by Dr Alan Mordue MB ChB, FFPH (Ret)

During this Covid pandemic I have heard much in the media from ‘public health experts’ and ‘public health officials’, but rarely from colleagues in my own specialty – Public Health! This is very surprising since the specialty, which I practised for 28 years as a Consultant in England and Scotland before my retirement in 2016, usually leads the management of all outbreaks of infectious diseases in the U.K., and also has had the responsibility for leading the production of pandemic plans in the U.K.

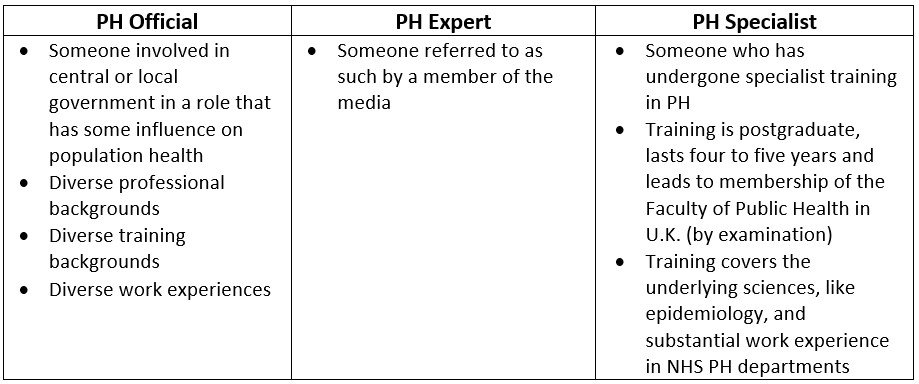

But is there any difference between a Public Health (PH) official, expert and specialist? Certainly you wouldn’t think so listening to most broadcast media. Here are my definitions:

So these three groups are very different. Only one group has undertaken an in-depth specialist training and has theoretical and practical experience in outbreak control and management (as well as other areas of PH specialist practice).

When a PH ‘expert’ expresses views in the media about the management of the Covid pandemic it is therefore essential to know a little about their background training and experience. Even if they have an exalted title like ‘professor’, their chair may be in anthropology or their main experience in nutrition or dentistry. This is not to dismiss the contributions of diverse disciplines – given the inevitable complexity of a national response to a pandemic we certainly need to draw upon a wide range of expertise. However, over the last 18 months I have kept asking myself whether PH Specialist knowledge, skills and experience have had sufficient influence during the Covid pandemic. I will attempt to answer my question by referring to some of the key principles of Public Health and considering whether they have been followed or not during the pandemic response.

1. Ensuring accurate data on health and disease

To study health and disease in populations (epidemiology) the availability of appropriate, timely and accurate data is essential. When managing an infectious disease outbreak one of the first things on the first agenda of any Outbreak Control Team meeting is to agree definitions for possible, probable and confirmed cases. Invariably the latter runs something like this:

Confirmed case: Someone presenting with symptoms of the disease in question with a positive test identifying the presence of the infectious agent.

Either symptoms or a positive test alone is insufficient, both must be present to be counted as a confirmed case. It follows that there is no such thing as an asymptomatic case.

This standard definition was not adopted at the start of the pandemic. Because of this we don’t know how many real cases of COVID-19 we have had or have currently – the numbers recorded include real cases of people with relevant symptoms and a positive PCR test for viral RNA, but also include people with no symptoms of COVID-19 and only a positive PCR test. This has been further complicated by mass population testing in the community and hospitals of those without COVID-19 symptoms, the use of high cycle thresholds in the PCR test, and inevitably large numbers of false positive tests.

This inadequate and inaccurate case definition has also had knock-on effects on the count of COVID-19 hospital admissions each day and current hospital in-patients – with many patients recorded as COVID-19 admissions or in-patients but without COVID-19 disease. Mortality data has also been corrupted by the adoption of a definition of a COVID-19 death as someone who has died within 28 days of a positive PCR test. So someone admitted with severe trauma after a car accident or after a heart attack who tests PCR positive and dies within 28 days is recorded as a COVID-19 death. This definition not only inaccurately attributes a death to COVID-19 but also has corrupted the mortality record for accidents, coronary heart disease and other diseases.

All these issues result in uncertainty about the true impact of COVID-19 and all will exaggerate its apparent impact. Throughout the pandemic there has been further exaggeration as a result of modelling rather than principally relying on real world data (even if it is imperfect). Modellers have produced regular worst case scenarios, that rarely if ever have come to pass, and there has been insufficient scrutiny of the underlying assumptions built into their models. Worse still, the Chairman of the SAGE modelling group has recently admitted on Twitter that their scenarios are developed to support policy rather than the other way around – as Fraser Nelson put it, an example of policy-based evidence-making.

It is abundantly clear that this fundamental principle of Public Health has not been followed during the management of the pandemic.

2. Careful assessment of the evidence for all interventions and their costs and benefits

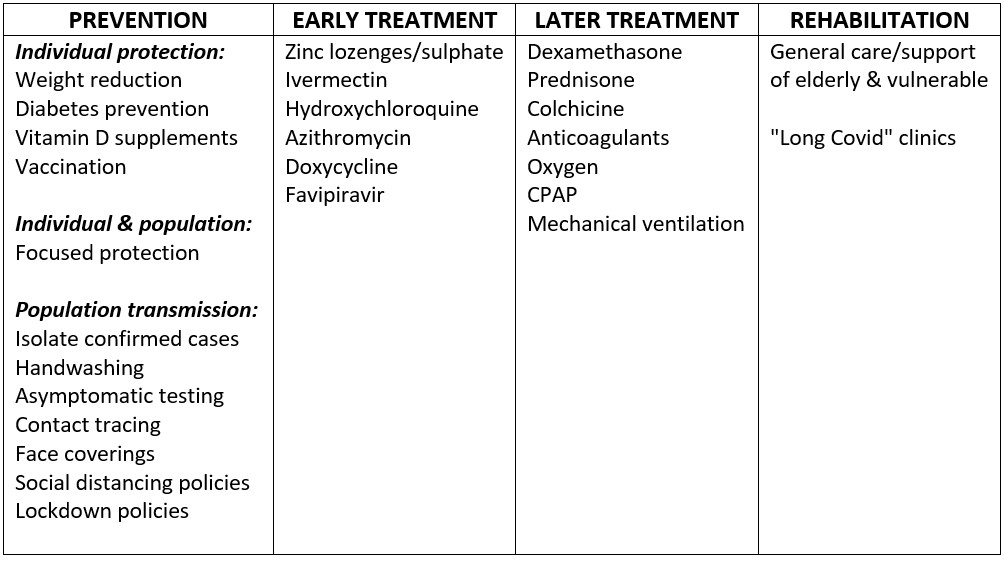

Typically clinical specialties focus their expertise on a narrow range of conditions and treatments. In contrast, PH takes a broader perspective and considers all conditions and a range of potential interventions from prevention, through treatment to rehabilitation. For example, for COVID-19 this could cover:

Usually there would be a careful assessment of the evidence for all interventions – examining the quality and consistency of the evidence, the effect size or impact in terms of both relative and absolute risk, how the ability to benefit and cost effectiveness varies by age/sex/other characteristics, the dis-benefits and side-effects, and finally the cost and opportunity costs. A management plan can then be developed that minimises the health impacts of the disease in question and any dis-benefits or side-effects of the interventions, and is also cost-effective. Inevitably, given the complexity of factors and our imperfect knowledge, decisions on a management plan involve difficult judgements and a degree of subjectivity. Nevertheless, what seems to make sense from a PH perspective, what sort of plan might have been appropriate for COVID-19?

Firstly, in spring 2020, in the face of a looming pandemic with a reported mortality rate of 3-4% (according to the Chinese government at the time), implementing a brief lockdown was understandable – it seemed plausible that it might flatten the epidemic peak, preventing the health service being overwhelmed (as happened in northern Italy), and the Chinese Government said that it worked in Wuhan.

Secondly, being open and honest about the increased risk of serious COVID-19, not only amongst the elderly and those with significant co-morbidities such as diabetes, but also amongst those who were obese would have been helpful. This could have motivated many to lose weight and additional support could have been provided – health benefits would have gone far beyond COVID-19. Next the U.K. population is known to be deficient in Vitamin D, which is known to be an important immune modulator, and there is moderate quality evidence suggesting that doses of over 4000 IU (100 mcg) per day may reduce serious COVID-19 outcomes without any serious side effects. Supplementation for at least those at higher risk seemed sensible.

Thirdly, to reduce population transmission, the standard PH measure of isolation of symptomatic probable and confirmed cases was needed, alongside careful handwashing (although spread via fomites now seems to be less likely). Once the short lockdown was lifted a policy of focused protection of the elderly and those at higher risk because of co-morbidities, as advocated in the Great Barrington Declaration, could have reduced transmission to these vulnerable groups, helped to manage hospital demand, and hopefully reduced mortality. Such an approach was possible because of the steep age stratification of mortality with COVID-19, ten-thousand fold from the youngest to the oldest. This stratification in risk also meant that everyone else could have continued to circulate and lived their lives as normal – keeping society, the education system and the economy functioning, helping to deliver the focused protection policy, and as younger people developed and recovered from COVID-19 population levels of immunity would have improved, further protecting the vulnerable. Such focused protection would have been required until an effective vaccine became available or herd immunity achieved.

Finally, early and later treatment guidelines for COVID-19 based upon the developing knowledge of its pathophysiology were essential, with evaluations of their effect, and if possible randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to improve them over time.

Of course, developing a management plan is much easier with hindsight and when one is not in the eye of the storm. However, by summer 2020 it was clear that something was beginning to go very wrong. By then it was clear from the Diamond Princess and elsewhere that the infection mortality rate was at least an order of magnitude less than the 3-4% we were told by the Chinese. The expectation was also that this was a seasonally driven virus like many respiratory viruses. Yet in early summer 2020 a mask mandate was introduced – despite poor quality evidence that masks could reduce viral transmission, despite estimates of the effect being small, and despite predictable side-effects for individuals and society. Widespread testing of asymptomatic people was increasingly undertaken, rather than the usual approach of only testing those with relevant symptoms, and at great cost. National contact-tracing services were then developed, at a point in the pandemic when the virus was widespread and they therefore had little chance of being effective at limiting transmission, and again at great cost. Bizarrely, early treatment approaches were not encouraged to prevent the development of more serious disease and the need for hospital admission.

Next, social distancing and lockdowns returned in the autumn of 2020. The latter have been described as focused protection of the affluent laptop classes with 10 million essential workers delivering their food, parcels and emptying their bins, despite these workers often being at higher risk from COVID-19. The quality of evidence for the effectiveness of lockdowns was and is poor; their effect size likely to be small, with even many of their advocates suggesting they can do no more than delay COVID-19 illness and deaths; their side-effects predictably immense for population health, the delivery of essential health services to other groups, jobs and the economy, businesses and the very fabric and morale of society; and finally they are eye-wateringly expensive.

Last but not least, COVID-19 vaccines were approved under emergency use authorisation and rolled out through an impressive delivery programme. Evidence for their effectiveness came from RCTs using confirmed cases (symptoms plus positive test) as the main outcome measure, with the numbers involved and the short follow up of only two to three months meaning hospital admissions and deaths were too small to interpret statistically. There was limited short term data on side effects and none whatsoever for longer term side effects. Given these and other limitations, and the precautionary principle and dictum ‘First do no harm’, rollout to only those at highest risk was the obvious sensible policy. However, throughout 2021 the vaccine programme was repeatedly extended to younger and younger age groups despite a progressive fall in their absolute risk from COVID-19 and therefore their ability to derive any benefit, and despite an uncertain and increasingly unfavourable risk-benefit ratio. This was immoral and unethical.

The inevitable conclusion is that the usual Public Health approach to managing infectious disease outbreaks was abandoned in the summer of 2020 – at the time when we knew this was a far less serious disease, when the epidemic peak had passed and the NHS had not been overwhelmed, and when we knew cases would remain low over the summer. Restrictions to basic liberties increased in the autumn without any evidence base and with known huge side-effects and cost. Finally, from December 2020 a mass population-wide intervention programme began and was extended to sections of the population without remotely sufficient evidence on side-effects and unfavourable risk to benefit ratios.

It is abundantly clear that this fundamental principle of Public Health has not been followed during the management of the pandemic.

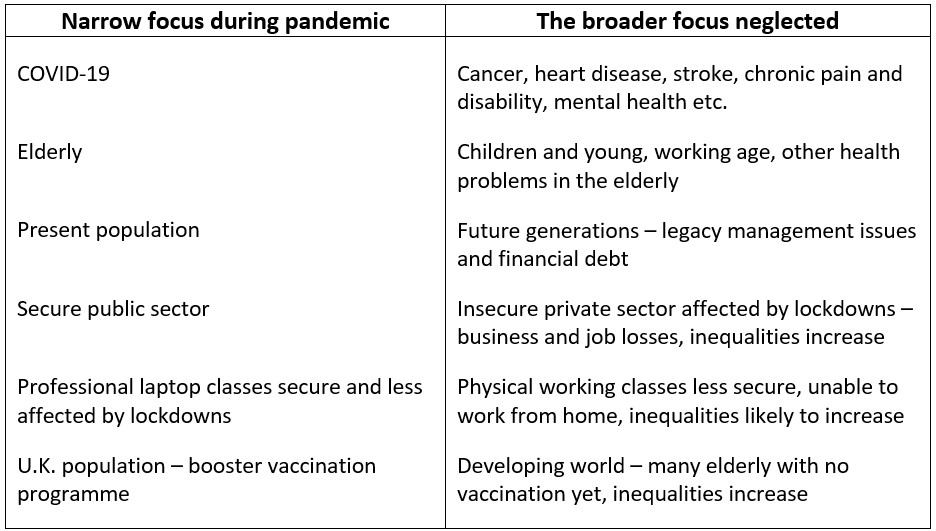

3. Broad focus on the whole population and all health problems

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic the PH precautionary principle has been used to argue for ever greater controls to try to limit transmission and reduce risk to a minimum. However, a unilateral application of this principle to only one disease, that largely affects only one demographic, leads to hugely negative consequences for other diseases and people.

The young have particularly suffered, in terms of their education, health and social well-being. But so too have those with undetected cancer as screening programmes have stopped, those who have died at home rather than access urgent hospital care (excess deaths from summer 2020), and millions whose chronic conditions have been allowed to deteriorate without proper medical care, resulting in a huge backlog for hip replacements and other essential treatments.

It is abundantly clear that the management of the pandemic has not been proportionate or sensitive to a broad range of needs – this fundamental principle of Public Health has not been followed.

4. Providing accurate information to the public and avoiding unnecessary alarm

Much of this topic has already been covered – inaccurate data on cases, hospitalisations and deaths; lack of information on risk of obesity; modelling extreme scenarios that amounts to policy-based evidence-making; inaccurate reporting of evidence on effectiveness of masks and lockdowns; and inaccurate reporting of risks of side-effects of vaccines and risk-benefit ratios. However, there have also been repeated selective presentations of data in media briefings by PH ‘officials’ and most recently the statement from the CMO for England when talking about the Omicron variant that “… all the things that we do know, are bad”, despite all the experience and reports from South Africa pointing to the fact that it is milder than the Delta variant with far lower hospitalisation rates and deaths.

As for avoiding unnecessary alarm – the SPI-B sub-group of SAGE has deliberately sought to heighten fear and alarm as a means of driving compliance with COVID-19 measures. Whilst there have been some attempts to do this in the past to discourage smoking and improve compliance with measures to combat AIDS, they have been controversial and criticised, and neither of these were anywhere near as systematic, relentless and so well-funded. Laura Dodsworth’s book A State of Fear describes the development and impact of this sinister manipulation of public fear and alarm.

It is abundantly clear that this fundamental principle of Public Health has not been followed during the management of the pandemic – in terms of both accuracy of information and avoiding unnecessary alarm.

Conclusions

This COVID-19 pandemic has been handled in a totally different way to the usual way we manage infectious disease outbreaks and pandemics. All the fundamental Public Health principles considered above have been violated.

Why has this happened? At least some of the major U.K. (if not Scottish) PH ‘officials’ driving the pandemic response have some relevant PH Specialist training and there are PH Specialist voices on SAGE, the new U.K. Health Security Agency and PH Scotland. Perhaps they lost perspective in the face of a global pandemic or were not strong enough to change direction with a relentless and hostile media on their heels.

Whatever the reason, in my view what has happened amounts to a betrayal of the Specialty of Public Health and all the principles and values it used to stand for; and a betrayal of the Public’s Health, in other words the health of the population. The excess non-Covid deaths we have seen so far, I fear, is just the beginning. What mystifies me is why my former colleagues and the U.K. professional body charged with developing and maintaining standards in the PH Specialty, namely the Faculty of Public Health, have been so quiet thorough the whole of this pandemic.

Dr Alan Mordue MB ChB, FFPH (Ret) is a retired Consultant in Public Health Medicine. He worked as a consultant in England and then in Scotland for 28 years, retiring in 2016. He has extensive experience of teaching and training in Public Health and was an Honorary Clinical Senior Lecturer at the University of Edinburgh for many years.