by Dr Clare Craig FRCPath

On February 1st the Oxford Vaccine Group published their latest findings on the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine. While the findings are encouraging, the way they have been interpreted is questionable. The study is underpowered for the conclusions that are being drawn from it and there has been extensive data mining undertaken retrospectively in an attempt to draw more powerful conclusions.

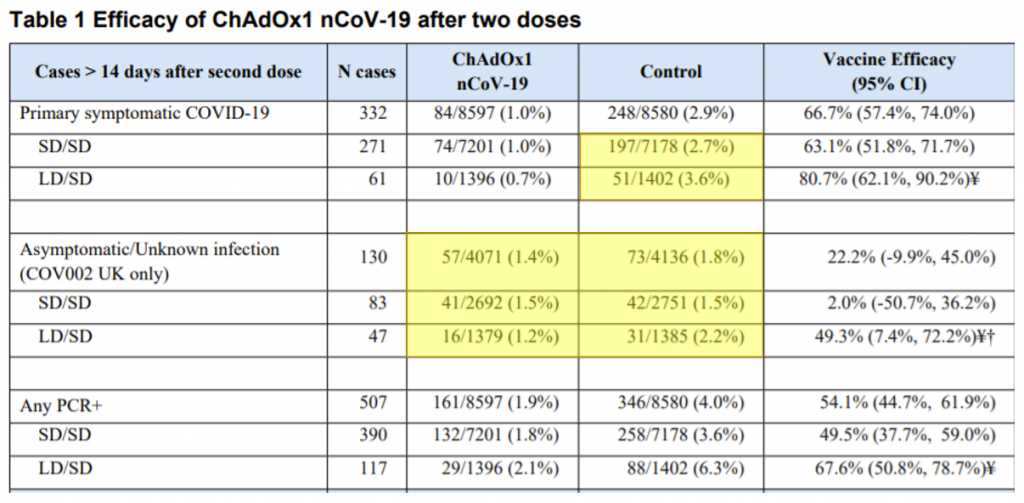

They concluded that in the vaccinated group two thirds fewer people were infected. Despite admitting that they did not study transmission, they still commented on it. The conclusions reached were the overall percentage testing positive was 54% lower “indicating the potential for a reduction of transmission”. The 54% figure was deduced from positivity including asymptomatic positives. This is not a reasonable conclusion to draw on two counts. They have assumed that asymptomatic positives are a major source of transmission and there is minimal evidence to support that assertion; and they failed to account for false positive test results.

Asymptomatic positives were looked for only in the UK participants. They have not stated how often these people were tested, but it can be inferred that they were tested 10 times each on a weekly basis for follow up from day 22 to day 90. That is 82,070 tests. A remarkably low false positive rate of 0.16% would be enough to account for the asymptomatic positives that they found. Repeat testing will only exclude false positives if a negative result is used to overrule a previous positive result. The criteria for calling a positive were not disclosed in the paper and it is assumed that a single PCR positive test was considered significant.

Instead of realising they had a false positive problem there has been over-interpretation of the results.

They note that there was no impact of vaccination with standard doses after 90 days on the number of asymptomatic positives. There is no reason to expect an impact when it is appreciated that these are false positive results.

Note that the difference between the two control groups in the symptomatic positives (at the top of the table) is significant – 2.7% infected vs 3.6% infected. If there is potential for that much difference between the control arms, then the impact of the difference between the control and vaccine arm has to be called into question. There does appear to be an effect of vaccination in the symptomatic group, but the effect is not as dramatic when considering that one control arm had a 25% reduction in symptomatic positives by chance alone.

For the asymptomatic positives, again, the difference between the two control arms – 2.2% vs 1.5% – is of the same order of magnitude as the difference it is claimed was due to the vaccine in the low dose arm – 1.2% vs 2.2%. Furthermore, when two standard doses were given, no difference was observed at all – 1.5% were asymptomatic positives in both control and vaccine arms.

How can the vaccine be having an impact if it is possible to find the same impact by randomly assigning people to two different control groups?

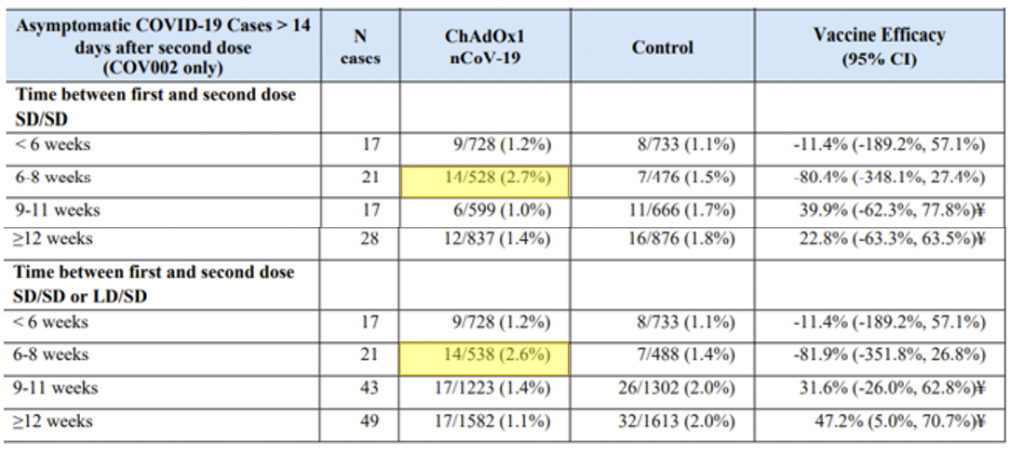

Looking at the different dosing schedules it is clear that the highest number of asymptomatic positives were actually seen in the vaccine arm with a 6-8 week interval between doses. However, this cannot be over-interpreted. The message is that all of the results in the asymptomatic positives were background noise and should be ignored.

Finally, it is worth noting that although they include this sentence:

the analyses are presented here to provide a rigorous peer-reviewed interrogation of updated data.

There has been no peer review at this stage and we must hope that the peer reviewers take a dim view of their over-interpretation of this data.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpLatest News

Next PostLatest News