A new paper in the Lancet has attracted some interest, both because it claims to find that the pandemic death toll is over three times higher than official Covid death figures suggest and because it seems to confirm that restrictions made no difference to outcomes. The authors say that while “reported COVID-19 deaths between January 1st 2020 and December 31st 2021 totalled 5·94 million worldwide”, they estimate that “18·2 million people died worldwide because of the COVID-19 pandemic (as measured by excess mortality) over that period”.

However, the paper is heavily dependent on modelling, so despite the welcome implication for the ineffectiveness of lockdowns, caution is needed.

The paper aims to “estimate excess mortality from the COVID-19 pandemic in 191 countries and territories, and 252 subnational units for selected countries, from January 1st 2020 to December 31st 2021”.

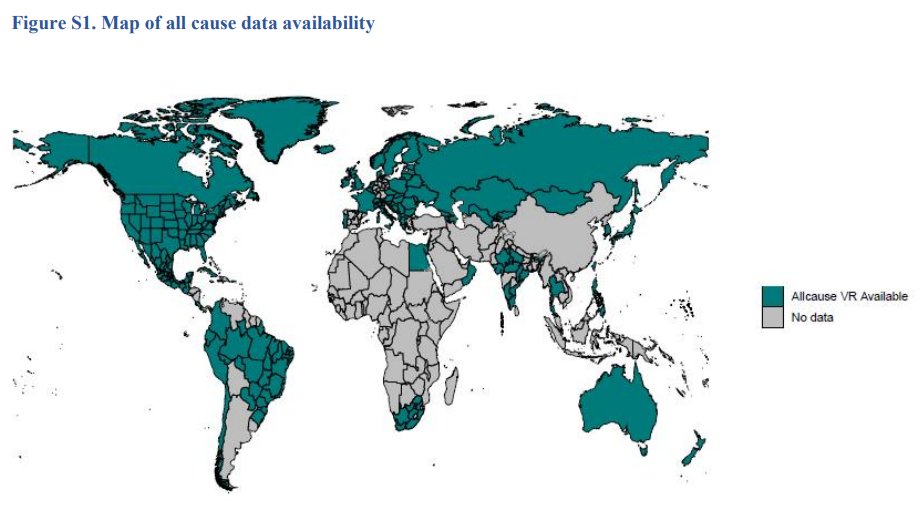

The relevant data were not always available, however, so the authors “built a statistical model that predicted the excess mortality rate for locations and periods where all-cause mortality data were not available”.

Not all excess deaths are Covid deaths, of course. The authors say that although they “suspect most of the excess mortality during the pandemic is from COVID-19”, excess deaths also include deaths from lockdown, including “deaths from chronic and acute conditions affected by deferred care-seeking”. However, there are currently insufficient data to distinguish Covid deaths from other excess deaths, they say, and while audits in Belgium and Sweden have suggested that excess deaths and Covid deaths are of a similar magnitude, audits in Russia and Mexico have suggested otherwise, as a “substantial proportion of excess deaths could not be attributed to SARS-CoV-2 infection in these locations”.

The authors used an ensemble of six models to estimate expected and thus excess deaths: “Excess mortality over time was calculated as observed mortality, after excluding data from periods affected by late registration and anomalies such as heat waves, minus expected mortality. Six models were used to estimate expected mortality; final estimates of expected mortality were based on an ensemble of these models.”

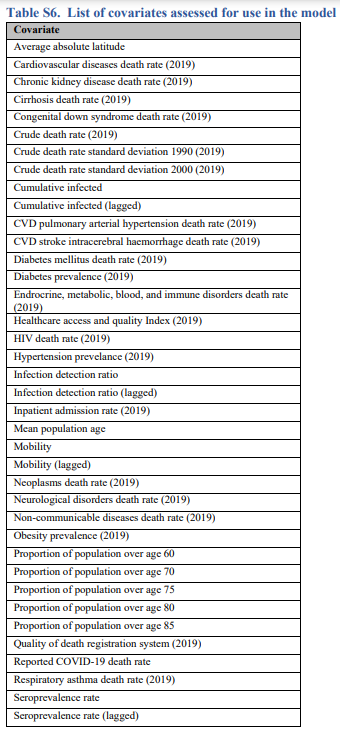

These models took account of no fewer than 38 covariates, as listed in the table.

The covariates included the latitude of the country or region, for reasons not fully explained – and as Dr. Clare Craig notes, the study appears to hugely inflate figures for equatorial countries and southern U.S. states.

The authors compare their estimates to those of the Economist, which they say “provides the most comprehensive assessment of excess mortality due to COVID-19 to date”. Although the Economist comes to a similar global estimate of 18 million excess deaths, it gets there in a very different way (suggesting the similarity is something of a fluke) as its estimates for individual countries and regions are frequently dramatically different.

There are dramatic differences in the estimated excess mortality counts between the two studies for many countries. The relative difference between the estimates from each study, defined as the ratio between excess deaths from the Economist study over those from our study minus 1, ranges from −382·7% (Vanuatu) to 2282·3% (China). In terms of absolute relative difference, at least a 25% difference is observed in 129 of 187 countries. Some 23 countries have absolute relative differences between the two studies of higher than 100%… Although the global total produced by The Economist was similar at 18·0 million (95% UI 10·9–24·4) excess deaths, which is about 212,000 deaths fewer than the estimate derived in this study, country contributions to the totals varied. The Economist estimated 192,000 fewer excess deaths for Mexico, 140,000 for the USA, and 140,000 for Peru, and 1·07 million additional excess deaths for India, 409,000 for China, and 193,000 for Sudan. For sub-Saharan Africa, the absolute relative differences range from 0·6% in Gabon to 310·7% in Burundi. The absolute relative difference is at least 50% among 21 out of 46 countries in the region.

These dramatic differences obviously call into question the reliability of at least one of the models. The authors themselves admit that the input into their models “can have a sizeable impact on the estimated expected mortality for a particular location”.

Perhaps though, the more sophisticated Lancet modelling is closer to the truth than that of the Economist?

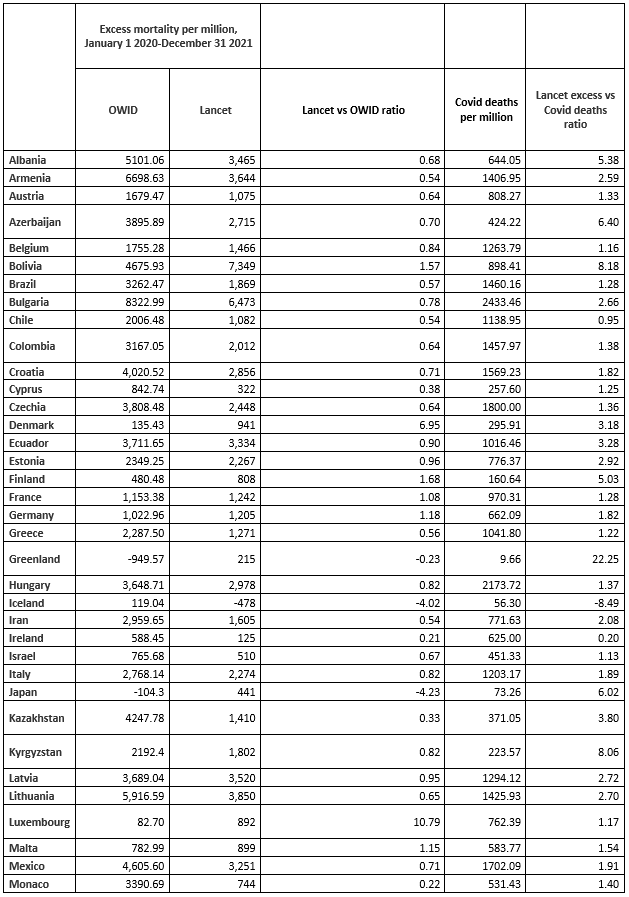

The problem with this hypothesis is that when we compare the Lancet estimates for excess mortality to those from Our World in Data (OWID) we again find huge discrepancies. OWID uses the expected mortality estimates from the World Mortality Dataset, which fits “a regression model for each region using historical deaths data from 2015-2019”. So still a model, but a more basic one than the Lancet‘s ensemble of six. It is based primarily on the pre-pandemic five-year average, while also aiming to “capture both seasonal variation and year-to-year trends in mortality”.

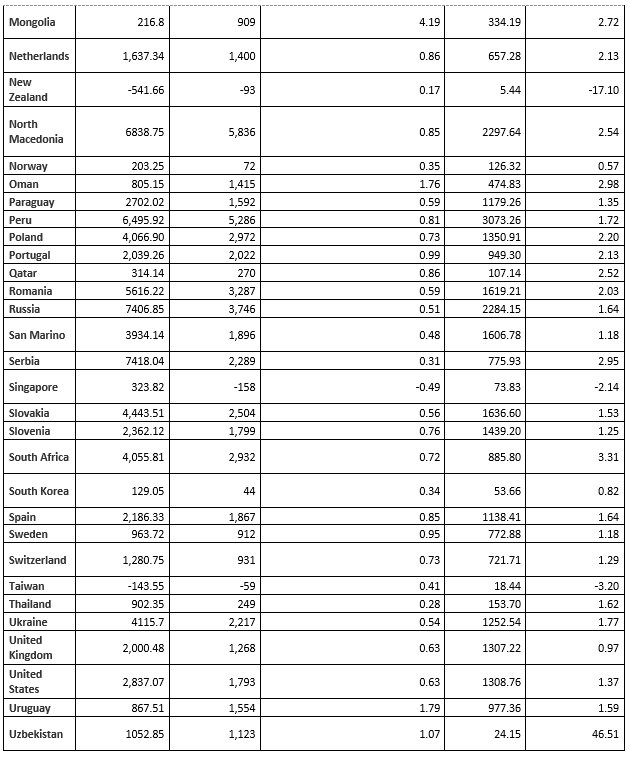

In the table below you can see the OWID estimate, the Lancet estimate and the ratio between them for each country where OWID has the relevant data up to the end of 2021. I have also included the official reported Covid deaths per million and the ratio of that with the Lancet estimate, which is one of the main outputs of the study.

The differences in many cases are huge. For instance, in many South American countries, such as Brazil and Chile, the Lancet estimate is around half the OWID estimate. In Ireland the Lancet thinks OWID overestimates excess mortality five-fold. On the other hand, in Japan, OWID finds negative excess, whereas the Lancet finds positive excess more than four times higher than the negative figure (a negative ratio in the table means the Lancet has found positive excess where OWID found negative, or vice-versa). In Iceland and Singapore, while OWID reports significant excess mortality, the Lancet says both countries actually have negative excess. This makes little sense. OWID uses a straightforward method for estimating expected and excess mortality, based on the five-year average. Why is the Lancet‘s modelling disagreeing with this so radically? The authors claim to have carried out “out-of-sample predictive validity testing”, which indicated “a small error rate (0·85%)”, but it’s hard to credit this when the results differ so greatly from a much more straightforward estimate of expected deaths.

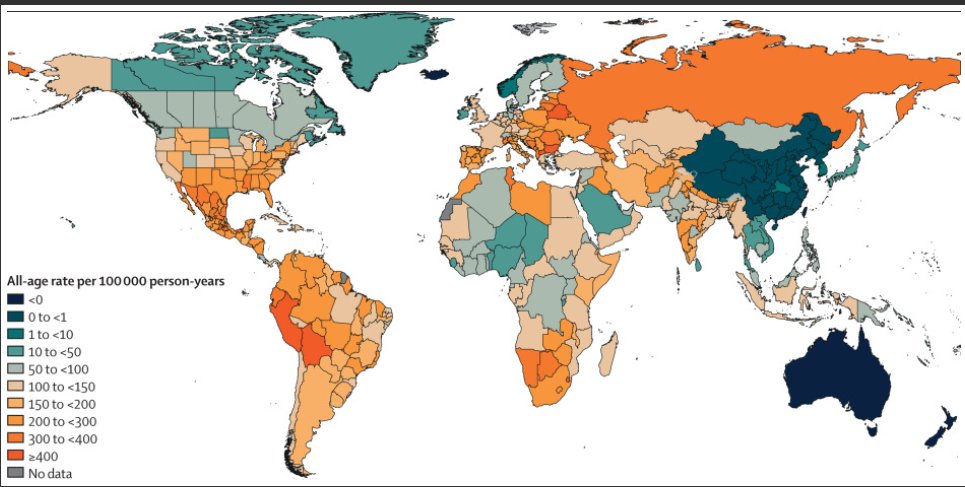

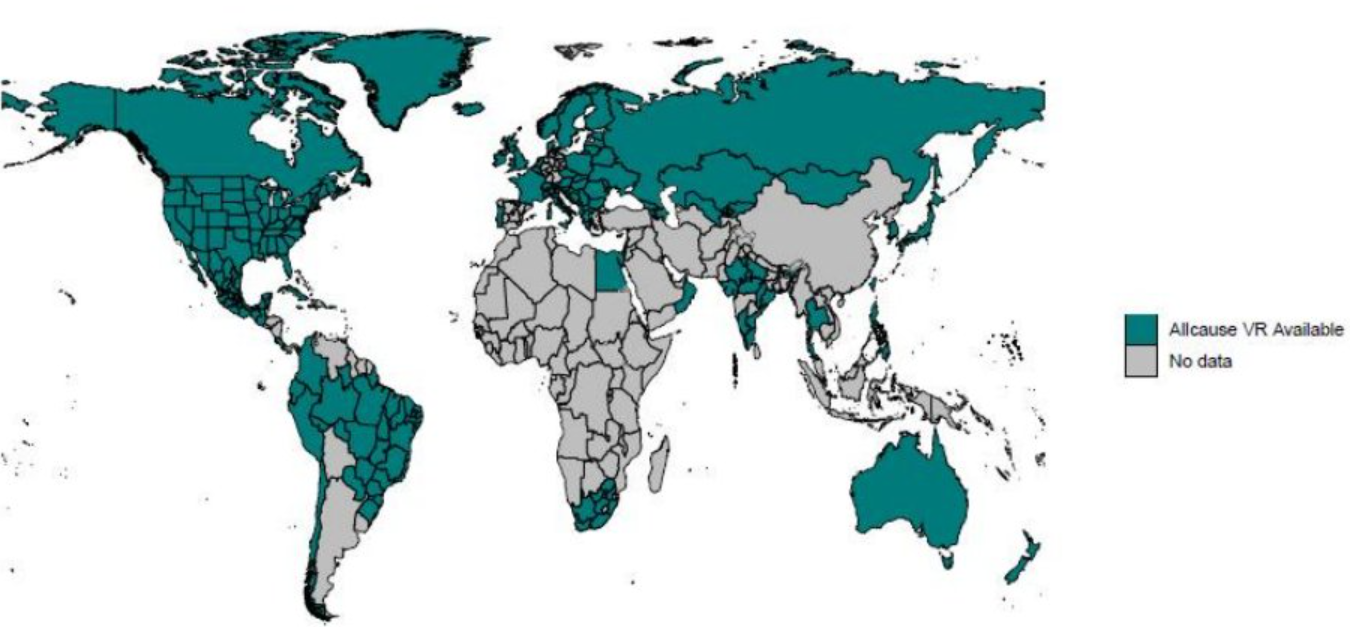

In the table above, many of the ratios are below one, indicating that the Lancet thinks OWID over-counts excess mortality. Yet overall the Lancet claims that Covid deaths are under-counted by more than a factor of three. Where do all the missing deaths come from? Some come from the non-Covid excess deaths that many countries experienced in the second half of 2021. But many of them come from regions where data are lacking, as depicted below, and the authors use modelling to fill in the gaps.

However, the reliability of this modelling is cast into doubt by the huge differences between countries or states within the same region. For instance, in Africa: “Low excess mortality rates were estimated across sub-Saharan Africa, with the notable exception of four nations in southern sub-Saharan Africa: Eswatini (634·9 per 100,000), Lesotho (562·9 per 100,000), Botswana (399·5 per 100,000), and Namibia (395·6 per 100,000).” Why would these four countries have excess death tolls so much higher than others in the region?

Also in India and Pakistan: “The most extreme ratios in the region were found in the states and provinces of India and Pakistan, ranging from 0·96 in Goa, India to 49·64 in Balochistan, Pakistan.” Why would some states in the region over-count Covid deaths while others under-count them by up to 50 times? In India, the Lancet claims that Bihar under-counted pandemic deaths 27-fold, even though Goa over-counted them. Is this really plausible?

Even in countries where we have reliable data, the Lancet makes extraordinary claims of under-counting. For instance, Japan has recorded 73 Covid deaths per million, and OWID even records negative excess deaths. Yet the Lancet claims Japan has under-counted pandemic deaths more than six-fold, and that it has actually had 441 excess deaths per million – a long way from negative. Similarly in Denmark, OWID has 135 excess deaths per million, but the Lancet thinks the country has under-counted seven-fold and that the true figure is 941 excess deaths per million. That’s over three times as high as its Covid death toll of 296 deaths per million. That fails the smell test.

The whole study seems to be a modelled fantasy. One to be avoided, I suggest, however useful some of the findings might appear.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“The whole study seems to be a modelled fantasy. One to be avoided, I suggest…”

So, DS, why on earth publish it?

Well said Aletheia, not that I bothered to plow through it.

If this sort of junk is being used to influence opinions we should be aware of it.

We’ll hear about it: the COVID warriors (you know – the ones who defend their anti-hero’s virility) will love it.

These modelled fantasies have consequences. They enable others to construct whatever version of events they want.

I am anticipating one colleague’s eagerness to tell me that I have vastly underestimated the frightfulness of the ghastly virus, and that he was correct in his insistence that it is the worsest disease in the history of humanity (with the possible exceptions of the Black Death and the Spanish Flu).

This fantasy will be cited by those who have not the least understanding of or interest in its problems.

Even the most absurd hypothesis claims to be backed by science and statistics. A cloak of respectability is given to people who have no scientific or mathematical education worthy of the name, and have only the most vague idea of history. That’s the problem – right there.

That’s why they have no idea of how to begin analysing excess mortality; and they just can’t understand why Russia would be bothered about what’s going on inside the Ukraine.

They have no capacity to challenge whatever fantasy is presented to them by their governments or the media, because they do not have the tools.

In the last decades, too many intelligent children were trained to use their brains to examine and discuss at length angels dancing on the heads of pins – absurd categorisations of beings, nations and conditions.

They will believe anything if it comes from far enough on high and uses magic words.

Obviously, as a warning of the absolute uselessness of politically influenced computer modelling.

See also climate modelling. There they usually take the average of many model outputs, as many as 132, from memory. Just think about it.

But just the ticket for policy based “evidence” making.

Because one day someone will throw this study in your face as evidence of something, and you will know exactly what it’s about.

For crying out loud, of course DS should publish these things. What happens when some tit with a ponytail confidently gives you his dumb opinion and it turns out to be based on the Lancet study – which you know nothing about because the DS hasn’t published it? This is why they bother! It’s a war of words which we MUST WIN!

Von Neumann said that with four complex parameters he could draw a graph that looked like an elephant, and with five he could make the trunk wiggle.

Given control of a model you can make it say anything. And modern politics has bought Into this concept bigtime – expect to see this model or similar ones being used to establish whole new sets of controls and mandates for the benefit of Big Pharma…

How many complex parameters to make the elephant piss all over the auther?

Every model or forecast is produced by calculations and algorithms designed to produce the required end result. If its a bit off, then just manipulate the data until you get it right

The only ‘model’ you need to judge whether ‘Covid’ was a serious pandemic caused by a deadly, previously unknown, mystery virus, or not, is the picture below which shows some ‘world leaders’ taking a ‘huge risk’ by all huddling together without face masks at the G7 meeting in Cornwall.

These people stole the freedoms of hundreds of millions of people, spread abject misery. fear and confusion throughout their countries, made vast amounts of money out of the ‘crisis’ – and are still getting away with it. ‘Covid restrictions’ continue to this day.

These peoples attempts to steal my freedom failed.

My life during Lockdown Proper was much the same as before, except no daily cafe breakfast or occisional hour in the pub.

I did not sucumb to “abject misery, fear or confusion” and do not believe the majority of other people did either despite what our MSM would have us believe.

I’ve met perhaps hundreds of thousands of people over the years, none of whom I am aware have died either with or of Covid.

Recently some have claimed to have ‘had it’ in the past but were not aware of it at the time; which would perhaps include myself.

After two years, I still don’t know of anyone who has had this claimed disease, or been in hospital or died from it.

I know four. But to be honest, it hastened their demise, rather than causing it.

Other “elements” had a part in that!

I know of several who have tested positive and some who have also had cold like symptoms at the same time, including my grandmother who is in her 80s, is in a ‘care’ home, has vascular dementia and heart disease along with being seriously overweight and according to the MSM should absolutely definitely have succumbed. Needless to say she and the others got through it just fine.

They have only had a mild setback – not a failure.

The Ukraine fiasco is the next step to steal your (our) freedoms ( inflation and food shortages caused by our own” sanctions” to be blamed on Russia!) and the Gates WHO has designs on your “bodily integrity.” signed up to and endorsed by Johnson.

Patel is limiting freedom to demonstrate with her Police Bill , Dorries is assaulting freedom of on-line expression and Rabb is going for our Human Rights -quite a package – while all eyes are on the ramped up media hysteria and False Flag events over in the Ukraine where any Russian version is censored !

For once EF you have made a valid point.

Can some talented person supply us with an image of what they might be looking at with such excitement and pleasure?

I have a feeling it was the Red Arrows but maybe it was Gates and Schwab descending from on high in a balloon.

There we go, Alter Ego

Bravo! Do I detect a touch of the Monty Pythons?

Alternatively

Or

That’s nailed it for me.

Thanks crisisgarden (and Brueghel?)

No worries! Third time’s the charm!

While looking up von Neumann’s elephant I came upon this interesting essay.

http://wavefunction.fieldofscience.com/2015/02/derek-lowe-to-world-beware-of-von.html

It seems that the complete failures of computational modelling are being noticed in very many technical fields. Apart from Climate Change, of course….

🥴LOLZOL

😀

The excess deaths are caused largely by the measures.

This happens all the time with large state intervention, where the solutions governments and bureaucracies apply to problems end up doing more harm than good.

A great example are all the welfare and racial equality programmes that they implemented in the US at the time of the civil rights movement. Up to that point all measures of development among the black population like literacy, income etc had been improving.

The progress was reversed the moment they started giving away welfare which took away the incentive to work and create family structures. The bussing of kids to school was also very damaging.

And far from admitting the damage it did, the social change warriors saw the deteriorating conditions for black people as proof that they needed to do more of the same.

This pattern of the state apparatus misused by socialists to shape society repeats itself all the time. COVID is just the most recent example.

Can you really say that “socialists” imposed these ludicrous measures? As far as i’m aware the vast majority of countries implemented them, no matter what wing of politics the government was on, and arguably Europe’s most socialist state – Sweden – was the outlier.

Now of course you might be inferring that the WHO – which was heavily influencing the response – is a quasi-socialist organisation. But if you’re arguing that large-scale socialist interventions are always disastrous, are you not favouring the “cock-up” theory of events?

The point i’m making is that if this was “conspiracy” rather than “cock-up”, and these measures were imposed with intended malice, then this automatically disqualifies them from being “socialist” as a key factor of socialist policy is not present – good intentions.

It would certainly appear that a large number of socialists were the useful idiots throughout the debacle, but I think we mustn’t make something political when, in my opinion, it was just simply criminal.

Check out the interesting founder membership and purpose of the “Trilateral Commission” which Kneeler Starmer belongs to and then look up Mussolini’s definition of “Fascism”. What do you notice?

Well, that Mussolini was very much a totalitarian and the Trilateral supports – whether knowingly or unknowingly – totalitarianism.

But totalitarianism is not socialism. In fact, it only took one simple Google search to find a real socialist who is critical of both Starmer and his links to the Trilateral:

https://labourheartlands.com/sir-keir-starmer-the-establishment-candidate-the-labour-leadership-race-and-the-trilateral-commission/

I use the term socialist to describe collectivist policies and the people who advocate them.

I don’t really care how people label themselves. If they generally tend to advocate for state solutions to problems, be it health care, racial inequality, economic inequality, education, then as far as I’m concerned they are pretty socialist.

If you believe in giving money away to a segment of society and bussing their kids long distances to schools to create more social equality, then in my books you’re a socialist.

Socialists also disapproved (note tense!) of the concentration of enormous amounts of wealth in private hands (like the manufacturers of the “vaccines”).

And state socialists weren’t the only variety. There were, and still are anarchist socialists.

For older socialists, the idea that the current crop of social democratic and “labour” parties are “socialist” is a joke.

Thanks for the clarity.

As per my response to David above, I think the Covid response is far better labelled totalitarian.

I don’t agree that all socialist or quasi-socialist policies are bad, in the same way I don’t think all ideas from conservative thinking are bad.

The key difference to the Covid response was that I was seemingly not allowed to decide for myself what was good or bad policy.

This is a thoroughly American idea and presumably caused by the fact that – insofar states go – the USA is an overgrown toddler. It’s add odds with a few thousands of years of European history. Eg, If they generally tend to advocate for state solutions to problems includes absolutism in Prussia (and elsewhere) and claiming that, say, Friedrich II was a socialist because he was a firm believer in state solutions to problems renders the term completely meaningless.

Agree.

The UK are going to burn £8.7 billions worth of PPE which was bought during the pandemic and is unsuitable.

Once I would have exclaimed, “Are you serious?!” Now I don’t even blink.

Some of it, even though it was bought and paid for by taxpayers and profits made, was made through slave labour, don’t you know, so virtue signally, its not possible to use it

Ah – that explains it: their hatred of oppression and their compassion for people everywhere.

Can this be burnt in a sustainable way and replace the fuel we’re now not getting from Russia?

Course not.

Apparently, they believe it can help towards the fuel crisis !!

The Russians are already planning to sell it to the Chinese – at a good price

Never mind, our £8.7 billion finds its way into deep pockets – after all ‘levelling up’ really means taking from the poor plebs and giving to the rich, the “Foundations”and the Corporates. More of it on the way!

Apparently Gates increased his personal wealth by one third during he “Pandemic”

I took the Lancet report to be another piece of pro-vaccine propaganda. Countries like India, Pakistan had so many excess deaths allegedly (and contrary to the Covid death numbers) because the percentage of population vaccinated was much lower? Pull the other one! Another example of modelling to suit the narrative.

This is no doubt one of many ‘studies’ that will be used to justify (to a largely brainwashed audience), the draconian measures of the last two years. The fact that it is not really a study at all will be lost on the bovine masses.

These “bovine masses” will determine our future – that’s what worries me!

I wonder if the people who come up with this rubbish will be so keen to produce similar stuff re the number of deaths that will result from the increased cost of living and fuel, along with the removal of free meds for the elderly and additional pressure on the NCS due to however many extra people are now in the uk.

Why don’t they just skip straight to the conclusion they want, i.e. that every death is down to Covid, Covid deniers, climate crisis or Brexit?

No-one denies Covid – only some of us know some of the whole truth about what it is, who planned it, who made it , who pushed it, who profited from it, where it came from and what the bigger picture is all about.

No “denial” there – just a thirst for knowledge!

Is there no such thing as real-world verifiable data anymore then? In my opinion the only models with any value or integrity these days are the one’s produced by Airfix.

The Inception approach to modelling. A model within a model within a model…….

Does the spinning top ever stop?

Thanks Will again for an excellent analysis.I hope it will be spread far as an antidote to swallow this Lancet article, which has so many flaws and creating biological not plausible conclusions.

deaths from chronic and acute conditions affected by deferred care-seeking in overstretched health-care systems

Or in the case of Britain, of understretched health-care systems.

“Lancet”…occupied territory. Nothing to see here.

‘World Morality Dataset’ lol

Don’t need to model that …

Knowledge about the real world can’t be generated by shuffling numbers around in computer program. For the sake of example, let’s assume the calculated numbers were perfectly accurate. Without knowing the real numbers, no one can possibly knows this and if the real numbers were known, the computer simulation wouldn’t be needed.

The old adage If you can’t dazzle them with brilliance, baffle them with bullshit also comes to mind here. Even in the hypothetical best case, when different six models are being used, five of them must necessarily be wrong. So, what’s the likely point of this theoretically unsound model inflation? Answer: Make it more complicated and hope the audience will be awestruck by that.

This whole article, unless I am misunderstanding, seems to be suggesting everyone should have three or more injections. Therefore the pharmaceuticals will still make their millions. We know the longer you take a medication the more likely you are to have organ failure. I saw it in my father and two of my aunts.

It seems to me that we should ignore any information coming from Government Departments at the moment. They are all to be mistrusted. I might add that we have two neighbours died recently. Both in their early 40s. Both healthy, middle class men who suddenly had heart problems. I will believe what I see with my own eyes.

It is a mute point as to which is the most dangerous SARS-CoV-2 or the modellers!

We still do not know how many people died of Covid as opposed to with it (most probably acquired in a hospital or care home). The modelling profession, which also plays an important role in predicting environmental catastrophe, needs to be regarded in a similar way to astrology. The veneer of respectability has given rise to a global racket. I suspect not one of them has been anywhere near a mortuary or carried out a post mortem.

Surely there’s no point in agonising over Lancet’s figures. It’s well discredited by now, isn’t it?

One problem I’ve spotted with the study is that the calculation of the rate per 100,000 appears to be systematically wrong.

For example, with the UK they estimate excess mortality at 169,000, which seems reasonable enough, if a bit on the high side, but with a population of about 67 million that should result in an excess mortality rate of 252.2, yet somehow this becomes 126.8 in the study.

The same pattern can be seen with the calculation of the reported Covid mortality rate and appears to be repeated consistently across countries, the authors appear to have consistently doubled the population, or otherwise halved the rate, which thus makes comparison with the Economist/OWID models meaningless.

None of this necessarily breaks the work, but the apparent inability to perform a simple calculation should raise red flags to anybody paying the slightest bit of attention (which rules out most journalists, unfortunately).

Perhaps more significant is the fundamental message. If you look at Germany for example, once you adjust for the error the authors are saying that OWID are wrong by 2.36 times, for Finland it’s x3.36 and for Denmark it’s a staggering 13.9 times.

What the authors are saying is that professional statisticians working for The Economist and OWID are unable to perform an excess mortality calculation for advanced first world countries with about as much data as you could possibly wish, ………… yeah, let’s think about that for a second……….. these are the same authors who are seemingly unable to divide one number by another without screwing it up, where’s my doubt emoji?

This sort of garbage really shouldn’t be published, it gets picked up by the MSM and reported as fact, and then recycled endlessly on social media as proof that lockdowns don’t work, whatever your view on the subject the debate should be based on fact and not the kind of models that a random bloke on a football forum can take one look at and say “that’s b*******”.

As an addendum, what the study also says is that Germany reported 110,000 deaths but really suffered 200,000, and that Denmark, previously thought to be one of the least affected countries in Europe suffered almost as much as the UK, AND THAT NOBODY NOTICED!!!!!!!!!!!

C’mon guys, some basic common sense, please.