A middle-aged woman, walking along a pavement in the afternoon sunshine, sees a young family approaching and instantly becomes stricken with terror at the prospect of contracting a deadly infection. A man in a queue in a garage kiosk leans into the face of another and screams, “You selfish idiot! Hundreds of people will die because you don’t wear a mask.” The aggressor is oblivious to the fact that his victim suffers a history of asthma and anxiety problems. A neighbour puts on a face covering and plastic gloves before wheeling her dustbin to the end of her drive. These are three recent examples of many similar events I’ve observed or read. What could be the main reason for such extraordinary behaviour? Has the emergence of the SARS-COV-2 virus magically re-wired our brains, transforming many of us into vindictive germaphobes?

No, of course not. These extreme human reactions are, I believe, primarily the result of the Government’s deployment of covert psychological ‘nudges’, introduced as a means of increasing people’s compliance with the Covid restrictions.

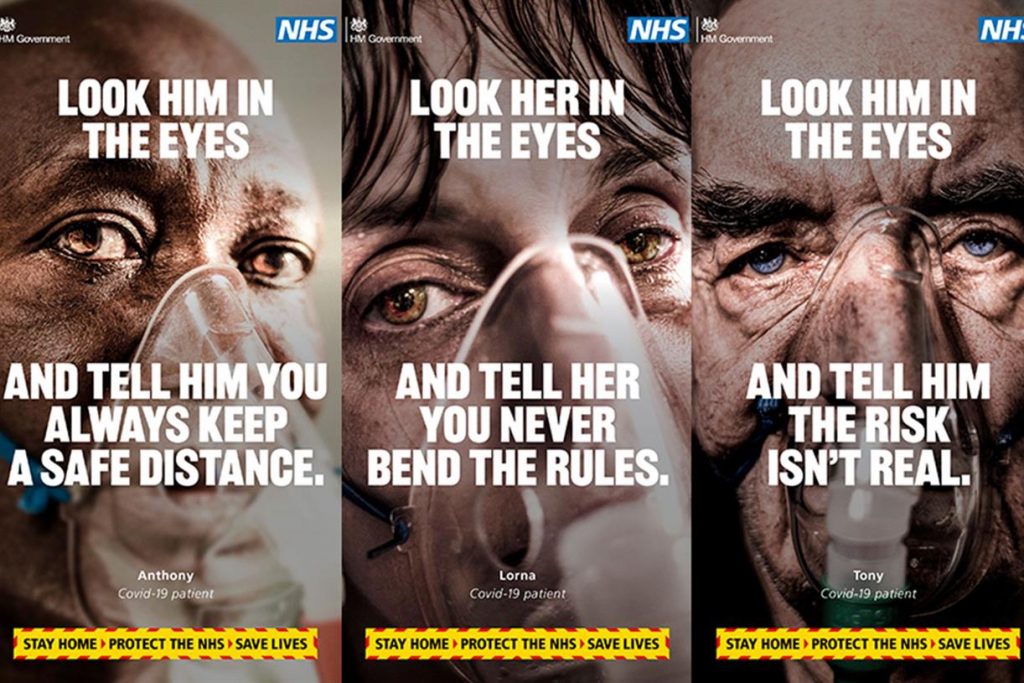

In an article in the Critic, I discussed the remit of the Government’s behavioural scientists in the Scientific Pandemic Insights Group on Behaviours (SPI-B), a subgroup of SAGE which offers advice to the Government about how to maximise the impact of its Covid communications strategy. The methods of influence recommended by the SPI-B are drawn from a range of ‘nudges’ described in the Institute of Government document, MINDSPACE: Influencing behaviour through public policy, several of which primarily act on the subconscious of their targets – the British people – achieving a covert influence on their behaviour. The three ‘nudges’ to have evoked the most controversy, among both psychological practitioners and the general public, are: the strategic use of fear (inflating perceived threat levels); shame (conflating compliance with virtue); and peer pressure (portraying non-compliers as a deviant minority) – or ‘affect’, ‘ego’ and ‘norms’, to use the language of behavioural science. (Specific examples of how each of these covert strategies have been used throughout the Covid crisis are described here).

The British Psychological Society (BPS) is the leading professional body for psychologists in the U.K. According to their website, a central role of the BPS is: “To promote excellence and ethical practice in the science, education and application of the discipline.” In light of this remit, I – together with 46 other psychologists and therapists – wrote a letter to the BPS on January 6th, 2021, expressing our ethical concerns about the use of covert psychological strategies as a means of securing compliance with Covid restrictions. In particular, our alarm centred on three areas: the recommendation of ‘nudges’ that exploit heightened emotional discomfort as a means of securing compliance; implementing potent covert psychological strategies without any effort to gain the informed consent of the British public; and harnessing these interventions for the purpose of achieving adherence to contentious and unevidenced restrictions that infringe basic human rights.

Responses from the BPS to our initial letter were slow and circuitous. However, on July 1st we received an email from Dr. Roger Paxton, the Chair of the Ethics Committee, which clarified the BPS’s position: in the Committee’s view, there is nothing ethically questionable about deploying covert psychological strategies on the British people as a means of increasing compliance with public health restrictions.

An in-depth inspection of Dr. Paxton’s defence of the BPS reveals that it is evasive, disingenuous and wholly unconvincing.

First, he quibbles about the use of the word “covert”, arguing that the compliance techniques under scrutiny are more appropriately described as “indirect”. Behavioural-science documents routinely refer to the psychological strategies underpinning Government communication campaigns as evoking responses from people that are “unconscious”, “subconscious” or “automatic”. The crucial point is that the human targets of these ‘nudges’ are often unaware that the intention of the SPI-B psychologists is to scare, shame them and socially pressure them to conform. The MINDSPACE publication – co-authored by Professor David Halpern, an SPI-B and SAGE member – seems to concur: “Citizens may not fully realise that their behaviour is being changed… Clearly, this opens Government up to charges of manipulation… [as] it may offer little opportunity for citizens to opt-out.” (p. 66)

Second, Dr. Paxton rejects the idea that it would be ethical to offer citizens an opportunity to opt-out by asserting that the application of covert psychological strategies to shape people’s behaviour falls outside the realm of individual consent. The BPS appears to be claiming that an appeal to some nebulous, ideologically-driven concept of social decision-making exempts psychologists from the fundamental requirement to seek a person’s informed agreement before delivering an intervention. So according to the BPS – the formal guardians of ethical practice in the U.K. – the Covid communications strategy, aimed at achieving mass behavioural change, was intended to influence some anonymous collective rather than the actions of as many individuals as possible.

Again, the BPS stance is at odds with Professor Halpern’s position. In his 2019 book, Inside the Nudge Unit, he states: “If Governments… wish to use behavioural insights, they must seek and maintain the permission of the public. Ultimately, you – the public, the citizen – need to decide what the objectives, and limits, of nudging and empirical testing should be.” (p. 375)

Third, Dr. Paxton’s claim that the levels of fear throughout the Covid pandemic were proportionate to the viral threat is ill-informed and does not stand up to scrutiny. The minutes of the SPI-B meeting of March 22nd, 2020, demonstrate that its endorsement of a covert psychological strategy was a calculated decision to scare the British people, recommending that: “The perceived level of personal threat needs to be increased among those who are complacent… using hard-hitting emotional messaging.” In her book, A State of Fear, Laura Dodsworth interviewed members of SPI-B who confirmed that there had been a concerted effort to elevate the fear levels of the general public. One committee member, Educational Psychologist Dr. Gavin Morgan, admitted: “They went overboard with the scary message to get compliance.” Another SPI-B member – who wished to remain anonymous – was even more forthright: “The way we have used fear is dystopian… The use of fear has definitely been ethically questionable. It’s been like a weird experiment. Ultimately, it backfired because people became too scared.”

The mission to indiscriminately instil fear in the British public has been highly effective. An opinion poll prior to ‘Freedom Day’ suggested most people were worried about the prospect of lifting the remaining Covid restrictions. Even now, when all the vulnerable groups have been offered vaccination, many of our citizens remain tormented by ‘Covid Anxiety Syndrome’ – a disabling combination of fear and maladaptive coping strategies – with 20% of the population ‘markedly affected’. And this psychology-assisted fear inflation will be responsible for a substantial proportion of the extensive collateral damage associated with the restrictions, including excess non-Covid deaths and mental health problems.

Fourth, Dr. Paxton’s response makes no reference to the use of shame and scapegoating, and whether these are acceptable strategies for a civilised society to use. One can only assume that the BPS either views these tactics as acceptable, or that they seek to avoid acknowledging that psychologists have recommended practices that, in some respects, resemble the methods used by totalitarian regimes such as China, where the state inflicts pain on a subset of its population in an attempt to eliminate beliefs and behaviour they perceive to be deviant.

The dismissal of our ethical concerns by the BPS was predictable: a cursory glance at the scientists comprising the SPI-B shows that several of its members are also influential figures in the BPS; a major conflict of interest that renders the impartiality of their views highly questionable. What was surprising was the strident tone of Dr. Paxton’s rejoinder, as exemplified by his assertion that the psychologists’ role in the pandemic response demonstrated “social responsibility and the competent and responsible employment of psychological expertise”. I suspect the lady trembling on the pavement, the young man being verbally abused in the garage, and the neighbour donning mask and gloves to wheel out her dustbin – along with the many others in similar positions – might all beg to differ.

Dr. Gary Sidley is a retired NHS Consultant Clinical Psychologist.