The number of people not in work in the U.K. has grown by 246,000 in the past 12 months and by 641,710 since the start of the pandemic, new official figures released this morning show. Of the increase since February 2020, 352,011 is due to an increase in the number of long-term sick. While the official unemployment rate decreased in the last quarter by 0.2 to 3.6%, this conceals a huge rise in economic inactivity classified in other ways including long-term sickness. Ross Clark takes a look at the figures in the Spectator.

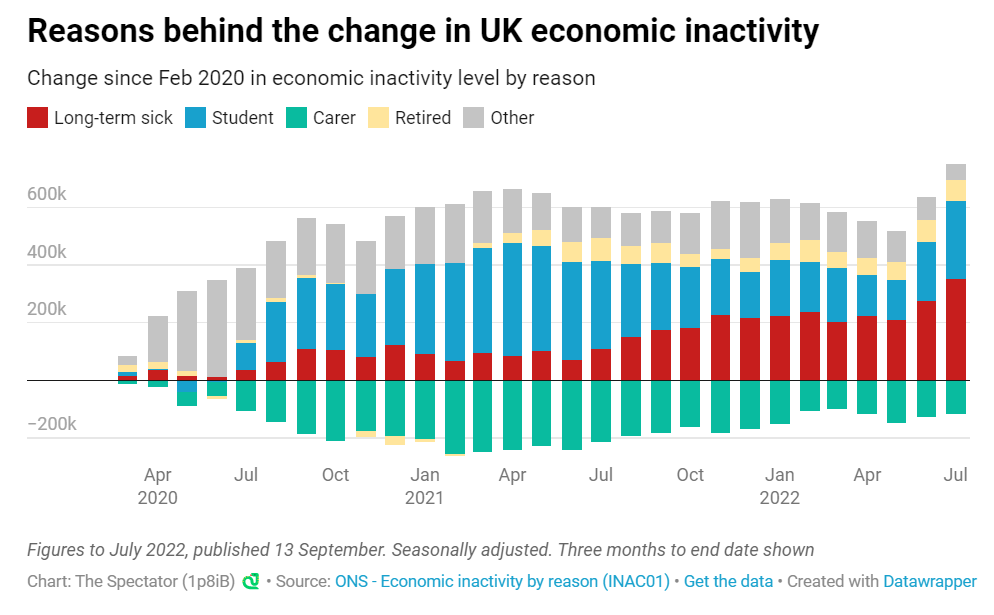

While the figure for economic inactivity includes full-time students – and the number of these has grown – further examination shows that the principal reason for the rise is an extraordinary surge in the number of people claiming long-term sickness benefits. Between May and July 2022 the number of people recorded as economically inactive was 641,710 higher than between December 2019 and February 2020. Of this rise, 270,836 was down to an increase in the number of students and 352,011 was down to an increase in the numbers of long-term sick.

Ross asks if the virus is to blame.

Is this the result of long Covid, or is it a return to the bad old days when governments used to massage unemployment figures by shunting as many people ‘onto the sick’? Today’s ONS release, sadly, can’t tell us this. But there has been a remarkable turnaround since the pandemic.

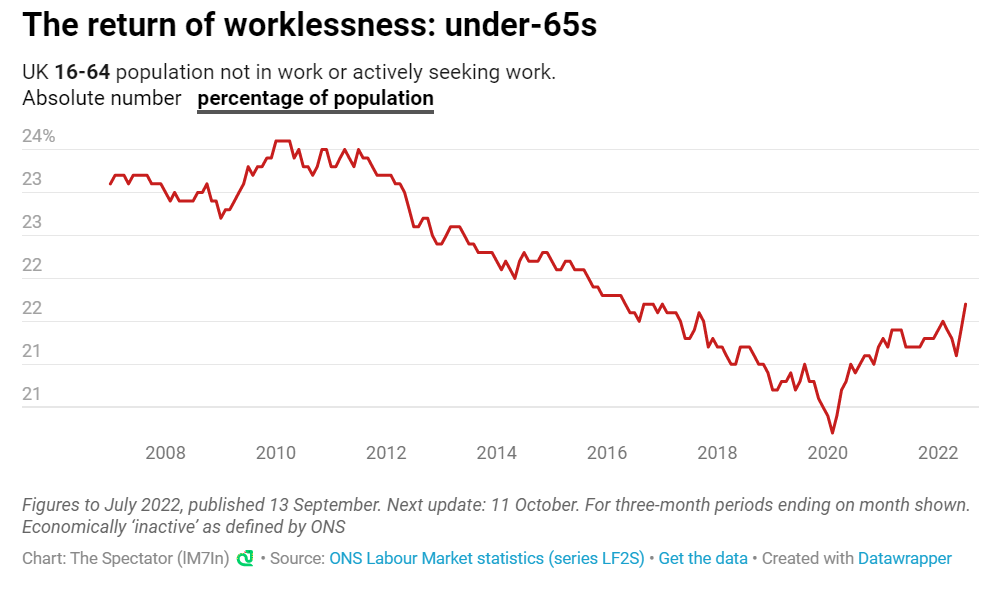

Universal Credit was specifically designed in part of tackle the problem of long-term sickness benefit. For years, people had been put on these benefits without anyone ever asking them whether they had returned to fitness or helping them back into employment. It helped reduce the unofficial unemployment figure but at the cost of keeping people unnecessarily out of work. Universal Credit sought to reverse this by obliging those on sickness benefits to prove that they were still unable to work. And for a decade it seemed to work. The economic inactivity rate fell consistently from the end of the 2008-09 recession until the beginning of 2020. Since then, however, it has started to rise again, to the point at which it is beginning to undermine the otherwise good news on employment.

There is a lot that is genuine about Britain’s low unemployment rate. A flexible labour market has made it much easier to create jobs than it is in countries which make it far harder to hire and fire staff. France’s unemployment rate, for example, is 7.4%. Much as the Labour party likes to go on about zero hour contracts and job insecurity, the reality is that if we had a labour market like that of France many of the people working in insecure jobs wouldn’t have a job at all. But Britain’s employment miracle is going to look a lot less of a miracle if everyone can see that the unemployed are being redesignated as being too sick to work.

Interestingly, most of the increase in the number of long-term sick has come since summer 2021, having declined after the second Covid wave in winter 2020-21. The big rise from July 2021 coincides with the rise in non-Covid excess deaths and the increased pressures on the health service.

Insofar as the rise in long-term sick is due to a genuine rise in people who are actually sick, it seems reasonable to assume that the same cause or causes lie behind these various indications of declining health in the population. What role are serious vaccine injuries playing in the trend? It would seem important to find out.

Ross’s piece is worth reading in full.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.