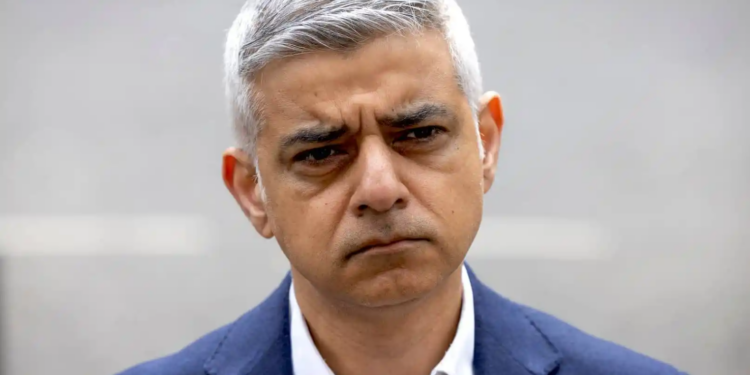

The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, claims that his aggressive anti-car policies will help Londoners breathe and stop them dying. According to his and his officers’ many statements, 4,000 deaths are caused by air pollution in our capital city each year. “I’m not prepared to have the early death or life-limiting illness of another Londoner on my conscience,” he tweets, explaining his crusade.

This is surely an urgent public health emergency – a crisis, as he puts it. “How many more children are we willing to let inhale poison?” But beyond the emotional urgency, what does the science actually say? Is our favoured form of mobility really ‘poisoning’ us?

Claims like Khan’s have always bothered me because I grew up hearing my grandparents’ stories about London’s smog, which is now gone. Its air is cleaner than perhaps at any time in the City’s history – just 2% of the levels of particulate matter are recorded today, compared with its peak in the 1890s. We no longer burn coal to heat our homes or power what remains of our industries – not in the capital at least. Technologies have given us much cleaner-burning engines, and vehicle emissions regulations have required a constant level of improvement from manufacturers.

Much may be at stake. The era of the rise of the motor car is the era of the most radical improvements in environmental and human health and wealth. Is it a coincidence? The majority of households in the country now enjoy – take for granted – a level of independence and mobility that was inconceivable to earlier generations. What if it is not a coincidence? Might Khan’s misplaced urgency be causing us to lose something that has been fundamental to our economic development and consequently our longer, healthier lives?

If it means anything to be a sceptic, it means not taking seemingly unimpeachable injunctions at face value. It means taking apart statements, such as Khan’s and those of countless local authorities that people are killed by air pollution, and that restrictions on the use of private transport such as ULEZ (ultra-low emission zone) and 15-minute cities will improve public health. And it means not being dazzled by either the authority of institutional science or cowed by cheap and shrill moral arguments. Accordingly, Climate Debate U.K. and the Together Declaration (both of which I am involved with) have jointly produced a report on the science behind Khan’s claims.

Khan’s ‘4,000 deaths’ figure comes from an analysis produced by the Environmental Research Group (ERG) at Imperial College London. The researchers indeed found in a report, commissioned by Transport for London and the Greater London Authority, which are both offices of the Mayor, that “the equivalent of between 3,600 to 4,100 deaths (61,800 to 70,200 life years lost) were estimated to be attributable to human-made PM2.5 and NO2“. But notice that this statement is already quite different to Khan’s claims of ‘4,000 deaths’, which are, in the report’s view, equivalent to between 61,800 and 70,200 “life years lost”.

In everyday usage, the word ‘death’ has no ‘equivalent’. A death is a death. A death often marks the most painful chapters of a family’s story, and the final moment of an individual’s life. But in mortality risk statistical analyses, a ‘death’ is an interchangeable term – ‘equivalent to’ so many life years. And so, given this interchangeability of like terms, the loss of 70,200 life years is equivalent to the loss of 69 hours of life per year, for each of the 8.9 million Londoners. Over the course of an 85-year life, that amounts to around 244 days – the 85 year-old may have reached 86, perhaps, had there been no air pollution. We will return to that question…

The ERG’s analysis was not new science. It was based on methodology produced in 2018 by the U.K. Government’s Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants (COMEAP). COMEAP reviewed the existing science to try to produce an estimate of mortality risk associated with air pollution from all causes. And it is an extremely interesting read on the state of science’s understanding. COMEAP were given the task of producing a consensus but failed. Much of the 152-page report is given over to a discussion between the views of majority and minority factions within the committee. From the opening paragraphs, COMEAP’s report categorically states that a debate exists within the science and within the committee itself. I cannot recall ever having read a scientific report which is so far from unequivocal about its findings, and which gave voice to fundamental disagreements.

At the centre of the debate is the issue of causality. Whereas air pollution seems to be somewhat correlated with an increased mortality risk, many socioeconomic factors confound an objective interpretation of this link. The minority of the committee found it too problematic, arguing that, “basing mortality burden calculations on long-term average ambient concentrations of NO2 will, despite listing caveats, mislead the public into believing that exposure to long-term average ambient concentrations of NO2 is causally associated with an increased risk of death”. The majority only partially disagreed, and argued that mortality risk estimates could be useful, “provided that the caveats and uncertainties are communicated clearly”. The disagreement caused a number of the minority to state their disassociation from the report, which went on to produce estimates of mortality risk.

Where is Khan’s clear communication of the “caveats and uncertainties” that ‘the Science’ requires? Khan, and many other advocates of policy that will impose radical changes on society have omitted what ‘the Science’ insists on. And in doing so, have they not, exactly as the COMEAP minority argued, “misled the public”? In our report, in which we ‘follow the Science’, we argue that they have, because there is a very substantial difference between what COMEAP’s method calls a ‘death’ (an interchangeable statistic) and what people understand by the word ‘death’ (the actual end of a person’s life).

To mitigate their embarrassment, the false use of the term ‘death’ is now being explained by pro-ULEZ, anti-car reports as a “statistical construct”. But there remains the problem that 4,000 ‘statistical constructs’ have been used to advance a policy agenda, to ‘scare the pants off’ people – a political tactic that sceptics are both familiar with and resent the use of for precisely that reason: politicians, officials, journalists and campaigners seek not to engage rational minds, but emotions. It is in most people’s disposition to believe in the good faith of scientists and institutional science, but here these seemingly impartial, objective, rational bodies are commissioned by the Mayor to support his playing fast-and-loose with ‘statistical constructs’ – language games – when they ought to be challenging him.

Among the authors of the ERG report are three air pollution researchers, David Dajnak, Sean Beevers, and Heather Walton, whose academic profiles each proudly state their having “worked closely with London policy makers”, on developing ULEZ and other policies. So much for the ERG’s claimed ‘independence’. Whether or not their work is flawed, there is arguably too little distance between this form of academia and politics to allow it to be taken at face value. Not even academics should be free to mark their own homework.

The problem gets worse when we consider City Hall’s self-evaluation of the recent ULEZ expansion, which we also cover in our report. In their estimation, the Mayor’s policies have been an unparalleled success, leading to “four million people breathing cleaner air”, and “46% lower” NO2 concentrations in Central London “than they would have been in inner London without the ULEZ”. But as we explain, there are insufficient data to make such a claim. For the pre-ULEZ era, just three roadside air-pollution monitors were operational, two of which were adjacent to or at the entrance to tunnels, while the other was situated between a busy bus stop and a traffic-light controlled traffic junction. These sparse data cannot possibly have produced a representative sample of Central London’s air, and this problem was compounded by the installation of new monitoring stations placed on much quieter, more residential streets in the post-ULEZ era. Like is not compared with like.

Despite such obvious flaws in the data and method of evaluation, City Hall proclaimed that it “underwent independent peer review” and survived. And the peer-reviewer? He just happened to be another Imperial College air pollution academic, Dr. Gary Fuller. Here is his Twitter profile:

Do we detect a hint of activism about Dr. Gary’s research interests? Might it be a bit of a stretch calling it ‘peer-review’, which is typically an anonymous process involving more than just one activist academic in evaluating the claims made in a work? I will leave readers, who are no doubt familiar with other public health work produced by Imperial College’s academics, to judge for themselves whether or not City Hall got the ‘peer-review’ they were expecting from the impartial, objective, rational and not-at-all-pushing-his-scary-book researcher.

But what of those 244 days that the would-be 86 year-old did not get to enjoy? If we could extend life, on average, by this amount, surely it is right to consider policies that may deliver such a benefit?

In risk analysis, as with politics, comparison and context are everything. Since the middle of the last century, life expectancy in the U.K. has been increasing (until Covid and lockdowns – thanks, Imperial) at a rate of 73 days per year. This, it turns out, is driven much more by wealth – income – than by environmental factors, such as air pollution. Half of the differences in life expectancy at the London borough level can be explained by differences in household income. And this relationship is far stronger than the putative relationship between air pollution exposure and life expectancy. According to data from the Health Foundation, just small increases in post-housing cost income produces remarkable benefits in terms of Healthy Life Expectancy (HLE), especially for those on lower incomes. An increase of just £412 per year was associated with 219 days increased Healthy Life Expectancy.

This very strong correlation between wealth and health completely debunks the green preoccupation with the environment. It turns out that it is Londoners’ most wealthy boroughs that are most exposed to air pollution, but which enjoy the greatest longevity. And so, given the interchangeability of ‘statistical constructs’, we can point out by ‘following the science’ that the same health benefit as eliminating air pollution can be achieved by increasing incomes by £459 per year.

But can’t we do both – have clean air and economic growth to drive improved health and life expectancy? Not by the methods championed by the likes of Khan. Restraint is the environmentalists’ preferred policy intervention. On the green view, there is no problem that cannot be fixed by banning, taxing and fining. Hence, shops and trades that have managed to survive lockdowns, only to have low traffic neighbourhoods (LTN) dumped on them are reporting loss of custom and increased costs.

Roads are the routes by which money is moved around society, from customer to shop, from shop to supplier, from supplier to manufacturer, and so on. Our economy is dependent, not just on the mobility of the cash itself, but those who exchange it for goods and services. A draconian restriction on the use of roads, as fantasised by every earnest road-blocking climate activist and every green blob wonk, means a significant reduction in wealth. And as we have seen, a reduction in wealth is ‘equivalent to’ a reduction in health and longevity.

The Mayor’s office has claimed that our report is an attempt to “mislead the public by seeking to call into question the scientific evidence”. Nothing could be further from the truth. We have shown that it is the Mayor who has departed from COMEAP’s science. He has used emotive language which COMEAP says is not justified. He has abandoned the “caveats and uncertainties” COMEAP requires for political expediency. And we have used COMEAP’s method – using equivalent terms to compare degrees of risk – to demonstrate that Khan’s ideological policy agenda is more toxic and harmful to human health than air pollution.

What COMEAP found, and what the ‘statistical construct’ of ‘death’ demonstrates, is not people being killed by toxic substances, but that, at worst, air pollution slightly impedes the rate at which life expectancy increases. If we could eliminate air pollution, we could perhaps increase the rate of 73 days per year by one or two days. But this doesn’t take any account of the loss of life expectancy from the considerable economic impact of reducing human mobility. We might have hoped academics would undertake a serious, objective and policy-neutral cost-benefit analysis along these lines. But given the dominance of green ideology at universities across the country, and the manifestly policy-oriented nature of academics’ research agendas, such hopes are far-fetched. It falls on sceptics and engaged members of the public to make the facts known to politicians and researchers.

Read the new report from Climate Debate U.K. and the Together Declaration here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Don’t anybody tell him that oxygen starts poisoning us from the moment we take our first breath…

Yes I seem to remember watching something on telly about oxygen actually causing death something to do with the rate of metabolism? Obviously everything nowadays has to be taken with a pinch of salt but interesting.

Instead of guessing how many die, just show us the death certificates of the 4000 as proof of death by air pollution! I’m sure if they existed they would be well promoted!

The tragic case of the young girl is,as yet, the first and only!.

So, how many have this as official cause of death?

……1!

Has Imperial College calculated how many life years have been lost due to the stabbings in London which Mayor Khan has done nothing to stop?

I rather suspect that tackling violent crime would save considerably more life years than Khan’s war on the motorist.

I think the aim is to only facilitate the stabbings if the perpetrator uses a non polluting vehicle.

I rather suspect that tackling violent crime would save considerably more life years than Khan’s war on the motorist.

I think it is unlikely. Here are the total homicide figures for London over the last five years (I couldn’t find how many of those were knife crimes).

Apr 2017 to Mar 2018 155

Apr 2018 to Mar 2019 123

Apr 2019 to Mar 2020 145

Apr 2020 to Mar 2021 125

Apr 2021 to Mar 2022 126

It’s about power, money and control and nothing to do with pollution. Thanks again Imperial, where would we be without your “experts” (much better off).

In the tragic case of this young girl I note that toxic air pollution was “listed” on the death certificate. I deduce then that it was one of several contributory factors.

Without knowing the contents of the list and the relative effects of each factor then Khan’s conclusion might be as misleading as “dying with Covid”.

When I was a doctor, what I listed on death certificates was based on my professional opinion, not on pathological proof. If I was trained to believe that air-pollution frequently caused death by respiratory disease, I’m sure I’d have included it quite often in urban asthmatic deaths.

Dear Ben,

Thanks for a great clear and informative article.

Julian

Hear hear!

I share the scepticism about Khan’s figures. But why not apply the same scepticism to bold statements such as:

A draconian restriction on the use of roads, as fantasised by every earnest road-blocking climate activist and every green blob wonk, means a significant reduction in wealth.

An increase of just £412 per year was associated with 219 days increased Healthy Life Expectancy.

In particular “associated with” does not mean “caused by”.

I think it’s generally self-evident that road transport and prosperity go together. But I don’t much care, I just want to be able to drive places as it makes my life more fun, which is the point of life.

Which is why Ben used the expression “associated with”, but I think we all understand that life often involves trade-offs between “good” and “bad” things which is why I have a significant number of bottles of scotch on my shelf that are capable of causing or being associated with either enjoyment or pain.

Hear hear although in my case it’s gin amongst other things.

I agree with you – daft that you get this negative reaction. The phrase, “Half of the differences in life expectancy at the London borough level can be explained by differences in household income.” struck me as unscientific and misleading as Khan’s proposition.

4,000 deaths p.a. as modelled by Imperial. Google the figure and it’s 9,400pa.

Actual ONS evidenced based deaths provably attributable to poor air quality between 2001 and 2021: One death.

Check out ‘The Conservative Woman’. article 24Mar 2023. ‘The Bogus Figures Behind Mayor Khan’s Emissions Drive.’

https://www.conservativewoman.co.uk/the-bogus-figures-behind-mayor-khans-emissions-drive/

Excellent article thanks for the link.

The whole death-by-particulates thing (and I would assume NO2 as well) seems to have its origin in the “linear response, zero threshold” assumption about toxicity, which arose from the work on mutagenic radiation by Hermann Muller back in the 1930s. Even as he went to claim his Nobel Prize, members of his own team had disproved the theory, but it became an unexamined scientific axiom anyway, and is now generalised from radiation to everything. The error explains, incidentally, why millions of civilian deaths are predicted from a Chernobyl-type accident, but the only actual bodies that turn up are those who die from the disruption of the evacuation.

Hence, connect a diesel exhaust to a rat’s cage, and if 90% die at a certain percentage of PM.2.5, a quick calculation will tell you that at miniscule concentrations 4,000 people a year will die in London, and you never have to prove a single particulate-related death for the model to be considered valid. William Briggs has an excellent chapter on it in his book Uncertainty.

The fallacy is proven by considering water, which induces toxicity and sometimes death from hyponatremia if you drink, say, 4 litres within an hour or two. So if, for example, 5 litres in 2 hours kills 50% of people, the zero-threshold assumption would build a model predicting that 5ml in 2 hours would kill 1 in 2000 people. It’s clearly nonsense, because all toxins in practice have a safe threshold, and toxicologists have estimated that the dose of PM2.5 is so low over an urban lifetime that it would have to be the most toxic substance on earth to kill anyone.

As in so many cases, only about one independently minded scientist has questioned the global zero-threshold assumption and demonstrated its shaky foundations, but since it underpins so many branches of Kuhnian “normal science,” the outcomes of scientific conferences are a foregone conclusion even before politicians get involved.

In the international development world a lot of people behind desks in high income countries were generously throwing other people’s money at “clean cookstoves” programmes on the assumption that people cooking on open fires were being killed by indoor particulates. When somebody actually bothered to look whether the avalanche of money was helping they found no effect on respiratory disease, although they did find a large reduction in childhood burns. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/10/161026081142.htm

That’s interesting, because many in the anti-net-zero lobby have taken the reality of deaths from open fires for granted. My thoughts above led to my having some doubts, given that open fires in houses have been the universal human experience since the early palaeolithic.

I don’t doubt that average life-span was shorter before the modern age, but the folks not killed by raiders often lived to old age by the fire!

Isn’t it odd that the people who worry about overpopulation are often also the same ones that want to impose some scheme or other on all of us to “save lives”?

Almost as if they were worried about neither.

The Far left politics Behind Sadiq Khan’s ULEZ Anti-Car Crusade.

I remember when every body in Chairman Mao China used to ride bicycle because they weren’t allowed to own car.

The pattern is first you copy the Chinese lockdown then you turn the Western World into Communist China,

***********************************************Wednesday 29th March 11am to 12pm

Yellow Freedom Boards

Junction Eversley Road &

Langley Common Road, Arborfield,

Wokingham RG2 9PS

I was brought up in a northern industrial city in the 1960’s. There were many days in the winter especially where you couldn’t see the hills around for smog, and the smell of sulphur was just considered normal. Sadly, also considered normal were the frequently early deaths from bronchitis, but then it was all cold houses and coal fires too. If Mayor Khan thinks we have a problem with toxins in the air, I invite him to join me in my time machine, where we can go back and find out why the first ‘Clean Air Act’ was passed in 1956. Then he can tell us why we need something at below a 10th of that level to survive.

I can appreciate that it is very sad to lose a child, especially in tragic circumstances, but whenever I hear about Susan’s Law, or Billy’s Law, I recoil at the very thought. Usually emotion led, and poorly thought about on the basis that ‘if it saves one life its worth it’. Well, I have to disagree. Laws should be introduced only where necessary.

Take ‘Natasha’s Law’, so called after a tragic young girl who ate some food that was incorrectly labelled and died as a result. So, now food producers big and small have to have allergy information, kept up to date, and printed on labels at huge expense in time to monitor and maintain this information for every small food business, restaurant and cafe. It is a vast overhead for a sector already hard pushed. So how many deaths were there/are there from Anaphylaxis Shock in the UK each year that we are preventing. A study by Imperial (yes, I know…) in 2021 said that deaths have declined significantly in the last 20 years and are now fewer than 10 in the UK each year.

Thank you for this analysis Ben, it’s a shame that the other side of this argument doesn’t use people of such high ability to dissect their own arguments. But of course when your salary depends on toeing the line of your employer it tends to corrupt the mechanisms.

I had a 10km (~ 6.2miles) walk through London last Friday, from Paddington Station to Camden Town tube station just around rush hour time, back again shortly after 10pm. I did this mostly to escape the crowding, noise and terribly bad air on the tube when it’s busy which frequently makes me feel as if I was about to run out of oxygen despite breathing until I have managed to escape from these vaults of horror again. Khan is crazy if he believes there’s a significant air pollution problem in London and should perhaps investigate the health of effects of stress, noise and lack of fresh air on the tube.

“I’m not prepared to have the early death or life-limiting illness of another Londoner on my conscience,” he tweets, explaining his crusade.”

Says Suddenly Khant.

Obviously his complete refusal to speak up for London’s children throughout the Jabathon is an entirely different matter and he is quite happy to carry those childrens deaths on his conscience. He’s a firkin martyr.

What conscience? He’s a politician so his conscience was surgically excised at birth.

Have to remember you’re dealing with someone who is utterly impervious to straightforward facts. He’s been asked repeatedly if a sharp increase under his mayorship in for instance the number of fatal stabbings in London suggests anything negative about his policies, and he simply says no. You could stab someone to death in front of him and he’s say it’s not happening. You’re dealing with the quintessence of unintelligent, uncaring, self-deluding leftist idealism. Good luck.

Sadiq Khan distorting facts to make a political point? Surely not

But Khan is quite happy to let young people lose their lives through “stabbings ” typical Islamic hypocrite

Gary Fuller; Imperial college and contributor to the Guardian. What could go wrong!

i can’t see the benefit as we’d probably end up spending an additional 244 days queuing for or on the bus…