The General Social Survey is a long-running survey of the US population that’s taken place every few years since the 1970s. It asks about respondents’ demographic characteristics, political views and social attitudes. One of the questions concerns happiness with one’s life. Specifically, respondents are asked:

Taken all together, how would you say things are these days—would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?

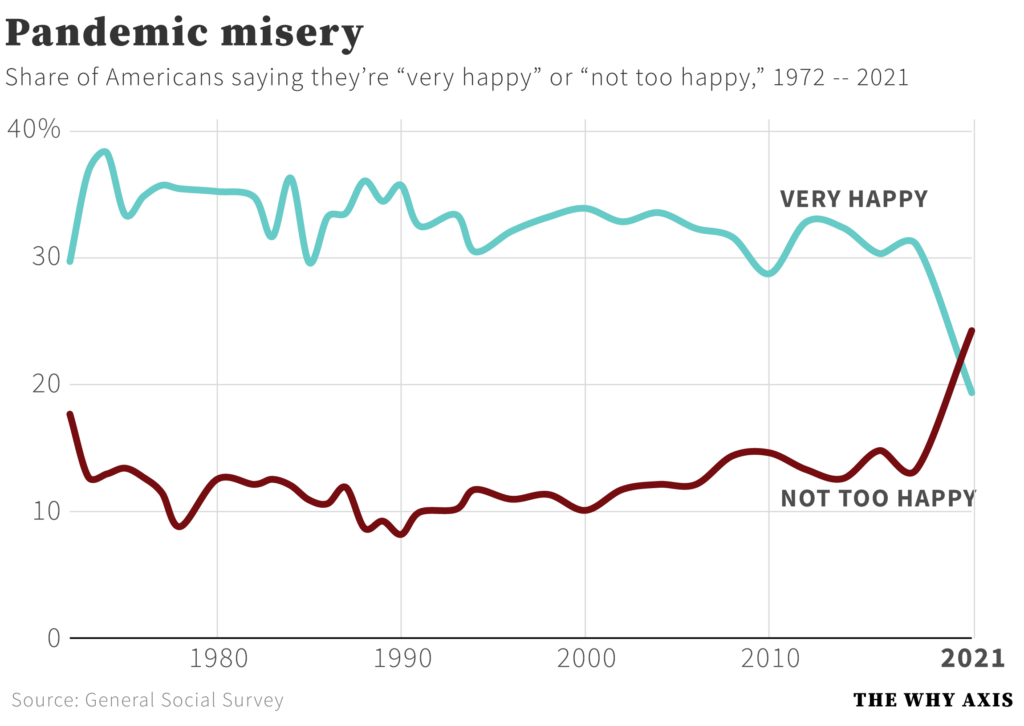

The percentage of Americans saying “not too happy” has been consistently below 20% since the question was first posed in 1972. But in the latest survey, something rather concerning happened: there was a dramatic rise in the percentage saying “not too happy” – from less than 15% in 2018 to more than 22% in 2021 (see below).

There was also a corresponding decline in the percentage saying “very happy” – from 30% to less than 20%. (The survey didn’t take place in 2019 or 2020, so we don’t have data for those years.)

Changes of this magnitude in social surveys are extremely rare, especially when it comes to questions like the one about happiness. Could they be due to some methodological issue with the General Social Survey?

This seems unlikely, as the result is backed up by a recent Gallup poll. (Both the National Opinion Research Center, which administers the General Social Survey, and Gallup are respected polling organisations.) Every year since 2001, Gallup has asked Americans:

Next, I’m going to read some aspects of life in America today. For each one, please say whether you are — very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied. How about the overall quality of life?

The percentage answering “very dissatisfied” has never been above 10%. But in 2021 it jumped to 12% – up from just 4% the previous year. Likewise, the percentage answering “very satisfied” plummeted to 20% – down from 37% the year before.

It seems that 2021 really was a miserable year for Americans. Note that, in both surveys, Americans were substantially happier in 2002 – the year following 9/11 – than they were in 2021. The Gallup survey took place just four months after the attacks, yet only 3% of respondents said they were “very dissatisfied”.

The three factors that could mostly plausibly explain 2021’s dramatic fall in happiness are: the pandemic itself; the response to the pandemic; and the upheaval surrounding the death of George Floyd.

Disentangling these three factors is obviously not easy. However, there’s good reason to believe that the pandemic itself – by which I mean the illness and loss of life caused by Covid – can’t explain such a sudden shift in happiness. Why not?

Well, we know that the fall in life expectancy in the U.S. in 2020 was ‘only’ about 1.8 years, and part of that fall was due to the massive increase in homicide. Now, 1.8 years sounds big, and it is a large year-on-year change. But it only takes the country back 18 years in terms of rising life expectancy.

In other words, U.S. life expectancy was lower in 2001, 2000, 1999 and every year before that. Yet, as we can see in the chart above, happiness was substantially higher back then. In fact, it was substantially higher in the 1970s – when life expectancy was up to six years lower than in 2020.

This suggests that the response to the pandemic – including lockdowns, mandates and the spreading of fear by the media – is a more plausible explanation for the drop in happiness than the pandemic itself. Of course, the total amount of illness and death probably would have been higher in the absence of this response, but I’d argue not much higher.

As noted, disentangling the three factors is challenging, and without additional data it’s difficult to say whether the response to the pandemic, or the social upheaval surrounding the death of George Floyd, mattered more. But it’s possible that lockdowns and other restrictions caused the biggest drop in American happiness since surveys began.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Aren’t Budweiser sponsoring this geezer as well.

Sort of ironic, fake beer for a fake women.

Geezer, Yes!

Not bowing to the thought police.

Nor am I.

Kid Rock perhaps says it for us?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JZ19c16nZOQ

Plus I think Candace Owens nails it…!

Apparently they lost $800 million of market cap value as their shares nose-dived.

Nike. Me no likey.

Really like what Jessica Rose has to say on what the definition of a woman is and the whole trans ideology thing coming at us from all angles;

”I want to now transiently examine the ‘transgender movement’ (‘activists’) and the way in which, well, the movement (not to be confused with individuals) is pretty much being shoved in our faces and down our throats at every turn lately – and not just on social media. This ‘movement’ is appearing in public settings and even more disturbing to me, in strange and inappropriate settings that are aimed at children. I am seeing a lot of irrational violence associated with these so-called activists, as well.

These ‘movements’, among many things, are tricks – imposed propaganda-style – to try to convince you that we’re all separate, different and in a big stupid constant fight. We’re not. Don’t fall for it. War gamers are devious. And their pawns are clueless. See them for what they are. Many of the victims of these tricks are the young. They need good role models and good guidance. Away from predators. It’s always been like this. Be a good role model.

Ultimately my philosophy is this, do what you want, but don’t shove it in my face and tell me I have to like it or even put up with it. Especially if you’re preying on children. I have fought bullshit my entire life and I am not stopping now. I am woman. Hear me roar. And as much as many people would like to pretend that there are no lines to cross: THERE ARE.

So what is a woman? I am a woman: an adult female human being carrying two X chromosomes.”

https://jessicar.substack.com/p/i-can-define-what-a-woman-is

At a school recently, someone gave a talk about freedom of speech and gave as an example of freedom of speech the freedom from coercion to call people by chosen pronouns. In other words, freedom of speech entailed not being forced to use a pronoun just because someone demanded it.

The reaction afterwards:, on the whole, the boys thought it.made.perfext sense and the girls were appalled and thought the speaker was a transphobe.

There is something that those who want to make this an assault on women are missing and that is that this ideology is most appealing now to teenaged girls.

Until that is paid attention to, understood why and addressed the problem is just going to get worse.

I think you make a very good point. Perhaps the girls’ interest and support is linked to a reaction to the girly girl porn style which was offered to little girls until quite recently (all clothes pink and purple, glitter and stars for toys) and a return to a sort of tom boy option that many of us leaned towards when we were growing up (think Famous Five – George was one type of girl and Ann another). If you want to hide your sexuality at school and not be the object of boys unwanted attention then perhaps now young girls choose to hide behind the trans idea.

Watching France 24 recently when abroad I was very intrigued to see that in a piece about Drag in France they also interviewed a Drag King – woman with painted on black moustache – who made the point that this is just/still the patriarchy in a new version which women are not allowed to object to because it is “unfair”. A very valid observation.

That’s a very fair point. I agree over sexualisation of women and young girls in particular is very corrosive.

I would just point out that much of the pressure on women comes from other women. At least that is what I’ve heard many say.

The advertising and entertainment industry doesn’t help at all obviously. It’s a bad cocktail.

Not surprising. Wimmin have been forcing down our throats their World view of their eternal fight against the Patriarchy, toxic masculinity, I’m a Ms not a Miss, women and men are equal – but not in sport apparently – women should have access to men’s spaces, but woman should have spaces reserved just for them.

It’s natural that the little, maids would identify with fellow victims.

“Movement” used to refer to bowels.

And the product.

Just read this … excellent and beautifully written … thanks for the pointer.

This is really a come to Jesus moment for feminism.

After decades of flirting with the notion that the differences in behaviour and outcomes between men and women are not biological but socially constructed, the idea has gone half a step further and spawned an ideology in which gender is a social construct. Men can chose to be women at any time and vice versa. Why not, they’re basically the same, right?

Feminism has spun out of control and we now have a new ideology, even more hateful, destructive and insane.

How to get the cat back in the bag.

I’m pretty sure that more feminist self victimisation is not the answer. Men, especially young boys being bludgeoned with this ideology in schools, are equally being assaulted by this madness.

Sorry, are we reading the same thing? Sharon Davies, who I suspect considers herself to be a feminist and standing in defence of the integrity of actual women…..is the one asking people to boycott Nike…

Dylan Mulvaney is a man..the President and CEO of Nike is a man …the eight most senior executives behind him are men.

Dylan Mulvaney also advertises Bud Light…. The president and CEO of Anheuser Busch is a man….there are 15 executives in the ‘Leadership Team’…14 of them are men….….…..

…….and femenists have a problem?

As usual I don’t recognise any women I know as the type of ‘feminists’ you always describe…..Where the hell do you meet these women?

So men bad, woman good? Gotcha.

Ebygum was simply stating the facts about who is making decisions in those companies. Your response seems to say more about where you are coming from than anything else.

Point …missed..whoosh!!

Yes and I’ve given examples of women driving this too.

It’s complex.

Large corporations are adopting climate nonsense and the whole woke agenda for very devious reasons. They are forming a coalition with their biggest traditional enemy, the far left, who would normally be after them for being capitalists, but because then left is now all about climate change and wokism, they’ve become allies.

So companies can continue to make enormous profits and expand their power with the support of the left, as.long as they play the woke game.

Some feminists like Sturgeon or those crazy Kansas women law makers are pro-trans agenda. Others, like Rowling, are against.

And that is basically like Sunni vs Shia or Catholics vs Protestants. The trans agenda is basically the radicalisation of the feminist agenda.

That’s how I see it. And that would explain how teenage girls are so for trans rights, why teachers unions are for trans rights, why the teaching profession as a whole, so dominated by women, is allowing its.proliferation in schools and how radical feminists like Sturgeon are for it too.

The problem of trans ideology needs to be understood properly, not superficially, from news headlines.

I don’t consider Sturgeon to be a feminist of any sort … she’s an awful person, in every way, and just clearly following the nutty agenda..you seem to think all women are feminists, particularly the bad ones. They aren’t….

it’s just a label you smear most women with…as in your other post you think women are to blame for the notion that “the differences in behaviour and outcomes between men and women are not biological but socially constructed”…good one, except which women are these, as I don’t know any that would agree with that sentence?

And as it’s men..being trans-women, who are making all the fuss, and expecting the rules to be changed for them???

There are as many men involved in this as women, so what are we going to call them..radical misogynists? Every time these stories crop up shall we just blame it on the radical misogynists?…it is after-all about trans women..who are biologically male….not the other way around..

Yes it’s a big subject, yes it’s more complex, but the issue in this report is that trans-men are being ‘favoured’ over actual women…

…trans-women are infiltrating women’s spaces, which means women can’t feel safe in jails, hospitals or any ‘shared space’….trans women are invading women’s sport…Fallon Fox, the MMA fighter, and a trans-woman, has just fractured the skull of a second female opponent…..and while it might be a side show to you, it’s very real to the women involved…

You’ll notice I don’t bring up women or feminism in any other context other than the trans problem. So, no, despite your insistence I am not a misogynist. It’s simply that current trans ideology has its origins in feminism and I’m calling it out, not to have a go at women or any nonsense like that but because I want the problem solved.

Just because you don’t consider Sturgeon a feminist doesn’t mean she isn’t. She thinks she is and says so. Just because you don’t recognise the feminism I describe it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist and it doesn’t mean it doesn’t have enormous influence on the social discourse. It does exist and the influence of more extreme feminist views is clear.

How many people believe in extreme gender ideology, male or female? Few. And yet there you have the results affecting our society very profoundly. With organisation, influence, funding, powerful allies and zeal few people can accomplish a lot.

I’ll repeat, having to make this point over and over again is like trying to get the idea of “safe and effective” out of the mind of someone who thinks modern medicine is one of humanity’s greatest achievements and that our medical establishment would never do that to us.

I have never said you are misogynist..just asking why women you think are guilty have a name and the men don’t?

I don’t agree that trans ideology comes from the original genuine feminism that I know and believe in. So we won’t ever agree on that…and I would say, as it seems to be your ‘safe and effective’ mantra..you have the problem, not me.

The expansion of trans rights has gone more in hand with state and institutional regulation of speech and behaviour….not just in relation to women and men but calling Welsh people Taff, or people of colour certain names, or calling gay people ‘poofs’ etc…not having hot-cross buns…because?…..celebrating Eid, but not St George’s day…etc…etc…this has been going on for years, and this is sadly an extension of it in my opinion…

…..and even though the trans lobby are small, people in positions of power…(just as many of them men) in the media, academia, law, the medical profession, police, Government both local and National have gathered around the ‘cause’….and now try to legislate the behaviours of all of us, rather than that tiny minority…

The why is something I don’t know….

I don’t know if you have read Lindsay and Pluckrose’s analysis of feminism, gender studies, queer theory with marxist and postmodern influences, in their ‘Cynical Theories‘? They trace the evolution of marxist feminism modified with queer theory and postmodern Derridean analysis of language to deconstruct the meanings of “man and “woman” whereby a dominant view within marxist feminism had it that “man” and “woman” were to be regarded as “constructions or representations – achieved through discourse, performance and repetition – rather than real entities”(P141).

The shift away from sex to gender was documented in Candace West and Don H Zimmerman’s 1987 paper Doing Gender in which they have a shift away from sex and towards gender, they “explicitly reject biology as a source of differences in male and female behaviours, preferences or traits”(P147)

This change was documented in a 2006 essay by Judith Lorber and followed up by further accounts of gender studies coming out of that by Judith Pilcher and Imelda Whelan ‘Key Concepts in Gender Studies’ 2017.(P144).

The page numbers refer to Lindsay and Pluckrose’s book.

Needless to say, coming out of STEM, I find this wild theorising coupled with reification utterly fascinating – and frightening.

Lindsay and Pluckrose also look at liberal feminism also diverting into intersectional or diversity feminism concerned with identity.

I am interested to know why you clearly take feminism so personally.

I don’t take it personally. I think the trans problem is being completely misrepresented and misunderstood.

Some women are trying to male this about them, a new form of misogyny. But it isn’t. The men in women’s loos and women’s sports is a sideshow. The real problem and danger is in schools. Driven by women, and taken up mostly by men.

If you aren’t involved in schools in some way you probably aren’t seeing it. But it’s a dangerous problem.

And it is linked to feminism. Its a kind of spin off from it. It appeals to many ultra.feminists and to teenage girls.

I always thought the point of support bras was for support.

I am looking forward to seeing Nike’s advert for jock straps.

It’s just nonsense, but so very few seem brave enough to say so.

My lady is fairly busty and a sports bra holds everything still while she’s active. I’m told they’re quite heavy and without one exercise would be painful for her.

Dylan’s plainly a boy, with (a pathetic attention-seeking complex and…) nothing whatsoever that requires the support of a sports bra. No matter what the activity nothing will bounce and nobody will know if the garment works or not.

I doubt he’s likely to get the snip, I hear that not many do – that requires true commitment and bravery. But if he does, then he can also model the jock strap for Nike and demonstrate it’s ability to hold a load of absolute bllx

Maybe we need to set up a truss fund.

Old news. Anyone with a moral compass will have been boycotting Nike since they started paying professional knee taking and perpetually whingeing victim Colin Kapernick to promote their sweat shop output.

Wasn’t Nike a goddess?

Yes..the Goddess of victory…I saw her beautiful statue in Warsaw once….

but you know, myth, history, stories…it can all be re-written can’t it?

People like an easy lie rather than the hard truth these days….

This makes perfect sense for the fashion industry, I don’t know why they didn’t think of using trans models to replace women sooner instead of forcing women to starve themselves to be a boyish shape. I always assumed the fashion houses needed women to be emaciated because they weren’t talented enough to design clothes to fit female curves. Nike has proved you don’t have to worry any more.

Is a boycott really necessary? Seems like Nike are sh*tting in their own nest.

One could easily form the opinion that Nike does not know or care about the difference between sexes. As a sports ware brand (I almost write in error “manufacturer”) one would have thought they knew the difference.

What next, Buck Angel being sponsored to advertise jock straps?

Another entity added to me ‘boycott’ list – from Paypal to Walkers crisps, to Penquin Books, the list just keeps expanding. Helping me save.

Matt Walsh is making the point that the mass boycotting you refer to is ineffective. Better to ‘flash’ target woke companies one by one, starting with Anheuser Busch. A list of their products … https://twitter.com/Travistritt/status/1643773257206693888

Thank you Nike for telling the female population that a man without breasts who tells you he is a woman is so much better at being a woman than the real thing.

In order to prove that you as a company actually believe in this “its what you say you are rather than what biology says” When can we expect to see a white person dressed as a black man rather like the minstrel show from the 70’s used in one of your ads for sports gear? After all if a man can profess to be a woman and its not allowed to be offensive to real women, surely a white person can put black make up on, claim to be black and it not be considered acceptable for black people to find it offensive.

So go on show us just how serious you are and not just a craven money grabbing go along with anything for the cash company

spot-on Hester…

An excellent suggestion

It is up to each individual ofcourse, but I will never purchase from any company that tries to stuff any ideology down my throat. The woke capitalists will not get any of my money if I can help it. I already asked my wife not to buy any DOVE products because of their TV ads that have black women in business suits staring in utter contempt at the camera. But when you take a look at TV ads these days all they seem to care about is putting as many different races on the screen as they can stuff in there. If a husband is white his wife will be black and vice versa. It seems these days that the woke capitalists pretend that they care about something other than profit and power precisely to gain more of both.

Seems to me that the black and other coloured people in tv ads and programmes are indicative of a slave market emerging to make up the numbers for an ever reducing pool of suitable, willing but unambitious white actors and actresses.

Well done Nike, for showing us that your sports bras are absolutely crap and not fit for purpose: you’ve had to use a flat chested bloke to advertise them! Great job.

It’s very difficult to argue with the logic of that argument.

Is it just me, but Dylan looks a bit like a brave little toaster, dancing around with a rictus grin, pretending everything is fine, when they are dying inside ?…

..plus he’s a funny looking little gink! LOL!

Fake beer, fake America, crap expensive shyte, made in Indian! Go campaign for sales there! Bunch of f-ing idiots!

Put your cock where your mouth is and get it cut off! Then I might believe you, freak

Not sports bra’s, Breast binding! Why doesn’t…it..bind its head and feet too? and then p*#s off!

Products to abandon!

Nike

Budweiser Family

•Budweiser

•Bud Light

•Budweiser Select

•Budweiser American Ale

•Bud Dry

•Bud Ice

•Bud Ice Light

•Budweiser Brewmaster Reserve

•Bud Light Lime

•Budweiser & Clamato Chelada

•Bud Light & Clamato Chelada

•Bud Extra

– Michelob Family

•Michelob

•Michelob Light

•Michelob Honey Lager

•Michelob AmberBock

•Michelob Golden Draft

•Michelob Golden Draft Light

•Michelob Bavarian Wheat

•Michelob Porter

•Michelob Pale Ale

•Michelob Dunkel Weisse

– Ultra Family

•Michelob Ultra

•Michelob Ultra Amber

•Michelob Ultra Lime Cactus

•Michelob Ultra Pomegranate Raspberry

•Michelob Ultra Tuscan Orange

– Busch Family

•Busch

•Busch Light

•Busch Ice

– The Natural Family

•Natural Light

•Natural Ice

– Specialty Beers

•Bud Extra

•Bare Knuckle Stout

•Anheuser World Lager

•ZiegenBock

•Ascent 54 (Colorado only)

•Redbridge (gluten-free)

•Rolling Rock

•Landshark Lager

•Shock Top

•Skipjack Amber Lager

•Wild Blue

– Seasonal Beers

•Sun Dog (spring)

•Beach Bum Blonde Ale (sum)

•Jack’s Pumpkin Spice Ale (fall)

•Winter’s Bourbon Cask (wntr)

– Non-alcoholic

•O’Doul’s

•O’Doul’s Amber

•Busch NA

•Budweiser NA

•Budweiser NA Green Apple

– Energy Drinks

•180 Blue

•180 Sport Drink

•180 Energy

•180 Red

•180 Blue Low Calorie

•180 Sugar Free

– Specialty Organic Beers

•Stone Mill Pale Ale

•Wild Hop Lager

– Specialty Malt Beverages

•Bacardi Silver

•Peels

•Tequiza

•Tilt

Also Stella Artois

Weak fizzy p*ss each and every one of them. & almost certainly turning boys and men into women and girls due to the hideously unnatural ingredients.

People who drink these products will not live long and happy lives. The manufacturers know it. The whole thing is based on contempt for customers and profiteering. See vaccines.

(

weak fizzy p*ss!

weak fizzy p*ss!

)

)

You are so right ️

️

I’m mad Jack Daniels has joined the ‘in crowd’ as well as I always liked it …luckily I’ve discovered Buffalo Trace….LOL!

There’s always an alternative!!

This is what Ted Nugent and Kid Rock think of the Bud Light et al campaigns. Definitely worth a watch…

https://youtu.be/ipElQEzsWKs

Brilliant…I put the Kid Rock on earlier, but the more the merrier and I like Ted Nugent…’truth, logic and common sense is Kryptonite to our governments, media and big tech’… absolutely….!

Since I don’t and never have bought a Nike product, and in any case likely never would, I find myself unable to boycott them.

How annoying.

There’s an American YouTube channel I occasionally watch where the presenter was commenting on the latest school shooting.

The assassin / terrorist was trans so he suggested that their pronouns should now be “was” and “were”.