Marx said that the problem was expropriation. His suggestion was that we should “expropriate the expropriators”. Sometimes we hear it said that our problem is inversion. Our current system seems to involve a continual inversion of all reality. Our ideals, values, political correctness, official ideology, are all based on lies. And so the suggestion, by analogy, should be that we should “invert the inverters”. You know: Resist Net Zero. Condemn Stonewall. Glue Protestors to their Jail Cells. Tear up the Guardian. Troll Human Resources. But there is a problem.

The problem is that in order to invert the inverters we, too, have to engage in inversion. We might want to be good, true, white, angelic, eternal, pure, but we have to come down to earth and get our hands dirty, sell our souls to the devil, engage in usury, take the jab. We are forced to use language, the same words our enemies use: equivocal words. We even sometimes have to use the same statistics, even though we know they are damned. If we want to clear out the Augean stables, then we have might have to be as merderous and malodorous as the shit we shovel.

Inversion is, famously, the game of the devil. We find it everywhere. It is in hypocrisy. It is in rhetoric. It is in unreliable narration. Inversion, if we were to analyse it, comes in many forms: substitution of one thing for another, representation of one thing by something else, the transvaluation of values (to use Nietzsche’s pretentious phrase), or, in English, making what is good seem bad and what is bad seem good. As soon as we suspect that inversion is a problem then we have the whole world of conspiracy open up to us. This might seem an argument against inversion. We don’t want to be conspiracy theorists: for, why, then we might end up like RFK Jr. or James Delingpole! But then we notice that it might be necessary. For the entire mainstream political order seems to be committed to deny the existence of inversion while continually engaging in obviously inverted activities.

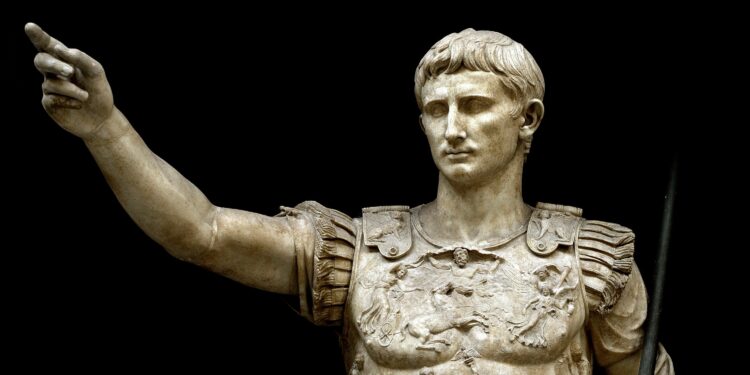

When did inversion begin? I’d say it is as old as language. It is only when one has language that one can say “This is good” of something that is bad. It is only in language that meanings take the form of oaths, where one may be confused or cursed by someone else’s bad use of language or may be cursed or confused by one’s own bad use of language. But even though inversion is as old as language, and, primitively, of course much older (since animals dissimulate, imitate each other, parasitise), I’d say that historically we might as well associate its insertion into politics with the Emperor Augustus. I have his image framed in my office, and this is why.

In all my reading in the history of politics, I have found nothing as clear or as remarkable as Augustus’s achievement in appearing to restore the republic while actually establishing the principate. Everyone knew what was going on, but they accepted it, as the cost of security. It was a lie, the greatest lie ever told by a statesman. It destroyed the old political philosophy of Plato. It destroyed any attempt to put politics on a foundation of truth. (We turned to religion for truth. Later science.) And it became the paradigmatic lie, since it was copied by everyone who admired Rome, or who was influenced by it, which, since this includes the European states, and since the European states colonised the entire world and ideologised the bits they didn’t colonise, means the entire world. Now, everyone in the world lives in a political society which both is and is not the thing is claims to be: republic, democracy, what you will. I keep seeing halfwits like George Monbiot (name out of a hat, almost any other name could be substituted) making lists of things that are bad (to which they add Orban and Trump when the list looks unconvincing), wholly failing to recognise that they are engaged in a desperate attempt to take sides in a pot and kettle competition. Imagine a game of ping pong in which one side continually claims moral authority and yet keeps having to flick and slice and spin and smash the ball around a small table like his opponent. (“But I have already won!” protests Monbiot, as the ball flies past his ear again.) That’s most modern political dispute, especially on the self-satisfied and complacent side, which we may call “left”, if we want, or “mainstream”, or “deep state”.

Inversion is a great problem.

The master-text of inversion, though ironical, is Bernard Shaw’s ‘Don Juan in Hell’, in which heaven is ugly and boring, while hell is amusing. Shaw has his characters discuss life and death. The analysis of heaven and hell is made in terms of earth. Earth is where we are slaves to reality. Reality on earth is diremptive: dominated by death but full of men and women seeking life, and seeking to realise life in different ways. Everything is obscured by hypocrisy since everything is divided. It is only if we understand this that we understand what hell is. For hell is a pure place, an abstraction out of earth. It is the place where lies are true. (The Devil is the prince of lies.) It is where the things that we believe on earth – about justice, good, happiness – are allowed to be true.

Here [in Hell, says Don Juan] you call your appearance beauty, your emotions love, your sentiments heroism, your aspirations virtue, just as you did on earth; but here there are no hard facts to contradict you, no ironic contrast of your needs with your pretensions, no human comedy, nothing but a perpetual romance, a universal melodrama.

But, for Don Juan, a world in which lies are true is not a world he wants to live in: so he leaves for Heaven, which is where we are no longer enslaved by reality or by lies but free to become what Shaw calls “a master of reality”. Well!

Shaw’s account of this is equivocal, not only because he puts different arguments in the mouths of his characters (Don Juan, Dona Ana, the Statue, the Devil), but also because each character is broadly conceived and possesses a fragment of Shaw’s ironical self-consciousness which makes every position unstable. He was not writing a treatise.

But notice how Hell is inverted. Shaw inverts the Catholic conception of Hell, as a world of eternal torment for the damned. It is now a sort of Benthamite world where the felicific calculus is always turned up, in Spinal Tap manner, to 11. It is where the greatest happiness of the greatest number is “Roll Up! (Satisfaction Guaranteed)”. But it}s also a world in which we live with our illusions: since it is where our illusions are true. Maurice Cowling always said that Shaw was all about “illusionlessness”, a good word. But illusionlessness is a state which, though imaginatively attainable in the abstract, is actually unattainable. He who would be illusionless would be a god. So, and this is Cowling, not Shaw, we who live in the concrete world cannot be without illusion, and it is through illusion that we find truth, even if this is an arbitrary truth: for it is ours, what we have been given, and not something not-ours that we only imagine by stripping all the colours and sounds of our given world away to leave not a wrack behind.

Shaw thinks that most of us want hell. We want love without its suffering. We want purity. But this is hell because it is unreal: it is the lie, the surface, without the reality. Shaw took the reality to be at two levels: one biological: the need for life to propagate itself, which he took to be the woman’s part; and the other the highest consequence of the man’s part, which is philosophical: the attempt to imagine a higher form of life. This is, probably, completely mad: but Shaw had his own prosaic poetic habits too, and, as someone who kept trying to go, in his own words, “as far as thought could reach”, kept arriving at what H.G. Wells called “mind at the end of its tether”. Shaw and Wells: those early transhumanists; Wells, a believer in a World State. Both trying to turn Evolution, in different ways, Lamarckian or Darwinian, into a Purified Higher World.

The word Shaw used was “superman”. This was before the word was made childish by DC Comics. It was Nietzsche’s word, Übermensch. ‘Don Juan in Hell’ was part of the middle act of Shaw’s play Man and Superman. Shaw did much to popularise the word “superman” and may have invented it. He considered the alternatives “Over-man”, and “Beyond-man” and maybe even a variant I saw somewhere, “After-man”, but chose “Superman”. But nowadays we talk not of supermen but of transhumans. This is odd. Super means above, higher, better. But trans means across, different, like transsexuals: different, but not better (maybe worse). It is amusing to think that Shaw, science fiction and fantasy are responsible for why we cannot speak of superhumans and must instead settle for mere transhumans, with the suggestion that they won’t be better than us.

This is all inversion on top of inversion. But the reason I mentioned Shaw in the first place is because he puts in Don Juan’s mouth a litany of what we would nowadays call rhetorical redescriptions.

In this Palace of Lies a truth or two will not hurt you. Your friends are… not beautiful: they are only decorated. They are not clean: they are only shaved and starched. They are not dignified: they are only fashionably dressed. They are not educated: they are only college passmen. They are not religious: they are only pew-renters. They are not moral: they are only conventional. They are not virtuous: they are only cowardly. They are not even vicious: they are only “frail”. They are not artistic: they are only lascivious. They are not prosperous: they are only rich. They are not loyal, they are only servile; not dutiful, only sheepish; not public spirited, only patriotic; not courageous, only quarrelsome; not determined, only obstinate; not masterful, only domineering; not self-controlled, only obtuse; not self-respecting, only vain; not kind, only sentimental; not social, only gregarious; not considerate, only polite; not intelligent, only opinionated; not progressive, only factious; not imaginative, only superstitious; not just, only vindictive; not generous, only propitiatory; not disciplined, only cowed; and not truthful at all: liars every one of them, to the very backbone of their souls.

Don Juan says that all our ideals are just “nothing but words which I or anyone else can turn inside out like a glove”.

So when we hear politicians telling us something that is obviously inverted, we of course want to turn out the glove. We want to invert the inverters. But this is ultimately at best only a local activity. The inverters cannot be entirely inverted: otherwise we would invert all reality, and end on Shaw’s stage where there is, to use his stage directions, “No sky, no peaks, no light, no sound, no time nor space, utter void.”

We have to choose our battles. We are fortunate in that the battles are unusually clear in our time.

Dr. James Alexander is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at Bilkent University in Turkey.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.