Sometimes, an event can be important both in terms of its immediate consequences and as a harbinger of what is to come. The passage to the committee stage of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill here in the U.K. last Friday is one such event.

The Bill, if it becomes law – which now seems likely – will legalise ‘assisted dying’ along the lines of Canada, the Netherlands, and so forth in the U.K., and thereby bring us to liberalism’s very zenith. Here, the final promise of the liberal polity – that the state exists to liberate all individuals equally and totally, even in respect of the manner in which they die and the timing of their deaths – will be realised. The Bill is therefore naturally going to have radical consequences for people who fall under its application, but it is also indicative of something truly epochal – the final unmooring of liberalism from religious constraint, such that its true nature will be revealed as it floats untethered into the heavens.

It is important to be clear about the import of this. So-called ‘slippery slope’ arguments are familiar in respect of debates about assisted dying, and plenty of them were made in the House of Commons in the debate last week. Typically, we imagine said slope ending somewhere undesirable, but recognisable – the scenario most often depicted by those opposed to assisted dying is that of the elderly or terminally ill person feeling pressurised into taking his or her own life so as not to be a ‘burden’ on loved ones (or the health service).

But we will learn in the coming decades that the slope extends much more steeply downwards beyond that point. If we accept the basic premise of modern liberalism – that the state exists for the total and equal liberation of all human beings – then we have to recognise that assisted dying for the terminally ill is really just the first step towards a final outcome in which the ‘right to die’ is absolute. It is inevitable, given liberalism’s imperatives, that sooner or later the distinction between the terminally ill and the merely ill will break down; and it is inevitable after that that the distinction between the merely ill and the healthy-but-depressed will likewise collapse. And from there matters will descend to darker places yet. Good liberals, gesturing always towards equality of opportunity, will come to insist on the equality of opportunity to die. This may take years or decades. But it will happen. And from there, all bets are off – the slippery slope will be shown to be like the side of a great mountain.

In Jack Vance’s most disturbing novel, Wyst: Alastor 1716 – the inspiration, incidentally, for News from Uncibal’s title – we find a bleakly humorous forewarning of what is in store. The first half of the story is set in the city of Uncibal, a place in the grip of a “novel philosophical energy” known as “egalism”, which aims to achieve “human fulfilment, in a condition of leisure and amplitude” through the doctrine of “mutualism”.

Central to this project is “a drastic revision of traditional priorities” so that the conditions of genuine “mutualism” can be assured; the result is the complete emancipation of every individual from familial, sexual, romantic or societal bonds, in order that they be made both equal and free. Nobody may own property and all must share everything with whomever asks. Equal access to sex must be enjoyed, so that ‘copulation’ is to be performed on demand even while nobody is permitted to try to make themselves more sexually appealing than anybody else. Children are brought up separately from parents. Almost nobody bothers to work; anywhere one finds something productive being done it is being performed by an immigrant.

Naturally enough, the results are anything but ‘human fulfilment’. Indeed, one of the favourite pastimes of the populace is the performance and observation of suicide. This takes place at the so-called “Pavilions of Rest”, of which we are told there are currently five, lying within a grand bazaar known as Disjerferact.

“The most economical operation is conducted upon a cylindrical podium 10 feet high,” the main character, Jantiff, writes home to his family:

The customer mounts the podium and there delivers a valedictory declamation, sometimes spontaneous, sometimes rehearsed over a period of months. These declamations are of great interest and there is always an attentive audience, cheering, applauding or uttering groans of sympathy. Sometimes the sentiments are unpopular, and the speech is greeted with cat-calls. Meanwhile a snuff of black fur descends from above. Eventually it drops over the postulant and his explanations are heard no more.

The next is known as Halcyon House:

The person intent upon surcease, after paying his fee, enters a maze of prisms. He wanders here and there in a golden shimmer, while friends watch from the outside. His form becomes indistinct among the reflections and then is seen no more.

Then there is the Perfumed Boat:

The boat floats in a channel. The voyager embarks and reclines upon a couch. A profusion of paper flowers is arranged over his body; he is tendered a goblet of cordial and sent floating away into a tunnel from which issue strains of ethereal music. The boat eventually floats back to the dock clean and empty. What occurs in the tunnel is not made clear.

This is followed by the “convivial” Happy Way-Station:

The wayfarer arrives with all his boon companions. In a luxurious wood-panelled hall they are served whatever delicacies and tipple the wayfarer’s purse can afford. All eat, drink, reminisce; exchange pleasantries, until the lights begin to dim, whereupon the friends take their leave and the room goes dark. Sometimes the wayfarer changes his mind at the last minute and departs with his friends. On other occasions (so I am told) the party becomes outrageously jolly and mistakes may be made. The wayfarer manages to crawl away on his hands and knees, his friends remaining in a drunken daze around the table while the room goes dark.

The last is “a popular place of entertainment, and is conducted like a game of chance”:

Five participants each wager a stipulated sum and are seated in iron chairs numbered one through five. Spectators also pay an admission fee and are allowed to make wagers. An index spins into motion, slows and stops upon a number. The person in the chair so designated wins five times his stake. The other four drop through trap doors and are seen no more.

This is all of course played for sardonic humour, and sure enough it is shortly revealed that the corpses of those who kill themselves in the Pavilions are “macerated and flushed into a drain, along with all other wastes and slops” and then made into a slurry which is “processed, renewed and replenished” at a central plant and turned into food for the city’s inhabitants. But the point is deeply serious: taken to its extreme, if people are to be equal, then why ought the matter of death be an exception? And since the only way to achieve equality in death is to give everybody the right to die when they choose, then why place any restriction on the time of the choosing, or the manner of dying that is chosen?

From those predicates, of course, it is only a very short step to a market in the provision of death, and indeed its transformation into a form of entertainment. And from there it is only a short step to commercial operations relying on the liberalisation of suicide, and promoting its deployment. From there, suicide as spectacle – suicide as pleasure – naturally follows.

Michel Foucault, in many ways the harbinger of the liberal end-state, showed that this is all far from a joke. In an interview he laid the reasoning out very plainly. Since, he argued, suicide is unique to humanity – we are the only animal that does it – we ought to celebrate it, and indeed make it an art:

We should consider ourselves lucky to have at hand (with suicide) an extremely unique experience: it’s the one which above all the rest deserves the greatest attention – but rather so that you can make of it a fathomless pleasure whose patient and relentless preparation will enlighten all of your life. Suicide festivals or orgies are just two of the possible methods. There are others more intricate and learned.

And he extended the thought with a lurid fantasy:

In my opinion a person should have the right not to be rushed, which is very bothersome.

Indeed, a great deal of attention and competence are required. You should have the chance to discuss at length the various qualities of each weapon and its potential. It would be nice if the salesperson were experienced in these things, with a big smile, encouraging but a little bit reserved (not too chatty), and sophisticated enough to understand that he is dealing with a person who’s basically good-hearted, but somewhat clumsy, never having had the idea before of employing a machine that shoots people. It would also be convenient if the salesperson’s enthusiasm didn’t stop him from advising you about the existence of alternative ways, ways that were more chic, more your style.

He even imagined the existence of places like Japanese ‘love hotels’ where couples rent a room for a few hours to have sex, but which were dedicated to suicide: “places without maps or calendars where you can enter into the most absurd decors with anonymous partners to look for an opportunity to die free of all stereotypes”. He continued, “There you’d have an indeterminate amount of time – seconds, weeks, and months perhaps – until the moment presents itself with compelling clearness. You’d recognise it immediately. You couldn’t miss it. It would have the shapeless shape of utterly simple pleasure.”

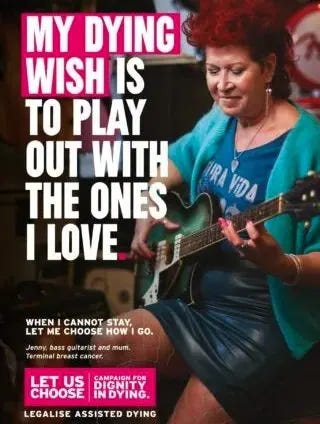

If this all would have sounded far-fetched a month ago, inhabitants of London were in the days leading up to the ‘assisted dying’ vote treated to a series of adverts on the Tube extolling the virtues of “choice”. Each depicted somebody looking forward to their own death and the alleviation of their suffering. These were funded not by a business but a charity (strictly a not-for-profit company) called Dignity in Dying. But they gave us a foretaste of a life to come, wherein public billboards – let’s, in the interests of time, not concern ourselves with targeted ads on social media or TikTok – extol the virtues of dying in particular ways, and at the hands of particular operators for an attractive fee.

The ad at the top of this post has garnered the most interest because it is the one which most nakedly and brazenly gestures towards the future that I have here laid out, but the one which I found most interesting and indicative is this one:

Notice the tagline: “When I cannot stay, let me choose how I go.” Obviously this is supposed to emphasise that ‘assisted dying’ is going to take place in the context of terminal illness. But it also gives the game away, I am sure entirely unconsciously: the point about life is that none of us can stay. We are all in this sense terminal cases. Given this is so, the logic becomes clear – we must all be free to choose how we go. And this is the direction in which matters will inevitably flow. Since it is fair for Jenny, the bass guitarist and mum with terminal cancer, then it will sooner or later become fair for Johnny, the unemployed man who sees no point in going on; fair for Sarah, the lonely old lady living in poverty; fair for Ben, the extrovert attention-seeker with an undiagnosed personality disorder; fair for Geoff, who wants to make a grand political statement; fair for Bethany, who has low self-esteem. Once permitted, there is no principled limit on the scope of assisted dying’s purview, and no principled limit on who will in the end obtain the ‘right’ to it.

This of course foregrounds the importance of the relationship between liberalism and Christianity. Classical liberalism emerged within the context and rubric of a religious society with firmly entrenched moral norms – one of which being that, since life was a sacred gift, suicide was wrong. Over time teaching softened, such that suicide became seen as a desperate consequence of depression or pain, but the central legal prohibition on ‘assisting’ suicide was retained. This was partly because of practical concerns about identifying the circumstances in which ‘assistance’ should be made lawful, but it was mostly because people were squeamish about the idea of the state sanctioning the practice. And that squeamishness derived from a basically religious impulse: the idea that life itself has intrinsic moral value.

Despite declining church attendance and declining importance of religion in public life, this squeamishness has largely endured, even while most people have no real answer for the moral values they take for granted. But we are now (certainly here in the U.K., anyway) far into the process of secularisation and particularly de-Christianisation, such that we can begin to see emerging what our culture will look like in a post-religious age. What we are glimpsing is a society that is thoroughgoingly liberal – liberal to the Nth degree, being unconstrained by the moral norms which classical liberalism took for granted. This will be a society deluded into thinking it is governed by reason and the intellect. But what it will really be is a society in which each and every individual seeks from the state what is in his or her self-interest – a true sibling society characterised by an insistent demand for the combination of freedom and equality which every atomised individual necessarily desires as his or her ideal.

There will be absolutely nothing preventing death itself becoming the subject of this remorseless and unfettered liberal drive, and nothing therefore preventing the right to die from becoming universalised, lionised and ultimately commercialised (though undoubtedly, in the interests of true equality, there will be state-run operations ‘free at the point of use’). The slippery slope will go steeply down and our passage down it will be rapid. Without a basic commitment to the sanctity of life, with the emphasis on sanctity in the strict sense, Foucault’s fantasy – Vance’s parody – is the position to which liberalism will take us. We will live in a world in which the fantasy of equality and freedom in death is a guarantee, and in which the “simple pleasure” of suicide is not merely made available, but marketed and encouraged. This future lies ahead of us; the slope is slippery.

Dr. David McGrogan is an Associate Professor of Law at Northumbria Law School. You can subscribe to his Substack – News From Uncibal – here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

This is pretty much where we are, probably a bit of Hunger Games thrown in too.

You seem to have missed out the finest example of the slippery slope, Logan’s Run.

I’ve never seen it but it keeps being mentioned so I’m thinking it must relate to assisted dying? Are you recommending it?

Not really. It’s about a society living in an underground city in a post-war USA (unknown to the inhabitants). Everybody is supposed to let himself be killed voluntarily upon the 30th birthday. All people wear special, watch-like devices which will light up (and – IIRC – also emit an acoustic signal) when the date for their death arrives. People who don’t obey are called runners and hunted down by a special force dedicated to this task. Logan is a member of this special force and hooks up with woman almost immediately before his own device indicates that it’s time for him to die. He then runs together with the woman and they eventually make it out of the city and continue their flight accross the former USA until they land in a huge library where they encounter the first grey-haired man they ever saw. The movie ends with them re-entering the underground city to liberate its inhabitants and make them live freely on the surface of the earth again.

NB: I hope that’s at least mostly correct. I saw the film twice decades ago and just summarized it from memory. I quite liked it at that time.

The book, This Perfect Day, by Ira Levin is along similar lines, but more chilling!

Not that it matters particularly, but Logan’s device starts to indicate it’s time for him to go because the computer in charge takes some years off him so he can chase the rebels. Understandably, he is a bit miffed by this so he legs it with Jenny Agutter in tow, a pretty sound decision if you ask me. I loved the film as a boy (not least because of JA) but tried to watch it again recently – it had not stood the test of time.

And also Soylent green!

Sorry to be pedantic, but I think this is a diagram of the destination of the slope down which McGrogan warns we are sliding.

There will be absolutely nothing preventing death itself becoming the subject of this remorseless and unfettered liberal drive

Also, and this is part of our deep problem, the “liberal drive” is used to hide the developing total-control state from view. When the development is complete, then the state – i.e. civil servants, police officers, and politicians – will be deciding who dies and when.

Is Trump part of the Liberal drive? Or is this supposedly inevitable slippery slope just a fiction?

We might be becoming more secular, but you forgot to mention the mass importation of immigrants from Muslim countries for our ‘cultural enrichment’…..Not sure what their attitude is to assisted suicide beyond martyrdom is.

BREAKING NEWS

South Korea has declared Martial Law.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/dec/03/south-korean-president-declares-emergency-martial-law

Also protests in Pakistan to free Imran Kahn with people getting shot. As he is anti-Globalist, it’s not being covered much in the MSM.

https://rumble.com/v5tbes8-revolution-in-pakistan-worldwide-protests-demand-jailed-anti-globalist-pm-i.html?e9s=src_v1_ucp

A brief summary: the marxo-fascist death cult is trying to make suicide look cool before mandating it.

If we are to have this law, which I oppose, we must hope the NHS is given the job. The queues could last long enough for us to survive.

Yes the queues would outlast the oldest of old, despite having “saved” the NHS in 2020.

As an atheist, I have always been puzzled by the religious position on suicide. If a person of a religious belief which offers an afterlife where everyone becomes a perfect servant of the omnipotent being, why is it wrong to want to arrive there sooner than later, especially if you have done a good deed in this life to achieve this eternal perfection? Surely suicide is only wrong in an atheistic world where this is your one and only chance to do your best and keep doing it to help society? By dying before your time you have not given back everything you can to society and therefore you are committing a theft of your contributions, so are committing a crime. As it is, I deeply object to the passing of this law, because I never want to be in the position of being offered the cheaper death option than the expensive life saving possibility, as is happening in other countries.

I never want to be in the position of being offered the cheaper death option than the expensive life saving possibility.

Excellent point.

Of course if you are an atheist, then you will have a different mindset, and that’s fine.

But the summary of the Christian ban on suicide is based on your life being a gift from God and an opportunity to grow towards Him. You trust God and leave Him to decide when your mission is complete. By throwing away life you effectively defy Him.

What they will argue is once you have retired, your use is surplus to requirements. I remember when first getting on the property ladder, and the neighbours saying that my dad (farther for the middle classes) should help me because “He’s had his time”…Lovely. But I welcomed the help!

Also in some religions you are rewarded with 14 virgins, or was the figure more?

Thing is, though most ‘religions’ depend on your doing enough good deeds to go to heaven instead of being cut off from God forever, the Christ of Christianity says we can never do enough good deeds – any sin separates us from God. This matters a lot, as he also says – along with most religions – that there is a judgement. So they are crazily encouraging people to jump ship without them having a clue where the lifebelt is? While of course what is happening in this life is horrendous, what happens after we die is a big elephant in the room.

I don’t think that this tendency will endure or that this will stand. Humanity is moving rapidly back towards the sacred in my view, even in the decadent West.

I hope you are right.

You can see the sigjns already. It won’t save us from the shortness of time we have left but far more important will be the turning to our side in the final sequences. The Apocalypse of John says that in the last days men shall seek death and shall not find it. Death shall flee from them. This is very significant. Endurance of agonies previously unknown and the suffering can’t be stopped and shouldn’t be stopped.

When you rely on a work of fiction to support your argument, you’ve already lost.

Euthanasia of terminally ill, many suffering terribly, happens every single day. Why hide this? Does hiding this make us feel safer? We allow our pets access to this to terminate their end of life suffering. The big issue, I think, is that governments and their bureaucracies have become untrustworthy and that this whole issue will become mismanaged and abused. Governments and Public Health regressive actions over the last 4 years indicates we are not ready for this.

Soon , in the binterest of saving money, you will be offered the option of ‘assisted dying’ by the state or continuing on but without state-funded health care.

If suffering is a criteria foe ‘assisted dying’ then all those who suffer physical, emotional or mental suffering are at risk.

I thought for one moment I was going crazy. I have absolutely no idea what is being said in this article. Translation anyone?