Sometimes we hear the following argument:

Wokery is Cultural Marxism. Originally Marxism was about class struggle and oppression. What happened in the late twentieth century, with the breakdown of old heavy industry and the decline of the old working class, was that Marxists began to study other forms of oppression: and hence other objects of oppression, which they understood in classical Marxist manner as being oppressed by the capitalist system of expropriation. Wokery is Marxist because it continually talks about capitalism, neoliberalism and so on as cause, and various forms of oppression as consequence.

I don’t like this argument. I think it is slack and careless. This is because it involves a misrepresentation of Marxism – and this has to be said even before we say that Marxism necessarily involves a misrepresentation of Marx (as Marx himself said when he said he was not a Marxist).

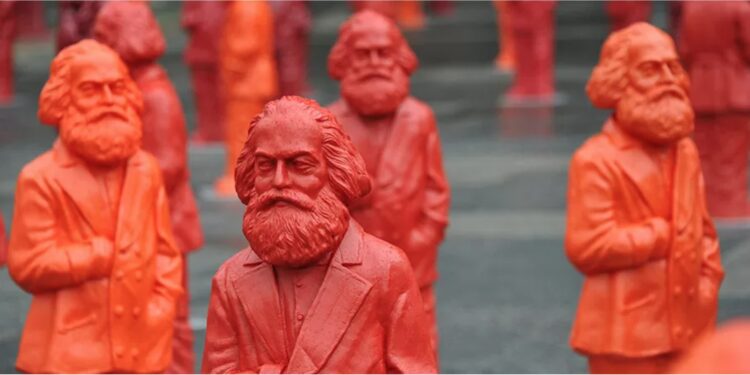

So let us consider Marx, and then consider Marxism.

Marx, broadly speaking, was an extremely penetrating and weighty thinker who attempted to build a singular and systematic explanation of society out of German philosophy, French socialism and English political economy. These three elements were compatible in some respects, but not in others: Hegel and Adam Smith would have been appalled. Marx forced the three elements together, but as Gareth Stedman Jones has shown in his long biography of Marx, he did so in such a way that his theories were continually undermined by the fact that history appeared not to be playing along with those theories: so he seemed, as he tried to ring the changes, to have developed as many as three different logics within his system. In addition, Stedman Jones, to the displeasure of Marxists, has concluded that Marx was, ultimately, only attempting to work out what to think “after Christianity”: so that in fact the original set of problems he wanted to deal with were religious rather than secular, social or political.

Marxism, on the other hand, is a distillation of a sharp economic and political doctrine out of Marx’s complicated and multifarious works. This is the system which was initially promulgated by Engels, then Kautsky and Bernstein, and adapted in various ways by Lenin, Trotsky, Luxemberg, Sorel, and Lukacs, and which, in Britain, of course, was defanged and renamed by the Fabians: Webb, Shaw and others, including for a time Wells – which is why Marxism never had much direct purchase in Britain, despite intelligentsia revivals in the 1930s and 1960s. Fanged ‘Marxism’ consisted of, broadly speaking, the expectation, courtesy of ‘dialectical materialism’ (that is, of the dynamic history of economic processes of production and distribution), that the contemporary control of the economic and political system by the ‘bourgeois’ class of capitalist oppressors would experience an inevitable crisis as a consequence of the working out of its own logic – a crisis called a ‘revolution’ – which would lead to the emancipation of the ‘proletarian’ class, and thus an end of all oppression, immiseration and alienation. This would be a revolution-for-all, since even the capitalists, though not oppressed or immiserated, were and are, even now, alienated. Therefore, the emancipation of the proletariat would be, no matter how it was achieved, the emancipation of everyone. It would be a universal revolution.

The ambiguities of all this are obvious to any undergraduate who has to write an essay about it. Even Marx was sometimes unclear about whether this great revolution was the end of history or not. According to his original assumption about the persistence and continuity of class struggle in history, he thought it was not. But according to his theory of emancipation, he thought it was. (Marxism is basically Waiting for Godot, rewritten as if Godot has come, but as if nothing has changed despite his coming: Beckett’s “Nothing to be done” being a happy translation into English of Lenin’s “Something to be done”.)

Anyhow, Marxism is magnificently complicated. Its western varieties can be studied in Kolakowski’s unsympathetic Main Currents of Marxism and Perry Anderson’s sympathetic Considerations on Western Marxism. And that is before we consider Eastern Marxism on the one hand and the defanged Fabian varieties which have given us ‘social democracy’ on the other. But if anything, Marxism has become even more complicated as the original 19th Century confidence in it as theory and the subsequent 20th Century confidence in it as practice has faded: as the 1968ers, the Badious and Zizeks and Giddenses and Agambens have cascaded all over the place, turning Marxism into a Maoist-Lacanian-Blairite-Foucauldian academic commonplaces of myriadic confusion and complexity. And even this is before we get to the 2008ers (zéro-huitards): who would be condemned by all of the 1968 generation (except in so far as they prioritise wanting an audience over maintaining some sort of quality control). The 2008 generation is the one which has knitted all the new enthusiasms of the 1960s and 1970s together, all those enthusiasms of race and sex, and formed them into a finally unified ‘intersectional’ movement, usually symbolised by a rainbow.

Even the story I tell here seems to suggest that adding Black to the Union Jack and adding Pink to the Pound are the latest manifestations of Marxism. But they are not. For we have to recognise two things. The first is that rainbow intersectionalist Wokery is much more Liberal than Marxist. The second is that Wokery is itself susceptible to a harsh Marxist analysis. These two claims are short and simple and, I think, irrefutable.

First, Wokery is Liberal. Just became something is about ‘oppression’ does not mean it is part of a Marxist politics. We had attempts to deal with oppression long before Marx. Consider Spartacus or Tiberius Gracchus or Wycliffe. And it is in fact the great ideological strand we now call ‘Liberalism’ that brought into modern politics a consistent and coherent concern with the disadvantaged and with minorities. Byron, who helped found the journal The Liberal in the 1820s, was an enthusiast for an independent Greece, and so more or less invented the romantic politics of the underdogs of empire. Much modern Wokery is simply the Byronism of a later age: with Blacks or Trans instead of Greeks. John Stuart Mill in On Liberty outlined the basic arguments for the liberal hope that freedom of discussion – that is, not eliminating the views of minorities – would lead to moral and scientific improvement. His great enemy was what he and Tocqueville called “the tyranny of the majority”. For centuries Liberalism has been opposed to the (unenlightened) majority and in favour of (enlightened) minorities. It is a form of aristocracy twisted to bring it into the democratic age. And surely this is at the intellectual root of Wokery. (And this is the case even though modern Social Justice Warriors are now a species of Liberal so sure of themselves that they feel entitled to suppress freedom of discussion.) All the modern intersectional obsessions – racism, anti-Semitism, empire, slavery, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, islamophobia, etc. – are, in the West at least, simply outgrowths of a Liberal inclination to side with minorities against the majority. The whole thing is more Liberal than Marxist, even if Marxists have come in afterwards to offer grand and dubious explanations for what is going on.

(It is worth noting the grotesque irony that this Liberal siding-with-minorities-against-the-majority has become a majority position. This paradox is causing almost all the confusion currently seen in our culture.)

Second, it is possible to make a harsh Marxist analysis of Wokery. Marx himself was partly responsible – along with Napoleon – for turning the silly word ‘ideology’ into a word of sharp political significance. Napoleon called his enemies idéologistes; and Marx, not to be outdone, used the word Ideologie for everything he was opposed to. However, unlike Napoleon, Marx had a theory of ideology. His theory was that ‘ideology’ was the intellectual superstructure generated by a dominant class (or the lackeys and lickspittles of that dominant class) to justify its domination: it was, as he also put it, a “false consciousness”: incantation and intoxication to create the dream-like haze which would enable the machinery to do its inexorable work. The bourgeoisie believed in their intellectual justifications not because they were true, but because it served their purposes to espouse them, to educate their successor generations into them, and even to create a system of belief for them.

Now, what is Wokery but an elaborate and radicalised set of ideological beliefs designed to defend certain novel changes in the elite systems of our civilisations? No doubt some of the Woke themselves feel marginalised: but they are usually either the very young or the very radical or the very poor, whereas it is obvious to those of us who have never had any interest in Wokery that it is most importantly an extremely nasty and devastating set of multipurpose weapons in the armoury of the new elites who have taken over our institutions in the religious, political and moral vacuum which has been British culture since the 1960s. British culture is not without its distractions or charm: antique heritage on the one hand (Stonehenge, the Queen, St Paul’s) and recent heritage on the other (Red Buses, Sir Paul McCartney, the Shard): but though it has some aesthetic appeal and much to offer by way of comfort, it has no soul. The culture is a sort of religious, political and moral Flatland, levelled down or levelled up (it is all the same) by relentless think-tankery, management-consultancy, middle-management and human-resourcefulness. Whatever most of the public figures, politicians, journalists, academics and scientists (and especially any scientists who happen to appear on a screen), believe is not something they conscientiously believe: on the contrary, it is ‘ideology’ in Marx’s sense. Wokery is the ideology, the bricolage ideology, of our new massed state-and-corporate regime. And surely COVID-19 has revealed to us all that despite the beery and jolly atmospherics of Liberalism which still befog and befoam the modern British mind, there was an astounding ideological ‘mass formation’, as we now say, as everyone came to agree about the succession of dubious and dangerous protocols wheeled in by unscrupulous amateurs and even more unscrupulous professionals to deal with an innocent virus.

Marx enabled some – like Agamben (also influenced by Foucault and others) – to keep their heads. Agamben was almost the only public intellectual of any weight who came out like Jeremiah during the pandemic. So we cannot blame Marx or even Marxism for everything that is going on. Marx had a good eye for the dynamics of power, and even if his false consciousness about his own moral sympathy for the underdog led him astray, he himself, had he been alive in our time, would have asked, as Lenin did later, who was benefiting in what way from whatever all this ideological fanfare was concealing in plain sight?

It is true that most Marxists have not done well during the COVID-19 crisis. Although they are generally fond of criticising corporations, they do so from a point of view which opposes acquisitive and rapacious corporations to an ideally redistributive state. This is a distinction which was always hopeful, if not completely fictional; and in our age in which states and corporations have formed grandiose and complex alliances there is no simple way of distinguishing ‘public’ and ‘private’. Anyone who claims to be able to distinguish them is lying, or simplifying to a fault. And so most self-styled critics of capitalism have tended to be the most abject supporters of the corporations which were responsible for vaccines or which benefited from lockdowns. These critics simply switched off their suspicion of corporations for the sake of the virus. Plus, they thought that there was something beautifully anti-populist and anti-parochial about fighting a virus: just as there is in fighting climate change or fighting exploitation and expropriation. But this universal feelgoodery is not Marxism: it is just the usual thoughtless elite Liberalism. Consider how thin the critique of capitalism must be, that it could so easily collapse in the face of COVID-19.

It wouldn’t surprise me if one day the Cold War might come to be seen as a war between two equally bad systems: in which the one in the West was only infinitely slyer and subtler than the one in the East. The propaganda in the West must make the Chinese gasp in admiration at its sophistication. Be that as it may, there is certainly no point talking about ‘Cultural Marxism’. The word ‘Cultural’ empties the word ‘Marxism’ of any significance. It is likely that anyone who uses the word ‘Marxist’ is simply using it as a term of abuse, like ‘Fascist’. So be it. But be aware that you are using the term as a term of abuse. And you are obliterating any attempt to make sense.

One more thought. Bring Marx back from the grave. Would he not say that post-Christian modernity has developed an even subtler ‘opium of the masses’ than Christianity – in this godless, scientific, hypocritical, oxymoronic, ‘sustainable’ and ‘progressive’, irritable, mental-health-obssessed, aggrieved, complacent and privileged rainbow religion?

Dr. James Alexander is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at Bilkent University in Turkey.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Of course ‘Marxist’ and ‘Fascist’ are terms of abuse.

Simply consider what atrocities have been committed in their name to understand why.

Using those words can make perfect sense where those so accused have proved themselves well worthy of abuse.

A perfect example is the current ‘democratic’ socialist fascist government of this country.

Another is Hancock. A better example of a contemporary British fascist would be hard to find.

I thought Marxism was when a man sleeps with one of his servants, gets her pregnant then refuses to take responsibility for the child.

Marx himself was apparently a “let it rip” kind of guy when it came to infectious disease.

Jesus, what a tedious piece.

In short, wokery is not Marxist because its elitist. And liberalism is elitist, not Marxism. Marxism is for the plebs.

My rebuttal is this: bollocks.

Liberalism is about the the freedom of the individual. Marxism is about collectivism. One of a number of collectivist ideologies.

Collectivism is all pretty much the same. It’s supposed to be about what is good for everyone, but in the end it’s always what a few decide is best for everyone. And it becomes tyrannical very quickly because it demands everyone play along because otherwise it doesn’t work. It’s a convenient ruse for contoling others.

Collectivism attracts people who crave controlling others, love telling others what to do.

That’s wokery. Telling others how they have to behave, what they have to think. Control, control, control.

Marxism, socialism, wokery, same crap.

“what a tedious piece.”

Wholeheartedly agree Stewart. An essay intended to hilight the author’s breadth of reading but which ultimately shuffles around taking pot shots at as many topics as possible.

This essay is a lesson in how NOT to write. Word diarrhea of the worst sort.

Am I any the wiser for reading this? I’m bloody bored I know that.

I’m guessing Saturday nights in Bilkent leave a lot to be desired.

Me too and very pleased I only had enough brain cells to study Biochemistry and Physiology, and not enough for Political Science

I wonder if the word Liberalism was misused because in UK it generally means libertarian but in US it means progressive/socialist? Almost opposed definitions.

Excellent book by Jonah Goldberg called Liberal Fascism going into how similar themes drove the Progressives (Liberals), fascists and communists the late 19th and early 20th century.

Includes the fact that Mussolini was a member of the Italian Socialist Party and Editor of its newspaper, Avanti, between 1912-1914 and left because of his support for Italys entry into WW1.

What a shock he was a lefty ….. of course not.

Liberalism is about the the freedom of the individual. Marxism is about collectivism. One of a number of collectivist ideologies.

And what precisely is collectivism?

Compare:

The volk (people) is more important than its individual members. The value of someone is by-and-large what services he can render to the community. All people are unique and hence, in order to serve the community best, each and every member must be given the opportunity to develop his full potential.

[Paraphrase from Mein Kampf but this is really how the army of the German empire was suppose to work, also called German, as opposed to Marxist, socialism]

versus (the modern, liberal approach)

By and large, people are all the same and no individual matters individually. Just throw them all into the water. Some of them will then drown but this doesn’t matter, more than enough will survive. Whoever gets out first on the other side of the river will receive the special price. We don’t really care what happens while they’re in the water.

This method has a tendency to select people who – instead of doing something heroic and special themselves – employ underhand tactics to prevent others from developing their full potential so that they end up winning for want of competitors.

Which approach values the individual and which doesn’t?

“as the 1968ers, the Badious and Zizeks and Giddenses and Agambens have cascaded all over the place, turning Marxism into a Maoist-Lacanian-Blairite-Foucauldian academic commonplaces of myriadic confusion and complexity.”

WTF?

Xactly. I just can’t get it up for woke. Zzzzzz

”Woke me up before you go go”

Wowsers, four articles today all about the same subject. Hope tomorrow brings a less woketastic day in DS Land. I do fancy one of those ”Awake not woke” shirts JP Sears has for the summer though. ”We’re woking in the aaaiiirrrr…” Anymore for anymore?

Is this the tone being set by the new editor perhaps? Nick Dixon doesn’t strike me as being quite as tenacious (and wilful – I had a stronger word in mind) as Toby Young.

Imho, this site mustn’t lose its teeth, but I’ve also noticed the recent ‘placatory’ shift in tone.

Yes I’ve noticed that too. And speaking of which, here’s a ‘woman’ who absolutely illustrates what we’re up against just now. Well she looks like a Marxist to me…and as a feminist myself I wholeheartedly agree that there is just too much toxic masculinity in the water nowadays.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RjXszNZW7nc&ab_channel=AwakenWithJP

I don’t think it really matters – woke and Marxism have such flexible and context dependent definitions anyway. What does really matter is that they both contain a collectivist view of society based upon group identity, and entail totalitarian government.

JS Mill’s warnings about the tyranny of the majority did not represent an unconditional endorsement of minority rule as the author implies. Like Orwell later on, he was just a man who understood tyranny when he saw it.

He had something pertinent to say about ‘cancel culture’ too:

“The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.”

-On Liberty.

I stopped reading here.

Marx, broadly speaking, was an extremely penetrating and weighty thinker who attempted to build a singular and systematic explanation of society out of German philosophy, French socialism and English political economy.

Marx was a 2nd rate intellect who never worked, and made up his data.

Wokeism is Cultural Marxism which seeks to destroy family, genders, normal sexuality.

Awesome article, thank you.

So let’s just call it Socialism – elevating the State over the individual by fragmenting society into conflicting groups; and central planning and control of the economy.

Socialism keeps reinventing itself under new names and cults in order to deceive: Marxism, Leninism, Stalinism, Fascism, National Socialism, Social/Liberal Democracy, Environmentalism, Wokeism, Anti-Fascism, Social Justice.

The idea that the state is a superorganism composed of individual humans and one of mankind’s great achievements was formulated by Hegel, ie, it’s older Socialism and Marxism. By that time, it had already been around informally since at least the time of the Greek city states. Central planning of economic activities to increase the wealth of the nation was popularized by Jean-Baptiste Colbert during the reign of Louis XIV in France (mercantilism). Serious attempts to abolish it again on the grounds that this would improve the economic situation didn’t really start until the 19th century.

The grand theory of the world according to US neoliberals is really just a grand display of their own ignorance about European history. That’s one of the reasons why it it practically pretty useless.

James Lindsay argues Hegel was a ‘sorceror’ rather than a philosopher …. fascinating tracing back to gnosticism and hermeticism (beyond me at this stage but compelling hooks in the argument about man being God which does ring true with regard to Hegel and many of the evil totalitarian schemes).

Wokeism is the unholy bastard child of Cultural Marxism and Neoliberalism. The cultural Marxism controls people’s behaviour and speech, while the neoliberal aspect protects the increasingly mercantilist ‘markets’, which are far from free. In essence, the neoliberal aspect allows for steady supply of cheap labour and off-shoring and the cultural Marxist aspect condemns anyone who complains about it as that week’s brand of ‘istaphobe!’

All this boils down to is that busybodies, curtain-twitchers and holier-than-thou types have moved out of their homes (and parish churches where they used to parade, with a fanatical glint in the eye, how much worthier they were than the rest of the congregation) and into positions of power. They’re a convenient footsoldier class, convinced of their moral rectitude, deeply voyeuristic and possessed of almost limitless control freaky. In a marriage, their behaviour would be condemned as ‘coercive’.

And as for the use of the term ‘Marxism’, a mutant offshoot is still a form of Marxism, the same way a Darwinist in the 1930s might have developed many different views from Darwin, but the starting point will still be Darwinian.

The modern societal movements want… need to control everyones’s behaviour at a micro level. Free will is an inconvenience, mavericks are dangerous: anything disruptive to the market must be quashed, so 15-minute cities, removal of travel ability, removal of freedom of speech all serve to keep us in our boxes.

You could say a redundant argument but I feel I need to respond …

Richard Delgado wrote Critical Race Theory – An Introduction – 2001 with Jean Stefancic.

He also attended the founding gathering of CRT in 1989 – here is a snippet from a transcript of an interview with him ….

“I was a member of the founding conference. Two dozen of us gathered in Madison, Wisconsin to see what we had in common ….. I had taught at the Uni of Wisconsin and Kim Crenshaw (she of Intersectionality infamy) later joined the faculty as well …… The school was a centre of left academic thought. So we gathered in that convent for two and half days, around a table in an austere room with stained glass windows and crucifixes here and there – AN ODD PLACE FOR A BUNCH OF MARXISTS – and worked out a set of principles …”.

The author may well be making a technical argument but I think the neo-marxists think there’s something pretty marxist-ish about CRT, Queer Theory and Wokery.

In my view James Lindsay has it right when he argues the architecture of Marx has been utilised by Neo-marxists to change from economics to other factors – race and queer being the primary ones impacting today.

Example:

Traditional Marxism

Oppressor – Bourgeoisie

Oppressed – Proletariat

Property – Capital

Ideology – Capitalism

Race Marxism

Oppressor – Whites

Oppressed – POC

Property (in this case cultural property) – Whiteness

Ideology – White Supremacy

Queer Theory (Marxism)

Oppressor – Normals

Oppressed – Ab normals (Queer)

Property – Normalcy

Ideology – Cis-heteronormativity

Strictly the author may be ‘technically’ correct but I think misses the point.

This is Marxism just wearing todays disguise.

Woke——–Express support for Free Speech publicly, but never discuss controversial subjects.——–A cautionary tale. —— I recall one time being in the old Yugoslavia, part of the Soviet Union. I noticed while walking through Belgrade to change currency that there were a lot of people going about their business but there was no “hubbub”. The people just seemed to be keeping their heads down and were mostly quiet. WHY? Were they scared to voice opinions? Did they think authorities did not like the idea of complaints and that people feared being reported as “dissidents”? I found it slightly sinister. I can see the western world turning into something similar, as our right to free speech is eroded and when it goes completely, we no longer live in a free country. And remember that “You don’t know what you got till it’s gone”

I’m puzzled by some of the negative and somewhat spiteful responses to this article. Although it is an intellectually challenging piece I thought it was lucidly argued, and explained how Marx’s complicated ideas were appropriated and further confused over time quite brilliantly. However, while I agree with the author that wokery is clearly not Marxist, I’m not sure that it can be described as liberal either, in the true sense of the word. In The Road to Fascism Simon Elmer argues that in its hatred of the working class, its suppression of debate, its normalisation of censorship and cancel culture, its ostracism of the non compliant and its adoption by government, corporations and the MSM, woke is better described as fascist.

I don’t think it’s really so puzzling. It’s the resentment aroused by someone who seems to know (and think) more than I do. (Who does he think he is?) Sullivan’s only puzzled because he isn’t made spiteful by resentment.