Did the original lockdown of January 2020 work in China? It was the original example of how extreme restrictions could be effective in ‘controlling’ the new virus, praised and commended by the WHO in its visit the following month. Even if there was uncertainty at the time about whether Western nations could or should emulate the authoritarian state, there was no doubt among all the main players that China’s intervention had been successful and brought the virus under control. It was this apparent success that inspired governments around the world to take the plunge and follow China’s lead, beginning with Italy in February and March, and it likely lay behind the constant sense over the following years that restrictions should be working, even when they plainly were not.

So did China’s original extreme lockdown work? My colleague Dr. Noah Carl is among those who think it did. Noah accepts the well-attested evidence that lockdowns in the rest of the world largely didn’t work. But he argues that it did in Wuhan. Initially he implies the difference was due to the strictness of China’s lockdown (“To begin with, China’s lockdown was far stricter”), but his main position, stated in his conclusion, is that lockdowns with border controls when imposed early enough can stop the virus in its tracks. Thus: “When prevalence was relatively low, countries had a shot at containing Covid, so long as there were strict border controls in place.”

To defend this point of view he points to Australia and New Zealand, which seem to have kept the virus at bay until 2022 by following this method.

The main problem to my mind with the claim that China’s lockdown worked by stopping the virus in its tracks is that none of the rest of East Asia had a large wave in 2020, despite nowhere else imposing a lockdown like in Wuhan, and some places like Japan not imposing one at all. The rest of China did not have a lockdown like the one imposed in Wuhan, or initially any restrictions at all – that was supposedly part of the success, that the extreme Wuhan measures ‘contained’ the virus and protected the rest of the country, hence Italy initially imposing lockdown in a local area and then just in the north of the country.

But we now know that the idea the virus was contained in Wuhan is nonsense. The virus was not contained in Wuhan, it went all round the world and also round the country as five million people are reported to have left the city ahead of the quarantine. Whatever prevented a large outbreak occurring at that time in China and its neighbouring countries, it was not the measures imposed in Wuhan.

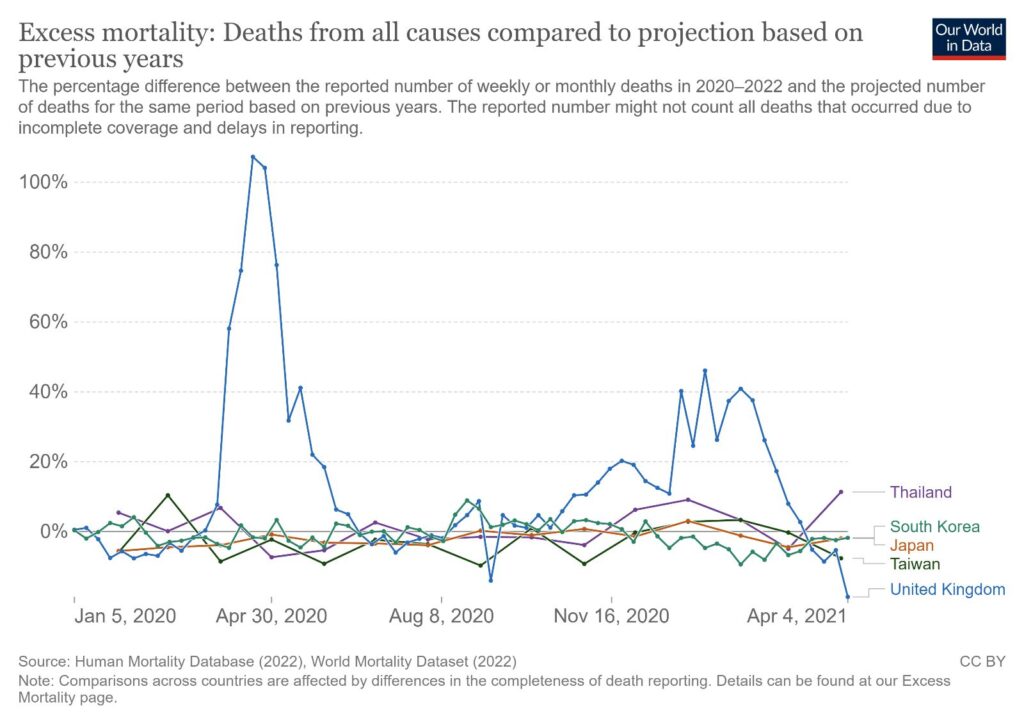

In the first wave it was frequently stated that countries had successfully controlled the virus whenever ‘cases’ went down or they had only a small outbreak. This happened with Wuhan’s lockdown, and also with South Korea’s contact tracing, which was credited with keeping the virus at bay, setting the stage for the later global obsession with test and trace, while Germany and Eastern Europe’s mild first wave was attributed to their quick, sharp lockdowns. We were all supposed to learn lessons from these countries: from China, that the harder the better; from Eastern Europe that the quicker the better; and from South Korea, that slick contact tracing was a viable alternative if you could pull it off. Of course, all these lessons were demolished as 2020 went on, as new waves of Covid kept coming irrespective of how fast, hard and often lockdown was imposed and how intensively contacts were traced. The fact that Japan didn’t do any of these things but still had low death rates in 2020 was largely ignored or put down to a peculiar Japanese X-factor. But Japan wasn’t exceptional in the region: none of the countries in East Asia had large outbreaks in the rest of 2020.

Putting this down to whatever each country did, when Japan did none of them while Western countries found none of them worked, makes no sense, and was usually based at some level on the silly idea that East Asians are just better at this kind of thing than Westerners. The more logical conclusion is that East Asia just wasn’t very susceptible to the initial strains, for whatever reason (save for the isolated outbreaks in Wuhan in January and Daegu, South Korea, in February). After all, once Delta and especially Omicron came along, these countries saw substantial waves, though their responses hadn’t changed.

As has often been noted, the first wave between January and April 2020 was an oddly patchy affair. It snowballed into large, deadly outbreaks in only a selection of locations: Wuhan, Daegu, Lombardy, Iran, north-eastern U.S., parts of Western Europe, and so on, but much of the world was spared, including areas like Eastern Europe that would later be hit hard. Numerous studies have shown that this pattern had no discernible relationship with the measures imposed. To take one example, New York implemented a strong lockdown but experienced an extraordinary number of deaths (many of which are suspected to be related to faulty treatment protocols); South Dakota, on the other hand, imposed almost no restrictions and saw no excess deaths that spring.

Some scientists have suggested this early patchiness may be due to the virus adapting to its human hosts – that it is a variant-based phenomenon, in other words. If so, this would explain why very strict border controls such as those used in New Zealand and Australia can be successful, for a time, in keeping the virus at bay, as they keep out the new variants that produce the new waves.

The question we’re looking at here, though, is not whether strict border controls can keep out the disease – I think the evidence suggests they can, for a time. It’s whether lockdown and other internal restrictions can “stop the virus in its tracks” and bring an ongoing outbreak under control. Noah suggests that lockdown can work, provided it is accompanied by strict border controls. But given the evidence that lockdowns don’t work, the question is why we should suppose that in this combination of lockdowns and strict border controls, the lockdowns are pulling any weight, rather than just being there as an unnecessary extra.

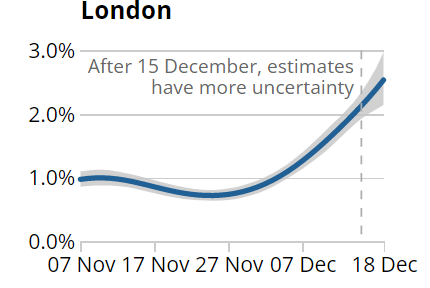

Lockdowns were all the rage in the autumn and winter of 2020-21, but the winter waves seen across the world at that time were as strong as any flu waves in recent decades, with no sign of lockdowns preventing them. Consider London, where new infections were clearly rising at the end of November despite the city being in lockdown until December 2nd and then under strict ‘Tier 2‘ restrictions.

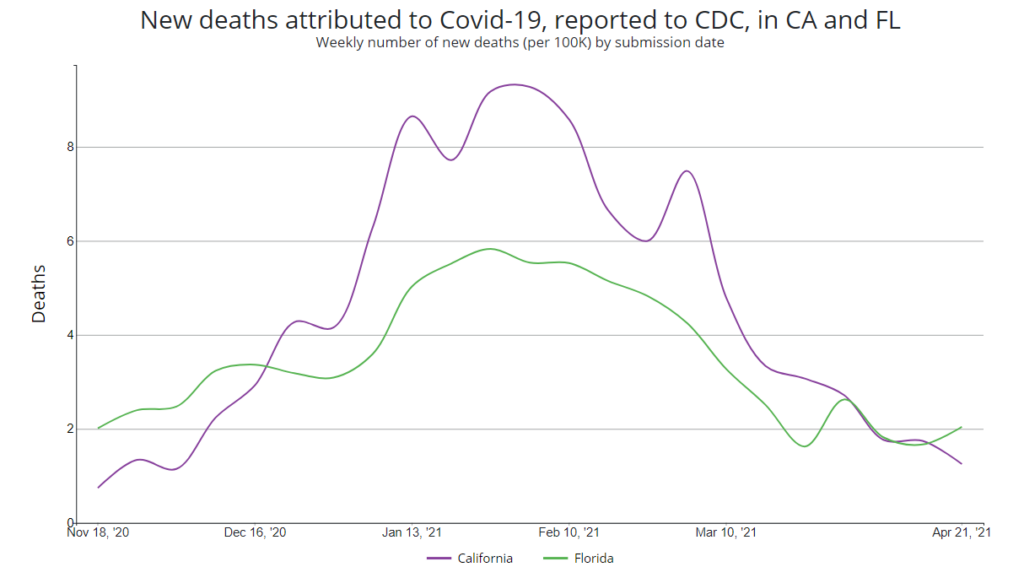

On the other hand, the few places which did not impose such strong restrictions, such as Florida, had no worse outcomes than those which did, such as California, which imposed a stay-at-home order between November 21st and December 21st, the impact of which in the chart below is not discernible.

Of course, if lockdowns, like strict border controls, did work it could only ever be a short-term solution, one that would never be justified on any sensible cost-benefit analysis. That is the argument against border controls – even if Australia and New Zealand can shut their borders tight and keep new variants (and thus new waves) out for a period of time, that doesn’t mean it’s worth it, not least because the virus will still be there when you reopen, plus the gain, such as it is, is simply not worth the pain.

The argument against lockdowns, on the other hand, is much simpler, because they do not even succeed on their own terms, as disease control. Many people struggle to accept this conclusion because it runs contrary to the ‘commonsense’ idea that keeping people apart will reduce spread. There are many reasons that lockdowns do not do this, including that large numbers of people do still go to work and share physical space, not least in hospitals, care homes, doctor’s surgeries, offices and shops, as well as in their own homes. But whatever the reason they fail, the evidence is clear that they don’t make a significant impact on outcomes – and China gives us no reason to think they do.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Much as I appreciate DS, please stop with these articles on masks and lockdowns and whether they “work” or not.

They are plain wrong on their face; no further analysis required. It was known from the start that Covid was a mild for most virus in the realms of a bad strain of flu, that was fatal almost exclusively for the frail.

We simply cannot shut the world down and stop living normally for such things.

This is just a rabbit hole.

Quite, how we can ensure this never happens again is far more pressing..

And hold the perpetrators to account!

LOL you saved me a comment. I’m bored shitless with all of this harping on about lockdowns, masks etc. It’s all been done to death, the jury was in a long time back on these matters and things have moved on significantly. Time to worry about the things coming down the pipeline in our future ( if not present ), not keep dredging up the past.

Hear, hear.

100% agree tof. I was just about to post:

Give it a bloody rest!

You said it all.

I disagree.

We need to keep trying to convince people that the world over-reacted, and that the reaction was not effective or necessary. We need to present concise, coherent arguments so that people can convince themselves that if only they had known *whatever* they would have behaved differently. Telling people they’ve been stupid is not going to be effective – they need to believe they’ve been fooled by the people they followed. It is important that people have a chance to save face as they convert from supporting the restrictions to protesting them. People need to hear the arguments or they will never convert.

Even the complicit media need to be allowed to claim ‘we were only following orders’ or some other excuse. If they aren’t allowed that fig-leaf they won’t convert until hell freezes over.

Presenting convincing arguments is key. We have to start with simple things like did lockdown work ‘here’? And go on to did they work anywhere? When did masks become a thing? Unless and until other media outlets start carrying these stories DS and the like must do so – and no matter how disheartening we have to keep offering these alternative views without alienating our audience.

Discussing whether lockdowns and masks work is a distraction and a rabbit hole. Our very own MTF is a perfect demonstration of that. Covid was never an emergency and saving lives at all costs is futile and immoral and unnatural. Those are all the arguments you need. As soon as you start arguing about what measures “worked” you more or less concede that “something” needed to be done.

The fact that Covid was never an emergency is not accepted by far too many people; we need to prove that to them somehow. Then we can move on to showing that authorities were whipping up fear to make it appear to be an emergency.

I need to have the necessary rebuttals in mind when people state that lockdown ‘worked’ in Wuhan. To counter that one I have previously relied on stating that we can’t trust China’s figures. It’s good to have additional ammunition from articles like this.

Only later will many people be ready for complex ideas like ‘don’t just do something, stand there’. Or that gathering data before deciding on anything is doing something.

Yes of course hardly anyone believes Covid was not an emergency and hardly anyone believes that saving lives at all costs is wrong and hardly anyone believes that doing nothing is often the best option. I remain convinced that these must be the starting points for any discussion of Covid and the wider subject of collectivism versus personal freedom. I think it’s really a philosophical debate about how you see life. Picking over the minutiae of whether lockdowns worked is a rabbit hole you will never come out of. If you really want a ready rebuttal then ask them to prove lockdowns worked using worldwide real world data and they will not be able to find any pattern that shows they did – another important concept which is that the burden of proof is on the lunatics imposing untried and dangerous measures.

the burden of proof

isshould be on the lunatics imposing untried and dangerous measures.But it isn’t yet for far too many.

Indeed

Sadly I don’t think Covid was some

one off aberration but an extreme manifestation of a drift that has been going on for decades

I fully agree.

So I want to get a majority on board to try to stop that drift.

Amen. We need to refute the specious utilitarian calculus entirely, root and branch, not merely say it was calculated incorrectly, if we want to prevent this from ever happening again. Lockdowns are wrong not only because they are all pain and no gain, but *a fortiori* because they are inherently a blatant violation of basic human rights and civil liberties.

And on that note, the specious notion that “rights are merely a social construct” needs to be jettisoned as well.

Talking of worrisome things coming down the pipeline, this looks slightly concerning, and worth more energy expenditure than flaming ( yawn ) lockdowns for the squillionth time. mRNA in milk! Yes, it’s ruddy China at it again;

Yes, it’s ruddy China at it again;

”From a scientific perspective, these experimental steps taken by the Chinese were a stunning success. However, given the damage mRNA vaccines have generated in terms of injuries, disabilities, and deaths, these data raise considerable ethical issues. The COVID States project has shown that 25% of Americans were successful in remaining unvaccinated. This group would have strong objections to mRNA in the food supply, particularly if it was done surreptitiously or with minimal labelling/warnings. Children could be targeted with easily administered oral vaccine dosing or potentially get mRNA through milk at school lunches and other unsupervised meals.

For those who have taken one of the COVID-19 vaccines, having milk vaccines as an EUA offering would allow even more loading of the body with synthetic mRNA which has been proven resistant to ribonucleases and may reside permanently in the human body.

These observations lead me to conclude that mRNA technology has just entered a whole new, much darker phase of development. Expect more research on and resistance to mRNA in our food supply. The Chinese have just taken the first of what will probably be many more dangerous steps for the world.”

https://petermcculloughmd.substack.com/p/chinese-load-cows-milk-with-mrna

Very disturbing news Mogs which certainly points to a dark and limited future for many.

Wow that is horrifying!

The answer is obviously no. The real issue is that that they were attempted in the first place, and the gross over reaction, and the abuse of the authority of politicians and servants etc. This includes the opportunism that has been evident in various branches of the medical trade.

The long term effect of that could well be that lots of potentially useful organisations have lost their reputation with intelligent citizens; we’ll see. What it has done is to encourage worthwhile organisations like this site!

LDs worked at; killing old people, destroying businesses, annihilating our immune systems, destroying our freedom, rendering families, increasing suicides and divorces, psychologically damaging children, handing unfettered power over to Health Nazis and effacing our constitution,.

NO. NO. NO!

Even if it were a pandemic, which it was not, they still wouldn’t work!

Indeed, they are all pain and no gain, and the therapeutic window is closed from the start.

I doubt that any DS regulars will read this article. Sorry guys… There are so many other topics to research.

Whether lockdowns ‘worked’ medically is now beside the point.

No cost benefit analysis prior to their introduction, no coherent after action review of the health, social and economic cost of their introduction now that the data is available.

Incompetent, inhuman, irresponsible, arguably criminal, definitely bovine, moronic government at home and globally, with few, notable, exceptions.

‘What did surprise us is we hadn’t really thought through the economic impacts.‘ Melinda Gates Dec 2020

Pathetic.

Amen

To repeat an old German joke I brought up in relation to this topic somewhat early: What’s that? It’s hanging on the wall and ticks and when falls down, the garden door opens? Answer: Happenstance. See also post hoc non est propter hoc and cum hoc non est propter hoc.

MTF would probably frame this as something like But if the only thing we have is handwaiving and we absolutely must do something, what other options are available?

However, this approach is wrong. Something with numerous obvious downsides whose supposed positive effects cannot be reliably assessed is something which must not be done. Not even when thousands of dimwitted hysterics demand it. These are prone to demanding anything some motormouth sold them as miracle cure for their largely imaginary problems.

Very well-said. Taiwan is another example. They had strict border controls but NO lockdowns and barely any other restrictions, and had no meaningful Covid wave until April 2022. Lockdowns are clearly an unnecessary add-on that is all pain and no gain.

You mention the five million who allegedly flew round the world (particularly to ‘Belt and Road’ terminals like Lombardy.

But you forget that, at that very time, internal travel in China was strictly banned.

And let’s not forget the Milan Mayor: – ” Go hug a Chinaman”.

I can honestly see the logic in ‘stop the spread’. But, isolation only works if its 100% controllable, which it never was. This is something airborne, and unless you can stop air circulating, it is facile and ridiculous. The fact that so many educated people appear to have been taken in by this is mind numbing. Like face screens with their large gaps at the sides. I just wanted to ask the wearers how big they thought the virus was, like the size of an apple..?

I can honestly see the logic in ‘stop the spread’.

I still think this sounds like Something must urgently be done about Marmite! If the people who kept repeating this had been serious about it, they would at least have gone to the lengths they did go to during the most-recent Ebola epidemic.

I appreciate the DS to a good part for giving us the two sides of a story. It is obviously biased towards the sceptical side, which I appreciate even more, but thereby it has laudably avoided becoming entirely an echo chamber of and for fanatics.

But I also agree with some of the criticism here, in that the really big points in such discussions are.and.must remain:

Lockdowns might or might not have worked in the meaning of delaying the spread a bit, but they have not and cannot ever ‘work’, if their multiple harms are incorporated, which proper scientists like Henderson and politicians recognized and therefore adhered to up until 2020, and, above all, there is simply zero legitimacy for state or other actors to infringe upon peoples natural rights and freedom.

Or in short: no one has the right to deem anyone or anyone’s business to be ‘essential’ or ‘not essential’.

And the very same goes for masks, test, vaccine mandates&co. and anything else related to ones sacrosanct bodily autonomy.

This is non-negotiable and non-discussable.

Straying from that line got us where we are at with regard to wokeness, free speech, the trans/women farce, man-made climate change/CO2 hoax etc..

“Do Lockdowns Work?”

No!

Good article, until I got to this sentence: “The question we’re looking at here, though, is not whether strict border controls can keep out the disease – I think the evidence suggests they can, for a time.”

Come on. The UK is supposed to have had this big covid wave in early 2020 – but we know now from FOI requests that only around 1000 people died OF covid in 2020 so the whole idea that there was a big covid wave is nonsense.

As Will rightly mentions covid was spreading all around the world before Wuhan locked down. I remember in 2020 watching reported death rates all around the world going up and up but China’s staying at a few hundred. Who can believe China’s own figures?

As for New Zealand, did they REALLY keep the virus out as they claimed to have? Loads of people were sick in NZ in March 2020 with some kind of bug as we were here at around the time we all went into lockdown. And then after that did nobody in New Zealand get a respiratory infection in all that time their borders were closed? I very much doubt it. And there were reports that they banned the immunity tests so that people wouldn’t realise they had already had it and were immune.Planes were still arriving, ships were still coming and going all that time. Even Antartica couldn’t keep covid out. It is just far too much of a stretch to believe that New Zealand actually kept covid out as it claimed to have.

And then there is the question if “covid” even exists at all or are the covid tests just picking up cold/flu bugs?