by Dr. Sinéad Murphy

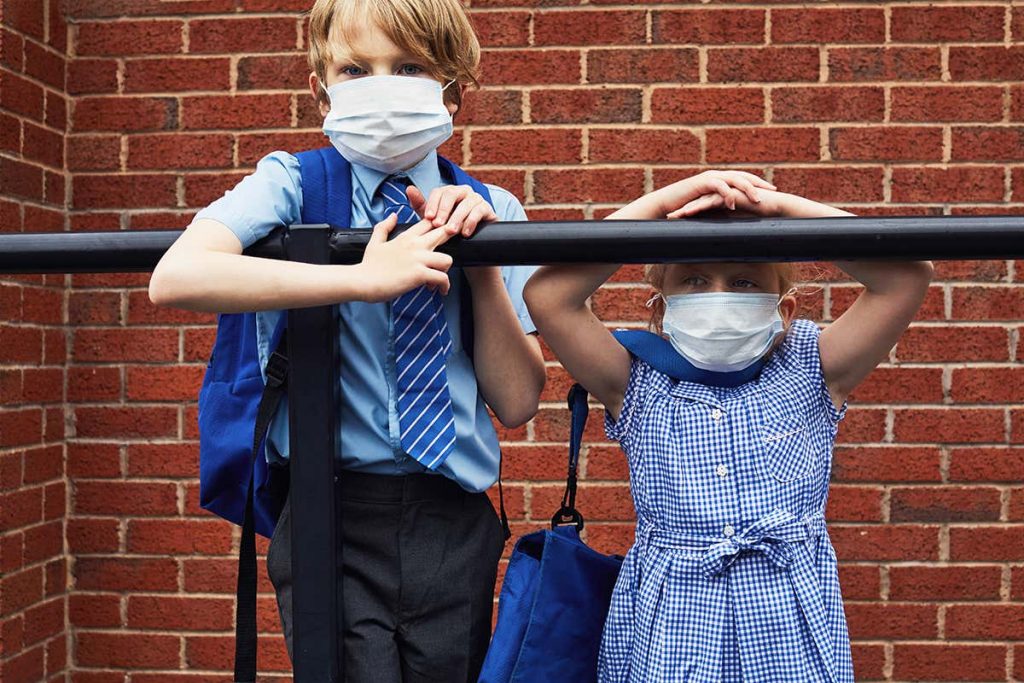

Students spilling out of one of the large secondary schools in Newcastle are all wearing masks again. Evidently, that school at least has revived its requirement for masking, on account of rising ‘case’ numbers among teenagers in the city.

And worse: the BBC reported that on September 30th as many as 2.5% of those enrolled at English state schools were exiled from school altogether for reasons to do with Covid.

The ease with which schools are reverting to covering children’s faces and excluding those who ‘test positive for Covid’ (an entirely unscientific description) makes one wonder whether there is an affinity between our institutions of education and the masking and distancing of the Covid era.

Covid is not responsible for everything that it has exacerbated. Measures taken by schools against it have certainly diminished the personal and palpable content of children’s lives – people in masks might as well be anyone, and nothing on a screen offers much of sensory stimulation. But is neglect of the personal and palpable in fact a general principle of our schools? Is this what explains their complacent revival of masked and remote learning?

* * *

After one-and-a-half years of almost no school at all, our little boy with autism is now attending for three days in the week. We have two reasons for his reduced take-up.

First, the support teacher with whom Joseph has a good relationship, who knows him well and can communicate with him and cares about him, works at the school for three days every week, the same three days on which we are choosing to send him in.

Second, Joseph can only really learn from what is in the world, to be touched and smelt and tasted and heard and seen; the understanding that he gains during the two days in the week on which he accompanies me to the supermarket and the swimming pool, and makes shopping lists and kneads bread and goes to the door to pick up the mail, is not achieved by the most inventive of institutional strategies.

But in the meeting at Joseph’s school at which the new arrangement for his attendance was discussed, it was evident that the real justifications for it were not admissible.

Schools cannot allow that one teacher might be more appropriate than another – the ‘role’ is all, and anyone should be able to play it. And schools cannot accept that there is a possibility for involvement in the world that none of their representations of it and none of their simulations of it can ever hope to match for enlivenment of body and mind.

Last year, during the few weeks that Joseph could be at school, we kept him at home on days when his support teacher was unable to be there. It was made clear at the meeting that this personal arrangement would no longer be encouraged, that a new appointment was about to be made of a teacher trained in the support of children with special needs who would shadow Joseph’s teacher and be ready to step in for her in the event of absence.

And when I attempted to explain how quickly and well Joseph learns from moving about with purpose in the world, I was asked whether it would be possible for me to take Joseph to a museum or a gallery during our home-schooling days, as that would provide excellent documentary evidence that ‘off-site’ learning really was taking place.

So little do our schools place any value on the personal that a total stranger, with no understanding of Joseph’s idiosyncrasies and with no care for him at all, is judged as the equivalent of a woman who has known and liked him for three years.

And so little do our schools place any value on the palpable that the best substitute that they can find for themselves is another institution in which the experiences available are plucked from life and suspended in space and time for contemplation at a distance.

Small wonder that the masks are taken up so very easily when teaching and learning are not supposed to be personal anyway, and small wonder that everything switches to remote so very smoothly when the museum and the gallery are what count as the optimal ‘off-site’ learning environment.

* * *

But children with autism are a special case, we might think; their requirement for personal attention and palpable experience is part of their specific disability.

Is this true? Or is the intolerance of anonymity and of abstraction that defines autism in fact manifest in many who manage to pass muster at school and elsewhere?

Almost pass muster, at any rate. The NHS website includes descriptions of two conditions that are reported to be on the rise among young people in the U.K.: ‘depersonalisation’ and ‘derealisation’, which are disorders comprised of just that craving for the personal and the palpable that characterises those with a diagnosis of autism.

‘Depersonalisation’ and ‘derealisation’ are judged as ‘mental health’ issues, often subject to pharmaceutical treatments. But are they really ‘mental health’ issues, or are they entirely human responses of anxiety and disaffection in the face of ever-increasing anonymity and abstraction?

If they are such human responses, then schools’ active disregard for the personal and palpable is contributing significantly to their concerning increase, which increase must surely be partly responsible for the growing number of children being referred for diagnoses of autism.

The question arises, then, as to whether our schools are at least contributing to driving our children onto the ‘spectrum’?

It is a drastic allegation. But then, these are drastic times. And our children are coping with a drastic diminution of what may reasonably be regarded as the fundamentals of human life: the personal and the palpable, other people and the world.

* * *

It is an established philosophical theme: that human beings are irreducibly situated; that there is no baseline human life which is then overlain with circumstantial content; that human life is circumstanced all the way down.

Martin Heidegger summarized this view by defining human being as “Dasein” and “Mitsein” – being-there and being-with. What makes human life human, for Heidegger, is the dual fact of that life being always in a world with which our bodies are woven and always with others with whom our understanding is given and built up through interaction.

“Dasein” and “Mitsein” are abstract terms, as are ‘being-there’ and ‘being-with’. But what Heidegger intended to communicate with them was not so much that human life is in a world with others, but that our lives are in this world with these others. The claim is an existential one and not merely philosophical. Our human lives are personal, Heidegger meant. And our human world is palpable.

If Heidegger was right, then any erosion of the personal and the palpable is an erosion, not of the variety of life nor of the joy of life but of the humanness of life. For, to be human is to be there in a world that can be touched and tasted; and to be human is to be with people we know and understand and love.

Those who are not appalled at schools’ masking and distancing of children may assume that we can be with masked others and there in a remote world. Against this assumption, we can only appeal that it is less isolating even to be alone than it is to be surrounded by a sea of masked faces, and less awful even to be in a strange place than it is to be screened off and at a distance.

In favour of this appeal, we can point to the rise in diagnoses of ‘depersonalisation’ and ‘derealisation’ in our young people, together with the rise in their medication – prescriptions for anti-depressant medicines for those under 17 hit an all-time high during 2020, up 40% from five years before.

* * *

When Dickens’s Paul Dombey – pale and slight and destined to an early grave – first arrives at the boarding school to which his misguided father has sent him, he is left waiting in the study for someone to show him to his quarters. Weary and forlorn, with an aching void in his little heart, Paul is described as feeling as if he had taken life unfurnished and the upholsterer were never coming.

It is an affecting scene, of abandonment to a world without familiar sights and sounds and smells, peopled with strangers whose faces are not known.

I think that children with autism often feel like little Paul (who, as it happens, does not socialise normally with other children and is described by other characters as ‘old fashioned’). They feel as if life is bereft of what is really meaningful: of daily routines that are not to be departed from and that are entered into by all around; of familiar enduring objects; and of the faces of those whom they understand and who understand them. It is why they are drawn to small corners, why they clamber to sit behind you on your chair so as to be cushioned tightly between a warm person and a supporting world – one of Joseph’s very first words was ‘cozy’.

The responsibility of those of us who care for children with autism is to try to make them more cozy: to gather around them as much of meaning as we can; to furnish them with personal and palpable content; to establish routines and interact with objects and befriend people so as to thicken their being-there and being-with – to be the upholsterers of their lives.

But all children need what children with autism demand. All children feel ‘depersonalised’ when there are not people around them who really care, and all children feel ‘derealised’ when the world does not stimulate their senses. All children wish that the upholsterer would come.

Instead, what are we doing? We are doing the very opposite, stripping our children’s lives of what scanty furnishings remain to them. What people they have around, we are masking. What world there is left to touch and taste and smell, we are screening off. We are turning their young hearts into aching voids, with all outside so cold, and bare, and strange.

There is a medical experiment currently unfolding in schools, on account of which we ought to feel grave concern.

But there is an existential experiment unfolding there too, an experiment in removing the human content from the youngest human lives, as if they had taken childhood unfurnished and have no chance of cozy at all.

Dr. Sinead Murphy is an Associate Researcher in Philosophy at Newcastle University.