Jessica Rose is obviously more pleasant and less censorious than some of the other commentators who have been trying to ‘debunk’ the suggestion by a group of German scientists that the ‘yellow’ batches in the recent Danish Pfizer-BioNTech batch-variability study could be placebos.

But her own ‘debunking‘ has one obvious problem. Her criticism focuses on the claim that the ‘placebo’ batches actually have many adverse events associated with them, just not in Denmark, where the study was focused. However, the denominators she uses in order to compare the rates of adverse event reports per batch that turn up in VAERS have been chosen arbitrarily.

She says so herself. Thus she writes:

It is important to note that I do not have the ‘doses’ (dose number) for the relevant yellow vax lots as per the VAERS data. It is a pity. If I had these data, I could provide a much better analysis. For the purposes of this analysis, I assume that the batch sizes per lot are equal [to those in the Danish study]. This might be a very bad assumption, but what can I do? I’m still better than the CDC staff, combined.

But if we do not have the number of doses, what is the point of the comparison? Nobody has ever claimed that there were no adverse event reports associated with these batches. In the Danish study, there were in fact four ‘yellow’ batches that had literally zero adverse events associated with them. But the other 14 merely had relatively few. The issue is the reporting rate.

Moreover, the problem is even more serious. As seen in the above quote, Jessica Rose simply assumes that the appropriate denominators for the VAERS reports are equal to the denominators in the Danish study, i.e., the number of doses of each batch deployed in Denmark. But we do in fact know the total number of doses included in the batches in question, and, unsurprisingly, it is far higher. Why unsurprisingly? Well, because the whole is greater than the part.

As discussed in my previous article, these are EU batch releases falling under the authority of Germany’s Paul Ehrlich Institute (PEI) as the responsible regulator. Needless to say, the number of doses deployed in just one – moreover, small – EU country is usually going to be less than the total.

In his interview with Milena Preradovic (which is the source of the entire controversy), the German chemistry professor Gerald Dyker notes that, per information provided by the PEI, the total number of doses contained in a batch or lot was “a little less than 1.4 million”. Assuming batch releases have been consistently of this volume, this means that the actual number of doses in the EU batch releases is anywhere from nearly three times (FH8469) to nearly 20 times (FM3289) the totals assumed in Jessica Rose’s analysis.

Redoing the analysis with the appropriate denominators would presumably make most or all of the ‘extra’ adverse events reporting that Jessica Rose discovered in VAERS disappear. The total number of reports would remain the same, of course, but they would now be associated with a far higher number of doses. I will leave it to others to undertake the exercise if they see fit.

Jessica Rose appears not to have been aware of the whole-and-part issue in conducting her analysis, i.e., that Denmark is in fact part of the VAERS sample. She thus notes in a footnote that none of the relevant reports in VAERS originated from Denmark. But what she is saying, more precisely, is that none of the reports are listed as having originated from Denmark. This is because almost none of the relevant reports contain any information on filing location at all.

Not surprisingly, since these are EU batch releases, they are almost all foreign (i.e., non-U.S.) reports, and the location simply appears as such – ‘foreign’ – in top-level VAERS searches. But what is interesting to note is that when Jessica Rose did a search for filing location using a more advanced (‘split type’) search parameter, she came up with just a few far-flung locations like Brazil, Montenegro, Japan, Moldova, etc. – but not a single EU country! These are EU batches. So, where are the EU countries? In fact, they are undoubtedly all the rest of the reports.

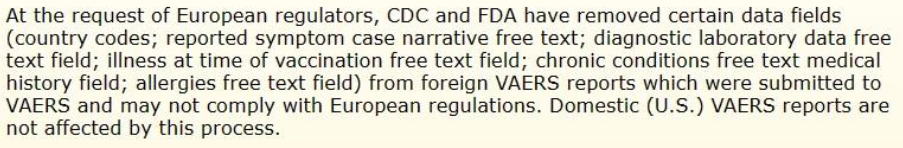

Why then would they not be listed as such? Well, it will be recalled that last November, on the request of ‘European regulators’, VAERS was purged of EU data. The purged data includes precisely the country codes. See the below notice, which comes directly from the CDC website.

This is yet another of many reasons why VAERS is an extremely blunt instrument to use to try to validate or invalidate the results of the Danish researchers. VAERS is not a ‘global’ reporting system. It is an American reporting system, which, under specific circumstances, also includes foreign reports which the manufacturers are required to forward to it.

The way to try to validate or invalidate the Danish results is not by digging around in the highly fragmentary VAERS foreign report data, but rather the old-fashioned way dictated by the scientific method. Other researchers in other, preferably EU, countries with access to comparable and similarly complete data, including both adverse event reports and number of doses deployed, have to try to reproduce the results.

It is worth stressing that it is precisely due to the intervention of unnamed ‘European regulators’ that the VAERS data are even more fragmentary and unhelpful than they would otherwise have been. And it is none other than the release of the batches by one very important European regulator, Germany’s Paul Ehrlich Institute, that is at issue in this whole affair.

For, as Gerald Dyker revealed in his interview with Milena Preradovic, not only did the PEI approve all the very bad blue batches for release, it did not even bother to perform quality-control testing on all-but-one of the seemingly very ‘good’ yellow ones. It was this fact – not the Danish study per se – that led Dyker to suggest that there might indeed be something to the placebo hypothesis.

Finally, Jessica Rose also claims to have provided support for the theory that the Danish findings are merely a result of undetected age-confounding. Thus, she compares the ‘worst’ blue batch in the sample to one randomly chose yellow batch and finds that the mean age of the blue-batch recipients is significantly higher than the mean age of the yellow-batch recipients.

It should be noted in passing that by choosing the ‘worst’ blue lot, she has obviously biased the outcome of the comparison. After all, the very premise of the exercise is that we should expect to see more adverse event reports the higher the age.

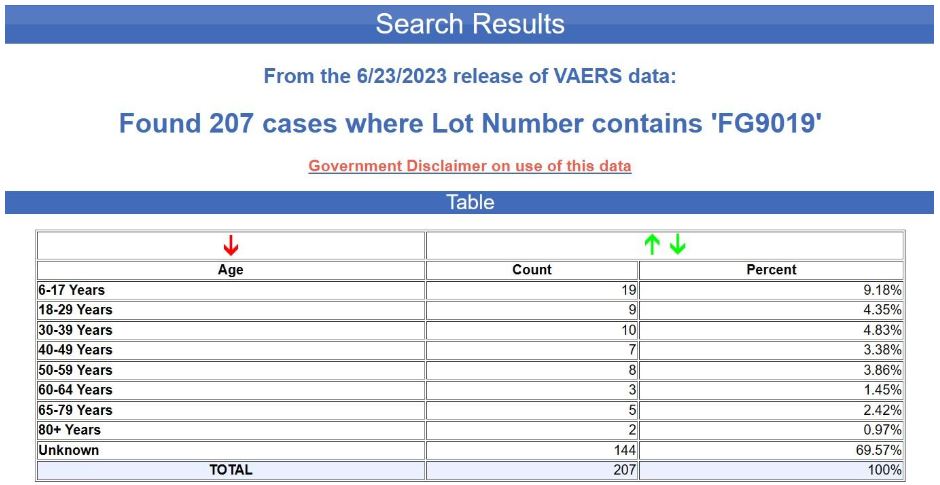

But even supposing that this bias were corrected by including more lots or using more comparable lots, the more fundamental problem here is again the extremely fragmentary character of the data. In fact, the age of the recipient is not even indicated in the overwhelming majority of the reports in question. The tabular search results for the yellow batch (FG9019) are shown below. The age is unknown in nearly 70% of the cases.

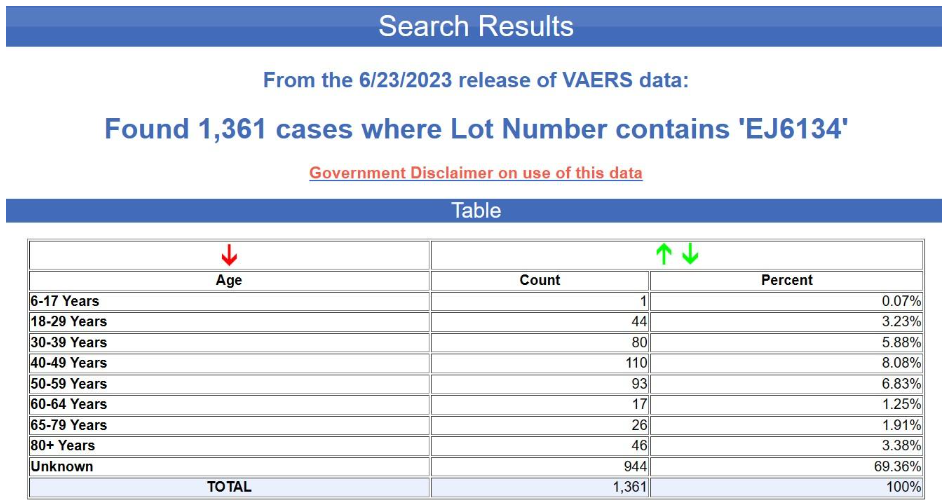

And here are the results for the blue batch (EJ6134).

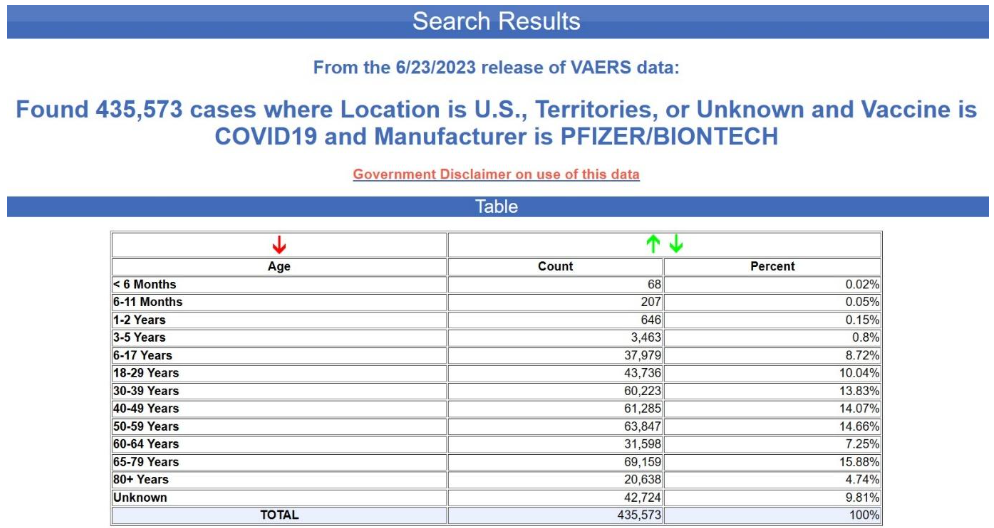

Yet again, the age is unknown in nearly 70% of the cases. This is not at all typical for VAERS, by the way. Below is the age distribution for all the adverse events reports for the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine excluding the foreign reports i.e., for U.S. reports only.

The age is unknown in only 10% of the reports. Although not acknowledged in the CDC notice, it would appear that the recipient’s age has also been scrubbed from most or all of the EU reports. How can one draw conclusions about age-confounding using a database from which most of the age data have been scrubbed?

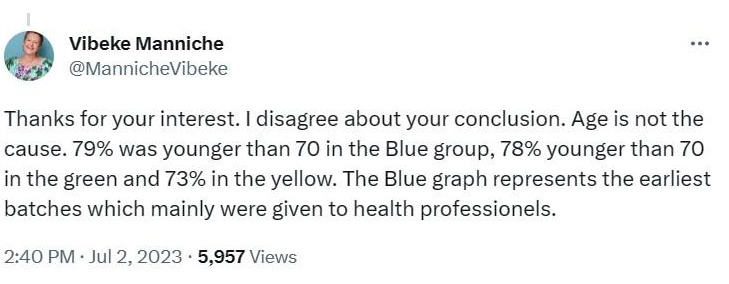

In any case, if one suspects that the batch variability in the Danish study is just a function of the ages of the vaccinees, why not ask the authors if they have relevant information? As it so happens, they do, and Vibeke Manniche, one of the authors, has addressed the issue in the below tweet reply to Denis Rancourt. The reality is exactly the opposite of what is suggested by the age-confounding hypothesis: more elderly people got the ‘safe’ yellow batches than the dangerous blue ones.

Robert Kogon is a pen name for a widely-published financial journalist, translator and researcher working in Europe. Subscribe to his Substack and follow him on Twitter.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

And Sasha Latypova thinks that they aren’t placebo, so the plot thickens;

”Does this prove the “yellow” batches are placebo?

Not really. Caution is required when interpreting these data. The German authors did not say these are placebo, but rather that they look “something like placebo”. They also noted that in vaccine studies “placebo” can contain all adjuvants and other “inactive” ingredients. We know from declared ingredients on vax labels those are completely novel lipids not properly disclosed (proprietary), and actually harmful substances (such as PEG).

My own guess is that the yellow vials might have contained “empty” hydrogel formulations (or LNPs, which might be the same thing), and the green and blue – some combinations of nucleic acid based materials added, including plasmid DNA “contaminants” and endotoxins. Many vials tested by the independent groups found a variety of contaminants – most frequently toxic metals and objects from nano- to macro-scale. Some groups state they found graphene oxide, and I am not a specialist in this analysis to confirm their findings. In any case, this requires mor verification.

The journalists and podcasters that spread the message changed that to a more definitive statement of “placebo” which is unfortunately not accurate.

These batches show up in adverse event reports, so they were associated with at least some adverse events. Therefore they are not saline. Furthermore, no pure saline vials have been found in the independent vial testing that I am aware of. So, caution is warranted. The “yellow” batches appear to be less toxic overall, but we still do not have a full picture on the vial contents, and a full transparent investigation is needed.”

https://sashalatypova.substack.com/p/was-it-30-placebo

Yes..I’ll throw this one in as well…

https://geoffpain.substack.com/p/urgent-please-remove-all-reference

By using multiple sources of public data and logic we can build a more complete picture, so that the 3,913,960 Placebo jabs Danish fantasy can be conclusively laid to rest.

“These batches show up in adverse event reports, so they were associated with at least some adverse events. Therefore they are not saline.”

It would be expected for there to be some events reported even after treatment with a placebo.

The main point might be that the lots, batches, of these junk poisons had no uniformity in manufacture. ‘The Science’ can not elaborate on the manifests by lots, batches or ingredients across the same, and state that they precisely match. Therefore they were never tested for safety. As Schwabb the slap head-freak said in his ridiculous book Covid-19, the probem is not ‘The Science’, the problem is manufacturing and distribution of billions of these quackcines.

How can the MRHA et al tell us ‘safe and effective’ if they don’t know what is in the vials? They and Dr Quack and Nurse Tik Tok, had and have, no idea what the mainifests are, and cannot tell me that in my city, in my local-stabbination centre that Lot x, batch y and vial z were thoroughly tested and here Mr-Anti is documented proof of that safety analysis. Nothing. F’em.

Too much info there for me , I’m still stuck on the glory hole story !

Come on Freddy don’t go spreading mis or disinformation! It’s a Bonus hole, not a glory hole!

There is a huge debate going on at the moment..because Robert Kennedy recently said that no childhood vaccines in the USA had gone through gold standard placebo trials before being given licensing….

The debate has mainly focused on what a ‘placebo’ actually is or should be….so when someone mentions the word Placebo….it’s not really a given that everyone thinks it’s the same thing…or that it is, in fact what most of us would term a placebo….

Jessica Rose will be able to argue her own case I am sure..but this article makes it appear that she was trying to ‘debunk’ the study…which couldn’t be farther from the truth.

“By the way, this analysis in no way minimizes or undermines the findings in the Schmeling et al. study. They are absolutely right-on about those groupings, at least in the context of the blue and yellow groups. Hashtag: thegroupingsarereal.”

Isn’t this what it should be about..for all of us?….asking questions and making observations…not accepting something on face value….this will surely lead to the right ‘answer’….?

From my understanding the placebo used in the Covid trials was another vaccine – The meningitis vaccine.

“About half of the people who get a MenACWY vaccine have mild problems following vaccination, such as:

So no surprise there.

“If they occur, these reactions usually get better on their own within 1 to 2 days. Serious reactions are possible, but rare.”

Rare is, of course, subjective.

“I can confirm that the MHRA has received 1841 spontaneous UK suspected adverse drug reaction (ADR) reports concerning administration of the meningococcal A,C,W135,Y vaccine, “

Having read this, rather than whether or not the Danish report is evidence of a placebo, I’d like to know exactly why the “EU regulators” insisted that country data be kept out of VAERS.

Was it because it would show up too clearly the differences in countries that were more reticent on giving a gazillion doses and ceasing the recommendation for stabbing those under 18 (the Scandinavian countries were the first to slow down)? To avoid comparisons between the highly jabbed countries and those less inclined to roll up the sleeve? Or a comparison between those that had initially used more of the adenovirus-based vaxx rather than the mrna poison?

Did the EU regulators make this request following some nudging by the pharma-owned US authorities, who feared that some in the US might wake up and ask why an EU that was not stabbing 6-month old babies or handing out dose 310 was doing no worse than the US? The current Brussels administration is clearly in thrall to the current WH administration, so would probably be more than happy to comply, particularly as it needs US LNG to try to stave off the EU’s disastrous ‘energy transition’. And Ursie is probably more than happy to help her buddy Albie to keep pumping sales, 10% here, 10% there, every little helps.

Very good point. The deliberate obfuscation of data, or failure to collect obviously relevant data in the first place, has been a consistent feature of the whole shitshow. The “deadly pandemic” which resulted in nothing useful being learnt about the “virus”, ditto nothing learnt about the “miracle vaccines”.

All vaccines contain adjuvants to enhance the immune response to the active ingredient. It is these which usually result in adverse reactions.

The placebos used by Pfizer et al had these adjacents – and according to some sources inactive, harmless virus – precisely so that adjuvant-related adverse reactions would not just occur in the active ingredient group.

It is therefore not surprising that suspect placebo batches had adverse reactions reported. The question is what kind of reactions?

As emphasised by Dr John Campbell, the most concerning finding of the study is the extraordinarily high incidence of SAEs in the blue batches. Let us not lose sight of that.

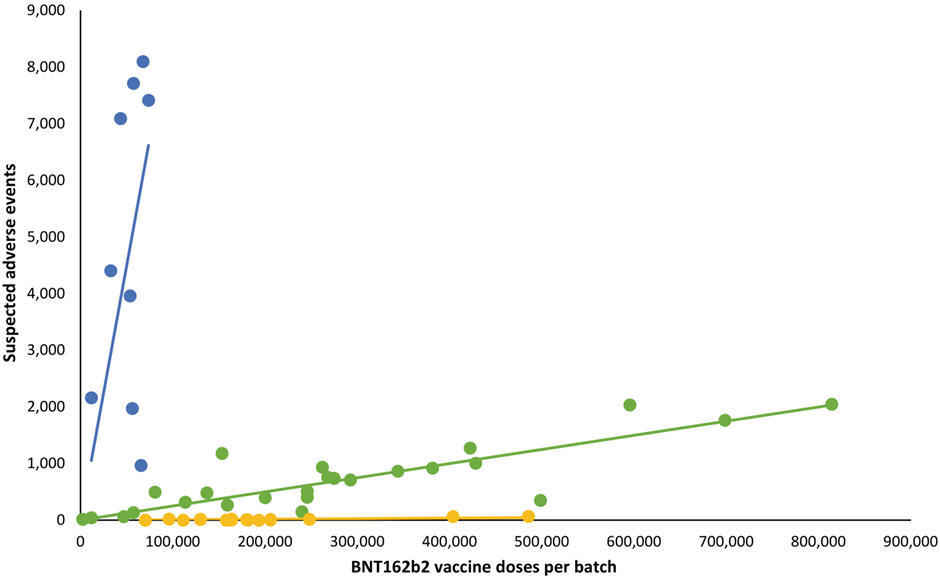

Very interesting. But can anyone help me understand a basic (statistics) point? How is the decision made to draw three trend lines on a scatter plot, rather than any other number?

Imagine the plot of the dots alone. It appears that a single trend line cannot be drawn. But, once the blue line has been drawn, surely the remaining dots could be fitted with a single line?

Are there some defined criteria to determine the ‘colour’ of each dot prior to fitting the trend line?

I’ve read several of the articles referenced here and elsewhere but can’t find an answer to this.

Isn’t the relevant question about the Covid outcomes from the different batches. I suspect these were no different (i.e. no difference in rates of sickness, hospitalization and death), in which case the real scandal is that the vaccines do nothing EXCEPT harm the recipient.

I don’t know about anyone else but what I would really like to know is who had the least damaging batches and the most damaging batches? I have a suspicion the least damaging, perhaps Placebo’s, went to Politicians. It’s quite strange that, as far as I am aware, Politicians, of which there are one hell of a lot, have not been dropping dead from heart issues like footballers and ordinary Plebs.

Given the extraordinarily high numbers of adverse events how can it be that none derive from Politicians and the Great and Mighty?

Yes I want to know that information too – apart from Boris’s trip to hospital did any other politician end up there?

There is a genuine misunderstanding of “placebo” here. Most people assume a placebo will just be saline or some other harmless substance, however vaccine placebos contain the same amount of adjuvant as the Covid “vaccines”. Therefore it is hardly surprising there are side effects, adjuvants are there to provoke the immune system

The important feature of the VARES data is that there were thousands of reports of adverse reactions and yet the jab was not withdrawn immediately! It seems that it has been in the UK except for the old, but 2 years too late. Use this to understand how bad the regulators really are, or it is likely that the decisions were political not medical!