Nigeria’s President has scored a dramatic, but surely unintentional, own-goal in that country’s long-running fight to extract Benin bronze castings from the collections of Western museums.

In the closing days of his presidency, President Muhammadu Buhari has signed a Presidential Decree transferring ownership of all restituted Benin artefacts from his Government’s National Commission for Museums & Monuments (NCMM) to the Oba (King) of Benin, as his personal property.

This torpedoes the narrative of well-meaning trustees and curators that they’ve been returning “to the Nigerian people” ancient bronzes taken from Benin in 1897 by a British expedition. When on December 20th German foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock headed a large delegation to Abuja, she handed over a second small batch of the 1,130 pieces her country’s five leading museums gifted to Nigeria in 2022, and claimed in her English speech: “Today, we are here to return the Benin bronzes to where they belong, to the people of Nigeria.”

Little did she (one hopes) or the German public suspect what Buhari and the NCMM would do, just three months later. Gifting the restitutions to the Oba, who is bound to no enforceable curatorial standards, is controversial in the West; not least because of the campaign by black Americans who descend from slaves, and who demand that the artworks stay safe in the museums and galleries which already display them, with their true history explained.

The Restitution Study Group protests that handing bronzes to today’s Oba rewards the Benin Kingdom twice – the first time was when slave traders bought black Americans’ manacled ancestors from the Kingdom with bracelets known as ‘manillas’ (largely brass) which were melted down to cast many of the bronzes; and now a second time today. There is nothing to stop the Oba selling his own property, and the highest known recent sale price was an off-market £10m in London for the ancient and exceptional ‘Ohly Head’ of an Oba.

A New York Post article on April 29th estimated the value of the West’s collections of bronzes at $30 billion – surely an exaggeration, but their value, assuming there were an open market, is still huge. Nigerian-cast fakes abound, so it is those pieces with a secure provenance from the 1897 Expedition which the NCMM has been most avid to extract from Western collections, including so far the Smithsonian, London’s Horniman Museum among others.

The Obas of Benin were for centuries among West Africa’s principal slave traders, selling slaves at the coast into the Atlantic trade, but also killing huge numbers in human sacrifices and propitiatory crucifixions – the sight and stench of which which appalled the 1897 Expedition as it marched into the Oba’s deserted palace. Mercifully the Expedition put a stop to these mass murders of his slaves (as the British had already stopped the Obas’ slave selling) which would otherwise have continued into the 20th century.

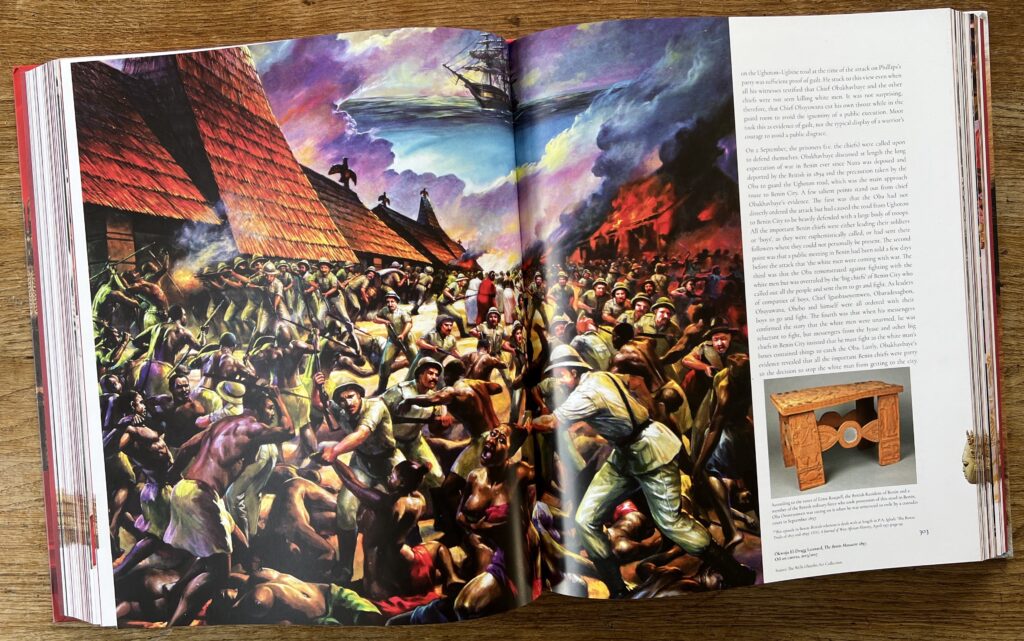

Nigerians today claim the British perpetrated a “massacre” at Benin – see the painting depicting this non-event in the Oba’s 2018 propaganda book (below) – but the reverse is the truth. It was the Oba’s chiefs who massacred an unarmed (though admittedly unwise) British expedition in January 1897; this was why the Punitive Expedition was sent the following month, and the bronzes it carried off were considered to be spoils of war.

Many of them had been standing crusted with the blood of human sacrifices on the Oba’s family altars – which, along with the Oba’s crucifixions and the history of their slave raiding and selling, is never admitted in Nigeria today. The bronze, ivory and wood relics taken from the Oba’s palace were his own personal property and not, as is claimed, cultural artefacts and heritage of the Edo people or of the Nigerian state (which didn’t then exist) or today’s NCMM.

In Cultural Property News last week the American lawyer Kate Fitz Gibbon examined the impact of President Buhari’s March decree:

By granting full ownership and control to the Oba, the decree eliminates some of the most basic expectations of national ownership – that objects will be publicly displayed and accessible for academic research and study, safely stored and conserved. Regulations governing public collections generally provide that collections management should be accountable and make provision for loans and travelling exhibitions. The Oba is not bound by any written regulations.

Abba Isa Tijani, MCMM’s director, has said multiple times that, “We see the traditional leaders as custodians of our heritage,” a statement echoed in the President’s Notice. Donor museums may not have understood that in this case, “custodian” also meant ‘owner’. The Notice will undoubtedly add significantly to the concerns of international museums about what will happen to objects returned to Nigeria. It creates huge uncertainties regarding the eventual fate of objects already sent to Nigeria and objects that may be returned to it in the future.

The Oba’s approach to ownership of some of the greatest artworks ever produced in the continent of Africa – as essentially a personal collection that exalts his slave trading ancestors and his own status – hardly meets the expectations of contemporary museums or of public policy. Especially not today, when museums are constantly being exhorted to present ‘truths’ about oppression and exploitation.

The British Museum, holding the world’s finest known collection of bronzes (the Oba’s own holdings have not been declared) has yet to comment on Buhari’s bombshell decree. Its curators were instrumental in setting up the Benin Dialogue Group (BDG) in 2007, a committee of Western curators and Nigerians which originally aimed to build a Museum in Benin, independent of government and the Oba, to house rotating loan exhibitions of Western-held bronzes for Nigerians to see at home.

Millions were given by Germany and the British Museum to fund the planning of this loan museum, not now going to be built, and Nigeria delegates grasped the opportunity presented by decolonisation mania in the West to shift the BDG’s focus from loans to outright gifts – forbidden under law to the British Museum (whose curators should clearly now resign from BDG) and requiring the Charity Commission’s permission for most U.K. museums, as these ex gratia gifts contravene the curatorial principles of their founding charters.

Scholars, Western visitors and nearly all Nigerians will find it impossible to view bronzes which the Oba claims he would make accessible in some way: the Nigerian Government officially advises against driving the 197 miles from Lagos to Benin due to the danger of carjacking and murder – people should only fly – and like much of that country, Edo State is enduring an epidemic of kidnapping.

One aspect of Buhari’s decree which seems not to have been noticed is the way it blindsided critics of the NCMM’s lackadaisical care of its own fine collections of bronzes – sadly depleted by multiple thefts by Nigerians, in Nigeria, since independence in 1960. Three pieces recently restituted by the Met Museum had found their way to New York after just such Lagos looting in recent years. Why, the NCMM can now argue, should it respond to Western critics of its neglect of all curatorial standards, when Benin bronzes henceforward all belong to the Oba? Let him go after them if he wants, it’s none of our business.

Germany is about to learn from a feature in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung the result of what their museum directors and ministers did in good faith: it will be interesting to see how that country’s people react. Just as everything seemed to be going to plan for our Pitt Rivers Museum’s curator Professor Dan Hicks, for the BDG’s convenor Professor Barbara Plankensteiner in Hamburg (“our doyenne of restitutions”, as the NCMM’s director called her), and for a cunning Nigerian plan, its own President has upset the applecart. Another surprise out of Africa.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.