Radio 4’s Today programme had an item on Saturday 12th April 2025 (you can listen to it here; wind forward to 01:53:20) about its Book Club, specifically focusing on what it called “books for boys aged between 12 and 14” with Anthony Horowitz and Charlie Higson.

What followed could not have better illustrated the gulf between my own boyhood and the lives of boys today. One mother told the programme that her 12 year-old son liked the Wimpy Kid books (whatever they are) and she was struggling to find anything else for him that was “funny”.

I was born in 1957. By the time I was literate in the early 1960s I was reading voraciously, unsurprisingly beginning mainly with Enid Blyton and then advancing to CS Lewis, whose allegorical messages were entirely lost on me. But I soon gravitated to something much more thrilling.

All these years on I cannot remember quite when I first picked up Reach for the Sky (1954) by Paul Brickhill (1916-91). What I do know is that I could not put it down.

Reach for the Sky was the biography of Douglas Bader CBE DFC DSO (1910-82), the RAF pilot who famously lost both his legs during reckless aerobatics in 1931. Despite his relentless and ultimately successful determination that he would learn to walk again on the primitive artificial limbs of the era, he was discharged from the RAF.

But when the Second World War broke out, the frustrated Bader spotted an opportunity. With brute force of will, he succeeded in rejoining the RAF. He fought during the Battle of Britain and was shot down in August 1941, probably by friendly fire, and was incarcerated for the rest of the war. During that time Bader ended up in Colditz, the prisoner-of-war camp reserved for the most troublesome.

Today Bader is often seen in a less flattering light, not least for his air warfare strategy known as the ‘Big Wing’ and unedifying aspects of his personality. But to me aged 10 or 12, I was completely galvanized by his utterly heroic insistence on fighting back against his disability rather than turning it into a meal ticket.

Of course, the war provided Bader with a fabulous opportunity, but that only made me feel more inspired by what he and others did. I was flung into a world that every adult I knew had experienced in some form. There were still undeveloped bomb sites in London, so I knew it was all for real.

It wasn’t until many years later when at sixth form in 1976 I discovered that Pat Reid MBE MC (1910-90) had been an old boy of the school. Reid was another famous guest of the Third Reich at Colditz and had escaped. His books about Colditz had inspired the famous BBC television dramatization. He turned up at the school’s annual fête, sitting at a desk in the summer sunshine signing copies of his first book, The Colditz Story (1952), which had been republished.

I’ve still got my copy, a treasured possession, and I’ll never forget looking into the face of the man who by then was almost exactly my present age but who had led a life beyond my imagination.

There were plenty of other such books. Paul Brickhill, who I might point out was the ‘real thing’ (he had been a fighter pilot and prisoner of war himself), also produced The Great Escape (1950), another exhilarating tale of staggering heroism, resilience, and ingenuity now almost entirely known only from the movie version.

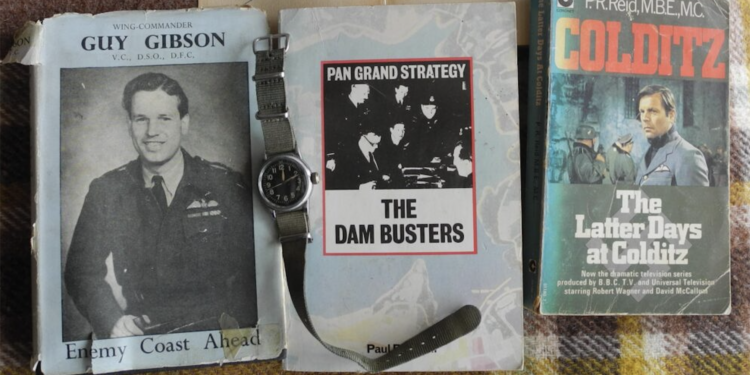

Brickhill’s The Dam Busters (1951) was no less of a thrill and introduced me to the breathtaking bravery of the boys of Bomber Command and the capabilities of the Lancaster. My mother never stopped reminding me that I shared a first name with 617 Squadron’s CO and the leader of the Dams raid of May 1943, Wing Commander Guy Gibson VC (1918-44).

Gibson’s one and only book Enemy Coast Ahead (1944) is one of the most rightly celebrated personal accounts of the air war, especially his recollection of the bouncing bomb and the dams. Gibson, as is now well known, was an elitist and in many ways an unpleasant individual. But no one could doubt his courage and skill.

The list goes on. I worked my way through Cornelius Ryan’s The Longest Day (1959) about D-Day, and his A Bridge Too Far (1974). Gratifyingly, many of these books were turned into films, evoking a strong sense of the time. CS Forester’s The Last Nine Days of the Bismarck (1959) was made into Sink the Bismarck the following year.

I saw the film aged 12 at the school film society with hundreds of other boys, all jammed into the school hall with our satchels and coats since it was shown after lessons had ended. We sat there transfixed with excitement. I watched it again only the other day and I was astonished at how well it had held up over more than 60 years.

It is wholly unimaginable that today any school would even mention Sink the Bismarck, let alone show the movie. And even if it did, there’d have to be letters to parents, advance warnings, and then counselling for the distress caused afterwards. No doubt it would have to be sandwiched between marathon viewings of Adolescence.

All we did back then in 1969 was cheer. It was incredibly exciting, but the terrible and tragic sight of HMS Hood being atomized and lost with all hands bar three when it was hit in its magazines by Bismarck will stay with me forever.

Every adult I knew in those days had experienced the Second World War, including my teachers, even if only as children. This was so everyday a fact it was easy to forget, but not on one afternoon in 1967. Our English teacher, Sammy Thurlow, looked so old and decrepit that it would have been easy to believe he was 90, at least to a boy of 10. He was in fact about 50. He shook the whole time. He was a kind man and had set us an essay on the subject of “fear”. I recall with complete clarity that he stood in front of me and said, “I hope you never know the real meaning of fear.”

It was not until later that I discovered he had been in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp and had been tortured. He of course never mentioned it.

The books I read as a boy were for real. These were real events involving real men, not the glamorised violence of Bond. The Second World War was a terrifyingly appalling time and involved some of the greatest recorded barbarities in world history, so I am not glorifying that.

What I am remembering here is that for me, at least as a boy, these books also gave me the opportunity to admire the achievements of a previous generation which, when faced with terrible adversity, stood up and faced it. We should never be ashamed of men like Bader, Gibson, and Reid, or all the others who did things we will never be called on to do ourselves.

In later life I was fortunate enough to know several men who were pilots with Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain. I made sure my four sons met those men, and they still remember the experience of doing so today.

One of them was the ace Allan Wright DFC AFC (1920-2015) of 92 (East India) SQ whom I met on a 1999 Time Team shoot to dig up one of the squadron’s Spitfires (P9373), shot down on May 23rd 1940 near Wierre-Effroy in northern France. The pilot, Sgt Paul Klipsch, had been killed. Allan, who had test-flown the Spitfire when it was new to the squadron, was an intensely modest man who refused to write up his memoirs. He told me he used to hide in the toilets at Biggin Hill in the evening, trying to recover from the trials of every day in summer and autumn of 1940 when he was fighting for his life and his country.

In an incredible development, the Spitfire’s wreckage contained maps belonging to Roger Bushell (1910-44), squadron leader of 92 SQ, who was also shot down that day. He and Klipsch must have swapped aircrafts. Bushell was the man who led the Great Escape from Stalag Luft III and was executed, along with his escape partner Bernard Scheidhauer, by the Gestapo after being recaptured. Fifty more recaptured escapees were murdered on Hitler’s orders.

And then there was my late father-in-law Adrian Carey, who was a navigator with HM Royal Navy. We still have his Bible, stained with the fuel oil that burst out when his ship, HMS Liverpool, was torpedoed off Malta by the Italians on June 14th 1942. The ship survived, and so did he – luckily for my wife, children, and grandchildren.

As a schoolboy I joined the Combined Cadet Force in 1973 and flew RAF Chipmunks. At the age of 40 I learned to fly at Biggin Hill myself. In the years following I had the enormous privilege of flying in a B-17G Fortress (in fact the very aircraft that 12 years later crashed and burned out in 2019 in Connecticut), a B-24 Liberator, and a P-51 Mustang in the United States. I did so because of the books I’d read as a kid. And my everyday watch? A US Army Air Force A-11 navigation watch from 1944. Over 80 years old and still ticking – so long as I wind it up.

As it happens, I was wearing it once in Zion National Park in Utah when an American woman recognized it as the same type as her father’s. She stopped me and told me his story of flying Liberators of the Eighth Air Force out of East Anglia.

So for me, all those better-known heroes of the war, like Bader and Gibson, stand for countless other men like Allan or my father-in-law whose stories will never be told in detail. We should all be aware of what would have happened if there hadn’t been men like them prepared to stand up and fight during those dark days. Richard Dimbleby’s celebrated and horrific account of the camp at Belsen is a graphic reminder of the impact that uncovering the horrors of the Nazi regime inflicted on those Allied forces confronted with them.

It’s quite something to look at some young men today and their disillusion, resentment, and lack of direction. Every way they turn, they are told, or it is implied, that they are deficient in some way and carry a form of original sin they cannot expiate – merely for being male. I taught in a girls’ school for nine years and, by contrast, it’s implied all the time that they are entitled to privilege and advancement, and that anything they do is worthy of admiration – merely for being female.

Yet in 1940, aged 22, Allan Wright got up every morning at the crack of dawn to hold off the Luftwaffe hordes in the Battle of Britain while his young wife tried to make a home for the couple. A few years later, Pat Reid and the other prisoners in Colditz were devising ingenious escape plans and creating maps, clothing, and equipment out of the miserable resources they had to hand. In 1944 Guy Gibson was already dead, along with hundreds of thousands of others who lost their lives in that epic conflict.

Back when I was a child, I never felt that I should apologise for being a boy and no one ever told me I ought to feel guilty about it. I’m extremely glad I have never had to fight in a war and that none of my sons have. But I’m also extremely glad I had those books to read about men whose courage and fortitude are, or ought to be, a beacon of inspiration. No work of fiction could ever compare, especially ones about ‘wimpy kids’, wizards, and juvenile James Bonds.

The world has moved on, of course, for good and ill. I doubt very much whether the Today programme’s Book Club or any school would ever recommend Reach for the Sky or The Great Escape for boys aged 12 to 14. More’s the pity.

Guy de la Bédoyère is a historian and writer with numerous books to his credit, among them several on the correspondence and writings of John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Boys own stuff, loved this piece, well done Guy

I was born in ’56 and during my childhood I read many of the same books. Later I read ‘Devil’s Guard’; possibly fiction and possibly not, but interesting nonetheless. Enjoyed the article very much, it took me back a long way. I understand now that many of the people were not the nicest people but that in no way detracts from the heroism.

I can say with all honesty that I read all the books mentioned and had similar feelings of awe and fascination at the accomplishments of the war generation. Without them we would not be here. As Guy surreptitiously suggests though these people were brought up with pride and respect for their country. Where has that gone since Maggie left us? All but destroyed by virtually every Prime Minister and politician since, every treasonous one of them.

England, my England.

Snap. I’m a few years younger, but dad was relatively old in those days, and he was involved in various RAF matters in WW2.

Incidentally, the PoW in Colditz is a tourist museum now. I’ve been there as a tourist with some friends on a day trip out from Leipzig in a rented car. One of them, Hans, was brought up in Leipzig, but was one of the emigrants from East Germany, and eventually moved to England.

My old headmaster in the early 60s was ‘old school’ and left the Army as a Major just after the war, When I plucked up sufficient courage to quiz him on why he left a promising military career, (for which he was admirably suited), he replied “I didn’t like it when they told me to stop shooting Italians and took my pistol from me”. Any way, I coughed up some spondulicks to DS simply to be able to comment on your excellent post. Taking the the Queen’s shilling in ’69, I can identify with much of the content of your moving/memory jogging/salutary post. Well done Guy and thank you. I read most of the works to which you refer in my teens and early 20s, but a later read I found particularly moving was by Geoffrey Wellum, entitled ‘First Light’. Joining the RAF at 17, he flew Spitfires in the Battle of Britain and was all-but burnt out by age 21. His biography was written some 60 years later, but is no less moving for that. I commend it to you. I think you’d enjoy reading it,

Having been born just after the war, the signs were all around. At public school most of the more senior masters had been officers, and at my prep school the headmaster had been an officer in the RAF in the Far East and 2 of the old teachers had served in the Ist World War the Maths teacher had been an officer in the RA and the French had been in the trenches. When I started work in the City in the 1970s it was standard that anyone of a certain age had been in the forces

When I entered the corporate world in the early 1980’s, our unit was a “Division” and my job title included the word “Officer”. Awareness of the War was taken as read, and military throwaway lines abounded – Time spent on reconnaissance was never wasted.

New titles all round into the 1990’s, and when older colleagues retired, the generation after mine had been too young for the war literature cited in the article. Time spent mentioning time spent on reconnaissance was inevitably wasted.

Meanwhile the first 20something years of my life had earlier overlapped with the last 20something years of the Grandad conscripted A1 to serve in The War To End All Wars, who thankfuly returned battered but intact to The Land Fit For Heroes To Live In.

The 1890’s were a dangerous decade to be born. In comparison, the 1950’s were a doddle. Whatever the era, “We sleep soundly in our beds because rough men stand ready in the night to visit violence on those who would do us harm.”

Just william, and later biggles biggles biggles in those days they had them in the school library.

I too read the dam busters at least 3 or 4 times, quite superb.

Wonderful article , thank you.

When I lived in England in the mid 70’s our milkman was a former German POW. We have a german last name and would chat with us, my brother and me about what lead to his internment in a British POW camp.How his unit got run over after D-day. He was more than happy to lay his arms down. He said he was done fighting and would rather spend the rest of the war in a camp. He was more read on books than the other men in his unit, including the officers, he said. He loved Democracy. He married, had a great life after the war.

We need to set up boys clubs and teach them their people’s history, and that as men they are something special. And to ignore feminists and woke communist hate speech against them and their sex.

Boys and men make the world work. Without us women would die very quickly.

And without us you wouldn’t even exist. Stalemate.

Truth to misogynists is like sunlight to

: seriously inconvenient, and so best avoided at all costs.

: seriously inconvenient, and so best avoided at all costs.

For me it was Biggles books that got me reading.

Decades later I watched many history and archeology series on TV, and often bought the associated books. But can you imagine the BBC doing a series on British history now? I shudder at the thought of what it would contain. Archaeology is way too white, and don’t even mention the Anglo-Saxons.

For ‘lives of boys today’ change this to be ‘lives of boys today in the English speaking democracies’. Move out of this zone and the phenomenon rapidly drops. Leave Western Europe and North America altogether and the phenomenon is near non-existent. My experiences while working in eg Asia-Pacific have been that most there view what is going on in Britain, Canada, New Zealand… as a total joke. Also, the only countries in which I encounter garbage about ‘white privilege’ are those within the English speaking democracies. In a thirty year, international, career with a high proportion in Asia, Middle East, and some in South America, I have hardly ever encountered statements about ‘white privilege’ in these regions. The British establishment has so marginalised boys of white ethnicity that many would now be better off working in another country of mainly none white ethnicity and my guess is that ever more are going to do precisely this, especially the most able ones. Somewhat ironic but we should not be surprised.

Similar age. I read all of those, and more, as my passion for military matters grew.

Dad was a Lancaster pilot with 582 Pathfinders Sqn. When Thunderbirds appeared in 1966, that was it. Completely hooked and initiated a 42 year career in defence aerospace.

Having worked on most platforms, now retired, the passion manifests itself in flight sim, flying what dad flew. I recently built a 3D version of RAF Little Staughton where he was based.

Thanks Dad.

My 8 yr old grandson is intrigued by prison escapes, daredevil pranks and wartime bravery. We started with Papillon and re enacted all his escapes including his stay with the Indians using toys and props I fashioned out of bits and pieces. Then he discovered Douglas Bader and I sorted him a pilot outfit for World Book Day. His dad had introduced him to Reach for the Sky as he was already intrigued by WW2 and the RAF. Then we moved on to the Great Escape and I’ve made him a replica prison camp from cardboard, netting etc so we reenact it with plenty of improvisation. Now he’s just discovered Biggles and so it goes on….. plenty of fun for me too!

C S Lewis, like Tolkien, disliked allegory. Tolkien denied that the ring in his famous story was meant to be an allegory of the atom bomb. Read as allegory, these stories are likely to be misunderstood.

Lewis’s Narnia stories present the girl and boy characters in it to the child reader as exemplars, but not quite as might be expected. In the service of Aslan, Susan doesn’t become like a woman joining the WRAF in 1939 or QMAAC in 1917. Subsequently, on growing up under a particular malevolent influence she ceases to like bows an arrows, exchanging them for lipstick and nylons.

There is one great disadvantage in all these books that the author mentions here.

Focusing on exploits of individuals, they tell the reader nothing about Britain’s involvement in the Second World War. The subjects do not tell the reader what they thought or felt, say, in 1939. Vera Brittain’s autobiography is deficient in the same way; making it much less of a testament to youth than that of her contemporary, the poet May Wedderburn Cannan’s Grey Ghosts and Voices.

There are lots of other books of similar types to Reach for the Sky. I Was Monty’s Double, made into a film which had to be embellished with fictional action scenes to alleviate the tedium. And though fictional, The Cruel Sea, is more successful in presenting the horror and human cost of war; war being performed as simply a task that must be done once it is given to the actors to do.

Battle over Britain by Francis K Mason is a magnificent example of detail, researched and arranged with love, probably never to be surpassed, often mentioning individuals by name who will never have complete books written by or about them.

However, this book being in diary form, it suffers from the same problem of lacking any wider context. Day follows day without any indication of what each action meant. No doubt how each person experienced these days at the time, but leaving behind no imprint of meaning. What was the point of the death of an RAF pilot when his Spitfire crashed into the Solent? His book ends at that chapter.

No one among the public celebrates Waterloo Day anymore. There are veterans who have become fixed in their identity by their involvement in the Second World War, as if nothing happened to them before or since. One lives to reach a 100 while his colleagues died aged 20; but both forever fixed in their wartime identity. Is this a mountaintop that we should all set up our tents on? It is possible to become morally damaged by wars we never fought in.

All these books that the author mentions were really written and read by people, those who had endured the Second World War, as a form of catharsis. The Man Who Never Was, especially in its first film adaptation, is a salient example of this. An imprint of meaning is left behind on all those survivors who, burying their beloved dead in their hearts, lived because they had died to make it so. Today, a lifetime later, this healing is not a salve for our condition.

A fine comment although I believe you have narrowed the subject. For some, like me a Patriot the histories of our 20th century wars reflect the goodness, resolution, passion and bravery of the people of these islands when properly led. And in many cases singular events in our lives do define those lives. I see nothing negative in looking backwards.

Thank you Guy very thoughtfully put together. My father was also a Japanese POW. He spent three and a half years in Changi which included a trip up to Ban Pong to help with the Japanese government’s railroad project. He came back in September 1945 weighing 6 1/2 stone suffering from Beri beri and malaria. He never ever spoke about his experiences apart from the fact that when his ship docked at Liverpool the dockers were on strike and refused to help unload their equipment. As a result he acquired an inherent dislike of Trade Unions. Always a hero in my book.

My uncle was a Pathfinder, but of course I knew little about it until I read Guy Gibson’s book (my mother, his sister, had a lot of books on the RAF).

I had no idea Gibson was an unpleasant individual, but his paragraph on the last page is most telling: “People will forget and this will happen again”.

Prophetic? His generation would be utterly appalled at what is happening now – I know for sure that my father, who was in the army, would have been utterly disgusted. By the way, he used to say that Tony Blair was the second worst PM after Harold Wilson. Goodness knows what he would have made of May and Johnson, never mind Starmer.

When younger, I had watched the Dambusters film with Richard Todd many times. My Father and Mother were both RAF during the war, RAF Military Police/Quartermasters Sergeant. So it always carried a bit more weight.

Not till later did I come to appreciate that Gibson was a Wing Commander, and flew the Dams mission at the tender age of 23. The appearance of Richard Todd made him look like he was a seasoned thirty something. 23..! to hold that rank, to fly that plane in combat conditions, to show such heroism and leadership. It is mindboggling. Yet I suppose there were dozens of Guy Gibsons, not all as famous and recognised, but they led the line to defeat the Nazi’s. We should be immensely proud of him and those like him, even his dog ‘Trigger’.

Of Gibson, I was going to say ‘don’t mention the dog’. Sad to watch a censored version of The Dambusters.

Thought provoking article – thank you.

Born in ‘53 I grew up reading these books. Many of my teachers had served in the war.

I’m remembering a teacher at my school who was a Japanese POW on the Burma Road. When the school band, which I played in. played the Last Post on Remembrance Days he would weep.

How banal life has become in my lifetime.