Last month the U.S. CDC and FDA released a joint statement stating that they had identified a statistical signal of increased strokes after vaccination with Pfizer’s bivalent Covid booster vaccine in those aged 65 and over. This sounds worrying, but the FDA and CDC were quick to reassure the population that they were only being open and transparent in releasing this information, and that they were sure that in reality the vaccines were very very safe and highly effective (and so everyone older than six months of age should get their dose whenever they’re told to by their benevolent Government).

However, I was a bit puzzled by their joint statement – while it was eager with its reassurances, it didn’t actually include any data to support this reassurance. All we were told is that in the three weeks after vaccination there was a higher risk of stroke compared with the four to six week period after vaccination in those aged 65 or older. But there was no quantitative data on this relative risk, no information at all on the risk after this six week period and no statement on whether they’d actually even investigated stroke risk in other age groups.

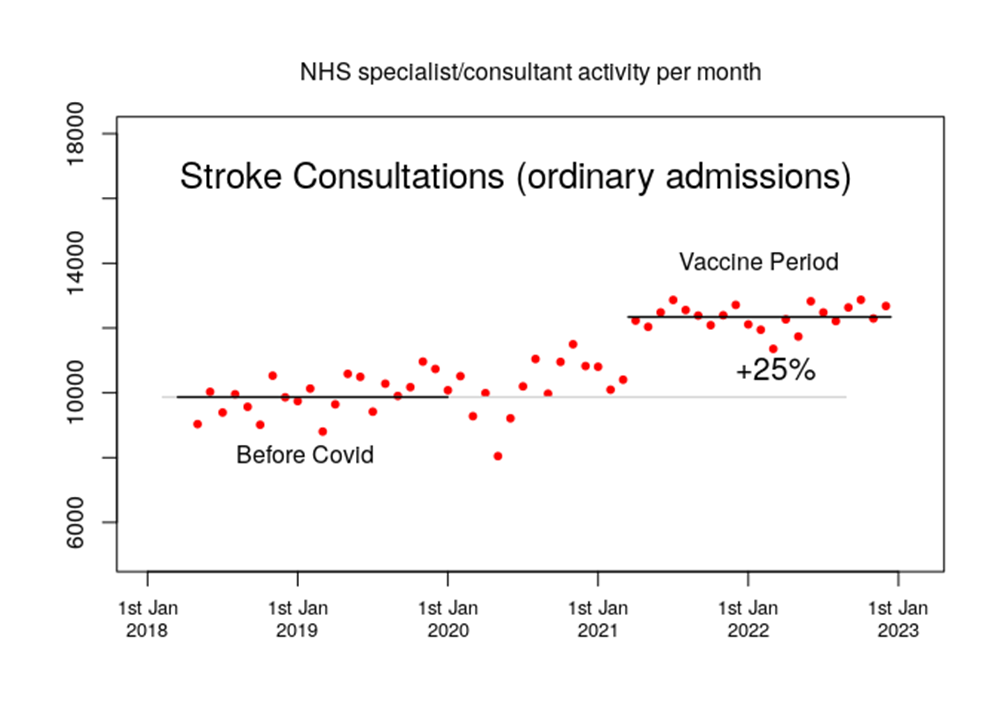

Given this lack of data I thought I’d head over to the data on NHS hospital consultant activity to see whether that would offer some insight into the incidence of stroke in the U.K. over the last few years.

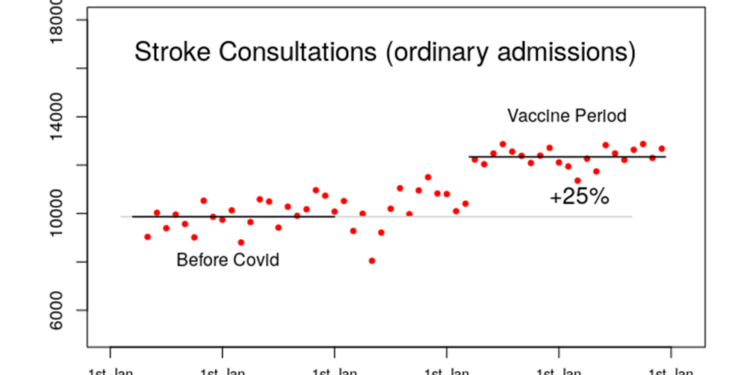

Hmm. The workload of stroke specialists appears to have suddenly increased in the U.K. by a very large factor just at the point where the vaccines were being rolled out in large numbers. As I recall the Government was very pleased with the speed at which it managed to vaccinate such large numbers of people over such a short period of time, so if there were a significant increased risk of stroke then an extremely rapid rise in stroke incidence would be exactly what you’d expect. Of course, this might just be coincidence, despite this strong temporal association with the vaccines…

In many respects this type of statistical signal is the same as the increase in excess deaths that we’ve seen in the U.K. and many other countries since the vaccines were rolled out – there is that temporal association with the vaccines but there’s little actual scientific evidence that it is due to the vaccines (although that lack of evidence might just be due to a strange reluctance on the part of our authorities to investigate this phenomenon). Various alternative explanations have been rolled out for the excess deaths such as their being due to lockdowns (including lack of NHS care) or due to Covid itself (or eggs, climate change, stress about Ukraine etc.). Strangely though, the one thing that is never said is that it would be fairly easy to exclude the vaccines as being the cause of the excess deaths – simply undertake a retrospective matched cohort study into the number of excess deaths by vaccination status. Given the extraordinarily high excess deaths we’ve been seeing, the lack of such a study is weird.

And the same applies to this statistical signal in increased strokes in the U.K. in the period since the Covid vaccinations started to be given. Surely our Government would love to identify all and any increased risks that our population is under – surely?

I note in particular that there appears to be a somewhat higher rate of consultant activity in the second half of 2020 – perhaps the higher incidence rates aren’t anything to do with the vaccines after all? On the other hand, it might simply be that during autumn 2020, when the NHS started to dial down its hysterical Covid response, the specialists in stroke medicine were starting to treat cases where the initial stroke had occurred during the NHS shutdown earlier in the year. This could explain the higher consultation rates in the second half of 2020. However, it won’t be the case that this same mechanism would persist over longer timescale – strokes aren’t like some other conditions where consultants might see individuals at higher risk or where there is a long waiting list to get treatment. Rather, people typically see a consultant specialising in strokes at their bedside immediately after a stroke and typically the sooner they’re seen the better. There certainly won’t be many people, if any, waiting a over a year for their consultation.

The other interesting aspect of the increase in the NHS consultant activity data is that the increased activity doesn’t seem to be reducing. I note that the CDC/FDA announcement on strokes only found an increased risk in the three weeks after vaccination compared with the following three weeks, so maybe these persistently high stroke incidence data indicate that it isn’t associated with the vaccines. Or, alternatively, the vaccines might induce a sustained increased risk, in which case we would be seeing a new normal of increased stroke risk after vaccination. If this were the case the CDC and FDA should change their methods to look at risks far beyond their six week post vaccination period. Indeed, it is a bit odd that they limit their time period in this way. Didn’t they want to find any evidence of longer term increased stroke risk? Surely the population of the USA would be very keen to have this information. One other note on the consistently high stroke activity in NHS hospitals is that we don’t know how close to capacity they are. Is the seemingly consistently high activity simply reflecting this speciality working at 100%, with some spikes in the data by for each Covid wave or vaccination drive being masked by the inability of the speciality to respond appropriately?

The NHS hospital episodes data appear to have offered an early indication that there might be a problem – after all, even in spring 2021 the number of strokes appears to have been substantially higher than in the pre-Covid period. Can we use other NHS data to explore this risk further? In this and subsequent posts I’ll also be making use of three other datasets that the NHS issues on how drugs are being used in the U.K.:

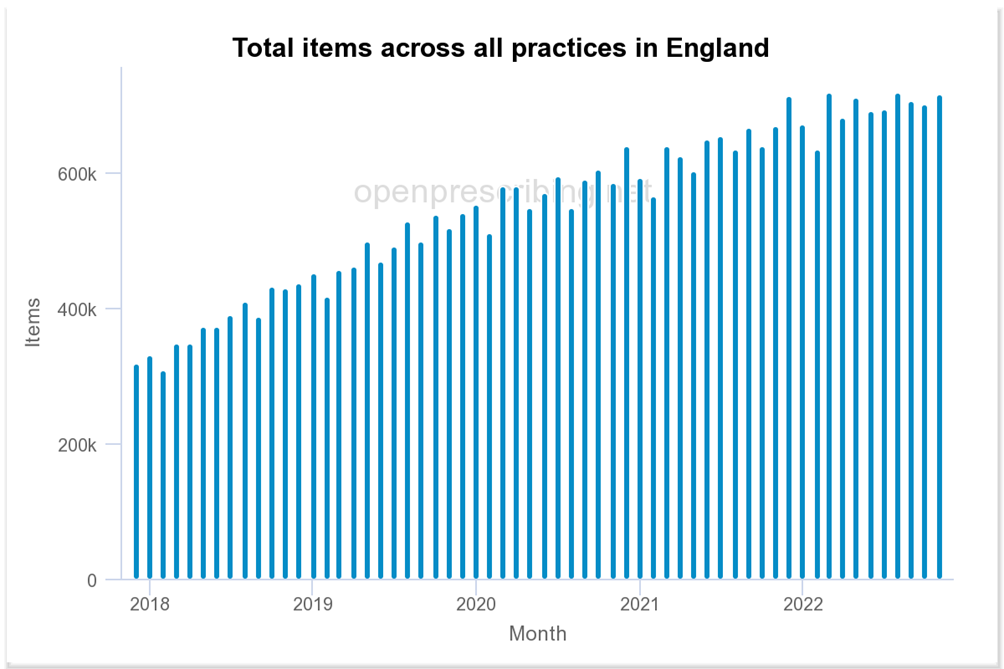

- Prescriptions written by GPs are collated in the Practice Level Prescribing Data Series – this data series is difficult to use, but fortunately an independent body, Openprescribing, has made these data available in a more user-friendly format. Note that all the datasets have been complicated by Covid – for the GP dataset it is mainly that GP services were significantly curtailed in 2020 and they remain somewhat less accessible compared with the pre-Covid period.

- The issuance of drugs by hospitals is available in the Secondary Care Medicines Dataset. Note that the NHS doesn’t make this an easy dataset to use – it is almost as if it is required to publish the data, but doesn’t really want anyone actually using it. The hospitals prescription dataset is complicated by the fact that hospitals nearly closed down to non-Covid patients in early 2020, and nearly all medicines show a significant decline in hospital use over this period, with many taking some time to recover to the pre-2020 trend.

- Regular hospital prescriptions can only be dispensed in a hospital pharmacy, so there is a separate database for prescriptions written in a hospital setting but intended to be dispensed by a normal pharmacist. Again, this dataset isn’t particularly easy to work with. In my posts on this topic I’ll often describe these particular data as ‘emergency prescriptions’ but note that this category of prescription is broader than merely those prescriptions issued in accident and emergency departments for dispensing in a regular pharmacy. The problem with the data for hospital prescriptions written for dispensing in the community is that over the Covid period people had little choice but to attend A&E for minor problems because it had become relatively difficult to see a GP.

The obvious first drug to investigate is alteplase, a clot-busting drug used in the hours after a stroke to get rid of the clots that are causing the problem. However, there is no strong statistical signal for alteplase – unfortunately, this drug has been in short supply for some time due to unusually high global demand. Strangely, the other emergency clot-busting drug, tenecteplase, is also in short supply for the same reason. There appears to be no explanation given for this global increase in demand.

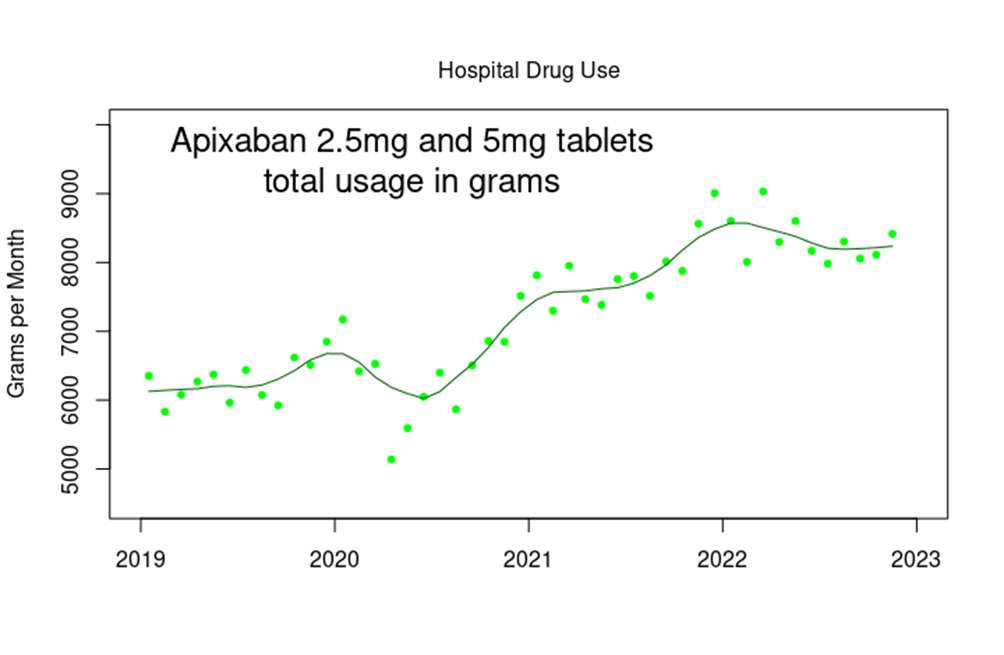

In normal times, without global shortages, clot-busting drugs are only used for a minority of stroke patients – not only do they need to be used very soon after the stroke occurred, but also they can make things much worse if applied in the wrong types of stroke and it takes time to gather this evidence. On average only about 10% of strokes are treated using these drugs. For most strokes that involve clots the clot-busters can’t be used and thus rapid-acting anti-coagulants become the drug of choice, used in high doses under close medical supervision in a hospital setting. The hospital drug use data do show an increased use of these anti-clotting drugs, such as apixaban.

What’s particularly interesting in the graph above is the short spike in issuance of apixaban around the turn of 2019-2020 – is this a sign of Covid itself being clot-promoting, with something since the start of 2021 increasing this problem? Also, note the timing of that early peak, at the turn of 2019-2020 – do these data support the theory that Covid was endemic in the U.K. in late 2019, with the increased cases of ‘respiratory disease’ being blamed on an unusually early outbreak of influenza?

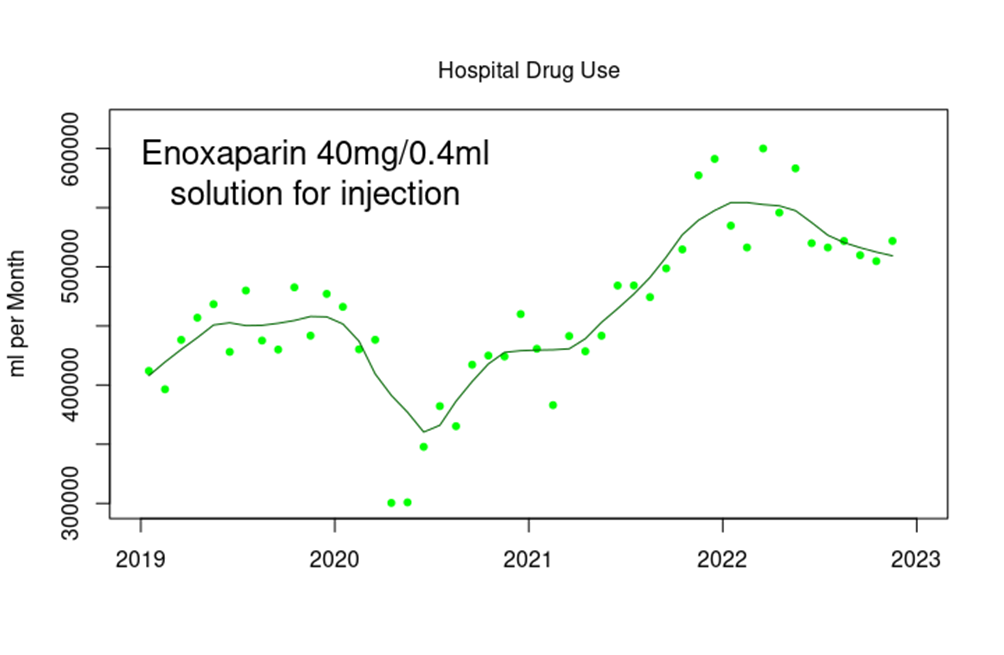

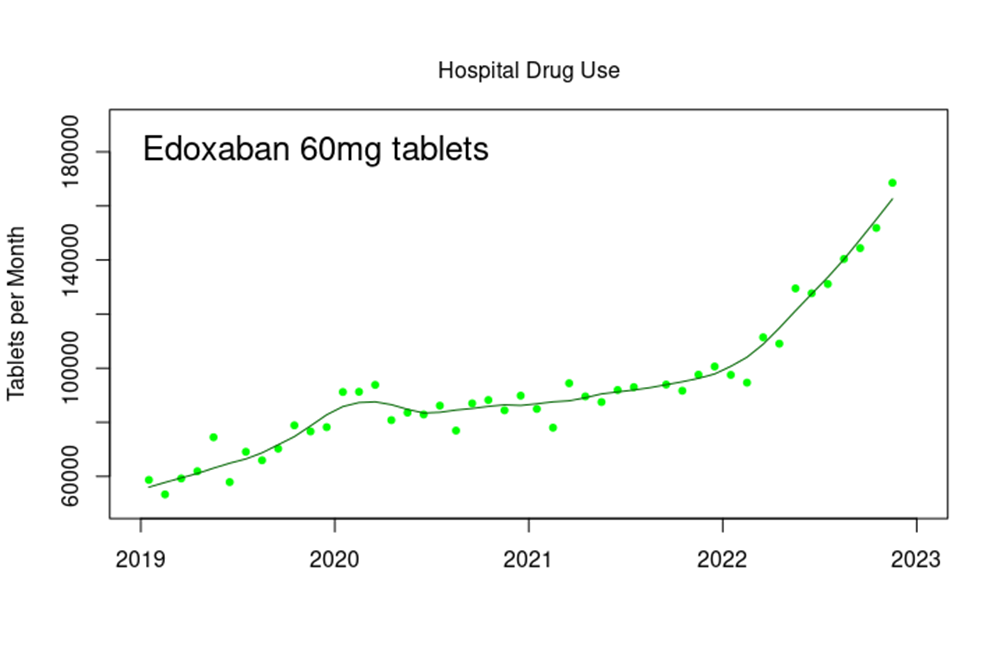

There has been a similar increase in the use of other anticoagulants, such as enoxaparin and edoxaban in a hospital setting.

The data for prescriptions of general ‘blood-thinning’ drugs are a bit difficult to interpret, however, given the general increase in the use of these drugs in the community. The graph below shows the increase in prescriptions written for apixaban by GPs over the last few years.

It is clearly difficult to untangle changes in risk given this years-long general trend as more and more in our population are introduced to the benefits of the pharmaceutical industry. One thing is fairly clear, however – there doesn’t seem to have been any noticeable decline in the issuance of these (and other) cardiovascular drugs during the Covid lockdowns, despite claims by our authorities that this has been the driving force of the increase in excess deaths seen during 2022.

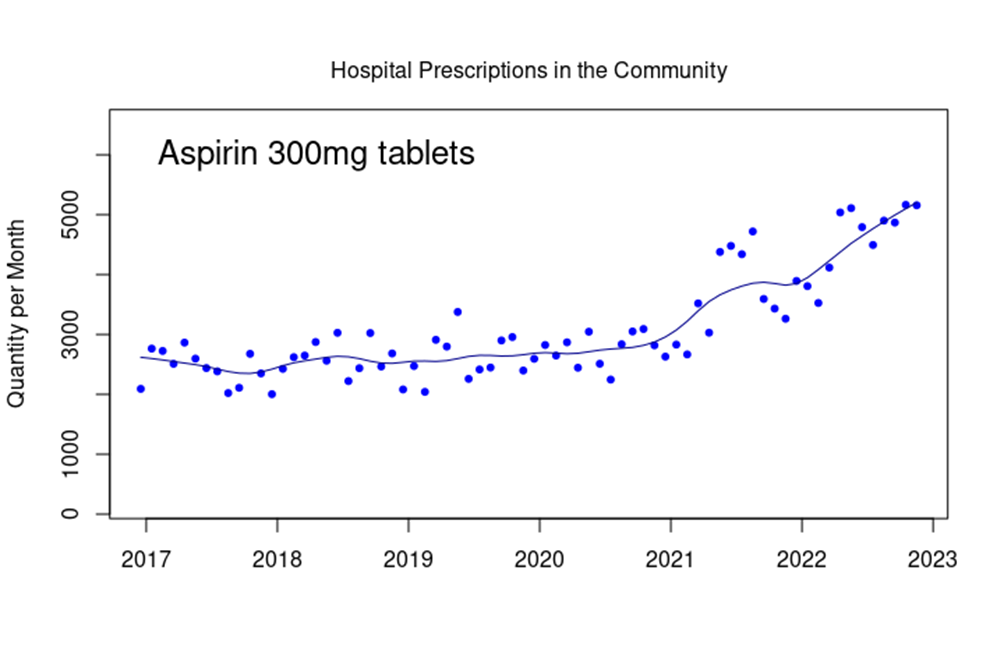

There is also a strange upwards trend in the prescription of aspirin (300mg) in hospitals for dispensing within normal pharmacies.

Note how the number of tablets dispensed increases markedly from the start of 2021 and how there appears to be a maintained upwards trend. It is important to note that while aspirin is often taken as a mild painkiller, this is generally not the preferred use within a modern medical context. It is likely that these prescriptions will relate to aspirin’s anti-coagulant properties.

An important aspect of the data that I’ve shown here is that they don’t give any indication as to the characteristics of the individuals behind this increase in consultations for stroke. While it is reasonable to assume that this increased risk would be proportionate to the prior risk, this is by no means certain. For example, if the risk of stroke increased to one in 200 per five years for everyone in the population, this increase would be significant for younger individuals, but wouldn’t impact much on stroke risk for those aged 85 years or older. This lack of data on changes in stroke risk by age certainly isn’t helping us understand the changes in risk that our population appears to be experiencing. Still, I very much hope that the increased stroke risk isn’t being seen in younger adults.

The data suggest that something is going on with blood clotting within the population of the U.K., resulting in an increase in strokes and presumably other conditions such as deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Although the U.S. FDA and CDC claim (without offering supporting data) that there isn’t really a net increase in strokes associated with the vaccines, the data available from the NHS suggest that there might well be a non-trivial increased risk. Our population deserve a comprehensive study into the risks associated with blood clotting in this post-Covid and post-vaccine age.

I suppose I could stop here – there appears to be an indication of an increased stroke risk in the U.K. population over the past few years, and it is surely time for our Government to look much more seriously into this unhappy change in the health of the nation and into what might have caused it, preferably with analysis beyond the six week point. Fin.

However, the NHS hospitals and drugs datasets appear to offer some insight into the health (or otherwise) of the nation, and I’ll explore some other population morbidities over my next few posts.

Amanuensis is an ex-academic and senior Government scientist. He blogs at Bartram’s Folly – subscribe here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

posts like this are getting harder to read. Any sensible person can see the need for a form of acceptance that harm has been done and that the sooner it happens, the better for society but such is the depth of the problems that allowed this to happen, I can’t see it ever happening. That will create a separate and additional set of challenges.

Agree. How much evidence does one need of the sun rising, the sun setting, the lunar cycle, or the fact that the Stabbinations have killed tens of thousands,probably 1-2 million injured in various ways; and are entirely useless against anything except making money, poisoning your blood and potentially, killing you via many mechansims, both fast and slow.

Agree. If we can see the harms, with our knowledge of anecdotal evidence and the odd article, then the government very definitely know the harms (indicated by their fixed and fiddled and missing data). But the harms will never see the light of day. After all:

Astrazeneca withdrawn – nothing in msm

boosters withdrawn for under 50 – very little in msm

1st doses withdrawn for under 50 – nothing in msm

Lisa Shaw and other deaths caused by the vaccine – nothing in msm

we are better to put this behind us and focus on what the future may bring.

The future is likely to bring new ‘pandemics’ each with its own tailor made set of vaccines.

New ‘pandemics.’

Billy’s next brew is due for release later this year or next. The “vaccine” factories are either built or under construction.

And the new WHO agreements will mean that escaping the ‘vaccines’ won’t be so easy next time.

This is what I meant by look to the future, I wasn’t being optimistic!

The problem you have is a huge group of committed medical drones on denial.

In mid 2021 I remember seeing an elderly lady with Shingles. Not rare in her age group, and it developed a month after her last vaccination. However, her husband died of a massive pulmonary embolism 3 or 4 days after his vaccination. It could still have just been chance.

The problem for me was that she was told absolutely and definitely that thus had nothing to do with the vaccination.

Without a pathological examination that cannot be anything but a barefaced lie.

Use of specialist drugs to treat ‘serious shingles’ us up considerably since 2021, and still rising.

A friend of mine died within 24 hours of a booster, massive heart attack. Coroner refused a post mortem – coincidence.

Yeah right

What will happen (at least in the UK) is that an Inquiry will be initiated, the terms of reference of which will be to look at “all” aspects of the Covid fiasco. “All aspects”, of course, will include distractions such as race, gender identity, Windrush, vaccine-hesitancy, disinformation and social media, while ignoring the various room-occupying elephants, such as novel vaccination, early treatment protocols, lockdowns and Midzolam, not to mention the trillions of dollars sloshing around the world’s pharma-political complex.

The distractions will be numerous and heavily armed by the media and the Cabinet Office. I presume the CO has all bases covered and battle plans have been war-gamed. “Never set up an inquiry unless you know in advance what its findings will be.”

The only way MPs would get a stroke would be too much clapping for Zelensky

Stand in the Park

Make friends & keep sane

Sundays 10.30am to 11.30am

Elms Field

near Everyman Cinema & play area

Wokingham RG40 2FE

The NHS appears to be worried enough about it to spend money on advertising. Recently they have been advertising strokes on GBN to encourage early reporting of them.

Not just GBN, stroke & other health ads are all over the airwaves these days. I even saw 2 BHF ads back to back plus a third in one ad cycle the other day. Kids’ myocarditis, shingles, life insurance are all up too. They seem to have replaced the previously wall-to-wall erectile dysfunction ads.

The erectile dysfunction data are very odd. There’s a hint of a problem in the UK prescriptions data, but nothing substantial (fnah). OTOH, there’s emerging data from the US suggesting sales of viagra (well, sildenafil) increased 10% in 2021 cw 2019 and 2020 (no particular effect of lockdown). I don’t have data for 2022 yet.

Of course, men with ed find it a bit embarrassing to visit a GP about this problem, so it might take some time before this issue is fully understood.

The above data will not surprise anyone. Steve Kirsch offers some supporting evidence in the form of the US Medicare database stats. This is very interesting and revealing stuff. He had Dr Clare Craig and Professor Fenton check it before he shared it. As per usual, all the graphs are going the wrong way!

”This may well be the most important article I’ll write in 2023.

In this article, I publicly reveal record-level vax-death data from the “gold standard” Medicare database that proves that:

If there is one article for you to share with your social network, this is the one.”

https://stevekirsch.substack.com/p/game-over-medicare-data-shows-the

I live in a small, private Close of 19 houses. They aren’t age restricted but most of the owners are over age 70. In the past 18 months four jabbed residents have had strokes (more than one each) – three are now dead, the remaining one is in a very bad way and could go at any time.

In the previous 3 years I have lived in the Close I don’t recall a single neighbour having a stroke.

This is Mis-, Mal- and Dis- Information as it has not been

1. approved by HM Government and

2. brought to us by BBC.

It is also mis- & malfeasance in public office. But according to the police, there is no evidence of a crime which needs investigating, let alone putting said evidence to the CPS for consideration of a prosecution, which says everything about cover up & corruption on an institutional scale.

When you report mis- and malfeasance to the the police they always say there is “no evidence of a crime” and mark such reports as “No Further Action”. This happens even if you take along a letter signed by the perpetrator admitting what they had done. If you want some light relief you can try reporting the police to the Independent Office for Police Conduct, based on Dereliction of Duty to Investigate, in which case you can get a fancy certificate saying “No Further Action” printed in 72 pt Bold Comic Sans Font on parchment and a visit from a police officer when they hand you an ex parte super-injunction. If you complain about all this to your MP they will acquire a letter from a Cabinet Office minion politely but verbosely saying that there is “nothing to see here” and your MP will forward it to you and impolitely tell you you are a “conspiracy theorist”, whereupon Special Branch will come in person to hand you an ex parte hyper-injunction. I guess the next milestone is The Gulag or being sectioned, cancelled, found dead in woodland, or demonetized on TwitTubeBook, sanctions which in the UK these days are pretty well interchangeable, and random depending on one’s celebrity status and which AI bot is scanning one’s posts.

This is horrific.

A wonderful analysis which the RPTB will take zero notice of.

.Re the 4th paragraph, I believe that there is plenty of scientific evidence available to show how all CV problems can be caused by the mRNA jab :-

Basically the mRNA is designed to makes the body produce the infamous Spike which the immune system will recognise as foreign and dangerous and thus elicit the desired immune/memory response.

All well and good thus far. But, as explained by Sucharit Bhakdi and others over 2 years ago, artificial spike can be produced anywhere and if it is produced in endothelial cells your immune system will attack it, clots can form and voila – you’ve got a problem.

For a more detailed explanation of the scientific evidence proving potential harms please read section 14 of this paper :-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S027869152200206X

For the rest of the health delights in store, read the rest of it. The paper has never been challenged.

If only, as Amanuensis says, there could be a matched cohort study of the vaxxed v. unvaxxed (and as regards all health/death outcomes).

All the necessary data is there.

But it will never be honestly released.

Neither will there ever be an announcement that vax safety will ever be looked at.

Because that could undermine public confidence in vaccination – and that would never do because all vaccines are safe and effective. Fact.

The official line is that it is covid itself causing CV problems. That is easily disproved eg lack of footballers keeling over during the pandemic but pre vax. But mainly by scientific fact. Post mortems prove that it is the vax spike – as opposed to the covid spike causing the problems – due to the absence of nucleocapsids. See Ryan Cole MD and others on this.

I have posted regularly that the caseload in the community stroke rehabilitation team where I used to work has been changing in demographic, increasing in numbers, dependency & that the length of time with the team has been severely reduced since all of this began.

During lockdown & until Autumn 2020, the caseload was lighter than usual & staff had insufficient to do. Then the usual winter increase in referrals until December 2020 when referrals started to increase & haven’t slowed down. This is directly from my boss.

The criteria for referral are less than 6 months post onset of stroke & to have some rehab potential. The latter seems to have gone out of the window as many of the referrals are what we term heavy strokes ie bed bound & take 2 -3 staff to carry out a therapy session. These patients are the slow burn recovery types & will make only minimal progress, if any in the now 8 weeks allotted to the time with the team – cut from 6 months since autumn 2020.

Pre 2020 there was already a shortage of long term rehab services for these patients, many of whom continue to make progress, albeit slowly, years after the event. Staff with the requisite level of expertise were in short supply, even worse now & coupled with NICE diktats, evidence based practice & changes to training that teaches that functional therapy is the only way rather than treating the root cause of the impairment ie weakness or a specific cognitive pathway, condemns the patients to a lifetime of disability & frustration.

I was fighting the functional is the only route or give them a communication book & all will be sorted route for years before all of this, as it meant the patients could be seen, assessed, “treated” & discharged in just a few weeks as a way to get through the stupidly high caseloads. It was a tick box exercise as the communication book was invariably in a drawer or a pile of papers if it hadn’t been lost when the patient was reviewed. If the patient cannot link a picture to a concept, how the hell can they use a book of pictures to communicate with??? Bloody basic yet I was told to do this. I never did. Total insult to the patient & their dignity. Amazing what a bit of intensive treatment of the cause of the problem can do to improve the quality of life.

With the unknown long term impacts of these bioweapon injections on the cardiovascular system, I fear that the future for stroke patients & their families will become worse. Much more worse than currently.

Stroke has always been a Cinderella service as it’s not sexy & there’s no magic pharma bullet cure. A third of stroke patients die, a third make a reasonable recovery & a third make a poor recovery, in reality existing. Many of this latter group wish that they were in the first third. A harsh, hard reality from the coal face of just how badly failed stroke patients have been & continue to be so by the NHS.

Having said all of that, I loved working with & making a positive change to the quality of life of my stroke patients. A huge, huge privilege to be permitted to do so.

Thanks for that post. It really brings home how the increase in strokes is an increase in real people having a real serious (often fatal) problem with their health. This is something that shouldn’t be forgotten.

Have you seen a change in the age profile of new patients with stroke (apologies if you’ve posted this before)?

My boss has reported that the demographic is trending younger, but we always had a younger cohort dependent upon ethnicity & location within the city. Alcohol & drug use contributed to the younger strokes as did poverty, poor housing & crap food diet, but the teen & early 20s strokes tended to occur due to a previously undiagnosed underlying health issue.

I can no longer access the stats to support this.

“Surely the population of the USA would be very keen to have this information.”

No, it isn’t very keen. They’d all rather forget it. Too painful.

“… it didn’t actually include any data to support this reassurance.”

And is this not the very essence of the entire, ridiculous covid19 saga? Did they ever, in the past 3 years, provide any data to support their reassurances? No data to support incarcerating people in their homes, no data to support masks being of any use, including when worn alone driving in your car or walking alone on a deserted beach, no data to support staying 1 foot, 3 feet, 6 feet apart (differed per country) to avoid catching a virus that spreads through the air (I do believe MIT came up with data that indoors the virus spread beyond 60 feet).

Not only was there never any evidence that the poison worked, it was the exact opposite – from people collapsing immediately after being vaxxed, to dying in their sleep within a few days, to people falling ill with the lurgy within a week or 2 of being vaxxed, and falling ill with the lurgy again and again after each ‘booster’. Of course they would claim ABV – it was bad enough they got away with sticking this garbage into people multiple times without any proof it did anything, but look for evidence that it actually caused harm – why would they? Public authorities, medical ‘experts’ and the public at large were more than happy to follow a repeated lie – after all, it was said again and again and again by major figures across the media that it was safe and effective – it had to be true. Why bother using your own eyes and common sense?

What I really want to know – and what must be essential to know in terms of how long there is an elevated risk – is how long the mrna keeps circulating in the body? I’ve seen 2 studies, one saying they found it up to 28 days after poke (28 days was the end of the study), another up to 60 days. If this time might be longer, if the spike protein lingers and/or is reproduced for a longer period of time than originally thought, this must affect the development of adverse effects. And I would bet that they do have these data – there is a reason why it is not being published.

The reports on mRNA longevity tend to not differentiate between viable mRNA and fragments of mRNA.

I’d suggest that the current data shows that viable mRNA can still be found after about 20-30 days, but after that it is only fragments. This is very very concerning, as we were originally promised that the mRNA would only last a few hours, and the longevity of the mRNA (and thus protein production) is of pivotal importance in understanding the immune response.

That there were no pharmacokinetic and biodistribution studies done for the covid vaccines is truly bizarre — these are the cornerstone of understanding drug effects.

Thanks. Do you know if there are reports that have looked for presence for, e.g., a 6-month time period? Or is it pretty much established that viable mrna will by and large no longer be found after 30 days (which is, after all, only 15x longer than they originally said – no wonder the CDC wiped that from their website).

Do we know whether mrna fragments themselves can cause problems or is it just harmless (hmmm) junk floating around in the body that eventually gets eliminated?

Do you know how long the spike protein stays in the body? Do we know whether the vaxx spike protein lasts longer than the viral spike protein? Wasn’t there some talk that the vaxx s protein was more stable and therefore remained longer?

Do you know whether Novavax is linked to higher strokes? I know there’s less data as it hasn’t been used as widely, but I have read several times now about Novavax and myocarditis. As it does not have a spike production mechanism, does this mean the LNP are implicated in the myocarditis due to wide-spread distribution throughout the body?

As for biodistribution – they must have plenty of data on that from prior research. Surely the actual LNP/mrna mechanism determines that, not the specific mrna payload itself?

I don’t know this information.

Neither does anyone else (well, perhaps some in the pharma companies, but they’re not telling anyone about it).

FWIW, I believe that it is quite likely that the problems with the vaccines are as much to do with the antibodies they produce (including autoantibodies) than with the spike protein itself. This would be a problem, as these will likely be regenerated upon each covid reinfection (which will be at least annual).

Amanuensis, I think that you would benefit from & contribute greatly to MD4CE group. Members include the cast of cancelled & censored degenerates & troublemakers who have been questioning this since the start of the scamdemic such as Wolfgang Wodarg, Dr Mike Yeadon along with lawyers, scientists, pathologists, engineers & other medics. I belong in the troublemaker category! How can I contact you directly so that I can forward your email to the founder of the group to issue you with an invitation?

BB

Hi BB — get in touch with Will at Daily Sceptic — Cheers.

Will do.

BB

There was a biodistribution study in rats done at the insistence of the Japanese government (attached) which showed very concerning distribution after 48 hours but that is all the biodistribution data we have apart from the autopsy studies done by Arne Burkhardt in Heidlberg which show distribution of the S1 protein but no N protein in the cadavers of folk who died suddenly post injection.

Isn’t that the study Dr Byram Bridle was talking about during this interview almost two years ago?: –

https://www.bitchute.com/video/N5UAQT3s31TY/

Most likely. It’s the only biodistribution study which has been seen publicly, leaked to the public domain as it was meant to remain confidential. Someone somewhere has a conscience.

Geoff Pain on Substack https://geoffpain.substack.com has written several detailed articles including some on elements within the injections that could be causing some of the serious health issues including death. (Spoiler alert: there are many). He has highlighted in particular endotoxin contamination which would explain potentially some of the ‘bad batches’. These products were not terminally sterilised ( as traditional injections are) and given the rush and using uninspected facilities with perhaps new staff, new processes it would be easy to see that things could go wrong. There is also a suggestion that fever figures were ‘fudged’ by Pfizer (a typical endotoxin reaction). This is in addition to the 50% mRNA purity figure for release which of cou8rse means that 50% was degradation or other contamination! There may also be a connection between endotoxin levels and spike protein but that is speculation at present.

This link https://www.aimsib.org/2022/11/20/la-contamination-par-les-vaccins-a-arnm-est-elle-biologiquement-plausible-a-partir-dun-sujet-vaccine/ is to a French article which google should translate. It is well referenced and tackles ADME and points out that it should have been done and that it definitely should be done still and before any further RNA therapies are considered. My personal view is that there should be a complete ban on any such therapies.

To have modified the uridine component to pseudouridine to intentionally allow it to remain for longer in the body and then to not have tested to see just how long that actually is, is yet another measure of how desperate people were/are to have us all injected with it.

I’m sure that any mRNA fragments will be broken down harmlessly by the immune system even if they manage to code for anything more undesirable. Lol.

Even this assumes that the mRNA actually codes for the intended spike in the first place.

Apparently, and because mRNA is so delicate there is a danger that it often fails to code as intended anyway.

Never mind though, nobody knows/cares what the harmful effects of that may be.

A study of biopsies (taken for other reasons) sitting in pathology labs may be worth doing (with patient consent).

Hopefully there’s a slim chance that the Thai government might break ranks after the collapse of the Thai princess?

A stumbling block there might be that the Thai king made money by selling the Astrazeneca concoction.

Regarding data that proves the increase in strokes is due to the bioweapon injection, publicly available evidence in Massachusetts is being collated by John Beaudoin Snr. He’s trawled the publicly available death certificates & linked each one to a VAERS report where possible. He has found huge increases in deaths post bioweapon injection rollout due to blood disorders. You can find the body of his work here: https://coquindechien.substack.com/

And watch a presentation of his work here:

https://rumble.com/v1uhm0w-john-beaudoin.html

Re MD4CE group you can find a recording of our biweekly meeting presentations here:

https://rumble.com/user/cbkovess

Some brilliant presentations by exceptional folk fighting for the welfare of us all.

Yet another most welcome contribution from you. Many thanks for continuing to shinea light into the dark spaces.

Thanks for the article, as always.

In 2015, I was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation and prescribed Warfarin. My INR never stabilised – the dose was continually revised on an almost weekly basis. Some time after that, it was suggested to me that I switch to Apixaban – a Novel Oral Anti-Coagulant (NOAC) – novel? It might only have been subject to 10 years or so of trials, then some real world experience . . .

So – there may be, within your figures, a number of people who have been switched from warfarin to apixaban. Therefore, any reduction in warfarin prescriptions should be subtracted from the figure for apixaban. (If I’m wrong, and all suitable apixaban candidates had already been switched, it will have no impact on the figures.)