In an article this week highlighting side-effects resulting from the AstraZeneca Covid vaccine, BBC Health Correspondent Fergus Walsh states:

It is estimated that the Covid vaccine programme prevented over a quarter of a million hospital admissions and over 120,000 deaths in the U.K. up to September 2021.

These figures come from a UKHSA Vaccine Surveillance report published on September 30th 2021. As it happens, the UKHSA estimates were actually for England rather than the U.K. and the precise numbers were 261,500 hospitalisations averted in those aged 45 and over by September 19th 2021 and 127,500 deaths averted by September 24th 2021.

The estimates were calculated by applying vaccine effectiveness rates available at the time to known vaccination, hospitalisation and mortality data. With such models, the first question to ask is whether the results pass a basic plausibility test. Let’s see.

In the first nine months of 2021, the ONS reports about 60,000 Covid-related deaths in total. If we believe vaccination prevented 127,500 deaths, then without vaccination there would have been nearly 190,000 deaths in that period.

In the first nine months of the pandemic before vaccination (i.e., March to November 2020), the ONS also reports about 60,000 Covid-related deaths. In other words, if vaccination prevented 127,500 deaths, then without vaccination the claim is that we would have seen three times as many deaths in the nine months post-vaccination as in the nine months pre-vaccination. Given that vaccination was rolled out during a period when Covid deaths were already decreasing following the huge infection wave at the end of 2020, that is more than a stretch – it is simply implausible

Consider further that we know that a large proportion of deaths in 2021 were actually in the vaccinated (the Vaccine Surveillance Report mentioned above reveals that in September 2021, for instance, only 21% of Covid-deaths were amongst the unvaccinated) and many more occurred early in the year before people had access to vaccination. That makes the potential pool of people whose lives might have been saved by the vaccine even smaller and the estimate of 127,000 deaths averted even less credible.

The problem with the UKHSA estimates is fairly obvious. The vaccine effectiveness rates they use relate to hospitalisation or death rates for the vaccinated relative to rates for those unvaccinated and not previously infected. For this and other reasons they dramatically overestimate the effect in real world populations in which significant proportions of people have immunity from a previous infection and in which (as we now know) vaccine effectiveness wanes rapidly over time.

There is another way to test the plausibility of the estimates quoted by the BBC. In January 2023, the UKHSA produced estimates of the expected number needed to vaccination (NNV) to prevent a hospitalisation or death. These were also modelled estimates, but in contrast to the earlier approach, they used updated vaccination effectiveness rates and, crucially, took account of the fact that effectiveness waned over time.

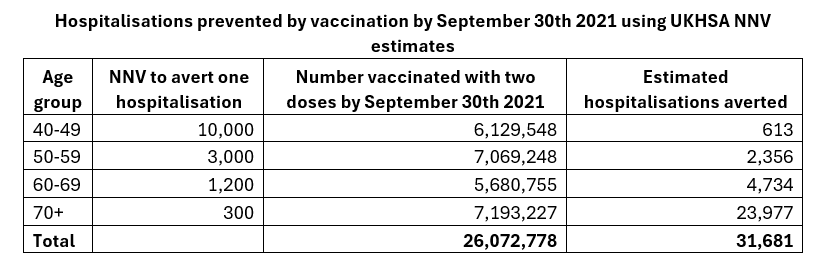

For the primary vaccination rollout, UKHSA reports NNV for hospitalisations but not for deaths (it published estimated NNV for deaths only for the booster period). I’ve taken the NNV to prevent a single hospitalisation for the primary vaccination programme and applied these figures to the total numbers vaccinated with two doses.

Note UKHSA provides separate NNV estimates for those “in a risk group” and “no risk group”, but equivalent vaccination numbers are not easy to identify for these separate categories. For this reason, I have used the reported NNV for both groups combined. I’ve also estimated hospitalisations prevented for those aged 40-plus rather than over-45s on which the 262,000 estimate was based. This is because the NNV is only reported for the whole 40-49 age group. Finally, my estimates go to the end of September, slightly longer than the period used by the UKHSA.

The NNV estimates indicate that just under 32,000 hospitalisations might have been prevented by vaccination by the end of September 2021. The (outdated) estimate reported this week by the BBC’s Fergus Walsh was eight times higher.

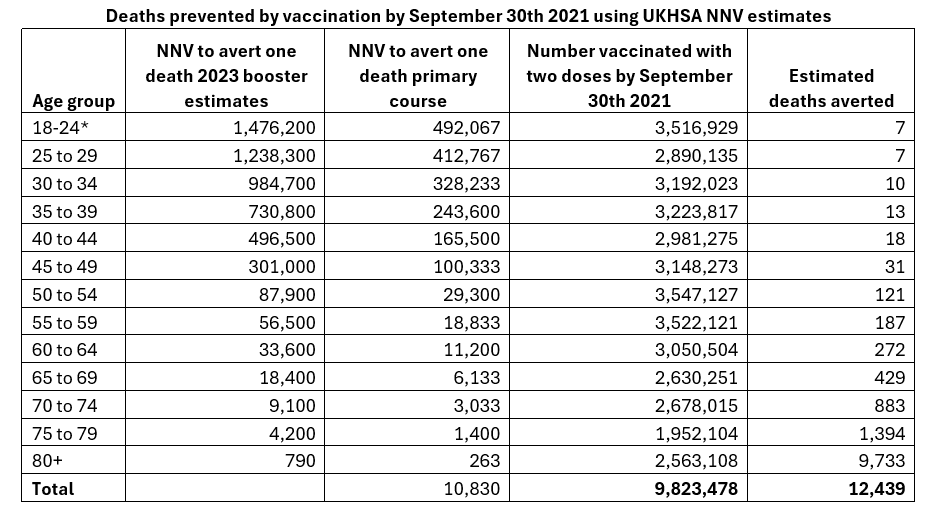

We can do a similar exercise for deaths prevented. For this we only have the NNVs reported by UKHSA for the 2023 booster programme. For hospitalisation, the NNVs are nearly three times higher in the booster period than for the primary dose (reflecting lower effectiveness of boosters). If we similarly assume the NNV to prevent one death was three times higher in the 2023 booster period, then we arrive at a figure of about 12,500 deaths prevented by the end of September 2021, just one tenth of the estimate reported by Fergus Walsh.

It is worth noting that the UKHSA still derives its NNVs from modelling and they may not reflect real-world population effectiveness. But at least the estimated numbers of hospitalisations and deaths prevented by vaccination are plausible in the context of actual data.

Presumably the BBC Health Correspondent is aware of the later UKHSA estimates of numbers needed to vaccinate. Why then is Fergus Walsh still quoting estimates of hospitalisations and deaths prevented by vaccination that are not only implausible but also way out of date?

David Paton is Professor of Industrial Economics at Nottingham University Business School. He tweets as @CricketWyvern.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“Democracy is the worst form of government………………………apart from all the rest”– Churchill. ———But ofcourse we put a cover over his statue now and a blanket over that democracy.

True varmit.. but Churchill wasn’t all that he was cracked up to be either.. he had his owners/controllers who pointed him in the

rightdirection he was required to go..Oh..look.. the Churchillians are out in force today. -6 red ones at the moment for Will L telling a few home truths about their hero. Get your heads out of your school history books and you might learn something instead of being led by the nose for the rest of your lives..

Incredible how people yearn for a saviour (past or present), isn’t it, Will?

I am a big fan of Maggie T, but I know she screwed up on several things. Just another flawed human being…

It sure is MAK.. the blind being led by the compromised and blackmailed..

Jeez.. its -14 now.. definite bullseye for Will.. ‘-)

I don’t have political hero’s mate. I gave a quote a politician (Churchill) made and you get yourself into a bit of a tizzy. So it isn’t really the case that I am pro Churchill is it? But it is certainly the case you are ANTI Churchill. ———-Bu are there any statues you wouldn’t put a blanket over? Maybe Mao or Corbyn or Stalin, or maybe Sturgeon or how about Gordon Brown or Tony (Iraq) Blair.

I’m in no tizzy and I’m not your mate.

Didn’t you note I started my post “True varmit” You obviously didn’t pick up on the nuance.

As for the rest of the unnecessary insulting tripe you’ve just thrown at me.. I’ll treat it with the contempt it deserves..

You also said the “Churchillians are out in force today”—–Indulge in your free speech if you want but don’t expect I won’t do the same “mate”. ————–I also have in my time quoted Hitler, Stalin, Thatcher Reagan, Eisenhower and a whole host of people. ——Quoting Stalin, does not make me a Stallininian.

Churchill quoting Aristotle actually.

You clearly do not understand US politics, laws, and their Constitution.

And the Conservative Party will quietly support this as their only means of survival while publicly expressing detailed concerns over timing, names and procedures.

Representative democracy only works when our elected “representatives” serve US.

That stopped with the ceaseless attempts to scupper Brexit by the House. Now Covid, and the slavish adherence of almost all MPs to the “Safe and effective” lie”, the hounding of Bridgen, coupled with the same worship of “Climate Change” shows clearly that whoever the House does represent, it is not we, the people.

Really, really DO NOT VOTE. You are voting for Davos, whoever is elected.

Yes.. Charmer Starmer even admitted he works for Davos on the BBC, and that parliament was just a talking shop. If that’s not in your face telling you how it is, I don’t know what is!

You mean you had to wait for Starmer to tell you what most of us already knew 30 years ago. —–Wakey wakey.

Democracy was always a sham, even more so when people are ‘comfortable’ and don’t feel threatened. Parliament and its occupants can pass whatever it wants with little hindrance.

I remember distinctly many years ago an old man (WW2 vet) telling me that you won’t see change until people don’t have food in their bellies. I was fifteen, he was about to retire. He also told me that by the time I was his age the country would be strangled by regulations. I thought he was just a miserable old sod.. what did he know after all..

He was right of course. Slow strangulation is the name of the game, but the pace and lies definitely quickened somewhat when Blair came to power. The slide downhill into the abyss and the populations ignorance of it go hand in hand.

Parliament should be the servant of the people, but relatively comfortable people like to be taken care of.. FATAL!

Indeed they should be, and paid by us via the Treasury. But in reality, it doesn’t look all that democratic. Back to basics via articles like this one: https://www.britannica.com/topic/democracy

In recent times, Parliament gave up and let bureaucracy go mad, and get away with it in a panic, e.g. In the modern world, we are all influenced by organisations that are not governed by “democracy” to the extent that some would like us to believe.

Good article that.. thanks for posting.

Democracy is sovereignty of the individual with no Earthly power above them, being governed by a common law, shared morals, values, manners and the interdependence of its members that specialisation and division of labour brings.

Democracy essentially is the equal distribution of power to each individual in society, so none has more than the other, none can impose his will on another.

Democracy prevents concentration of power in the hands of one or a groups to stop tyranny.

Democracy therefore prevents Government – which is the concentration of power to one or a group and therefore tyranny – from forming. The will of the majority is a tyranny of the majority which is no better than a tyranny of one.

Democratic Government is oxymoronic.

Representative Government by its nature will inevitably be corrupt and will corrupt, and bribery will be its modus operandi.

Voting your sovereignty to others to hold power over you is voting for your enslavement.

So indeed DO NOT VOTE – it makes no difference anyway.

I agree entirely.. good post..

So, the Free are always running to Freedom… and running free.

Freedom.. what’s that? Didn’t Kris Kristofferson define it once as “nothing left to lose” in his Me and Bobby McGee song..

I will give you the 20 pence version of your ramble. ———“The best government is the government that governs the least”.

The left will destroy everything because of its conviction that nobody else should be permitted to govern.,

I think you need the past instead of the future tense in that sentence.

We have never had a Parliamentary democracy, not since 1689. GK Chesterton said it best, the House of Parliament is really the House of Lords. I would say it is the House of Tyranny and now the House of Pharma-ment. So now we have the House of Faceless Bureaucracy now usurping the House of Tyranny and Pharmament. Not a surprise.

These changes will just make it easier to impose the next LD and scamdemic. The former House of Tyranny (Pharmament) can simply blame the new House of Tyranny ($cientocracy).

Sadly, the Blairite era created a European-style political class – a technocratic one that considers itself a shepherd and ordinary citizens sheep. As herd animals, we can be penned up, quarantined and forced to have any medical injections they want us to and there’s no answering back: de-banking and unpersonning is easy in response. More than anything, individual agency is to be feared. They are absolutely the sort of people Ayn Rand wrote about as threatening our freedoms. This is Frankfurt School ideology reaching the conclusion of its century-long conquest of our institutions.

Ah yes.. the Frankfurt School and their ‘critical theory’. The destroyers of anything good/joyous and proud of it..

Parliamentary sovereignty?

May I refer you to the British Constitution dated 1215 and Bill of Rights 1689.

The people are sovereign, the King isn’t, Parliament isn’t.

Seriously?

What connection do elections have to democracy, given that the Mongol Horde was exemplary in this regard? No Mongol warrior of my acquaintance has ever thought he was thus living in a ‘democracy’.

What connection does an all-powerful, unaccountable body of professional liars have to do with being democratic? They’re frontmen for the Great Nobles they replaced, freeing them from any semblance of responsibility for the peasantry.

That’s beautiful. But our parliament disappeared during the covid panic and handed all the levers of power to a bunch of technocrats and bureaucrats.

I don’t know about Gordon Brown’s constitution, but I want a constitution that enshrines my fundamental right to freedom, and nothing else.

Without it I am at the mercy of a parliament that has proven itself not just incapable of protecting my rights but prepared to trample all over them or, in the case of the WHO treaty, likely to give them away to foreign technocrats and oligarchs.

The US Bill of Rights looks pretty good to me:

The Bill of Rights: A Transcription | National Archives

I am quite prepared to sign, but I will not give my phone number, and I don’t see why it is necessary to give full address details.

I gave my address but invented a phone number.

Blair/Brown started the process with their flawed devolution settlement. And the Not-a-Conservative-Government has done what about it? Precisely nothing.

They refuse to countenance any kind of Constitutional reform, so by default leave it to Labour to mangle whenever the sheeple are stupid enough to vote them into power.

And that’s what’s going to happen again because there is absolutely no point voting for the cowards, idiots and incompetents which make up the CON Party.

There had to be a reason why the Tories were repeatedly working towards their own destruction but to be honest I could not get my head round it, this supplies the answer.

Bliar and Brown with a sprinkling of Kneel – the treasonous triumvirate.

Why does a petition need my telephone number and full address. Name , email and postcode is all that is needed. Sorry won’t sign.