During the time I was a secondary school teacher I saw the world of predictive modelling up close for the first time. The whole school system was built around various bought-in systems that purported to show each student’s projected academic future entirely in terms of data performance. Every year the predictions turned out in some way to be wrong. The reaction was always the same: more data was obviously needed, and the school annually turned to some new and expensive modelling service.

When the modelling appeared to be ‘right’, or nearly so, the fallacious and spurious assumption was always made that this was a direct result of the actions the teachers had taken, and the policies dictated by the school leadership. It was of course classic false logic – superstition, even. No one ever created a control class taught a different way to find out if the outcome following the intervention was different.

This reached its eccentric climax when we were told to enter the tracking data that matched the predictions. Thus, the predictions turned out to be ‘correct’ and all was at peace. I kid you not. That really happened. Some teachers even went to see the head to ask if that was really what they had been told to do. They had.

Modelling is and always has been a part of human life in some shape or form. It’s borne out of a desperate need to be able to predict the future. It injects certainty in a dangerous world, reassures us and operates hand in hand with weather forecasts. In fact, virtually nothing is truly predictable. One of the few phenomena that is predictable is the eclipse. Eclipses really do obey the rules. On August 21st 2017 I stood by a field in Nebraska and watched a total solar eclipse happen to the second, just as predicted.

Unfortunately, eclipses have imbued science with the wider conceit that all sorts of phenomena can be predicted by measuring data and applying mathematical principles. Eclipses, however, are affected by a few straightforward circumstances and none of them includes human agencies. Nothing else in our universe, including life on this planet, is governed by anything quite so measurable.

Modelling is thus a useful tool, a starting point but not a system of absolute laws by which the universe operates unfailingly, or if it is those absolute laws remain largely out of our reach. Modelling is a set of approximations and only incorporates what the modeller thought to put into it. (Garbage in, garbage out.) The reason school results never match the modelling is because the modelling can never take account of the endless variables every student is affected by. There are techniques designed in some way to include these but of course it is patently impossible to do so comprehensively. Exactly the same applies to disease.

As we all know, the whole Covid cavalcade in this country and elsewhere has been ruled by scientific modelling. The mathematics is beyond most people to understand, certainly politicians, and it has been depicted as an integrated component of ‘the science’ that has taken control of our lives. Let’s be clear though. There are light years between the science of predictive modelling and the science of inspired innovation and invention. I am wholly unable to understand why they are classified under the same umbrella title of ‘the science’. They are poles apart. Indeed, and I say this advisedly, there are aspects of ‘modelling’ that veer towards false science – a form of mathematical alchemy and soothsaying cloaked in the language and protocols of science but lacking many of the key criteria of true scientific analysis. The modellers also, and this is crucial, evade the consequences of error and incompetence by blaming everyone else for not doing their bidding or claiming that the alarmist outcome they predicted would occur only didn’t materialise because their sage advice was followed.

You may say the two are closely intertwined and to some extent that is true: the development of a hypothesis and testing to see if it is true, ever searching for the experiment that disproves the hypothesis, moves the theory on to the next stage and higher plain of understanding. That’s one of the principles Karl Popper explained, but it is astonishing how elusive it seems to be for many scientists for whom the hypothesis is treated as true without any empirical verification.

The problem comes when the modelling is treated as the end in itself and is converted into the new truth which everything is believed to be leading towards, regardless of the real world. At that point, the whole basis of scientific principle begins its slow and unedifying collapse, along with society itself. For more than a year now we have been subject to one apocalyptic vision after another, the latest being the truly bizarre projection of a January-style reprise of mass hospitalisations and deaths if we reopen too quickly – or even if we reopen slowly.

Really? In a society with an unprecedented level of vaccinations and involving a respiratory disease in the summer? Surely, an equally plausible model would be the exact reverse? The trouble is that the modellers have already turned their vision of the future into the truth and one which they believe with almost religious fervour, though of course they do not recognise that.

And that is where this obsession with predicting the future, rather than experimenting, turns into a phenomenon with the power to paralyse our society. A year on it’s becoming ever clearer that ‘caution’ is evolving into a blanket suffocating everything that makes us what we are. The mass testing industry reminds me once more of the school environment where everyone involved is there only to serve the ravenous mouth of the data beast: students there to generate data, the staff there to harvest the data and pour it down the gullet into the Machine that spits out the Future.

The truth is that real science involved what would now be described as recklessness. Pliny the Elder, one of the greatest minds the Roman world produced, not only wrote his Natural History in which he explored every phenomenon he could track down from disease to dogs and volcanos to the planet Venus, but also died investigating the eruption of Vesuvius in August AD 79, suffocated by the fumes. How is it that we know we can’t transfuse blood from one species into another? On March 28th, 1667 the maniacs at the Royal Society transfused blood from a sheep into a dog “til the sheep died and the dog well” (John Evelyn, who witnessed the experiment). He added that the results were “ordered to be carefully looked into”. Bonkers perhaps, but an invaluable lesson learned.

Regardless of your views about vaccines, it is a fact that Edward Jenner took the reckless step of infecting his gardener’s eight-year-old son first with cowpox and then with smallpox. As we all know, the experiment was a success. By today’s standards of gibbering caution, it was the most outrageous example of recklessness imaginable. Yet how else was he ever going to find out if it worked? If that happened today, Jenner would probably never have dared try his theory out and if he had he’d have been struck off and imprisoned. I have no doubt that had a predictive modeller been on hand, busy calculating the risk, there wouldn’t have been a virus in hell’s chance of him being allowed to go ahead.

On December 23rd 1750 Benjamin Franklin electrocuted himself when he tried to kill a turkey with electricity, believing the meat would be more tender. He survived, chastened by the experience. In 1839-43, James Clark Ross took two sailing ships, the Erebus and Terror, on an epic voyage of exploration and scientific experiment around Antarctica. Today he wouldn’t have been allowed out of port.

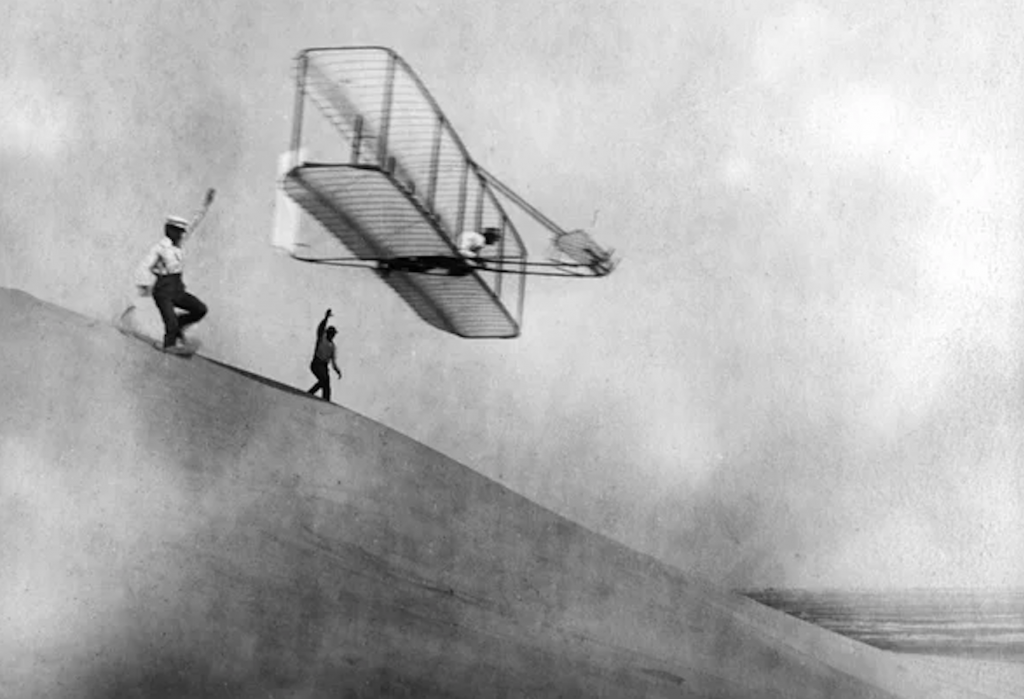

There are so many other examples from those days of early science it would be impossible to list them. But the underlying approach reaches right into more recent times. We have aviation because people were prepared to throw themselves into the air with bizarre pieces of winged equipment or brave their way across the Atlantic in a Vickers Vimy from Newfoundland to Ireland, as Alcock and Brown did in 1919. Imagine the risk assessment if anyone had bothered to think of writing one at the time, and the same applies to Marie Curie’s work on radiation.

The miracle of the Space Shuttle’s glide descent into landing was a triumph of scientific experimentation and research. And yes, it came at a price and it was a price those who flew in it were also prepared to take. Every part of everyone’s lives today has benefited in some way from the innovation and research that humans alone among the living beings on this planet are capable of, and the risks taken along the way.

And yet here we are, 21 years into the 21st century, and I see the world I live in being paralysed by a crippling sense of fear and caution, riding on the back of one-trick, one-message untested modelling. We are all being slowly suffocated. I am not advocating recklessness for the sake of it. Caution and care have their place, but they can’t be the overwhelming principles by which we live to the extent that nothing else can get a leg in. You may be opposed to the vaccines, but it is impossible to deny that they alone represent some sort of imaginative and experimental response to seeing off COVID-19. But the very benefits they were billed to bring are being dismissed in preference to imposing atrophy on all our lives.

The real danger is that everything that made us what we are is in ever more serious jeopardy, driven there by an obsession that we must be directed by those who believe the future is enshrined in and defined by the modelling and risk assessment that lie within their crystal balls, and that armed with this information governments must legislate to control our every action and thought. That path leads to only one destination: oblivion.

I shall now turn to my 1976 Honda CB400F and go for a ride.