by Jonny Peppiatt

This topic is a particularly interesting one for a number of reasons: first, because you’re probably thinking, “Of course loneliness is a major cause of mental illness, so why should I spend five minutes reading about something I already know?” – read on and find out; second, because we are all aware of quite how particularly pertinent it is right now; and, third, because it was the most significant factor in my experience with depression.

Before we go any further though, I think it would be a good idea to explain what loneliness is, because it isn’t as simple as not having friends or being alone. It is a process within the brain that has been designed by evolution that gives you a feeling as a result of believing you have limited or no connections that provide a sense of mutual aid and protection with other individuals.

Human beings began as a species on the savannahs of Africa but survived as a species because of cooperation and tribal support. If you were an individual who became separated from your tribe, no one would care for you should you fall sick, you would be unable to hunt effectively, and you would be vulnerable to predators; and it is because of this that the brain developed a way to send an urgent signal to reconnect with your tribe in the form of loneliness and a sense of insecurity.

In today’s world, however, the connection that we need is slightly different: mutuality remains a necessity, and aid and protection are still important, although these come as a by-product of simply caring for one another; but avoiding loneliness is also about sharing something that matters to both sides of the connection, which gives rise to an interesting facet of loneliness: it has varying degrees not just in intensity but also in breadth.

Take, for example, three things I care deeply about: writing; cricket; and the queer community. I have people I discuss literature with, and I have people with whom I swap articles and pieces of work with; I have friends I play cricket with, and I have friends waiting around the corner to go to cricket with; but I have no queer community. Somehow, I have ended up with no friends – who would really truly understand – with whom I can discuss the struggles our community faces internally and externally, or the wondrous strides that have been made, or anything else that can be ‘explained’ but cannot be genuinely understood by someone outside of the community, someone who hasn’t lived it, and, because of this, I often feel intensely lonely in this very important aspect of my life.

But that’s enough about me for now, because it’s time I shared some of the science – suspend scepticism, if you please – around the effects of loneliness. The first comes from a paper by John Cacioppo and William Patrick, Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection (2008), in which participants were asked to spit in a tube and note down how lonely or connected they felt in that moment nine times a day. This allowed their cortisol levels to be measured and plotted against their levels of loneliness. What the data suggested was that an acute sense of loneliness produced the same amount of stress as when someone experiences a physical attack by a stranger.

Six years later, Cacioppo published another paper on loneliness that documented the long-term health impact was just as dangerous as obesity; and Lisa Berkman in 2015 published The Village Effect: Why Face-To-Face Contact Matters, which showed the risk of cancer, heart disease, and respiratory problems were all increased in individuals experiencing loneliness, concluding that loneliness makes us two to three times more likely to die on any given day.

But none of this answers the question as to whether loneliness is a cause or an effect of depression, and so Caciappo performed a further study over a number of years where participants were given an extensive personality test a number of times over the years to gauge those who had suffered, or were suffering, from depression as well as their levels of loneliness. What he discovered was a lag between feeling lonely and experiencing a depression that confirmed loneliness preceded depression. Moreover, he was able to create a scale of loneliness and plot the chances of an individual experiencing a depression against that scale finding that were someone to move along the loneliness scale from feeling “50% lonely” to “65% lonely”, their chances of developing depressive symptoms increased eight times.

Following this study, the believed progression of loneliness became established: an individual loses meaningful connections and becomes lonely; this loneliness creates a sense of insecurity (that may develop into anxiety) that causes a retreat from society; the retreat from society reinforces the lack of connections and develops into depression; the depression creates a belief that no one will care enough about them for a connection to ever be established again.

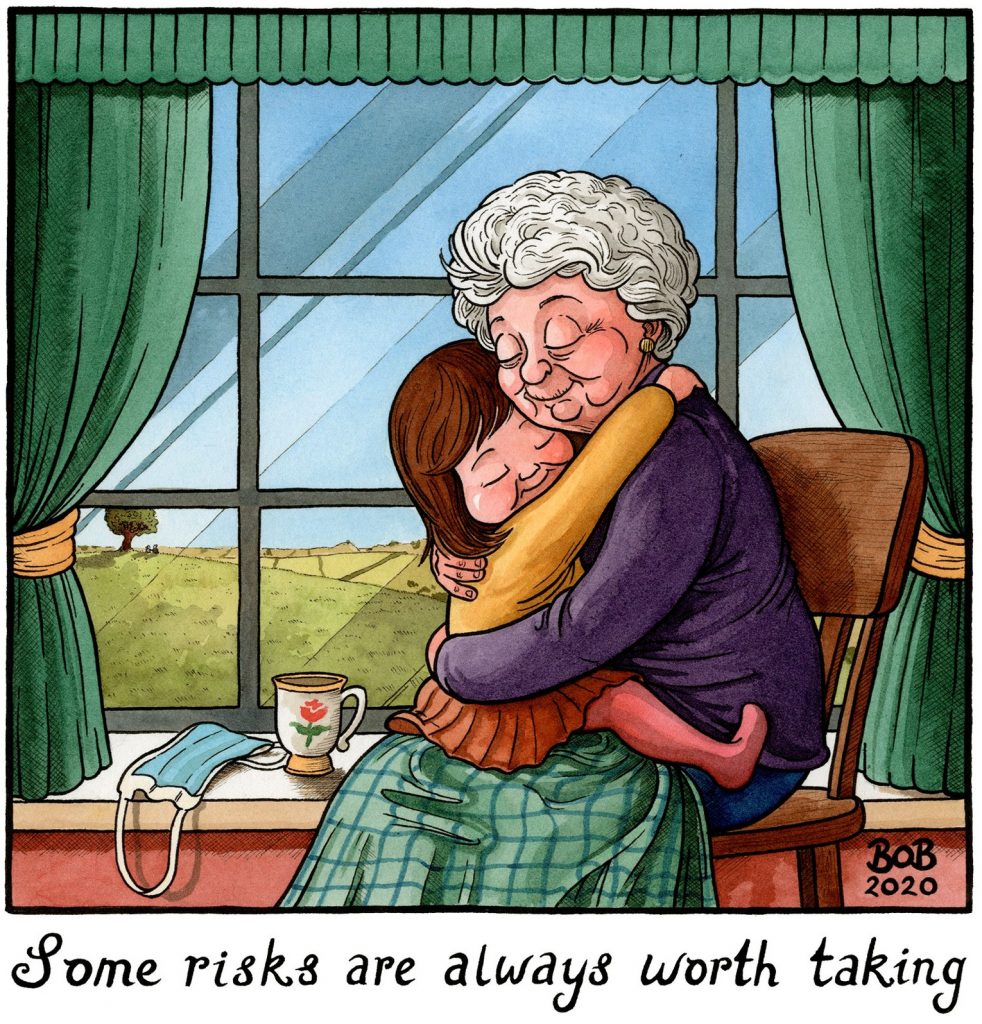

It’s a frighteningly familiar story, and a story that has been forced upon individuals in the last nine months.

One rebuttal I’ve heard very often when discussing mental health, and one that always frustrates me, is the suggestion that depression and anxiety may not have actually increased in recent times, people are just more comfortable talking about it today. It’s particularly frustrating because it’s very difficult to disprove directly. However, it is possible to disprove by proxy when it is accepted that loneliness is a major cause of depression and anxiety, as there are many, many studies showing that loneliness has increased dramatically over recent times.

One of these features in the M. McPherson et al. paper, Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks over Two Decades (2004), that asked individuals how many close friends they had that they knew they could rely on. At the start of the two decades, the modal response was three; at the end of the study, the modal answer was none.

All the evidence suggests that loneliness has been on the rise as a result of our movement away from community and tribe-like living; group activity engagement and community participation have been on the decline for decades; and we started replacing genuine face-to-face connection with screen-mediated contact that simply does not meet our psychological needs as human beings long before the Covid-response crisis, allowing ourselves to be fooled that we have enough connection by the little short-term dopamine hit we get when our phones buzz and that little notification pops up.

There are ways in which we can make our world just a little less lonely though. The first focuses on your passions; once you know what they are, be vocal about them and share them with those around you – you will find someone to share that passion with you quicker than you might think; and, if it is something that can be done in a group like playing a sport, or music, then make that time available so you can do it – that community is vitally important, and I do not use that word lightly.

The second focuses on looking after those around you; remember that the centre of a meaningful connection is mutual aid and protection, a sense we get from caring about someone and knowing that they care about us too. It takes next to nothing to remind someone you care about that you do care about them, and it does wonders to keep that truly toxic feeling of loneliness away.

Donate

We depend on your donations to keep this site going. Please give what you can.

Donate TodayComment on this Article

You’ll need to set up an account to comment if you don’t already have one. We ask for a minimum donation of £5 if you'd like to make a comment or post in our Forums.

Sign UpEternal Lockdown, Wooden Horses and Shiny Things

Next PostLockdowns and the Death of Liberal Education