Many valued readers advised against wading more deeply into Unlearn CO2, that doubtful and ridiculous tome of climate lunacy that first came to my notice a week-and-a-half ago. Why should we waste our attention on the ravings of crazy people, they asked? Surely, our time is better spent pondering what the well-informed, the measured and the mature have to say.

I understand the objection, but I must reluctantly disagree. Climatism is a political programme bound to a broad social movement. Most of its momentum comes not from The Science or The Experts, but from diffuse cultural forces that we should probably try to understand, if only because they are driving our entire civilisation straight into the ground. Against all advice, I will therefore steer the plague chronicle into this ridiculous quagmire of leftoid green babble, with a look at our first lesson in Unlearnings, namely ‘Unlearn Repression’.

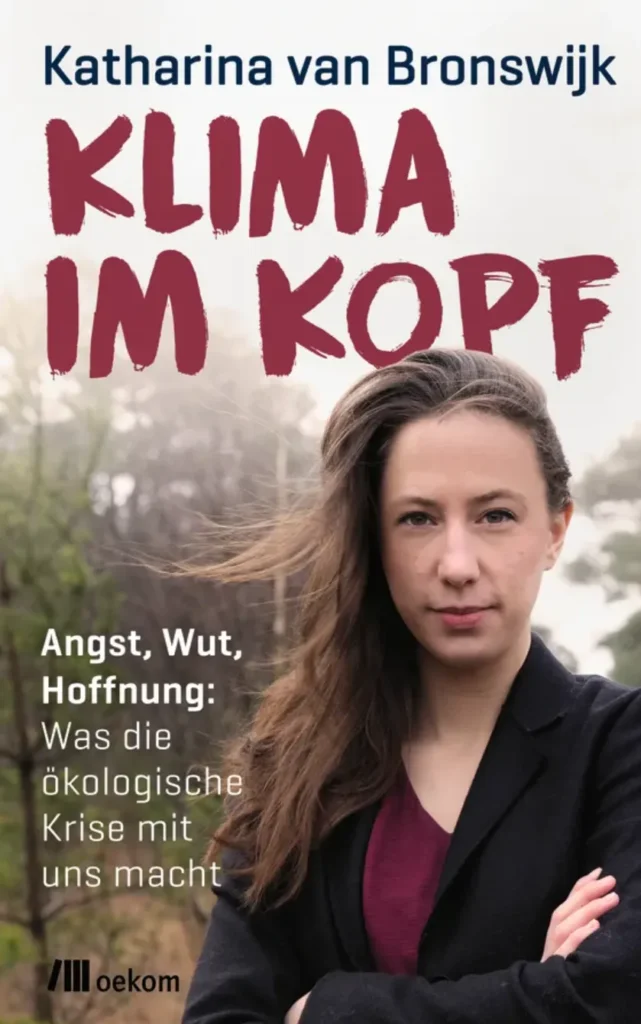

This superficial and disorganised essay is the work of an infuriating young woman named Katharina van Bronswijk. She’s a psychotherapist best known for her 2022 book, Climate in Our Heads. Fear, Anger, Hope: What the Ecological Crisis is Doing to Us. It belongs to that genre of inevitably unreadable monographs in which the author herself appears on the cover, looking windswept, pioneering and undaunted:

“Climate feelings” are van Bronswijk’s niche in the extremely crowded enterprise of CO2-bothering. In ‘Unlearn Repression’ she argues that we should not suppress our negative feelings about climate change, but rather embrace them in constructive ways on behalf of the planet.

Now, van Bronswijk is the kind of deeply unoriginal person who just says the same things over and over. Everything she writes in ‘Unlearn Repression’ flows directly from Climate in our Heads; she’s been digesting, reheating and reworking this same overboiled intellectual artichoke for almost two years now, through various media interviews and even in this English-language TEDx Talk. Throughout this woman’s work is the vague anxiety that the climatists have perhaps overdone it with doom and gloom, and that a lot of people have had enough of hearing about a climate apocalypse that never quite happens.

Van Bronswijk is naturally very dumb, but more than that she is painfully condescending, oblivious, verbose and just awash in litres of estrogen. I defy anyone to read her work and not come away from it a raging misogynist. This odious overpromoted schoolmarm belongs out of sight in a childcare centre teaching young children the alphabet. Perhaps she should also be in a choir, or part of a local environmental club dedicated to collecting litter in parks. That our society has denied van Bronswijk and so many others like her these proper outlets for their instincts and instead pushed them into public activism and intellectual production itself explains a great deal of what is wrong with the world.

‘Unlearn Repression’ opens with some autobiographical details, because of course everything van Bronswijk talks about is all about van Bronswijk. Like so many Germans of her generation, she was radicalised by school climate propaganda – specifically, by her teacher’s fateful screening of that classic propaganda film, An Inconvenient Truth:

Back then… I was happy for the welcome distraction of watching a film instead of doing normal lessons. But afterwards I was shocked and asked my mum for answers to all the questions and challenges. She didn’t have any solutions for me, how could she? I was alarmed and started to think about the impending consequences of climate change and what could be done about it. I found approaches in newsletters from NGOs and by reading up on animal and environmental protection… That was when my dream bubble burst and I realised: the world is unfair and, unlike all the Disney stories of my childhood, there will be no single heroine who saves the world. And there is no magical or technical miracle solution either.

Al Gore’s film so terrified the young van Bronswijk, that for a while she retreated into conspiratorial theories about why climate change is not happening, which qualifies our crayon psychotherapist to pronounce upon the psychology of those who deny the climate. This deeply evil and irrational movement is driven primarily by “white men” because they “still enjoy most of the privileges in our society, and therefore have the most to lose”.

The necessary change in our way of life and the upheavals of recent decades are threatening these privileges. We’re questioning the role of “men”, we’re questioning social narratives of superiority through gender, through academic attainment, through professional success, through the burning of fossil fuels… through the over-consumption of luxury goods. This is understandably unsettling and can trigger feelings ranging from anger to a sense of threat… for those who will have to give up their privileges in the future.

We are only on the third page of this abomination and already van Bronswijk is laying bare her ulterior motives. At first, she thought climate change was terrifying and she sought after reasons to doubt it was happening, but then she realised it was just great for sticking it to old white men, and so once again she was fully on board. Before even mentioning one single, concrete negative consequence of carbon emissions, van Bronswijk is deploring male “privilege,” and those advantages of the wealthy and the well-educated that climatism must sooner or later spell the end of. All of these villains will have to give up their “fancy cars”, they will have to go without their precious “status symbols” and those things they “consider especially masculine”. It is the standard, shopworn ressentiment of leftism in general, presenting merely a different matrix of justification.

This is a political programme that naturally inspires anger in people, and in this way we come to our first Climate Emotion. Sometimes, van Bronswijk writes, “our biographical background means that we tend to repress certain emotions and overcompensate with others”. Those “angry citizens” (“Wutbürger”) who vote for AfD are in fact dealing with feelings of “fear” or “insecurity”, which they repress by expressing “Anger at the Greens, at people who eat a vegan diet, who live in big cities, who are young, who have a refugee background, and so on and so forth”.

While this airtight pop-psychological analysis shows that the anger of the climate denialists is illegitimate, there is another kind of anger that we must embrace, if reluctantly. This is Climate Anger:

Climate anger makes us aware of the injustices of the world out there and our own limitations. For many, fairness and justice are extremely important values – and when there is a lack of inter-generational, social or global justice, this makes many people angry. A large part of the local population sees climate change as a threat and also the need for a transformation of our lives, and many want this transformation to be fair.

The problem, as van Bronswijk sees it, is that nobody can agree on what amounts to “fairness”, which opens “a great potential for conflict…. if people can’t regulate their anger and channel it constructively”. A lot of leftists really, really love anger; Antifa are some of the most murderously enraged people I’ve ever encountered. Alas, van Bronswijk’s schoolmarmery warns her against this more entertaining approach. She would prefer to “regulate our anger” and use it as a motivation to “sign up for projects in social justice, go to protests and support petitions”. That’s right, you might be angry that the earth is melting before your eyes, but the best thing to do about that is to self-soothe by… attending Friday lunch hour demonstrations, volunteering and signing things. It’s at least some comfort that if the climatists are ever out of power, their crack schoolmarm brigades will fight rearguard actions in favour of destroying the economy and our lives in the most tepid and ineffectual ways imaginable.

What are the other Climate Emotions, you ask?

Well, there are the boring ones, like Climate Guilt and Climate Shame, which help us to “take responsibility” but should be properly managed lest the climatists become “too missionary” in their bearing and start berating everybody about their climate guilt. Here again, we encounter a quiet, half-acknowledged fear that the climatists have perhaps overreached, but of course it is nothing that van Bronswijk’s psychological expertise cannot solve.

More ridiculous is Climate Fear, which “warns us that extreme weather events are potentially life-threatening, that we can lose our possessions and that our children’s future looks ever bleaker”. Here it is important “not to be afraid of fear”, because being freaked out about imaginary horror scenarios is a great motivation, and it will “hopefully give us enough bumblebees up our arses to get off the sofa, spit on our hands, look for allies and get going together”.

Next up are Climate Disgust and Climate Contempt. These are “helpful feelings” that “protect us from coming into contact with things or associating with people who could harm us (or our reputation)”.

So the next time you turn up your nose in disdain at your neighbour’s Caribbean cruise or weekend trip to Mallorca or [insert climate sin of your choice], it’s disgust at work here, telling us clearly that (in our opinion) this is simply no longer the thing to do.

Just imagine living next to van Bronswijk. In any era and under any kind of political regime, she’d always be a wretched harpy peering through her blinds at passersby and cataloguing the misdeeds of her fellow man. Climatism, however, provides this woman with an entire moral system to justify her petty exercises in self-superiority. She gets to look down her nose at her cultural inferiors and save the climate at the same time.

After all of this, we finally get to our next Climate Emotion, which is Climate Mourning – specifically, “solastalgia”. This is a retarded and linguistically incoherent neologism coined by the “environmental philosopher” Glenn Albrecht, which describes feelings of “existential distress” provoked by environmental change. Van Bronswijk reports that she feels particularly intense solastalgia when contemplating all the dead spruce trees in the Harz forest, which she believes have been “killed by heat”. The way van Bronswijk deals with Climate Mourning is the same way one suspects that she deals with most everything else: she talks and talks and talks and talks and talks about it.

During the mourning process, it helps to talk to other people about your feelings and to be understood… I need to find someone around me who is willing to address these feelings. Someone who can tolerate them and has the emotional capacity to create a space for these feelings with me. When we empathise, when the other person listens, agrees and mourns with us, it helps us to digest the situation emotionally. It’s like heartbreak – you just have to get through it.

Since we’ve extended our sympathy to van Bronswijk’s neighbours, we’d be remiss if we didn’t also spare a thought for her long-suffering friends. Arguably, their lot is orders of magnitude worse. Imagine having to put up with ridiculous hours-long conversations in which this silly logorrhoeic woman details her profound sadness over dead plants. There are few people alive who could stand it, which would be why our heroine finally admits that: “Finding someone like that to talk to can… be difficult.”

‘Unlearn Repression’ closes with an appeal to “Unlearn Crisis Exhaustion”. From Covid to Ukraine to Gaza, there have just been too many crises and a lot of people don’t want to hear about climate change anymore. They must therefore unlearn their crisis exhaustion so they can worry about van Bronswijk’s pet issues once again. One way to overcome crisis exhaustion, is to join activist group and go to protests, sign petitions, and do all manner of other activist-y things, which (as van Bronswijk tacitly recognises) are of course really about fulfilling social and emotional needs and not actually about changing anything. We also need to cultivate “joy for the future” by talking about “how great our life will be when we’ve unlearned CO2”.

There are still spaces in our society where we can be creative together and dream of a beautiful, colourful future within the limits of our planet. These can be existing initiatives or model projects in which we can already partially experience the new reality and the beautiful future right now. Or maybe it’s a group of enthusiastic colleagues with whom we spend our lunch break thinking about how we can shape the transformation for the benefit of the company. No longer burning fossil fuels is not only important for the climate, it also leads to many co-benefits that we rarely talk about: clean air, clean water, healthy soil, delicious food and better health.

There are also of course the co-drawbacks of “no longer burning fossil fuels” – for example, the inevitable deaths of billions of people. We can only hope that the “delicious food” of our carbon-free future utopia will be delectable enough to compensate. It will certainly be very scarce.

I don’t know how to conclude this, except to say that I absolutely loathe this woman. Presently, we are sparing no effort to destroy our economies, our societies and our everyday lives, and that is bad enough. What is almost too much to bear, is the additional humiliating fact that the most vocal advocates for the engineered destruction of our civilisation turn out to be such empty-headed nitwits. The cartoonish banality of this idiot woman’s thought is an absolute disgrace. It is like being lectured on the necessity of an impending mass slaughter in saccharine tones by a pink Sesame Street muppet.

This article originally appeared on Eugyppius’s Substack newsletter. You can subscribe here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.