A strange intervention has given another twist to the farce of the Benin bronzes. Nigerian Prince Nosuyi Ovonramwen has suggested in a blog post that “descendants of the slaves” (referring to the ones Benin sold) should be allowed to “share in the value of the bronzes”. Surely, a call to sell up and distribute the proceeds?

A British expedition of 1897 overthrew Oba (King) Ovonramwen and his regime in Benin, which still gloried in mass human sacrifice of slaves and war captives. Slaves were freed, the mass murders stopped, and Ovonramwen’s son was reinstated in 1914, with his line continuing to today’s essentially ceremonial Oba Ewuare II. Prince Ovonramwen, who lives in Nigeria, is the overthrown Oba’s great-great-grandson, which is why his opinion carries weight.

Thousands of bronze, ivory and wooden artefacts were removed from Benin in 1897 and ended up in the world’s museums, the bronzes widely admired for their sophisticated casting, evidence of unsuspected artistic skills in Africa in the Middle Ages. Until March this year, Nigeria’s campaign to get the artworks restituted was going nicely, with well-intentioned (or colonial-guilt-obsessed) curators and trustees handing collections to Nigeria’s Museums Commission (NCMM, that is, the Nigerian people): Jesus College, the Smithsonian, London’s Horniman Museum, and most spectacularly, 1,130 of pieces in Germany’s state museums – with more in prospect.

As the Daily Sceptic reported on May 15th, Nigeria’s President quietly decreed in March that everything restituted to the NCMM would in fact be handed to Oba Ewuare, as his private property: past auction records show these pieces have huge market value, the record currently standing at £10m for a bronze head. The President’s bombshell brought restitutions to a halt. Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology had a rethink only days before handing over more than 100 pieces, and German curators and politicians have tried to face down the uproar (only a couple of dozen pieces having left Germany so far).

It remains to be seen what these trustees and curators will make of a Benin Prince’s idea that their museums’ works should now be sold by Nigeria and the money handed out. Nothing of what has already been restituted has been seen by the Nigerian people, and no-one will say where those works are today. Three important ones, stolen from Lagos Museum some years ago, ended up in New York’s Met Museum, but after having been sent back yet again they’ve vanished.

Meantime the Restitution Study Group, speaking for millions of American and Caribbean descendants of the slaves whom Benin and other African kingdoms sold, is gaining support for its claim that the bronzes should stay on display where they are, around the world, as memorials to the sufferings of their ancestors and to shame those who captured and sold them to foreign traders.

Professor Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin wrote in May about the shambles of the restitution process from a German viewpoint and on August 6th she published another trenchant article in Neue Zürcher Zeitung, saying that the post-colonial debate has been missing the point – the ‘victims’ are not the Benin kingdom, but its slaves; and that as slavery was abolished slave owners in British and French colonies were handsomely compensated – she gives surprising figures – but the slaves themselves got nothing.

She ends by arguing:

The recent history of the bronzes has been accompanied by a change in meaning: as the embodiment of ancestors, they were persons, instruments of power and objects of worship. But with the British subjugation of Benin they lost their sacred character; they became spoils of war, commodities to be sold on the art market and private property. A large part ended up in public museums around the world as cultural assets, where they became what they are today: a first-class cultural World Heritage.

All those whose actions and suffering are embodied in the artefacts have rights to them. They and all those connected to them – indeed, all of us – are entitled to co-ownership. It is time to give up the exclusive concept of private property of cultural assets in favour of a communal concept of ownership. ‘Shared heritage’, in other words.

It’s worth reading in full, she demolishes the idea that the Benin works are nothing more than stolen private property.

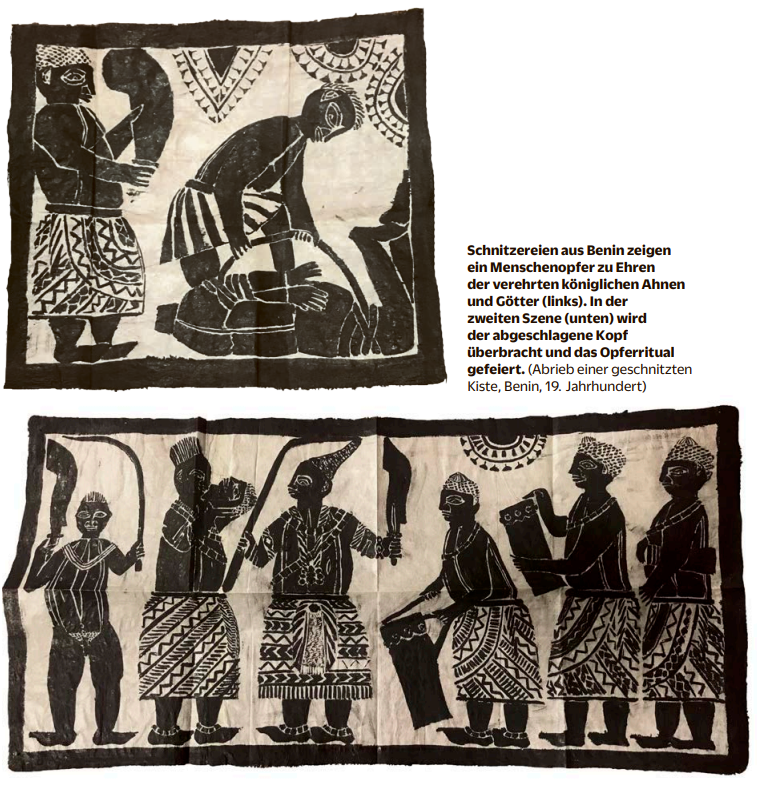

Hauser-Schäublin’s article is headed by pictures of a carved wooden box from Benin which she noticed in Hamburg’s MARKK Museum. It glorifies human sacrifice. On one end, an executioner brandishes his sword over a headless corpse with bound legs and arms; on the lid an official displays a severed head while drummers celebrate.

But images like this from Benin itself, giving the local view of what went on there, might vanish from the world: the Smithsonian is among museums which have handed to Nigeria image rights in artworks along with the pieces themselves. The Obas have never apologised for their ancestors’ murderous, slave-trading past: why would they want the world to see the evidence?

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Apart from a very short period in spring 2020, which would probably have been detected and reported on, I can’t see much evidence of anything unusual of significance happening. If “covid” had not had such a large advertising budget, no-one outside specialists in the field would have talked about it beyond the odd report/remark about a bad flu season.

Quite. One would assume that all other respiratory viruses that we’ve co-existed with forever had ceased to exist. Also, don’t ask me why but I happened upon this. Perhaps I’m being dim but where is the mention of Coronavirus here?

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/respiratory-virus-circulation-england-and-wales/six-major-respiratory-viruses-reported-from-phe-and-nhs-laboratories-sgss-in-england-and-wales-between-week-1-2009-and-week-23-2019

Indeed. Not only Covid, but all of the other coronaviruses (i.e. common cold coronaviruses) are also missing from the chart as well. That could not have been just an oversight.

I wonder what the graphs looked like when we just had ‘a cold’…

Or had they ran those PCR samples at a more appropriate cycle threshold, which I believe was in the vicinity of 25 Cts, as opposed to 40+ Cts.

https://swprs.org/the-trouble-with-pcr-tests/

I can recall many times where a cold was ‘going around’ and many people we were in contact with would catch it, deal with it and think nothing much about it. It was literally just ‘going around’. We had no idea if 10 people had it or 10,000 people, and it mattered little. Lemsip at night, two Paracetamol and off to work in the morning. Why do we have teams of statisticians churning out graphs for us to see. I don’t need a graph. Stop it..!

Well-said. Especially for kids and young people, this virus is really just a little pest for the most part now.

Correct. I too fail to see the need to even be talking about this all it does is help keep the frenzy alive and of course the experimental clot shots going. Madness pure madness.

So true. PCR testing at such high cycle numbers is blatantly misleading, if not utterly fraudulent.

Indeed, these graphs are precisely what one would see for the common cold this time of year (beginning of school year). That is, if cold viruses were ever tested for with anywhere near the same zeal as they do for Covid (which, much like the old coronaviruses that came before it, has basically become the new common cold these days, especially for kids).

Here’s something on the effect of boosters and jabs in general in the 65+ year olds. I compare weekly deaths working age 20-65 and retired age 65+. On the chart, I have added some jab milestones. (Note that the last point is for a week with a bank holiday and needs to be considered in conjunction with the next week or two).

You can keep reports on covid ‘testing’. The only testing that does is to test my patience with adherence to this bogus indicator.

These ONS number are still meaningless bullshit. They’re meaningless because Sars-CoV2 RNA fragments detected is not a medical diagnosis of anything. And they’re bullshit because Sars-CoV2 RNA fragments aren’t randomly distributed among the population, hence, testing a random subset of it bears no inherent relation to the actual distribution of Sars-CoV2 RNA fragments among the population. As they’re also not statically distributed among the population, the ONS numbers would even be bullshit even if the original property was randomly distributed.

Isn’t about time for another article on how melting sea ice doesn’t reliably correlate with the number of children born in Cardiff or some other plainly unrelated issues like Vaccination doesn’t preven infection!?

“Covid infections”! Oh dear, Will Jones using the terminology of the enemy again. Using the fraudulent term “vaccines” is bad enough when talking about these novel Covid jabs. Now do I really have to run around the interweb ( actually, no need. It’s probably all on here! ) citing studies which show that a positive PCR is hardly evidence of ‘infection’? That many hypochondriacs who have zero symptoms but test positive using a hyper-sensitive tool which could find any insignificant fragments when amplified high enough and that was never intended for use in diagnostics is proof that somebody has an infection or is infectious? You might have at least said “positive test results” as opposed to “infections”, Will. Disappointing.

Plus there is some evidence that under UV light, the result of the ‘test’ is predetermined….

Oh really? I haven’t heard of that before. I heard something about them being unable to distinguish Covid from flu but I don’t know if there’s actual truth in that. It would be a handy explanation of what happened to the flu though.

What is COVID?

Is it a life threatening pulmonary disease?

Or is it a mild to moderate cold?

Well it certainly ain’t an emergency, therefore having these bivalent boosters authorized under yet another EUA is really just a massive p*ss-take and milking this cash-cow of a scamdemic for all that it’s worth. Talk about corruption and greed…”emergency” my arse!

As time goes on, it is becoming less and less like the former, and more and more like the latter.

How do they even know the numbers?

I wonder that too. In Scotland most of the figures are a result of modelling. There are allegedly people who are monitored but I’ve never met anyone.

I’m amazed at the number of people who are still testing themselves whenever they get sniffles. I imagine they see themselves as virtuous members of society.

>In Scotland most of the figures are a result of modelling.

Seriously? I thought we’d put the accuracy of modelling well and truly to bed?

Accuracy is not what is wanted, it seems.

A little bump in the beginning of the school year, that burns out within a couple of weeks, basically.

Children acting as a hub of infections at the start of the school year? Quelle surprise – not!

I suppose there will be a massive surge of alleged ‘infections’ over the coming weeks due to all those people attending the events associated with the death of Queen Elizabeth.

The ‘poor’ corrupted NHS will beseech for the mandates / restrictions to be reintroduced to help it cope – badly, as usual – with the

predictableannual ‘winter crisis’…The return of our old frenemy, the flu, has already happened in Australia. So the USA and UK (and the entire northern hemisphere) should be next as the seasons change.

conversation about so-called ‘covid’ is often much like arguing about how many angels might fit on the head of a pin. such conversation is often semantically ludicrous, because ‘covid’ cannot be diagnosed clinically – there are no pathognomonic features; and because the ‘covid’ test commonly used for diagnosis, the PCR, is usually fraudulently upcycled to a point where most ‘positives’ are false; and even genuine PCR ‘positives’ cannot distinguish between actual infectious viral illness, and random nucleic acid sequences originating from any old goat or papaya (RIP John Magufuli, Hero Of The Resistance). when conversation about ‘covid’ refers to covid data with no reference to these issues, these fundamental frauds degrade the probity of all such conversation, in accordance with Lord Denning’s 1956 judgement that fraud vitiates everything it touches.

“…but the data for other age groups show that over 80% of 17-29 year olds in England have natural immunity…” (My emphasis)

Do they really mean natural immunity as in having had Covid and having produced antibodies without any recourse to vaccination? If so why are we still being encouraged to have the vaccines?