We’re now halfway through Advent, the time of year when Christians worldwide celebrate the latter stages of the Virgin Mary’s pregnancy and the upcoming anniversary of the arrival of their Messiah in tiny baby form. Thus it seems like a relevant time to discuss the section of the UKHSA Vaccine Surveillance Report that covers the impact of the vaccines on pregnancy.

The UKHSA started including data on pregnancy at the end of November 2021. Like all aspects of the UKHSA Vaccine Surveillance Report, it appears to have been included because the data conformed to the message being promoted by the Government, that is, that the vaccines were safe to be taken before or during pregnancy; I very much doubt that these data would have been included if there were significant negative outcomes being seen in the data.

From the start the UKHSA has focused on stillbirths and birthweight. The data that it does present are reassuring in that they suggest that the vaccines do not have any detrimental effect on these pregnancy outcomes, at least. That said, there have been questions regarding its presentation of the data that it did include. For example, it doesn’t offer any analysis of the data by the period within the pregnancy in which vaccination occurred. This is important because risks vary over the months of pregnancy, and a high risk in one period might be diluted by being mixed with data from other periods in the pregnancy that show no additional risk. There’s also the consideration of its use of cumulative statistics, that is, it often doesn’t offer month by month data but merely updates its total for each new report. Attempts at reverse engineering a monthly figure for stillbirths, for example, suggested that there had been an increase in the early months of this year, whereas this effect was masked in the cumulative data. It certainly would be far less suspicious if the UKHSA presented its data in a more straightforward fashion.

The big problem with the Vaccine Surveillance Report’s section on pregnancy outcomes is the selective nature of the data offered. The authors appear to have decided what we should be worrying about and then ignored everything else. In particular, they appear to be ignoring the health of the baby at birth (using ‘birthweight’ as a proxy of health is insufficient) and there appears to be nothing in the way of longer term assessment of the development of the baby once born. It is important to play close attention to the development of babies in their first few months of life, as it is only after 6-12 months that certain developmental abnormalities become readily recognised. For example, Foetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS, a developmental abnormality caused by the mother drinking alcohol during pregnancy) is often not recognised before six months of age (and sometimes not until some years after birth), despite it being a serious condition that is entirely due to abnormal development in the womb. It is of note that FAS was recognised as being a potential problem in the mid 19th century (and possibly was known as a potential problem for centuries before this time), yet it wasn’t until 1973 that the first rigorous study into this condition was published. It isn’t so much that medical research was slow in this case, but more that it can be difficult to identify problems in very young children even where the impact is significant, and simple observational studies are often not enough.

One strange aspect of the UKHSA’s data on births is that there appear to be missing data: Table 6 of the latest UKHSA Vaccine Surveillance Report, which provides monthly births totals from January 2021 to June 2022, suggests that 527,728 babies were born in England in 2021. However, the ONS believes that there were 595,948 babies born in England in 2021. It isn’t clear where this discrepancy comes from. Even stranger are the data on stillbirths – working with figures provided by the UKHSA suggests that there were approximately 2,050 stillbirths (this isn’t exact; it is computed from UKHSA stillbirth rates data, which give an overall stillbirth rate of approximately 3.8 per 1,000) while the ONS believes that there were 2,451 stillbirths in 2021 (a stillbirth rate of 4.1 per 1,000 births). Thus the UKHSA appears to be missing approximately 65,000 births and 400 stillbirths, which gives a stillbirth rate for the data missing from the Vaccine Surveillance Report of approximately 6.15 per 1,000 births. It is clearly very concerning that there are so many stillbirths in the data missing from the UKHSA report. Of course, this could be explained by the UKHSA and ONS having different definitions of what constitutes a ‘baby’. Nevertheless, I believe the onus is on the UKHSA to explain this discrepancy and it shouldn’t be ignored.

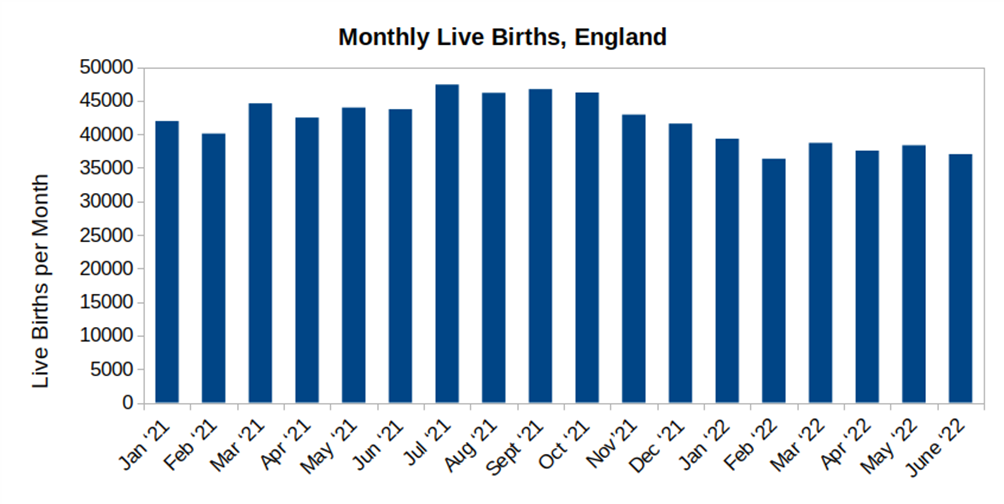

I’m sure that many readers by this stage will be wondering why I’ve not yet mentioned the elephant in the room – birth rates. Over the past few months there have been multiple posts online about an apparent reduction in birth rate during 2022. These data appear to be visible in the statistics available from Germany and Hungary to name just two of the countries that appear to be affected, and unfortunately it is also visible in the statistics on births in the UKHSA Vaccine Surveillance Report. From a background rate of approximately 45,000 per month in summer 2021, births in England fell to a low of around 36,500 in February 2022 and have since recovered slightly to approximately 37,000-38,000 births per month. These data suggest that birth rates have fallen by approximately 15%, comparing the period prior to November 2021 and after February 2022.

It is worth pointing out an aspect of these data even though it is ‘obvious’ – women are pregnant for nine months before they give birth, so whatever it is that might have caused this decrease can probably be traced back to spring 2021. Also, we’re now at the point where most new parents will already have been vaccinated at the point of conception of their baby, thus as the birth rate doesn’t appear to be returning to its pre-2022 level it is becoming more likely that if the vaccines are responsible for the reduction in birthrate that it will be an ongoing problem (compared with a transient problem if the vaccines only impacted on birth rates when given during pregnancy).

Other online commentators have suggested that this apparent fall in fertility rates is only because the UKHSA births data are preliminary, however, successive Vaccine Surveillance Reports haven’t seen updates in the births data of the necessary magnitude (e.g. the births figure for August 2021 was 47,157 when it was first published and was 46,149 in the latest update – a fall of close to 1,000 births). Note that while I discussed ‘missing data’ in the previous paragraph, these missing data are for 2021 and the issue with lower birth rates appears in 2022. For the other nations of the U.K., preliminary births data from Scotland also appear to show a reduction in births by around 10% in recent months compared with the 2017-2019 average, while data for Northern Ireland and Wales for 2022 don’t appear to have been made available yet.

It is important to state that there is no concrete evidence that the lower birth rates that are being observed around the world are due to impairment in fertility or increases in miscarriage and stillbirth: it might simply be a behavioural effect associated with lockdown or vaccination. For example, the birth rate problem might be a consequence of forcing young loving couples to not have any break from their partner for months on end in 2020, leading some to reconsider their future plans. However, a similar reduction in birth rates has been seen in Sweden, which didn’t lock down to the same extent as other Western countries, as described in a recent blog post by el Gato Malo – data from the Swedish Statistic Bureau show this significant decline.

It is also important to note that the apparent reduction in birth rates could be due to the Covid vaccines or Covid itself – while the lack of any real reduction in birth rates after Covid arrived on our shores but prior to the start of mass vaccination suggests that it is more likely to be a vaccine effect, this isn’t conclusive. In addition, human fertility is complex; the reduction in birth rates could be due to diverse factors such as an increase in erectile dysfunction or a decrease in libido.

Whatever the causal factors, it would be reasonable to think that there would be robust investigations into this drop in birth rates, but there are no signs of these investigations even though the impact by vaccination status should be relatively simple to study, at least compared with other factors (though underlying differences between vaccinated and unvaccinated cohorts would need to be accounted for).

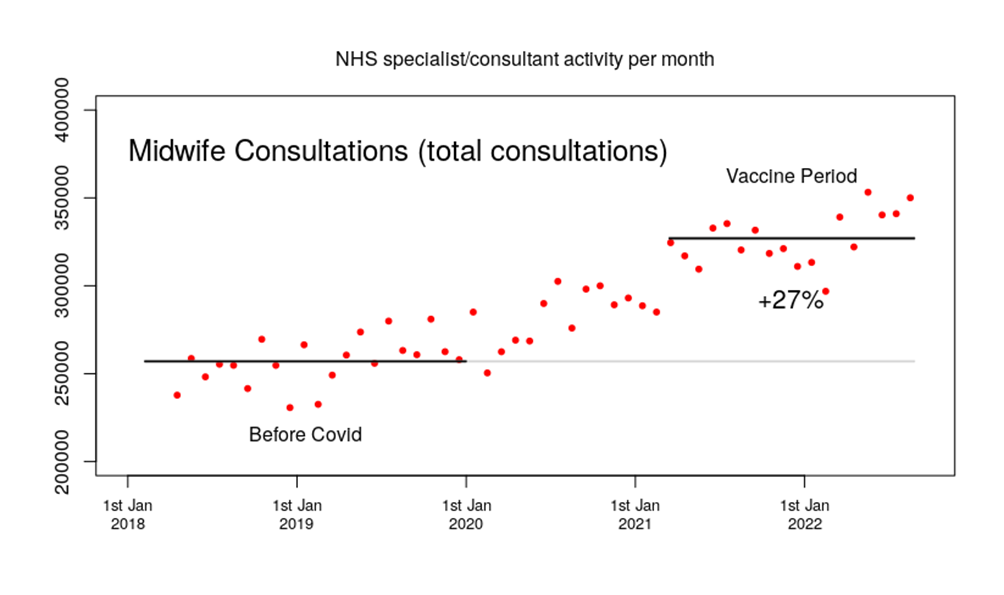

Another strange aspect of the recent births data for England is that they appear to run counter to data from hospital consultant activity over the same period. For example, midwives have seen increased activity even as birth rates dropped.

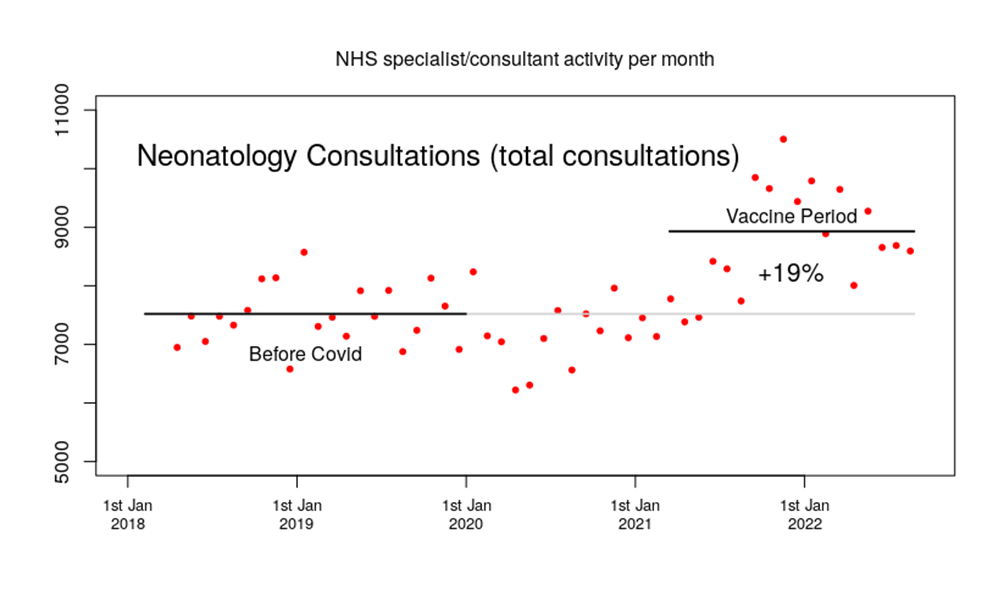

Even stranger, the same data source shows an increased workload for hospital consultants specialising in the newborn baby.

It isn’t clear why the midwife data shows their workload to have increased despite fewer babies being born. It also isn’t clear why there’s more activity by specialists in the health of the newborn, or whether this reflects higher levels of medical problems in full-term babies or an increase in pre-term babies (that said, data in the UKHSA Vaccine Surveillance Report suggest that there’s been no significant change in the proportion of babies being born pre-term).

Another important aspect that has been ignored by the Vaccine Surveillance Report is the protection offered by the immune system after natural infection. Vaccination, of course, offers the immune system ‘a taste’ of the infection without all the risks of actually getting infected, resulting in some level of protective immunity. In general, vaccination is preferred to natural infection for many diseases (the serious ones) because vaccination gives protection without the risks incurred with infection. However, if the individual has had the infection anyway then the risks will already have been incurred – while vaccination could offer some additional protection for some diseases, this doesn’t appear to be the case with Covid. Given that the Omicron variant appears to have infected the vast majority of the population of the U.K. (certainly the majority of women of child bearing age), is there anything to be gained by cajoling the remaining minority of vaccine sceptics to take the jab? For some strange reason the UKHSA decided to not inform prospective mothers of this nuance and instead steamrollered ahead with its push for vaccination, even though questions remain about the risks of the vaccines on fertility, pregnancy and the newborn child.

One final point – in the Vaccine Surveillance Report’s section on the impact of the vaccines on pregnancy it presents data on the number of mothers who got vaccinated after their pregnancy had ended. I very much disapprove of this as it is not relevant to the question of whether vaccination affects foetal development and appears simply to be propaganda to encourage vaccination.

In my next and final post in this series I’ll discuss a part of the Vaccine Surveillance Report that caused quite a stir when it started to go against the Government’s narrative – the data on infections, hospitalisations and deaths by vaccination status.

Amanuensis is an ex-academic and senior Government scientist. He blogs at Bartram’s Folly – subscribe here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

It’s not rocket science. Just look at the countries and civilisations they come from, at how those countries are, economically and socially. Countries are made by people. There’s no such thing as magic dirt. I think most people realise this – some are more honest than others about admitting it.

Sociological equivalent of a corollary of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle in physics – The Observer is Part of the Experiment.

Except sociology doesn’t deal in fundamental particles, it deals in people, the observers are biased and the experiments are loaded.

Go figure, Home Office and Hope Not Hate.

When discussing the effect of immigration or of certain classes of immigrants on public costs and fiscal revenue the calculations seem to only consider current expenditure. I have not yet seen a publicly available analysis of capital costs, inherited infrastructure and the accompanying aspect of queueing.

“Wow – staggering stats I have just received from the Acting National Statistician.

There are 494,000 people living in the country, born outside of the UK, who are currently unemployed.

For January to March 2025, the estimated number of people who were not born in the UK and were unemployed for more than one year was 102,000.

Almost half a million unemployed foreign nationals (excluding Brits born overseas) – what are they doing here? What are they contributing? On what visa?

If you are in our country and not upholding your end of the deal, then you should go home.” Rupert Lowe

But apparently we need immigrants to do the jobs that the locals won’t…

When the benefit sucking unemployed want at least £40,000 a year to work you can understand the appeal of cheap labour but fail to understand why the government is not making work more attractive by reducing taxes and cutting benefits.

It’s the miracle of Socialism!

I wouldn’t call it ideology it is more the hope that with a suffifcient number of immigrants the local culture will be overwhelmed. This gives rise to two positive outcomes in their view. It removes the local British culture which has always been hostile to them. I remember much talk about student-bashing. It also overwhelms the health and social security and education systems – these things cannot co-exist with mass immigration. It sounds paranoid but this has been a documented strategy since the 1970s and it is still widely thought to be effective as a revolutionary tool.

Denmark has just raised the retirement age to 70 to pay for the immigrants who were meant to pay for people’s retirement.

Lets be honest work until you’re dead was the only possible outcome. Logan’s Run is like paradise compared to this. You are seeing in front of your eyes your standard of living being reduced to that of the Third World. They would argue that someone has to manage decline and that they tried to do it the most painless way possible. Maybe the masses cottoned on but it was a little too late, which is exactly what they anticipated. Ninety percent of this whole agenda is about trying to cover up and distort the shortages that are coming for purely natural cyclical reasons. Just look at the rise in rice prices which is affecting many governments right now. We are not going to be able to sustain for much longer a global population anywhere near 8 billion.

Given Starmers affinity with every other country than Britain (England) how come I did not see BBC camera shots of him cheering Zimbabwe from the members stand at Trent Bridge.