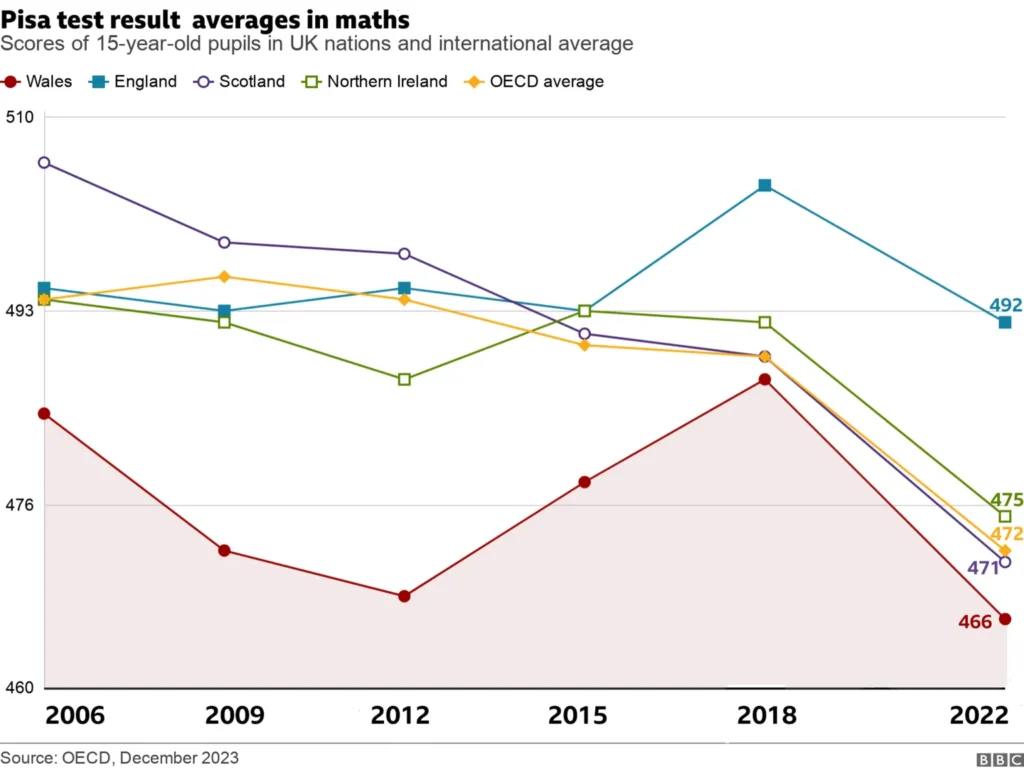

I‘m currently on a speaking tour down under, banging the drum for free speech, so am watching my country go to rack and ruin from 10,000 miles away. I remember a palpable sense of a cloud being lifted when Gordon Brown left Downing Street in 2010, not least because, following the inconclusive election result, it looked as though Labour might cut a deal with the Lib Dems and cling on to power. I was particularly relieved when Michael Gove was appointed Education Secretary because it meant the free schools policy was part of the coalition agreement that David Cameron had thrashed out with Nick Clegg and I’d spent a year struggling to set up a school with a group of other parents on the assumption it would become easier after the election. Over the next four years, I co-founded four free schools and became the country’s leading advocate for the policy. I didn’t realise at the time that education reform would be one of the few – the very few – successful policies the Conservatives could point to after 14 years in Downing Street. Needless to say, Labour has pledged to take a sledgehammer to Gove’s reforms in spite of the evidence, both domestic and international, that they’ve boosted educational attainment. Expect England’s schools to become more like those of Wales, where Labour has been in charge since 2009. In the latest PISA assessments, Wales was shown to be the worst performing nation in the U.K., significantly below the OECD average.

That cloud has returned, obviously, although my fears about not seeing sunlight again until 2034 have receded. Yes, Labour has won a landslide, but it’s not quite Starmageddon. According to the exit poll, his landslide, predicted to be the largest since 1832 in one eve-of-election poll, is in fact smaller than Tony Blair’s in 1997, although not by much (170 v 179). More encouraging, if the exit poll is to be believed, is that Labour only managed a vote share of 36%, significantly lower than in 2017 under Jeremy Corbyn (40%). By contrast, the Tories and Reform won a combined share of 43%. Sir Keir has won a landslide but not a mandate – his own majority is down by 16,000 – although I doubt he’ll be constrained by that.

The Left of the Labour Party will point to the fact that Starmer polled fewer votes than Corbyn – we don’t know that for sure yet, but it looks likely – and dispute that Labour only won this election by tacking to the centre, just as the Right of the Conservative Party will argue the Party didn’t lose by abandoning the centre ground (which is the prevailing orthodoxy among ‘One Nation’ Tories, believe it or not). And they’d both be right, in my view. In spite of Starmer’s victory, technocratic managerialism – or “stakeholder capitalism”, as Klaus Schwab calls it – hasn’t exactly triumphed in this election. The Uniparty – that is, the Conservative Party under Sunak and the Labour Party under Starmer – got a bloody nose in the sense that the two main parties received an even lower share of the vote – 62% – than they did in 2010 (66%). That’s a lower share than in 1983 at the height of the SDP‘s popularity (70%) and worse than in either of the 1974 elections. Indeed, lower than in 1923, when the two main parties won 68.7%. You have to go all the way back to 1918, when the Liberal Party hadn’t yet collapsed, to find Labour and the Conservatives collectively polling a lower vote share (59.2%).

The superficial take on the result is that the U.K. is bucking the anti-technocratic trend sweeping the rest of the globe, particularly France where we may be witnessing the death throes of the Fifth Republic. But look beyond Labour’s landslide and the real story of the last six weeks is the rise of Reform and the lack of enthusiasm for the two centrist parties. Indeed, if we had PR in the U.K., as they do in the EU, we might now be looking at a Right-of-centre coalition with a populist leader at the helm and a move away from the Uniparty’s position on immigration and Net Zero, as well as its uncritical embrace of sectarian identity politics. We may have to wait another five years before that happens, but it seems unlikely, to put it mildly, that Starmer’s premiership will breathe new life into this calcified ideology. Much more likely is that a succession of policy failures, leading to a financial crisis, civil unrest and rolling black-outs, will be the death knell of technocratic managerialism. In 2029, the British electoral may finally vote for real change.

John Gray was very good on the imminent collapse of technocracy in a piece for the New Statesman on June 19th:

The recent YouGov survey showing the long-dreaded “crossover”, with Reform 1% ahead of the Tories, was the moment technocracy hit the rocks. Rule by technocrats means bypassing politics by outsourcing key decisions to professional bodies that claim expert knowledge. Their superior sapience is often ideology clothed in pseudo-science they picked up at university a generation ago, and their recommendations a radical political programme disguised as pragmatic policymaking. Technocracy represents itself as delivering what everyone wants, but at bottom it is the imposition of values much of the population does not share. A backlash was inevitable.

Populism is, among other things, the re-politicisation of issues the progressive consensus deems too important to be left to democratic choice. Immigration was one such issue, climate policy another. Both have stormed back into the political realm.

Gray’s conclusion struck me as particularly prescient:

In functioning democracies, technocracy rarely works for long. Relying on scraps of academic detritus, its practitioners struggle to keep up with events. Even when their theories are sound, they do not legitimate their policies. Anthropogenic climate change is a scientific fact, but science cannot tell you what to do about it. Conflicting values are at stake, some of them involving major losses. What entitles a caste of bureaucrats to make these tragic choices for the rest of us?

While the populist revolt is gathering momentum, Labour is going all in for technocratic management. Rachel Reeves proposes to give the Office for Budget Responsibility a greater role in approving fiscal policies. The recent record of the Bank of England does not inspire confidence in such bodies. In times as uncertain and clouded as ours, devolving the powers of government to rule-bound institutions is a fast route to ruin.

The challenge of the next five years, assuming this is a one-term government, will be to stop Starmer and his army of blobby bureaucrats vandalising the English Constitution – or, rather, continuing the process of transferring power away from Parliament and into the hands of judges, officials, quangocrats, regulators and international bodies that was begun by Tony Blair and which the Tories did nothing to reverse over the past 14 years. In the Daily Sceptic, J. Sorel has warned repeatedly about this constitutional vandalism (see his articles here) and elsewhere David Starkey has been raising the alarm. This will be a last ditch effort of the professional managerial class to resist the coming populist revolt – to neuter parliament so effectively that when the insurgents arrive in Downing Street in 2029 and start pulling the levers to stop mass immigration and abandon the ruinous carbon emission targets nothing will happen. Number 10 will belong to the ‘dignified’ part of the constitution, along with the House of Commons and the House of Lords, assuming it hasn’t been replaced by a Senate of the Nations and Regions, God help us. Although, as Matt Ridley pointed out recently in the Spectator, the Blob is already in charge in key policy areas.

Preserving the English Constitution won‘t be the only challenge. Trying to keep the Conservative Parliamentary Party united over the past 14 years has been like herding cats – one reason we’ve had five Prime Ministers in that period. What hope, then, of uniting two Right-of-centre parties? Already, a schism has opened up between the different factions on the Right of the Conservative Party about whether to admit Farage, with Suella Braverman arguing for and Kemi Badenoch against. I’m fairly confident the next leader of the Tory Party will be a Right-winger, not least because the Left’s strongest candidate, Penny Mordaunt, lost her seat in the early hours of this morning. But if it’s Kemi, she’s going to have to patch things up with Farage or risk facing a repeat of what happened on Thursday at the next election.

The other story of the night, of course, is the emergence of the Muslim Vote, with pro-Palestinian candidates having taken several Labour scalps at the time of writing. If the Right can unite and the Muslim Vote turns into a fully-fledged political force, that could lead to a reversal of Starmer’s fortunes in 2029. Just when you were breathing a sigh of relief about the demise of the SNP, another ethno-nationalist party has sprung up – only in this case, the nation state its supporters owe their allegiance to is Gaza rather than Scotland. That’s bad news for the country, but could be good for the Right. If Starmer criminalises Islamophobia, allows Sharia courts to flourish and changes the law to permit Muslim prayer in schools in an attempt to stop Labour haemorrhaging support to the Muslim Party, that would open up a clear dividing line between the Nat Cons and the radical progressive-Islamist alliance. Queers for Palestine versus Pensioners For Britain. I think the Faragists wold win that contest.

So not a good night for conservatives like me, but I’m not convinced it heralds a two-term Labour Government. On the contrary, we may be glimpsing the outline of a Right-wing coalition that could sweep to power in 2029.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Now let’s contrast this comical farce to the crimes that evil gnome Fauci actually did commit, as per the previous article on here. Because if there were any justice, *that* should’ve been your ”trial of the century”. But as I’m sure we all know, hell will freeze over before he sees the inside of a prison cell. A bit more dirt on Mr Untouchable. No wonder he always comes off as so chuffing arrogant;

”During the pandemic, the American people started to feel that Big Government was very cozy with Big Pharma.

Now we know just how close they were.

New data from the National Institutes of Health reveals the agency and its scientists collected $710 million in royalties during the pandemic, from late 2021 through 2023. These are payments made by private companies, like pharmaceuticals, to license medical innovations from government scientists.

Almost all that cash — $690 million — went to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), the subagency led by Dr. Anthony Fauci, and 260 of its scientists.”

https://nypost.com/2024/06/02/opinion/nih-scientists-made-710m-in-royalties-from-drug-makers-a-fact-they-tried-to-hide/

It was a sham trial from the very beginning but it will backfire on corrupt Biden. If America wants to see a genuine lifelong criminal they only need to look at the White House and take a glance at Ukraine and his sons laptop.

I hope Trump takes the pair of them to Court and slams the door behind them. Then again, Trump isn’t Biden so will just get on with the job he will, once again, be elected to do.

I’m not a mad fan of Trump but Biden is a corrupt man and long has been, his son is arguably worse. I recall the laughably named Democrats calling Trump a Warmonger. Trump never fired one shot. Biden started firing 30 days into his corrupt “Presidency”. He never did explain why, in some places, there were more votes than constituents.

That’s the left for you. Always accusing other people of being what they themselves are.

I hold no remit for Trump but honestly it will be worth seeing him re-elected just for the reaction. Since his conviction, his campaign (which I’m sure he has plenty of money to fund himself) has apparently been receiving millions in donations from the ‘little people’ incensed at what they have seen happen.

I hope it back fires but the NPC mob will believe anything Biden says.

I hope he fires back at those jibes from De Nero. He seems to be living up to his character in ‘Meet The Fockers’, a stooge for the military industrial complex.

So far, my experience has been that those who are happy that Trump has been convicted or don’t mind because they don’t really like him will not be able to explain what he has been convicted of. They can’t explain any of it. They are basically NPCs that have heard the sound bites about Trump being charged and convicted and act accordingly in strict NPC fashion.

Those who understand what has happened are horrified and very very worried.

That said, it’s not the worst thing that has happened in US presidential history. John Kennedy was murdered in what amounted to a coup. And his brother Robert also when he was about to become president. The US is still a bit rough around the edges when it comes to regime change. Not like the UK where they can depose not one but two Prime Ministers in a matter of weeks and it all looks like it’s been done by the rules.

Agree entirely but Biden is mad, deranged and senile. The fact he’s about to die makes him more dangerous than the average Potus.

Worse, I think he is surrounded by people pulling his strings who are actually wicked.

Guilty of spoiling the Liberal Progressive, One World Government, Climate Change Party, where the commies get to divvy up the planet while pretending they are saving it. They cannot have Trump coming along and withdrawing from any more climate treaties. In the sixties he would have been shot in his Lincoln Continental, but these days they gotta be a bit more subtle about it.

As the Babylon Bee put it: Donald Trump found guilty of being Donald Trump.

https://www.globalresearch.ca/trump-verdict-us-civil-war/5858746

A good article from Global Research confirming Paul Homewood’s interpretation. An interview with the gorgeous Megyn Kelly also embedded.

This appalling abuse of the justice system really does put the USA on a par with Bannana Republics. How could they be so crude as to find The Donald guilty on unproven charges? Hopefully this doesn’t set the precedent for other Western nations although in our case we certainly are pushing the boundaries.

As Mark Steyn puts it. it is worse than a banana republic. This is not some backwater, this is supposed to be the helm of the free World.

I heard that the prostitute Stormy was calling for him to be jailed immediately. They must be getting desperate. Was he that bad a fu@k, I mean, she already got paid I assume the first time, and then after for hush money. That is one expensive prostitute. Go to Thailand and you will get a much better deal.

“Trump never fired one shot. Biden started firing 30 days into his corrupt “Presidency”…

And the American MSM, which along with BBCs Trusted News Initiative, must be busted up as illegal info monopoly and racket, began calling for his Impeachment literally on his 2017 Inauguration Day.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2017/01/20/the-campaign-to-impeach-president-trump-has

Some simple facts to remember — It is a Democrat State — and a Democrat judge who is on record wanting to take him down with a daughter that sells merchandice in the downfall of Trump. Only in America as they say!

“ But astonishingly, here in Britain the media almost to a man has ignored them all and instead lazily assumed that Trump must have committed a crime.”

I don’t find that at all astonishing. Almost everyone I know dislikes Trump, thinks he is dangerous or a fascist or something- I doubt any of them could name a single policy decision of his though. Even people I know who probably vote Tory here view him with disdain, probably not smarmy enough and too brash, not at all “respectable”.

Make no mistake. God sent President Trump