The U.K.’s electricity supply is becoming increasingly reliant upon a series of umbilical cables to the continent called interconnectors. We have cables stretching to France, Belgium and other countries. Last month, a new £1.7bn 475-mile interconnector to Denmark was brought into operation.

Energy Secretary Claire Coutinho was lauding this new development on X. She said (emphasis mine):

The 475-mile cable is the longest land and subsea electricity cable in the world and will provide cleaner, cheaper more secure energy to power up to 2.5 million homes in the U.K.

It will help British families save £500 million on their bills over the next decade, while cutting emissions.

A deep dive into the National Grid interconnector data, however, shows the claims of cleaner, cheaper and more secure energy do not stand up to scrutiny.

They do not make it cleaner. The problem here is that the energy we import during periods of high demand is likely to be ‘dirty’ energy from diesel engines and coal-fired power stations, while the energy we export in times of lower demand is more likely to be ‘clean’ energy from wind and solar.

Second, it is crystal clear that interconnectors do not provide cheaper energy. In fact, quite the opposite is true. The data show that interconnectors have helped us to perfect the art of buying high and selling low. The price we pay for imports is consistently above the market price and the price we get for exports is significantly below market rates; we even frequently pay others to take surplus power off our hands (known as negative prices). In what world does it make economic sense for consumers to pay elevated subsidies to generate wind and solar power, and then pay people overseas to take the same power off our hands?

The security claim is more nuanced. In a narrow sense, the interconnectors do provide some security, because even though at times we pay excessive prices for electricity, the interconnectors have allowed us to keep the lights on. However, we are in this position because people like Alok Sharma gleefully blew up coal-fired power stations, so destroying our domestic dispatchable capacity. This means we are now dependent upon the kindness of strangers in Europe to keep the lights on. As other European countries continue down the path to Net Zero, destroying dispatchable sources (like Germany’s nuclear power plants) and installing more intermittent sources of energy, we may not be able to rely upon this kindness. Indeed, it is likely that Europe-wide electricity surpluses and deficits will synchronise as a result of seasonal and time-of-day related factors, meaning that there will be more times when we pay others to take our surplus power and we will pay extremely high prices more frequently when demand is high and renewables generation is low. Overall, this is clearly not a position of security, it is a position of weakness and insecurity.

Moreover, it is also clear from the data that we are a price-taker, not a price-maker in the market. This is because we do not have sufficient dispatchable capacity to meet demand. Again, this is a position of insecurity, not strength.

The detailed analysis below demonstrates clearly that Coutinho’s claims are bogus.

Volume and Value of Electricity Traded Over U.K. Interconnectors

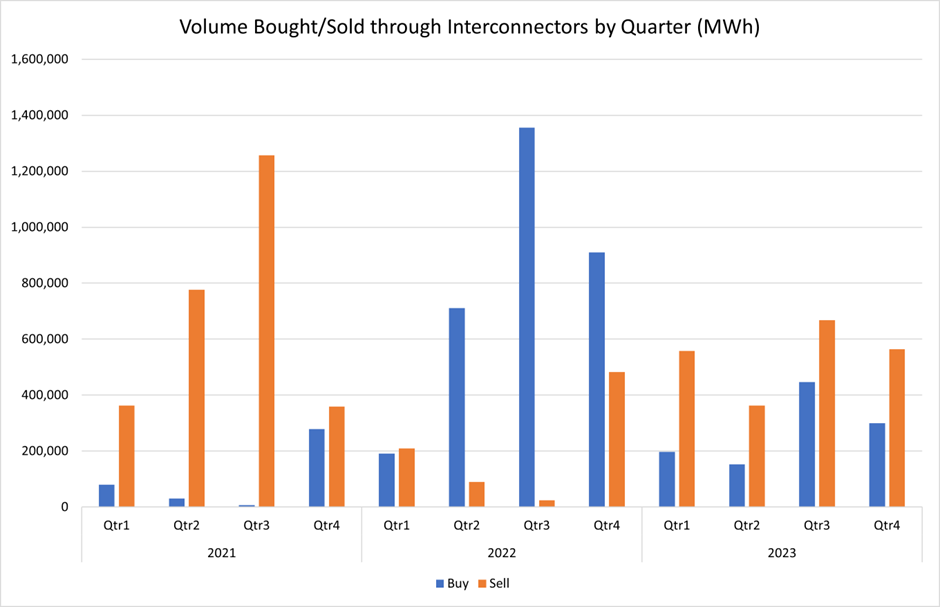

Figure 1 shows the volume of electricity traded over the interconnectors by quarter for the years 2021-2023.

In 2021, we sold far more electricity (2,756 GWh) than we bought (396 GWh) over the interconnectors. In 2022, the position reversed, and we bought (3,168 GWh), which is far more than we sold (805 GWh). In 2023 the situation was more balanced, and we sold more than twice as much (2,152 GWh) as we bought (1,097 GWh). It appears that the third quarter of each year always sees the most total trade.

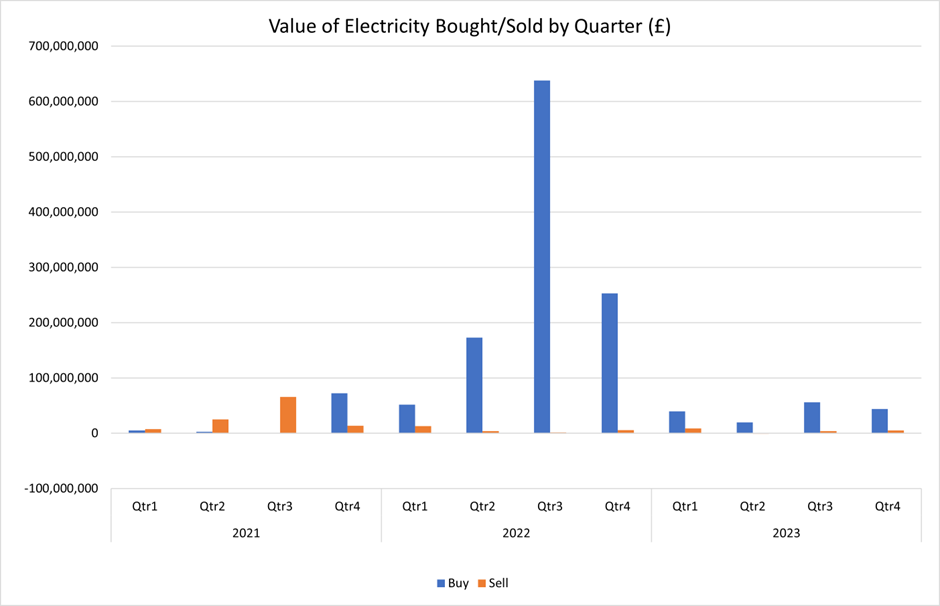

Figure 2 shows the value of electricity traded in the same periods. The total value of the trades is calculated by multiplying the volume traded in each auction by the volume weighted price. As we shall see below, sometimes we pay people on the continent to take power away, making the price is negative for some sales transactions. When the data are aggregated, this has the impact of reducing the apparent sales value.

In 2021, even though we sold far more electricity than we bought, the value of the trade was more even with £112m of sales and £82m of purchases. 2022 was an exceptional year with £1,116m of purchases and only £25.2m of sales. In 2023, even though the volume sold was double the volume we bought, perhaps surprisingly there was a much higher value of purchases (£160m) than sales (£16.7m).

Electricity Interconnector Transaction Prices Compared to Daily Market Prices

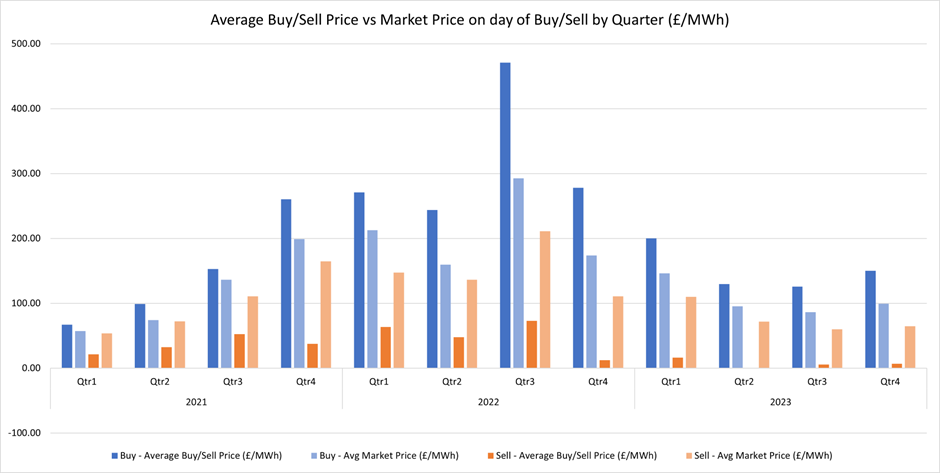

Figure 3 compares the average price of purchases and sales through the interconnectors to the market price of electricity on the day of the transaction. The Low Carbon Capture Company publishes a dataset that shows the subsidies paid in relation to various renewables through CfDs (contracts for differences) each day. That dataset also includes the Market Reference Price for wind and solar on each day which has been used as the market price for each day. Typically, this reference price is set by gas-fired electricity.

The dark blue bars show the average buy-price in the quarter. The light blue bars show the average of the market prices on the day of the transactions. The dark orange bars show the average sell-price in the quarter and the light orange bars the average of the market prices on the day of the transactions.

The bottom line is that we typically pay more than the market price for buys (the dark blue lines are taller than the light blue lines) and accept less than market price for sells (the dark orange lines are shorter than the light orange lines). Looking at the detailed data, the maximum purchase price was £6,599.98 per MWh on July 20th 2022 when the reference price was £247.91 per MWh. The minimum sale price was £–404.71 per MWh on May 29th 2023 when the reference price was £63 per MWh. It is also interesting to note that for the whole of the second quarter of 2023, the average sale price was slightly negative (£–0.22 per MWh). These negative sales prices mean we paid others to take this electricity off our hands.

Frequency Distribution of Electricity Interconnector Buys and Sells

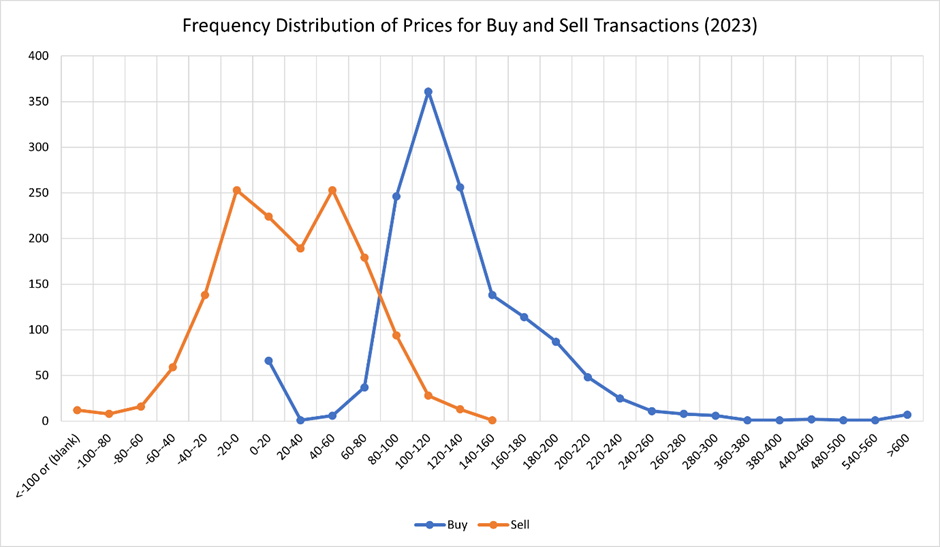

Figure 4 shows the frequency distribution of buy and sell prices for 2023.

As you can see, we have perfected the art of buying high and selling low. A sizeable proportion of the sales transactions have a negative sales price. The peak is in the £–20 per MWh to £60 per MWh range. Most of the interconnector buy transaction prices are above most of the sales prices, with a very wide spread that peaks around £100 per MWh. However, there is a cluster of buys in the £0-£20 per MWh range and a sizeable number of buy transactions over £600 per MWh.

Interconnector Buys and Sells by Time of Day

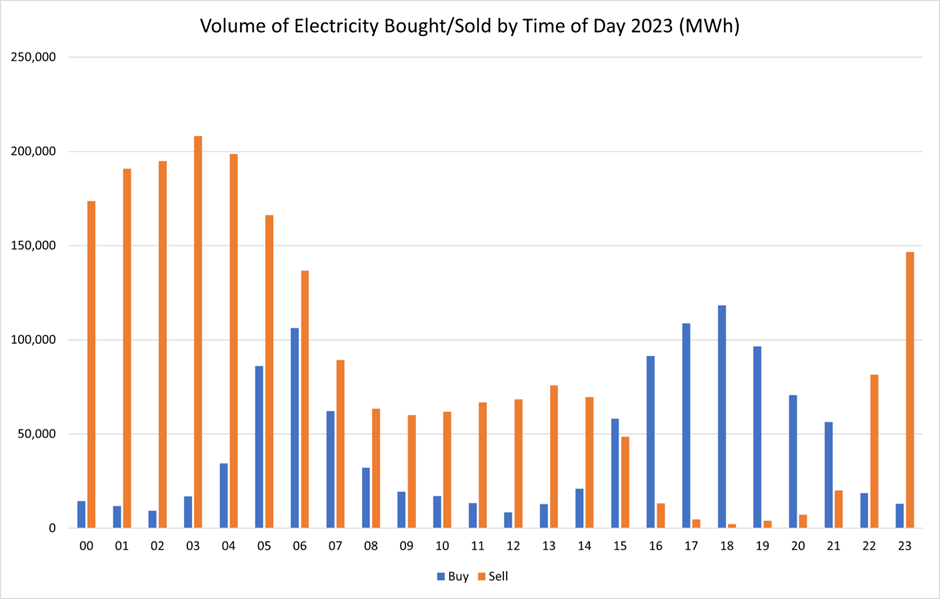

It is also instructive to look at the volume of electricity traded by time of day. Figure 5 shows the volume traded in 2023 by time of day.

As we can see, most of the electricity sold is from 10pm to 6am. There is also a residual tail of sales from 7am to 2pm, reflecting the demand lull in the middle of the day. Most is bought in the morning peak from 5am to 7am and then again during the evening peak from 4pm to 9pm.

As might be expected, we are selling most when demand is low and buying when demand is high, reflecting the fact that we are not really in control of generation and cannot use it to match demand.

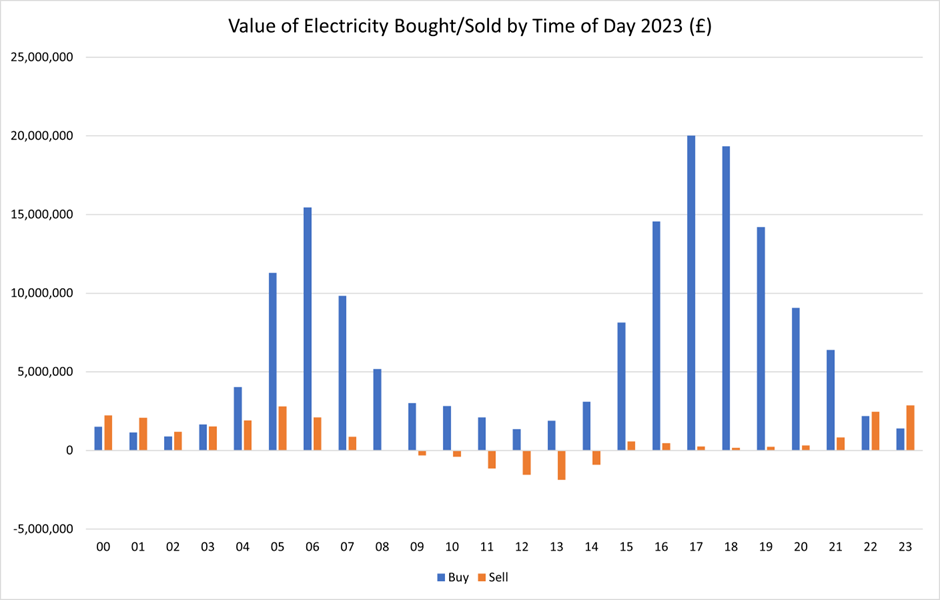

This is further illustrated by Figure 6 that shows the value of electricity traded by time of day.

Even though the volumes sold during sleeping hours are high, the value of that electricity is low. In aggregate, the electricity sold during the middle of the day has negative value, so we pay others to take it off our hands. By contrast, we pay through the nose for the electricity we buy at peak hours.

Conclusions

Evidently, there is a massive disconnect between the rhetoric about interconnectors and the reality. Sadly, it is becoming clear that in many cases, when it comes to pronouncements involving Net Zero, the opposite of what the Government tells us is true. They are not cleaner – we tend to buy ‘dirty’ electricity and sell ‘clean’ electricity. They are not cheaper – we are being ripped off at every turn. And they are not more secure – we are dependent on our neighbours being willing to sell us electricity at times of scarcity.

The interconnectors are a giant swindle. They are nothing but an expensive sticking plaster over the reckless mismanagement of our dispatchable generation capacity. This can only be solved by investing in new sources of dispatchable supply (like gas and nuclear) so we can regain a position of strength. This investment would increase energy security, make us a price-maker in Europe and turn the interconnectors from an expensive liability into a valuable asset.

David Turver writes the Eigen Values Substack page, where a longer version of this article first appeared.

UPDATE: This article analyses only the National Grid auctions for trade of electricity across the interconnectors. Additional energy is traded across the interconnectors as detailed by Elexon, where the picture may be different. This may be the subject of an additional article.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.