

Only few come out where many went in”.

The most successful anti slaving ship was “The Black Joke” which was nothing to do with race, but referred to a bit of female anatomy.

A great little historical factoid is the reports of British and American captains on freeing slaves. Many remarked how indifferent the freed Africans were when returned to their homelands.

We pretend people yearn for freedom, but most just want a more benevolent master.

Yes, although it was extremely rare for them to be returned to their own village or district (for practical reasons). So their life was not going to be straightforward.

1568 able seamen.

We neither should nor can feel genuine shame for what anyone else does, only for our own harmful actions (and even then only until we feel remorse and stop doing whatever it is, the whole point of having a conscience).

The sheer ludicrousness of the concept of feeling shame (or indeed pride) for the behaviour of long dead human beings who just happened to live in the same artificially sectioned off geographical area as us is one of the best ways of highlighting the nonsense that is nationalism.

That does not, of course, mean that we cannot either condemn or praise others’ ideas and actions (including historically), simply not ascribe them to ourselves.

At a more practical level I agree with comments below that any discussions about slavery should overwhelmingly be focussed on the abolition of its contemporary manifestations (although historical investigations are interesting and valuable).

You know when you read something and you belly laugh, a laugh that you just can’t stop?

I read this back in 2017 –

Migrants from west Africa being ‘sold in Libyan slave markets’https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/10/libya-public-slave-auctions-un-migration

So it turns out that Obama, the brown Messiah, in bombing the snot out of Libya and destroying Gaddafi had resulted in the return of open slave trading.

The evil white man put a stop to it only for the brown Messiah to bring it back, the irony is simply dripping everywhere.

I agree to paying compensation but only if it consists of a one way ticket back to the paradise that is Wakanda.

To be fair the brown people pack themselves more tightly onto a rubber dinghy to cross the channel so perhaps being ram packed into boats is just a thing they like doing?

As undocumented illegal immigrants they will probably end up working as slaves in Asian owned garment sweatshops in Leicester or in other foreign owned businesses, so are you a slave if you decide to be one?

Leicester: Up to 10,000 could be victims of modern slavery in textile factorieshttps://news.sky.com/story/leicester-up-to-10-000-could-be-victims-of-modern-slavery-in-textile-factories-12027289

Slavery has been around since before recorded history, we are not responsible for slavery but we did lead the world to get rid of slavery.

A total waste of money.

Why, as far as I’m aware every civilisation in history was or has been involved in slavery at some time. African chiefs sold their own people into slavery for profit. As far as I’m aware there were 3 main African slave trades, internal, Arabic and Western. If I was a slave I’d be grateful I was sold into the Western market. The internal market, slaves were cheap and expendable. The Arab market slaves were cheapish, the males were castrated before being force marched to be sold. About 1/3 died from the castration process and another 1/3 died on route. Children were killed as they had no economic value. Women had to abandon their child as they also had to carry goods and couldn’t carry goods or a child. The western slave market the slaves were expensive and needed caring and looking after. (In many instances slaves got better treatment than “free” poor).

The blacks now who are complaining about their ancestors being slaves. Where are the descendants from the internal and Arab slave trades, there aren’t any as they didn’t have any. At least slaves in the western trade had descendants.

Interesting to ponder, also, whether you would prefer to be a Haitian or (say) a Barbadian?

Or a Liberian, or a Nigerian?

Or Citizen of the USA or any of the above?

If we start forking out (even more than we already have done, for generations), how long will it be before we start getting dunning letters from those whose ancestors were NOT sold by African chiefs for transportation to the New World?

I – along with many others – have made this argument for years: that the only unique things the British Empire did in regards to conquest and oppression was to end slavery and instil democracy in the countries it gave back.

In terms of conquest and bondage; we were just doing what everyone else in history did, and what was accepted as legitimate for all that time. The only reason it stopped being legitimate was due to Western European moral philosophy. There’s no doubt in my mind that the British Empire – while far from perfect to modern minds shaped by our own concepts of human rights – was overwhelmingly positive on a global level. Everything we think of as freedom, human rights, equality etc stems from European thinking catalysed by British action.

‘Everything we think of as freedom, human rights, equality etc stems from European thinking catalysed by British action.’

Which is all being rapidly eliminated by the globalist cabal.

The subsaharan slave trade was going for centuries before any European showed up.

The Arabs always cut the nuts off the African male slaves as soon as they bought them.

The Arabs always killed any children born as a result of them raping their female African slaves.

The Arabs weren’t stupid, that policy meant their future generations avoided no end of grief.

As they say on some forums, the Americans imported about 300,000 African slaves of which only 40 million of their ancestors survived. The Arabs imported over 8 million and none survived.

Don’t see BLM banging on about that

But for mass immigration and multiculturalism we wouldn’t even have to think about this shit.

Well it is driven by woke whites. So the colonial aspect, which is what they are really after, is behind all the angst.

I am against mass immigration but I can’t really blame them for this. In fact I know a few well educated Asians quite concerned about where it is all going. They know enough history to understand how crazy we can be, and they are well aware this is coming from the over educated, over socialized groups in society who don’t represent the majority.

I think they are right. This will cause a backlash and that is maybe no bad thing.

I think we have had enough of this constant Guilt Trip psyop being politically mounted against the West by those who seek to destroy it.

Every single human being involved in the transatlantic slave trade has been dead for over a hundred years. This country abolished it as an abomination earlier than all others. This achievement was written around the iron legs of the Britannia tables used in all British pubs!

Meanwhile, the ‘Modern Slavery’ involving all races – especially from Africa and Asia to the Middle East -continues – as does so we hear the sex trafficking from the Ukraine…… as does the large scale child sex trafficking no-one even wants to talk about.

The UK had largely dealt with any racial problems we had in the country by the 2000’s. There were unpleasant individuals who were bigots, sadly that will never be eliminated, but for the most part, It was all but done and dusted.

Problems emerged from the huge number of, predominantly, black children who didn’t/don’t know what a father or a family unit is. Denzel Washington is outspoken about this as the underlying problem amongst black communities.

The children, especially males, are left to their own devices as their mother is forced to be the sole provider for her children. They end up on the streets and perpetrate a disproportionately high level of crime compared to their ‘white’ counterparts who are more likely to function within a family unit (nuclear family).

They get pursued and prosecuted by the police, then the accusation of racial profiling is levelled however, fortunately or otherwise, the colour of ones skin is a significant identifying feature of a crime participant. As the very least it eliminates 90% of the country from an investigation or, in fact, eliminates 10% of society if the perpetrators skin colour is identified as white.

Despite what we are led to believe, the police don’t just go around scooping up black people without supporting evidence like age, height, weight, clothing, fingerprints etc. No point in interviewing a 6’4″, 42 year old black guy when the perpetrator is described as a 5’6″, 14 year old black child.

A great deal of contemporary racial tension can be traced directly back to the MET and the Stephen Lawrence case, which they bungled, and thought it would be better to admit to racial bias than the real problem, systemic incompetence.

Forgive me, but this is naive. I agree with your conclusions about the Lawrence case, as well as your observations about blacks and racial profiling.

But things have moved on. Our problems now are caused by the volume of immigrants and by a steady drum roll from wokesters about us being racist.

The Lawrence case had its effect, but will be remembered as a minor blip on the radar. The colossal demographic changes and its impact on our culture, way of life and economics dwarf the points you made. We cannot cope with the numbers we have now never mind the millions yet to come. And in case you haven’t noticed, many are not assimilating. This is even talked about by the government who are reluctant to discuss any aspect of race or immigration. If we stopped now and imported no more we would still be looking at 50 to 100 years to assimilate what we have already. Some of us are simply asking if any of this is worth it.

The ethnic groups we are bringing in famously have a strong in-group preference, a strong preference for their own kind in all walks of life. This distorts the society we have built for ourselves and, if they come in sufficient numbers, is something we will struggle to survive.

Your own observations on blacks illustrates the key point, they are not like us and do not behave like us; they are a poor fit for our society. Why spend our lives compensating for their meager contribution when we can just deport the lot?

The moment you fail to distinguish between legal and illegal immigration you have conceded the debate.

Quite apart from your final paragraph being entirely racist, where do you intend to “deport” them all to?

Send them back to France? How, precisely? Rent a ship and sail them into Calais, to be met with a gunboat? Or do you train them to jump out a plane and parachute them into a country of your choice?

Didn’t we try that sort of thing with the Windrush community?

How long did it take the UK to deport a single Imam back to Jordan, whilst he was living a lavish life here and preaching hate. Ten years? I forget now.

There does seem to be a concerted effort to rewrite history lately. I was just looking into the “Age of Enlightenment”, many of the ideas during that phase led to the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. Granted not everything aout that era was good such as the rise of dictatorial regimes. History is complicated and messy and interpreted by different people to suit their political biases.

I find that having read the article and thought about the titular question that I don’t particularly feel anything regarding the subject.

Slavery of any description is bad but I haven’t been responsible in any way for past slavery and the people of that time profiting from it. Neither do I have any connection to those who abolished it.

We should be proud we were the first to stop it and celebrate that. Back then the whole world was at it, both first, (second) and third worlds as was.

But don’t worry it’ll be back within the next 5 years if the globalist agenda succeeds and there will be no discrimination based on colour, all colours will be enslaved.

MY post is awaiting approval. Until then please see this link.

Human sacrifice in 1850s african kingdoms. Sarah Bonetta was rescued by an anti slaving ship and adopted into the royal family by queen Victoria.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sara_Forbes_Bonetta

A few years ago at the museum of Liverpool I was berated by a curator / assistant for openly telling my children that we didn’t invent slavery and recognised it was wrong so abolished it – that is not the narrative they wanted to sell.

Britain owned the ships? Not the international traders/finaciers then?

How does that even make “Britain” responsible for the trade?

‘Britain’ wasn’t/isn’t responsible for anything, it is either a geographic or political expression but in either case it has no agency.

Very few British citizens were involved in slavery; very few git rich, but that does not mean it was Government policy or popular business activity, no more than because some British citizens are engaged in illegal drug trafficking means ‘Britain’ is responsible or profiting from drugs.

And the people who made the transatlantic slave trade possible were African slave traders who captured and sold their own people to Europeans.

“It takes no more research than a trip to almost any public library or college to show the incredibly lopsided coverage of slavery in the United States or in the Western Hemisphere, as compared to the meager writings on even larger number of Africans enslaved in the Islamic countries of the Middle East and North Africa, not to mention the vast numbers of Europeans also enslaved in centuries past in the Islamic world and within Europe itself. At least a million Europeans were enslaved by North African pirates alone from 1500 to 1800, and some Europeans slaves were still being sold on the auction blocks in the Egypt, years after the Emancipation Proclamation freed blacks in the United States.”

― Thomas Sowell, Black Rednecks and White Liberals

In my opinion, it’s advisable to avoid getting dragged into this discussion. Like so many things which unfortunately spook the so-called West, it’s really nothing but US domestic politics spilling over into other countries which are more-or-less independent members of the USA-led block. To certain US politicians hunting the black vote, nothing but so-called black history matters. Self-respecting people of any skin colour ought to look down on something like this with disdain: In the end, it’s about nothing but (hopefully) fooling people with flattery and about sowing discord because one hope’s to be able to reap something from that.

Where are the trolls on this thread?

Little confused about this.

I understand that Whites are all guilty because a few of our ancestors shipped slaves to the new World.

But those slaves were typically bought in slave markets from African or Arab tribal rulers or merchants.

Does that mean that Blacks and Arabs are equally guilty? If not more so?

Saying this as an immigrant: on St. George’s day you should feel proud of all of the achievements of your fellow countrymen. Lord knows, there have been many. And strive to be worthy of their legacy. Don’t waste it. Like Tom Hanks said: “Earn this.”

I recommend a visit to the national maritime Museum in Liverpool, after which no-one could be in any doubt about the extent of Britain’s financial involvement in slavery.

If you claim to truly admire or even love your country it is necessary to expose and get to know its whole history, I expect many Britons admire and love the idea of Britain, without realizing the obvious fact that it is it is one of the greediest and most warlike nations on earth. Lying politicians today capitalize on this fact to allow them to start new wars in for example Ukraine.

Even patriotic Americans realize that it is lamentable side of Britain that they have inherited.Hence, it is sometimes said that, since world war 2, no US president has failed to start a new war. Trump might be an exception. In this country we still have much to atone for.

Did you just pass over the bit where the Royal Navy’s grossly expensive efforts to stamp out slavery is described?

Is the whole history of the UK documented in the museum, the enlightenment for example? Are the inventions and industry we exported to the world described there? The very computer screen you’re viewing this blog on is directly descended from the TV, invented by a Scot. The means of connecting it to the rest of the world was also invented by another Scot.

Is it also described there the efforts and expense Britain incurred exporting Democracy and the rule of law to lawless nations who were hundreds of years behind us culturally?

Greenwich is still used as the centre of the maritime world for timekeeping. The English language is the first language of trade across the world.

The Mongols and, Romans, amongst others, were waging continental wars long before Britain was.

Like the English language and the Democracy they so fiercely protect to the point of allowing every one of their citizens to be armed?

Wha’s Like Us – Damn Few And They’re A’ Deid

The average Englishman, in the home he calls his castle, slips into his national costume, a shabby raincoat, patented by chemist Charles Macintosh from Glasgow, Scotland. En-route to his office he strides along the English lane, surfaced by John Macadam of Ayr, Scotland.

He drives an English car fitted with tyres invented by John Boyd Dunlop of Dreghorn, Scotland, arrives at the station and boards a train, the forerunner of which was a steam engine, invented by James Watt of Greenock, Scotland. He then pours himself a cup of coffee from a thermos flask, the latter invented by Dewar, a Scotsman from Kincardine-on-Forth.

At the office he receives the mail bearing adhesive stamps invented by James Chalmers of Dundee, Scotland.

During the day he uses the telephone invented by Alexander Graham Bell, born in Edinburgh, Scotland.

At home in the evening his daughter pedals her bicycle invented by Kirkpatrick Macmillan, blacksmith of Dumfries, Scotland.

He watches the news on his television, an invention of John Logie Baird of Helensburgh, Scotland, and hears an item about the U.S. Navy, founded by John Paul Jones of Kirkbean, Scotland.

He has by now been reminded too much of Scotland and in desperation he picks up the Bible only to find that the first man mentioned in the good book is a Scot, King James VI, who authorised its translation.

Nowhere can an Englishman turn to escape the ingenuity of the Scots.

He could take to drink, but the Scots make the best in the world.

He could take a rifle and end it all but the breech-loading rifle was invented by Captain Patrick of Pitfours, Scotland.

If he escapes death, he might then find himself on an operating table injected with penicillin, which was discovered by Alexander Fleming of Darvel, Scotland, and given an anaesthetic, which was discovered by Sir James Young Simpson of Bathgate, Scotland.

Out of the anaesthetic, he would find no comfort in learning he was as safe as the Bank of England founded by William Paterson of Dumfries, Scotland.

Perhaps his only remaining hope would be to get a transfusion of guid Scottish blood which would entitle him to ask “Wha’s Like Us”.

A similar poem could doubtless be written about the English.

Ironic, isn’t it, that (so far as I can tell) every country in the world uses time zones derived from Greenwich time (i.e. whole or occasionally half or quarter hours different).

I’ve said before, in the 18th century, English people were slaves in North Africa. That’s just how things were then.

You can say it as much as you like, where’s the documentary evidence?

Let’s be clear, we wouldn’t have had to stamp it out if we hadn’t been making money from human trafficking.

There’s no choice involved, there’s one simple situation: we got rich doing something morally disgusting and then decided to become moral after having made the money.

Those that argue about this are simply saying, without saying: ‘We’re not going to pay back all the money we made trafficking slaves!’

Not really that different from what is happening in China under Mr. Xi. Only the numbers are a bit higher. Over a billion people, slaves. 26 million now locked in their apartments with no food, water, medicines for one month. Anyone in government of any country or the church of England or the Vatican or the Muslim community, Jewish community, Hindu community have any objection to this slavery? It appears not.

Point one, I don’t care, the sins of centuries ago are no longer relevent to us as individuals, no more than the Mongolians should feel ashamed for the exploits of Ghenghis Khan the real matter is no Western nation practices slavery anymore which is far more than can be said for practically the rest of the World.

The SJW’s should concentrate their shrieking at those surely?

And yes the UK was the Worlds first nation to stop doing it, shame?

Nah none.

Pride in our nation, yes.

I don’t think we’re allowed to blame the Religion Of Peace, are we?

Who still pratice slavery in North Africa.

Not for the Atlantic slave trade , no.

Is there some potential for a very tasty stream of money in this for the legal fraternity?

The Truth About England and Slavery

by Dr. Paul Jones

https://dailysceptic.org/the-truth-about-england-and-slavery/

An important and timely essay. Thank you.