The estimable David McGrogan has done much for bringing an understanding of law to the pages of the Daily Sceptic. In an era in which everyone talks about science, it is very important that there will be some of us who keep talking about law — and literature — and politics.

McGrogan’s latest essay argued — it was a complicated piece and worth summarising — that Lord Diplock, a renowned old horse-rider of a lawyer, told the House of Lords in 1985 that he could see no reason why the lawyers shouldn’t be able to subject prerogative powers to judicial review. (McGrogan is very funny on the trickiness of the bland phrase, “I see no reason”.) This was part of the thing Jonathan Sumption has written about in his recent non-historical books: the tendency of lawyers to turn political convention into legal regulation: that is, more simply, the tendency of law lords to go after power. But the broader point is about the civil service. McGrogan argues that Government should be able to do what it wants with the civil service, free of any constraint: where constraint might come from judicial review, or from trade unionisation. Anyhow, one way or another, it is necessary to have a bonfire of the bureaucrats.

This is a useful suggestion. Some of us have tended to exaggerate the political causes, or, at a deeper level, the cultural and theoretical causes, of what has gone on since 2020, ignoring bureaucratic and legal causes. And it is quite possible that at some dim and clotted level the reality is that the Circumlocution Office (as depicted in Dickens’s Little Dorrit) has been in control all along, and that it is not, as it was in the 19th century, a hindrance to justice, progress and care, but is, in the 21st century, a hindrance to common sense and good order. For those of you who have not read Little Dorrit, the point of the Circumlocution Office — see chapter X, ‘Containing the whole science of Government’ — is how not to do it: how not to do Brexit, how not to do Covid, how not to do Immigration, how not to do Education, how not to do Civilisation.

In order to add to McGrogan’s vision of what is wrong, let me say something about two things, coup d’état and the universal class.

Firstly, the universal class. In his Philosophy of Right Hegel used this phrase, in German of course — der allgemeine Stand — to refer to the civil service. In every society, he suggested, we have classes or estates and we have individuals, all of whom are pursuing their own interests. But there is one class that is not serving its own interest, because it is serving the public interest. This is the universal class. For Hegel, this meant bureaucrats.

There are two things to say about this. The first is that Marx, in the course of inverting Hegel, decided that the universal class was not the bureaucracy but the proletariat. Clever. And, indeed, this is still a favoured alternative. (Consider Graeber, Occupy, Momentum, UKIP etc.) Even McGrogan has to fall back on it, saying that if we think that the Government has been unfair to the civil servants then we can always appeal to the electorate for justice. Perhaps the only other serious candidate for a universal class is the academic-fantastical one of the intellectuals and experts: the people who know how to do it. You know, the COVID-19, Net Zero, Diversity brigade.

The second thing to say is that any member of the universal class, whatever it is, is likely to be extremely conceited. “You are serving your interest, but I am serving the public interest.” Lofty expression; grave voice; large pension. And the problem with our entire education system at the moment, from school upwards, is that it seems to encourage people to opine and emote and genuflect in ways which involve ostentatious and positively Pecksniffian displays of concern for the greater good, the common weal, the public interest: though expressed not in Shakespearian or High Victorian manner but in the friendly and caring style of the CBeebies.

Of our three great candidates for a universal class it has to be said that the proletariat is out of favour. It is derided by academics and journalists — and sometimes both (Cas Mudde and Jan-Werner Müller keep popping up in the Guardian) — as ‘populist’. A dread word, ‘populist’: it brings to the mind of the average onion-emoting and lemon-opining educated liberal citizen a horrific Bosch vision of Donald Trump, Nigel Farage, Geert Wilders, Victor Orban and massed AFD types, indeed, everyone on the ‘far Right’ or ‘hard Right’, all making a merry hell of the world. So this leaves the other two candidates for a universal class: the intellectuals on the one hand, and the bureaucrats on the other. Those of us who get easily bored focus on the bright intellectuals; but McGrogan says that we should overcome our scruples, turn on the night vision goggles and focus on the dim bureaucrats instead: since it is their inertia and sense that they are right and their absolute inability to justify how they are right that forms the ‘immovable obstacle’ that is fatberging the sewer of the modern state. They make the intellectuals look like leaves in a windy autumn, easily dissipated.

Secondly, I wanted to talk about coup d’état. Everyone thinks they know what a coup d’état is. Surely it is an insurrection, an attempt to snatch power away from those who hold it? Surely it is the October Revolution of 1917? Surely it is January 6th? Well, it can be these. But it is actually something much more interesting than mere insurrection. For, as originally defined by the remarkable French writer of the early 17th century, Gabriel Naudé, it is not something which is done to a state, but something done by a state. A coup d’état, he wrote, is a coup inflicted by the state on the people. He said it was like the act of a god, a thunderbolt, a raining down of disaster, an Old Testament plague, a sudden blow.

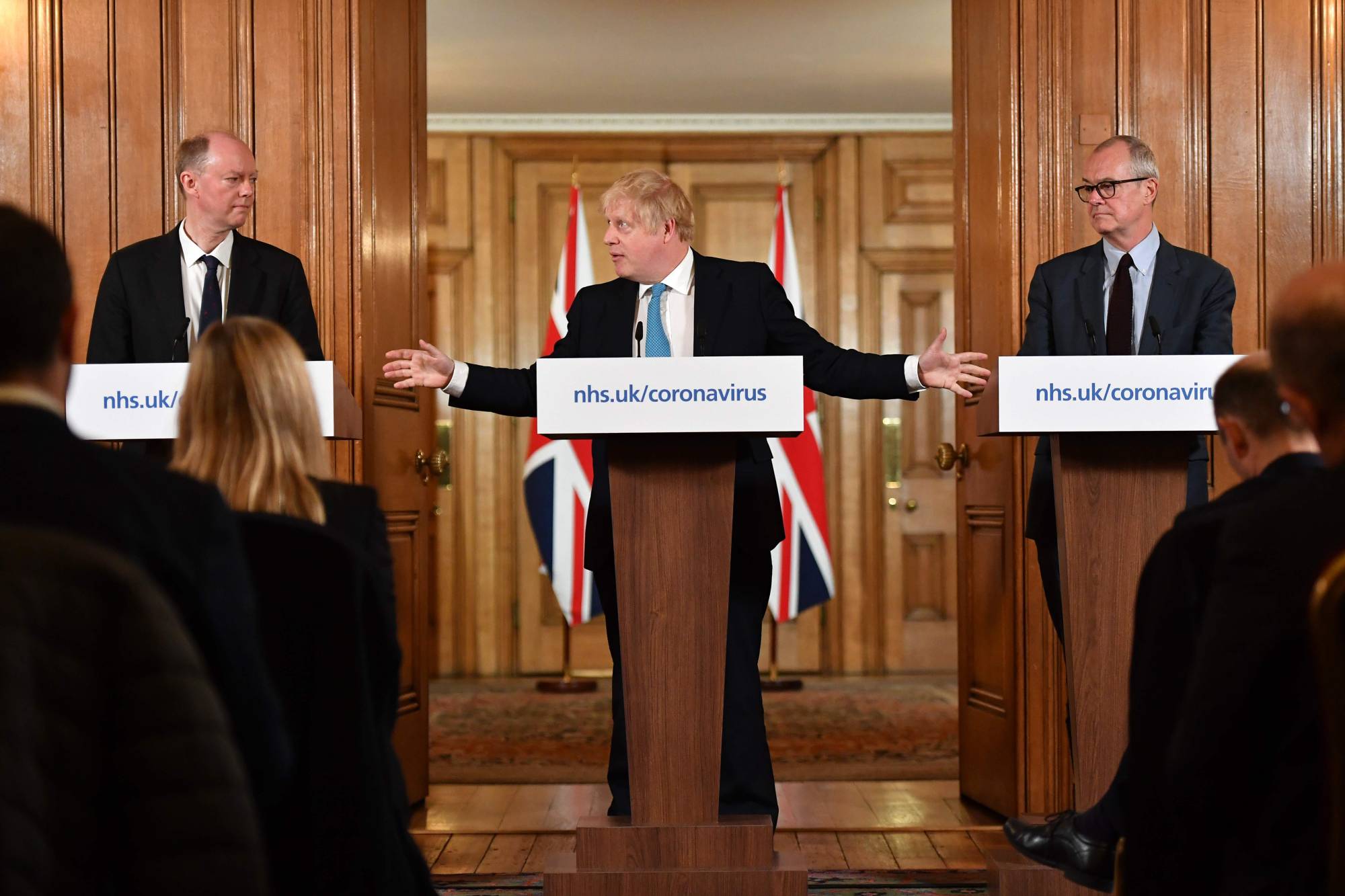

I submit that COVID-19 was a coup d’état.

So was accession to the EEC.

Modern politics could be considered death by a thousand coups.

Since I am littering this essay with capitalised concepts, let me reflect on two more. Thirdly, let us mention conspiracy theories again. If we suppose that Plato is right, and the state is founded on a ‘noble lie’; if we suppose Machiavelli is right, and politicians need to employ all the arts of force and fraud — lion and fox — in order to maintain their own state; and if we suppose that Naudé is right, and the state acts most decisively and mysteriously when it acts like a capricious god: then conspiracy theories are not the works of madmen but what Anthony Fauci would call “just common sense”. The modern academic and journalistic habit of deriding conspiracy theories is just one more way of concealing the arcana imperii by which our order is alchemised, cabalised and witch-doctored by our overlords.

Fourthly, it is perhaps worth saying something about Michael Gove’s recent redefinition of extremism. ‘Extremes’ are feared by those who think they are in the middle. The ones who think most pompously that they are in the middle — serving the public interest and not their own miscellaneous interests — are the members of the universal class. Any definition of extremism is an attempt to shore up a sandbank in a rising tide. Gove, whose speeches sound as if they come from someone whose onions and lemons have been helped down with great quantities of roast pork, madeira wine and linen napkin, tells us that Britain is stronger through diversity. That is a lie, obviously. The universal class is petrified, not only by the off-message ruminations of the many immigrants who have come in, but also by the off-message ruminations of the ‘populists’ who think that Britain’s natural and easy diversity of the last century or more is being displaced by an ironclad Orwellian discourse of diversity which is, in fact, anything but diverse.

The ‘deep state’, the ‘blob’, the ‘universal class’, whatever you want to call it, is trying to define something arbitrarily in the hope that it can hold the leaking sides of the ship of state together. But definitions are for schools, not for politicians. Gove’s redefinition is yet another gesture towards defending ‘British values’ which no one has ever believed in. Churchill didn’t believe in them; nor did Gladstone; nor Pitt; nor Walpole; nor Clarendon; nor Cromwell; nor Burghley; nor Warwick the Kingmaker; nor Montfort; nor Becket; nor Bede. British values are bogus. ‘Extremism’ is just an admission that the British state let the cats out of the bag in the last few generations, and is trying to find a few stray cats to rebag and drown in order to suggest that all is well in the world. It is yet one more coup d’état, even if only a relatively titchy one, by the universal class.

Dr. James Alexander is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at Bilkent University in Turkey.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.