Radio 4’s Today programme had an item on Saturday 12th April 2025 (you can listen to it here; wind forward to 01:53:20) about its Book Club, specifically focusing on what it called “books for boys aged between 12 and 14” with Anthony Horowitz and Charlie Higson.

What followed could not have better illustrated the gulf between my own boyhood and the lives of boys today. One mother told the programme that her 12 year-old son liked the Wimpy Kid books (whatever they are) and she was struggling to find anything else for him that was “funny”.

I was born in 1957. By the time I was literate in the early 1960s I was reading voraciously, unsurprisingly beginning mainly with Enid Blyton and then advancing to CS Lewis, whose allegorical messages were entirely lost on me. But I soon gravitated to something much more thrilling.

All these years on I cannot remember quite when I first picked up Reach for the Sky (1954) by Paul Brickhill (1916-91). What I do know is that I could not put it down.

Reach for the Sky was the biography of Douglas Bader CBE DFC DSO (1910-82), the RAF pilot who famously lost both his legs during reckless aerobatics in 1931. Despite his relentless and ultimately successful determination that he would learn to walk again on the primitive artificial limbs of the era, he was discharged from the RAF.

But when the Second World War broke out, the frustrated Bader spotted an opportunity. With brute force of will, he succeeded in rejoining the RAF. He fought during the Battle of Britain and was shot down in August 1941, probably by friendly fire, and was incarcerated for the rest of the war. During that time Bader ended up in Colditz, the prisoner-of-war camp reserved for the most troublesome.

Today Bader is often seen in a less flattering light, not least for his air warfare strategy known as the ‘Big Wing’ and unedifying aspects of his personality. But to me aged 10 or 12, I was completely galvanized by his utterly heroic insistence on fighting back against his disability rather than turning it into a meal ticket.

Of course, the war provided Bader with a fabulous opportunity, but that only made me feel more inspired by what he and others did. I was flung into a world that every adult I knew had experienced in some form. There were still undeveloped bomb sites in London, so I knew it was all for real.

It wasn’t until many years later when at sixth form in 1976 I discovered that Pat Reid MBE MC (1910-90) had been an old boy of the school. Reid was another famous guest of the Third Reich at Colditz and had escaped. His books about Colditz had inspired the famous BBC television dramatization. He turned up at the school’s annual fête, sitting at a desk in the summer sunshine signing copies of his first book, The Colditz Story (1952), which had been republished.

I’ve still got my copy, a treasured possession, and I’ll never forget looking into the face of the man who by then was almost exactly my present age but who had led a life beyond my imagination.

There were plenty of other such books. Paul Brickhill, who I might point out was the ‘real thing’ (he had been a fighter pilot and prisoner of war himself), also produced The Great Escape (1950), another exhilarating tale of staggering heroism, resilience, and ingenuity now almost entirely known only from the movie version.

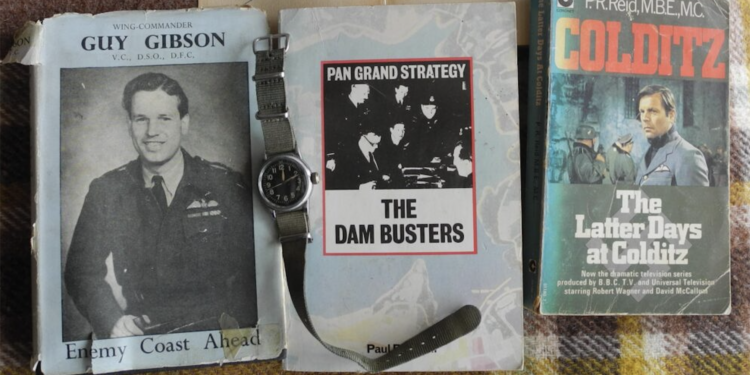

Brickhill’s The Dam Busters (1951) was no less of a thrill and introduced me to the breathtaking bravery of the boys of Bomber Command and the capabilities of the Lancaster. My mother never stopped reminding me that I shared a first name with 617 Squadron’s CO and the leader of the Dams raid of May 1943, Wing Commander Guy Gibson VC (1918-44).

Gibson’s one and only book Enemy Coast Ahead (1944) is one of the most rightly celebrated personal accounts of the air war, especially his recollection of the bouncing bomb and the dams. Gibson, as is now well known, was an elitist and in many ways an unpleasant individual. But no one could doubt his courage and skill.

The list goes on. I worked my way through Cornelius Ryan’s The Longest Day (1959) about D-Day, and his A Bridge Too Far (1974). Gratifyingly, many of these books were turned into films, evoking a strong sense of the time. CS Forester’s The Last Nine Days of the Bismarck (1959) was made into Sink the Bismarck the following year.

I saw the film aged 12 at the school film society with hundreds of other boys, all jammed into the school hall with our satchels and coats since it was shown after lessons had ended. We sat there transfixed with excitement. I watched it again only the other day and I was astonished at how well it had held up over more than 60 years.

It is wholly unimaginable that today any school would even mention Sink the Bismarck, let alone show the movie. And even if it did, there’d have to be letters to parents, advance warnings, and then counselling for the distress caused afterwards. No doubt it would have to be sandwiched between marathon viewings of Adolescence.

All we did back then in 1969 was cheer. It was incredibly exciting, but the terrible and tragic sight of HMS Hood being atomized and lost with all hands bar three when it was hit in its magazines by Bismarck will stay with me forever.

Every adult I knew in those days had experienced the Second World War, including my teachers, even if only as children. This was so everyday a fact it was easy to forget, but not on one afternoon in 1967. Our English teacher, Sammy Thurlow, looked so old and decrepit that it would have been easy to believe he was 90, at least to a boy of 10. He was in fact about 50. He shook the whole time. He was a kind man and had set us an essay on the subject of “fear”. I recall with complete clarity that he stood in front of me and said, “I hope you never know the real meaning of fear.”

It was not until later that I discovered he had been in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp and had been tortured. He of course never mentioned it.

The books I read as a boy were for real. These were real events involving real men, not the glamorised violence of Bond. The Second World War was a terrifyingly appalling time and involved some of the greatest recorded barbarities in world history, so I am not glorifying that.

What I am remembering here is that for me, at least as a boy, these books also gave me the opportunity to admire the achievements of a previous generation which, when faced with terrible adversity, stood up and faced it. We should never be ashamed of men like Bader, Gibson, and Reid, or all the others who did things we will never be called on to do ourselves.

In later life I was fortunate enough to know several men who were pilots with Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain. I made sure my four sons met those men, and they still remember the experience of doing so today.

One of them was the ace Allan Wright DFC AFC (1920-2015) of 92 (East India) SQ whom I met on a 1999 Time Team shoot to dig up one of the squadron’s Spitfires (P9373), shot down on May 23rd 1940 near Wierre-Effroy in northern France. The pilot, Sgt Paul Klipsch, had been killed. Allan, who had test-flown the Spitfire when it was new to the squadron, was an intensely modest man who refused to write up his memoirs. He told me he used to hide in the toilets at Biggin Hill in the evening, trying to recover from the trials of every day in summer and autumn of 1940 when he was fighting for his life and his country.

In an incredible development, the Spitfire’s wreckage contained maps belonging to Roger Bushell (1910-44), squadron leader of 92 SQ, who was also shot down that day. He and Klipsch must have swapped aircrafts. Bushell was the man who led the Great Escape from Stalag Luft III and was executed, along with his escape partner Bernard Scheidhauer, by the Gestapo after being recaptured. Fifty more recaptured escapees were murdered on Hitler’s orders.

And then there was my late father-in-law Adrian Carey, who was a navigator with HM Royal Navy. We still have his Bible, stained with the fuel oil that burst out when his ship, HMS Liverpool, was torpedoed off Malta by the Italians on June 14th 1942. The ship survived, and so did he – luckily for my wife, children, and grandchildren.

As a schoolboy I joined the Combined Cadet Force in 1973 and flew RAF Chipmunks. At the age of 40 I learned to fly at Biggin Hill myself. In the years following I had the enormous privilege of flying in a B-17G Fortress (in fact the very aircraft that 12 years later crashed and burned out in 2019 in Connecticut), a B-24 Liberator, and a P-51 Mustang in the United States. I did so because of the books I’d read as a kid. And my everyday watch? A US Army Air Force A-11 navigation watch from 1944. Over 80 years old and still ticking – so long as I wind it up.

As it happens, I was wearing it once in Zion National Park in Utah when an American woman recognized it as the same type as her father’s. She stopped me and told me his story of flying Liberators of the Eighth Air Force out of East Anglia.

So for me, all those better-known heroes of the war, like Bader and Gibson, stand for countless other men like Allan or my father-in-law whose stories will never be told in detail. We should all be aware of what would have happened if there hadn’t been men like them prepared to stand up and fight during those dark days. Richard Dimbleby’s celebrated and horrific account of the camp at Belsen is a graphic reminder of the impact that uncovering the horrors of the Nazi regime inflicted on those Allied forces confronted with them.

It’s quite something to look at some young men today and their disillusion, resentment, and lack of direction. Every way they turn, they are told, or it is implied, that they are deficient in some way and carry a form of original sin they cannot expiate – merely for being male. I taught in a girls’ school for nine years and, by contrast, it’s implied all the time that they are entitled to privilege and advancement, and that anything they do is worthy of admiration – merely for being female.

Yet in 1940, aged 22, Allan Wright got up every morning at the crack of dawn to hold off the Luftwaffe hordes in the Battle of Britain while his young wife tried to make a home for the couple. A few years later, Pat Reid and the other prisoners in Colditz were devising ingenious escape plans and creating maps, clothing, and equipment out of the miserable resources they had to hand. In 1944 Guy Gibson was already dead, along with hundreds of thousands of others who lost their lives in that epic conflict.

Back when I was a child, I never felt that I should apologise for being a boy and no one ever told me I ought to feel guilty about it. I’m extremely glad I have never had to fight in a war and that none of my sons have. But I’m also extremely glad I had those books to read about men whose courage and fortitude are, or ought to be, a beacon of inspiration. No work of fiction could ever compare, especially ones about ‘wimpy kids’, wizards, and juvenile James Bonds.

The world has moved on, of course, for good and ill. I doubt very much whether the Today programme’s Book Club or any school would ever recommend Reach for the Sky or The Great Escape for boys aged 12 to 14. More’s the pity.

Guy de la Bédoyère is a historian and writer with numerous books to his credit, among them several on the correspondence and writings of John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.