The coronavirus care-home scandal has been smouldering away in the media for some time, flaring now and then into a headline issue. During PMQs on May 13th, for instance, Sir Keir Starmer managed to bump the issue back up the agenda, skewering Boris with a quote from guidance issued very early on into the outbreak by Public Health England (PHE). According to Sir Keir, the guidance had advised that it was “unlikely that people receiving care in care homes will become infected”. Although it didn’t seem particularly convincing at the time, Boris’s subsequent claim that Sir Keir had quoted from the guidance “selectively and misleadingly” turns out to have been fair – the quote in question was preceded by a note that the guidance was “intended for the current position in the UK where there is currently no transmission of COVID-19 in the community”. At the time of issuance this was true. Alas, the media had its story and the political damage had been done. (The guidance both politicians were referring to is here). What’s unarguable, though, is the grim seriousness of the situation within UK care homes. If the central aim of the UK Government’s lockdown policy was to protect the most vulnerable, then it simply hasn’t succeeded in the social care sector. As the Health Foundation has noted, relative to the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in England and Wales, care homes have seen the biggest increase in deaths over time compared to deaths that have occurred in other settings. Data released by PHE recently (and cited in the Independent) showed more than 650 care homes were now declaring outbreaks of coronavirus. As of May 15th, deaths in care homes from all causes are starting to stabilise, but remain 159% higher than at the start of the COVID-19 outbreak. Again as of May 15th, that number of care home deaths due to COVID-19 stands at 8,244. That’s nearly a quarter of all COVID-19 deaths recorded in the UK.

So what’s happened?

There are some sad but inevitable reasons for the over-representation of elderly care-home residents in the UK’s COVID-19 mortality figures. As this HPA report makes clear, care homes are naturally vulnerable to outbreaks of airborne respiratory diseases: firstly, infections are able to spread quickly because of close contact between residents in what is largely a closed environment; secondly, and due to the nature of their work, carers are regularly in close physical proximity to residents, thereby unintentionally spreading the infection when there’s isn’t appropriate protection (more on this point later); and thirdly, residents are often elderly and have other underlying diseases (the BBC has a good summary of these points).

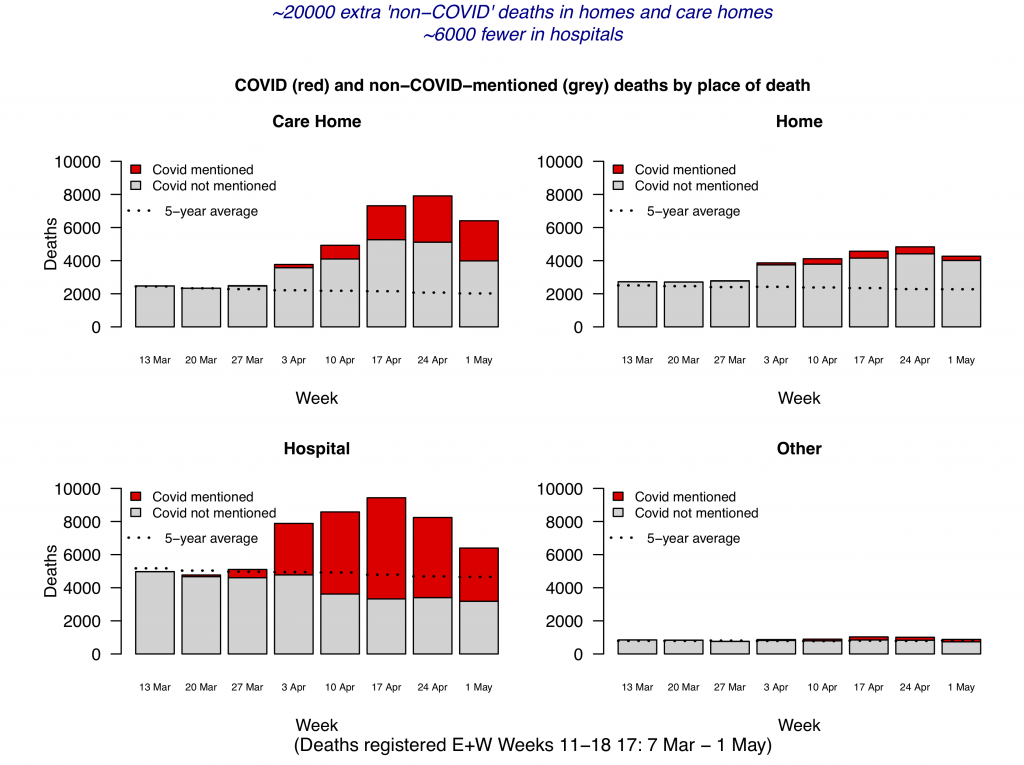

But as many commentators have been keen to point out, there are also various social and political factors at play. In fact, what we’re really dealing with –when it comes to care home deaths – are two distinct, yet interrelated issues. The first is: Why have there been so many care home deaths that we know, or strongly suspect, to have been caused by COVID-19? The second issue is a little more complicated. It’s to do with why there have been so many “excess deaths” in UK care homes that we know, or strongly suspect, have not been caused by COVID-19? It’s worth taking these in turn. But in the meantime, you can get an idea of what this second issue is all about, thanks to Professor David Spiegelhalter’s brilliant set of graphs below. To locate the unusual “excess deaths” in care homes, take a look at the graph at the top left, and pay attention to all the bits of grey in each bar that appear above the horizontal dotted line.

Fail to Prepare and Prepare to Fail!

Was a lack of planning and preparedness in the social care sector a factor? Professor Martin Green, Chief Executive of Care England, certainly seems to think so. In a stark and, as it turns out prophetic, warning on March 10th he said he feared widespread care-home deaths were inevitable if the virus swept the country. Speaking to the Independent, he hit out at what he said was the Government’s ignorance of social care and its importance.

“The system is gearing up for an NHS response, not a whole system response. I believe there is a real ageism issue here,” he said. “We haven’t heard any detailed plans. All we have heard is there are contingency plans. There is a complete lack of information.”

The fragmented, privatised and for-profit nature of social care provision in the UK has also been foregrounded as a possible problem here. The Care Quality Commission (CQC) and PHE aside, did a lack of overall control and joined-up thinking contribute to the crisis? David Rowland, Director of the Centre for Health and the Public Interest at the LSE, has written a good piece on this, looking at the political economy of social care in the UK and how COVID-19 has exposed serious, structural flaws in its current operating model. He points out that in one local authority, as many as 800 different care businesses are delivering care services. That sounds like a pretty difficult system to control from the top down. This Guardian piece from September 2019 also gives pause for thought. So too does the manner in which PHE, the CQC and the Department of Health and Social Care have repeatedly passed the buck in relation to who should carry out care-home testing (again, more on this later).

Hospital- and Community-Testing Issues

A lack of COVID-19 testing in the social care sector has been a huge area of concern for many commentators. As early as April 24th, for instance, the Telegraph reported scathingly on a government diktat that NHS hospitals should move hundreds of elderly patients to care homes. Two Government policy documents published on March 19th and April 2nd (which, by the way, you can’t see anymore because they’re currently being “reviewed” – check out the covering info on the gov.uk link here) instructed NHS hospitals to transfer any patients who no longer required hospital-level treatment back into the care home system. The aim here was, of course, to increase the NHS’s critical care capacity because of the epidemiological modelling highlighting the risk of it being overwhelmed. The Government also set out a blueprint for care homes to accept patients with COVID-19. But at that point, clinicians could only decide which patients did or did not have COVID-19 on the basis of their symptoms, not a PCR test. According to one senior manager at the NHS who spoke to ITV recently, care homes may have unknowingly been receiving coronavirus patients from NHS hospitals very early on in the outbreak. Government care home advice prior to April 15th (which, again, you can’t see anymore because they’re currently “reviewing” it – check out the covering info here) said that “negative tests are not required prior to transfers/admissions into the care home”. The Prime Minister has now made clear that the Government has “a system of testing people going into care homes” and that testing is being “ramped up”. Good to hear, of course. But quite late in the day.

Concerns have also been raised around testing capacity inside care homes. As the Guardian reported on May 12th, ministers have admitted it will be more than three weeks before all homes are offered tests. Detailing a series of emails between the CQC and care home managers, they paint a picture of a system that is – in the words of one public health director – “shambolic”. The BBC has also noted that although more than 400,000 people live in care homes and are looked after by a workforce of 1.5 million, the number of tests carried out in the sector so far remains in the tens of thousands (although, as of May 15th, the Government was suggesting that all residents and staff in care homes will have been tested by early June – see here for more). That’s clearly not enough testing. To date, then, the major problem in care homes seems to have been an inability to adequately separate COVID-19 cases from non-COVID-19 cases. It’s not particularly difficult to see why that might have allowed the infection to spread like wildfire through care homes full of vulnerable, elderly people.

Difficulties in Accessing PPE

A lack of adequate PPE in care homes has also been identified as a possible causal factor. The Financial Times reports that over the Easter period, the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services wrote to the Government complaining that “shambolic” national delivery efforts had produced “paltry” supplies of essential kit to a care sector treated as an “afterthought”. In April, the government put the firm Clipper Logistics in charge of setting up a central hub for the supply and distribution of PPE. Perhaps unsurprisingly to those who’ve followed the chequered history of public-private outsourcing initiatives in the UK, the online ordering system is yet to be rolled out. According to Wired, part of the problem lies in the structuring of the highly-fragmented social care market in the UK. This for-profit system, largely privately owned, has meant that collective action to deal with the spread of COVID-19 has often been thwarted. As David Rowland, Director of the Centre for Health and the Public Interest hints, because most care homes are operated by separate businesses in competition with one another, they don’t buy in bulk, together, from (usually) large suppliers, but end up purchasing PPE directly at highly inflated prices from (usually) smaller suppliers whose distribution and delivery chains are often less reliable and more prone to breakdown.

The Black Hole in the Care Home Figures – Excess Deaths

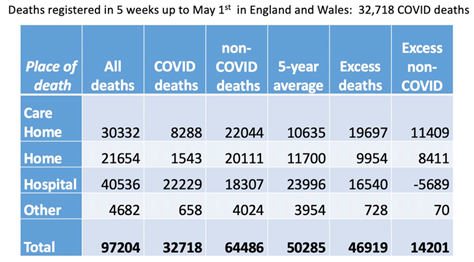

So far in this summary, only those care home deaths caused directly by COVID-19 have been considered. But there’s also a big issue with increased mortality in care homes not related to COVID-19 (see the above graphs). According to Professor Spiegelhalter’s analysis (available here), this issue shows up as a pretty big black hole in our care home death figures. For the five weeks up to May 1st in England and Wales, care homes and homes would, if in line with the five-year average, have recorded 22,500 deaths. (There’s a lag in collecting this data, so May 1st is currently as far as we can go with this – but see the table below). The Science Media Centre also has a nice breakdown of this data (see here).

In fact, what they’ve ended up with are 52,000 deaths. This equates to nearly 30,000 extra deaths across care homes and homes. (Technical note: “care homes” comprise patients receiving long-term residential care outside of the patient’s house; “homes,” however, is a category that includes more than just “normal” family households – it also includes home care provision where social care providers visit the elderly in their own homes. So both of these categories include large proportions of the same type of person: elderly, vulnerable, and in need of regular contact with social care staff.) The problem is that only around 10,000 of those deaths have been labelled as COVID-19. This means that around 20,000 (11,409 + 8,411 = 19,820; see the table above) extra non-COVID-19 deaths have been registered in the community over the last five weeks. (It’s worth noting here that Professor Spiegelhalter’s estimates tally with the work coming out of LSE’s Care Policy and Evaluation Centre – they’ve recently estimated in excess of 22,000 deaths during this same period.) If around 6,000 deaths (5,689; again, see the table above) have been “exported” from hospitals (as per Professor Spiegelhalter’s analysis), this still leaves around 14,000 excess deaths. Some of this excess will almost certainly be the result of under-diagnosis of COVID-19. As the Daily Mail points out, the true scale of the crisis in care homes has probably been masked by a lack of routine testing, meaning thousands of elderly residents may have died without ever being diagnosed. Some of this excess could also be due to the inherently fuzzy nature of medical death certification. (See the BMA on this.) But even taking all of that into account, you’re still left with a lot of unexplained, excess deaths.

One likely explanation is that some of the excess is comprised of care home residents with other diseases who were not admitted to hospital when they should have been. At a recent Science Media Centre briefing, the Professor of Epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine David Leon said: “Some of these deaths may not have occurred if people had got to hospital. How many is unclear. This issue needs urgent attention, and steps taken to ensure that those who would benefit from hospital treatment and care for other conditions can get it.” The Health Foundation’s recent analysis of up-to-date emergency care admission figures certainly gives weight to this idea. As of May 14th, A&E visits were 57% lower last month than in April 2019. They also note “particular concern about the implications of a reduction in A&E visits for acute conditions such as stroke and heart attack” (i.e. two conditions that are likely to be over-represented within care home populations). Spiked have a great Q&A with Knut Wittkowski, former Head of Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Research Design at the Rockefeller University’s Centre for Clinical and Translational Science, that touches on this issue. But there’s something else that’s potentially a bit troubling here. According to Skills for Care, the care sector had approximately 120,000 vacancies prior to the COVID-19 outbreak. That’s a big staff shortage. As the BBC points out, this existing problem has been exacerbated by staff (in the absence of adequate testing procedures, see above) having to self-isolate if they or a member of their family has shown potential coronavirus symptoms. In addition, and to prevent the virus spreading between care homes, the Government – early on in the outbreak – requested that staff didn’t work in more than one care home.

So have some care home residents not been getting the care that they needed? Have early signs and symptoms of other, non-COVID-19 related symptoms, potentially not been caught early enough due to staffing shortages? It’s impossible to say right now, of course, but what price a public inquiry into this when the dust has settled on a post-COVID-19 UK?

Further Reading

‘Coronavirus outbreaks at four in ten care homes‘ by Francis Elliott, Times, 18th May 2020

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Have you spoken to Dr Malcolm Kendrick, he works in carehomes, he’s been speaking out about this https://drmalcolmkendrick.org/2020/05/11/how-to-make-a-crisis-far-far-worse/

One of few remaining Doctors with ‘common sense’, recommend his book ‘Doctoring Data’ a real eye-opener.

One of the reasons for so many deaths in care homes is that it was a disaster waiting to happen

https://hectordrummond.com/2020/05/18/daphne-havercroft-covid-19-how-the-nhs-protects-itself-by-neglecting-the-elderly/

NSW following the same NHS protocol

Another reason for so many deaths in care homes is that the NHS and local authority goal is to spend as little money as possible on the care needs of the residents. Many of them are approaching the end of their lives and they are not getting the health care they need to reduce their risk of succumbing to serious diseases because the NHS downplays their health care needs to avoid having to provide the care it free at the point of need. Local authorities go along with this.

People whose care needs are primarily health as opposed to social care are legally entitled to have all their care paid for by the NHS, under NHS Continuing Healthcare (CHC).

Despite people living longer with complex health needs, the number deemed eligible for CHC has fallen and there is a post code lottery. This problem has been brewing for a long time, exacerbated by reduction in the number of acute hospital beds.

http://www.lukeclements.co.uk/continuing-health-care-funding-and-end-of-life-care/

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/02/27/vulnerable-pensioners-dementia-facing-crippling-care-bills-following/

You would think that local authorities would push back against the NHS and not accept responsibility for people whose care needs might be primarily health needs and therefore outside the local authority’s legal remit, but they don’t and cave in.

http://www.lukeclements.co.uk/nhs-chc-and-supine-council-leaders/

Of course not everyone in a care home is eligible for NHS CHC, but such is the NHS enthusiasm to downplay all health needs, that there is a risk that provision of routine, health care, free at the point of need, including end of life and palliative care planning, is patchy at best, so the residents are sitting ducks when a nasty virus enters their care home.

Everyone in a care home is registered with a GP and many practices look after all the residents in a care home, doing the weekly equivalent of ward rounds. Therefore what risk assessments did GPs do before allowing hospitals to discharge recovering Covid-19 patients into care homes in order to protect their patients from unnecessary risk of harm and death?

I think the answer is in Dr Kendrick’s blog.

https://drmalcolmkendrick.org/2020/05/11/how-to-make-a-crisis-far-far-worse/

“The bullying began. Of course, it wasn’t called bullying, but hospitals needed to be cleared out and nothing and no-one was going to get in the way.”

Obviously there were no risk assessments.

Thanks for this – will have a look at these links. Very helpful.

would you knowingly give someone with ‘distressing shortness of breath’ a drug with ‘respiratory depression and respiratory arrest’ as a known side effect (according to manufacturer’s safety warning)