Today, October 23rd, is the 1,500th anniversary of the death of the Roman statesman and writer Boethius, put to death on the orders of the Ostrogoth ruler Theodoric in AD 524. According to one tradition he had a cord twisted round his head so tightly it caused his eyeballs to protrude and was then beaten to death with a club, though the date and exact circumstances of his death are uncertain. October 23rd is the date used for commemoration by the Catholic Church for the man it knows as the Blessed Severinus Boethius.

Why is Boethius worth remembering in the Daily Sceptic?

First, because his story and that of his greatest work The Consolation of Philosophy reminds us that we share with our fellow Europeans a deep culture and long history, full of achievements of the human spirit and memories good and bad, that has nothing to do with the EU. Boethius’s life and writings and their reception are part of our common European heritage.

Second, at a time when we are constantly told that the past is full of bad things that bad people like us did to ‘the Other’, and our history is being removed daily from the walls of Nos 10 and 11 Downing Street, it is good to be reminded of someone whose writings crystallised parts of the 1,000 year old legacy of the preceding Greco-Roman civilisation and passed it on for countless numbers of people to profit from during the 1,500 years that followed.

Boethius was a Roman from a patrician family working as an official for the ‘barbarian’ Ostrogoths who had taken over control of Italy following the fall of the last Roman Emperor of the West in 476. Boethius was Catholic and Theodoric an Arian though political reasons for Theodoric’s decision to imprison and kill him seem more likely than religious ones. Born c. 480, Boethius spent his adult life as a scholarly Roman gentleman reading, thinking and writing. He was steeped in the philosophy and literature of Greece and Rome with Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Cicero and Virgil his daily intellectual companions.

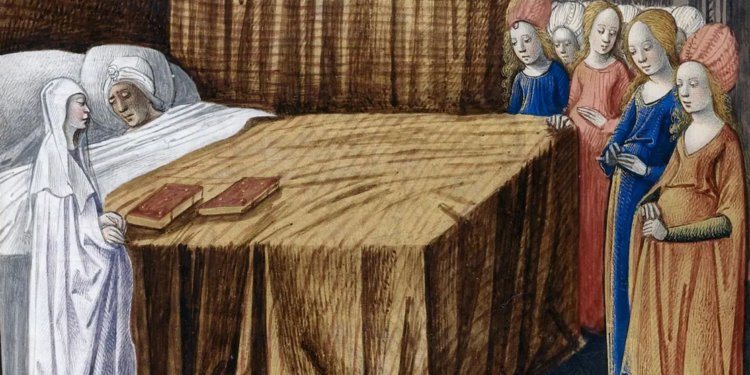

Among many writings he is chiefly remembered for The Consolation of Philosophy, which begins with the encounter in prison between Boethius and Philosophy represented by the figure of a woman. Philosophy’s role in the emerging dialogue is to console and to educate Boethius who, exiled and confined, begins with a long lament about his misfortunes. Philosophy is the doctor who tries out the remedies which might help him to put these in perspective, remind himself of the ends of the Universe, the nature of true happiness and the purpose of his life, and focus his mind on preparing his soul for death. Although Boethius was a Christian in a largely Christian society the Consolation is not a Christian book. It has been heavily Christianised in many translations but has no direct Christian references. This may be one reason for the breadth of its appeal, together with the ways it mingles verse with prose and blends in stories from history and classical mythology to make philosophical points.

The dissemination of the book throughout Europe has been extraordinary. Gilbert Highet, historian of the Western classical tradition, called Boethius “for a thousand years one of the most influential writers in Europe” and the Consolation “one of the great best-sellers”. Parchment copies of the Latin text were circulating in much of Europe throughout the Middle Ages. When printing arrived in the 15th century it quickly became one of the most published texts. There were also many translations into the vernacular. “No other book, except the Bible, was so much translated,” says Highet.

King Alfred worked on an Old English version at the end of the ninth century in the middle of his war with the Danes. Despite his authorship being in dispute the image of Alfred in his embattled Wessex kingdom communing at night with the shade of Boethius in his Pavia prison, while burning the cakes, is one that persists. Other English versions followed, the most notable being Chaucer’s in the late 14th century. The Consolation was translated into German, Provençal, Italian, Dutch, Greek and Hebrew and, above all, into French in which 12 different versions were in circulation in the late Middle Ages. There was even a 17th-century Icelandic version of one of the Consolation’s most moving poems by Stefán Ólafsson, Pastor of Vallanes in remotest north-eastern Iceland.

Educated people continued to be widely familiar with the Consolation up to the 18th century, but readership fell off in the 19th when Boethius slowly ceased to be a name one could assume others would know. The late 20th and early 21st centuries have seen an explosion of Boethian scholarship, together with the publication of David Slavitt’s excellent new translation of the Consolation, but little evidence of continuing general readership, as with so many ‘classic’ texts once widely read.

The Consolation’s readers during the preceding centuries included many women. Its most famous female reader was the now Starmer-cancelled Queen Elizabeth I, herself a former prisoner, who not only turned to it for consolation at a bad time but dictated her own English translation to her secretary during numerous sessions at Windsor in 1593 (she also translated Plutarch and Horace). Other distinguished readers who rated it highly include Samuel Johnson and Leibniz, both of whom also tried their hand at a translation, Erasmus, Robert Southey the Poet Laureate, Casanova who was made to read it when in prison, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Bertrand Russell, who called it “sublime”.

The book’s literary influence has been massive. Allusions to themes in the book can be found in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, in Dante’s Divina Commedia (where in Paradiso Boethius gets a VIP seat in The Circle of the Sun), in Boccaccio and Petrarch, and in both Milton’s Lycidas and his Comus. In the 20th-century Boethius and a copy of the Consolation play a central role in John Kennedy Toole’s Pulitzer Prize novel A Confederacy of Dunces (1980).

The Consolation is an example of ‘prison literature’, a genre to which it makes a major contribution. Boethius links his own fate with the similar ones of four of his predecessors: Cicero (murdered on the orders of Mark Anthony), Seneca (forced to kill himself by his pupil the Emperor Nero), Ovid (exiled by Augustus) and Socrates (sentenced to death by drinking hemlock). The Consolation established key features of the genre: the need to send a message to the outside world, testify for posterity, guide others and show the world that by the success of one’s struggle one has achieved the happiness which comes from the pursuit of virtue.

There was a spate of prison stories referencing Boethius in the late Middle Ages both in England and France. Two were written in London prisons by poets who were casualties of the Wars of the Roses: Thomas Usk, author of The Testament of Love, in Newgate prison from where he was sentenced in 1388 to be drawn, hanged and then beheaded, and George Ashby, who wrote Complaint of a Prisoner in the Fleet, from which prison he was lucky to be released in 1462.

In the following century it was the turn of Thomas More, imprisoned by King Henry VIII for refusing to accept the royal supremacy at the time of the Reformation. It was in the Tower of London while awaiting trial and execution in 1535 that he wrote his meditation Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation, basing it on the Consolation. Four hundred years later Dietrich Bonhoeffer, theologian and anti-Nazi dissident, in Berlin’s Tegel prison turned to More’s Dialogue for consolation in the way that More had turned to Boethius. It was one of the last things he read before he was hanged on Hitler’s orders in April 1945.

This whole story is an illustration of how the past is not “dead and silent”, as it has been called in our contemporary world, if we only make an effort to let it speak. Here we have a man (Bonhoeffer) in Germany at the end of his life in touch through a book with another man (More) in England who in a similar predicament four hundred years before was in his turn consoled by a third man (Boethius) in Italy a thousand years earlier who wrote a book drawing on the wisdom of a civilisation in Greece that had developed over 1,000 years before that (Socrates).

This long thread through a 2,500 year old history is one small example of what we mean when we say we are part of a European and Western civilisation which has remarkable elements of continuity within it. We should be proud of its achievements while remembering its cruelties and, as with our linked English and British legacies, make sure we pass on its story to the next generation.

Dr. Nicholas Tate is a former Headteacher and Government Chief Education Adviser and author of What is Education for? and The Conservative Case for Education. He was born in Stoke-on-Trent, educated at state schools and won a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Fracking ruins the countryside. Frack Off! As they say.

Not as much as poverty does. When people freeze they will take any wood to get heat. Look at a satelite picture of the dominican republic, and compare it to their neighbour.

it looks no worse than any rural industrial site, I’ve seen worse farms, this is cuadrillas lanc site

Your picture tends to support my argument. Fracking can also pollute groundwater and cause minor earth tremors.

Nonsense, it looks better than this (subsidized) biomass pellet plant

Whereas this, of course, truly enhances the landscape and operates silently and unobtrusively (in the dreams of people who want other people to suffer from them).

Right, because if you oppose fracking you must be in favour of bird choppers.

Since this is what anti-frackers regularly argue. You may be different, but then I wasn’t talking to you.

“Anti-frackers”? Oh dearie, dearie me…

No logical link between the two halves of your statement; Mumbo Jumbo is referring only to the hypocrisy of suggesting that a fracking site is an eyesore while accepting the very obvious damage done to natural vistas by wind farms. The ‘bird chopping’ aspect of these windmills is something you’ve introduced, irrelevantly.

it silently and stealthily funnels billions of pounds from people who work to people who own windy land and does nothing positive in the process

Who cares about your view? What I want is not to be cold.

Same goes for not shutting down nuclear power plants.

Windmills in the N. Sea

https://notrickszone.com/2022/02/26/messing-with-the-environment-to-fight-climate-change-wind-farms-are-altering-the-north-sea/

Photos like this don’t even begin to show the damage caused by large scale onshore wind projects. Having seen a wind farm under construction in the Highlands I regret not taking pictures, but can report that it involves building 10’s of miles of tracks as wide as a 2 lane road across sensitive peatlands and quarrying 1,000’s of tons of rock to make way for the turbine bases as well as providing a surface for the new tracks. This blasting of rock causes earthquakes (magnitude unknown, but probably as large as any caused by fracking).

Prove it, idiot. Rather than spout green nonsense.

Give us facts around how much economic damage has been done at the fracking operations at Wytch Farm since the late 70s when it was discovered?

Moonbeam .

What you gonna do – preserve a corner of a field or keep people warm? Sacrificing a bit of the countryside is sad, but necessary. Wake up!

Fracking takes place hundreds, if not thousands of metres below the water table.

Kindly explain to everyone how that can possibly affect groundwater?

Shhh. People don’t want to hear the TRUTH do they?

Have you seen what the mining of rare earths for turbines and solar panels does to the environment? And to the people mining them?

Never mind the cost

So they’re on their best behaviour when looking for permission.

Reality: they’ll take huge short term profits , then bugger off and leave the long term costs to be borne by the rest of us.

Note, ImpObs, this is the site UNDER DEVELOPMENT.

Once completed it will have the well head pad usually inside a modest shed and the perimeter of the site will be hedged and landscaped.

But it will produce more energy than square miles of wind turbines or solar subsidy farms. The energy produced will be clean and reliable and the producers (who invest their own money rather than 100% relying on taxpayer’s subsidies) will pay a huge tax rates to the exchequer.

Let Trenchy and his gormless GangGreen chums admit how much the AntiFracking campaign received and still receives from Russia. Even Hilary Clinton admitted that.

Indeed, good points.

or solar and wind farms… who take up vastly more space to generate energy far less efficiently, whilst generating huge profits for those involved, even when they are not working.

No it doesn’t. Keep your ignorance to yourself.

Bollacjs Tenchy

Have you any idea the devastation windmills and the pylons and roads cause to the pristine Scottish landscape

but razing at least 10 times the space, covering it in concrete and sticking windmills in there doesn’t?

It can certainly ruin the water table. If anyone thinks allowing a bunch of corpoate criminals to play Russian Roulette with the water table is a good idea, they need their head reading

Bollocks.

Your version of the “truth” is why old people will be dying this next winter. Instead of eating or heating their home.

Feel good, dolt?

Yes, he does, plummeting living standards is his desired goal

How does that work then? The bore holes are lined imperviously (if they weren’t the hydraulic system could never build up enough pressure to fracture the rocks) and the strata where the fracking takes place are typically 1 to 3 km below the surface, and as I suspect you know the water table is not far down else water wells wouldn’t work.

Another lie, probably watching GangGreen and ŔT too much.

Almost no potable water is extracted from deeper than 100m.

Fracking occurs significantly deeper than 1000m.

There is absolutely zero evidence of any damage to the water table and this is confirmed by the Environment Agency and the British Geological Survey.

The only Russian Roulette is GangGreen taking Russian money to enrich crony capitalists, to impoverish the poorest and most vulnerable and to destroy the economy.

No doubt you are hugging yourself already about the successes of GangGreen and Vladimir Putin.

You might want to ask yourself why the largest country in the world would mobilise against a tin pot scrap of land like the Ukraine.

Mineral or hydrocarbon resources? Not really. The threat of NATO? The Ukraine would likely never achieve membership status, quite apart from breaking agreements already in place.

But then the west is as privy to western propaganda, similar to that brought to bear during covid, as any communist state (which Russia isn’t) has ever been.

We went to war in the middle east over western government’s propaganda and lies.

Have people learned nothing?

Explain how fracking affects the water table?

How about hundreds of acres of land covered in solar panels which work considerably less than 12 hours per day. Nor has anyone invented a means by which they can be economically recycled. Instead they, like wind turbine blades which also can’t be recycled, are simply buried in landfill to leach destructive chemicals for hundreds of years.

The malicious greens moaning and bitching about nuclear waste when a Rubix cube of fissionable material is all that’s required to power an individuals entire lifetime, yet they utterly ignore the tons of material per person required by any other means to power a life.

It’s the idea of socialism on steroids; every socialist voter expects to be part of the privileged elite, come the revolution, yet it’s clear they will never achieve a position in life more than a compliant serf, assuming they evade the gulag.

“An Inconvenient Set of Truths”.

Care to comment about the dumping of raw sewage into ground level water courses? I assume you rely on bottled water ( hahaha , from where ) and a reed bed to recycle the faecal effluvia from both ends?

Or you frack off “as they say”.

Look and learn:

http://exploreshale.psu.edu/

Opposition to fracking is opposition to all energy

Apart from fracking geothermal wells, of course, where the Government and GangGreen are quite relaxed about using 7,000 times as much energy to frack as that permitted by Potato Ed Davey with his 0.5 Richter Scale limit.

No wonder he boasts about killing shale fracking. And gormless Boris won’t change it!

Point one the British Geological survey debunked the myth of major Earthquakes.

Point two as ImpOps picture below, a fracking well takes up a far smaller area of countryside than a vast Windfarm or Solar Farm.

Sorry Tenchy, you’ve fallen for the massive advertising and social media campaigns which the oil and existing energy providers have funded to wind up the emotional green mob (y’ know, those who really don’t want us to be more self-sufficient).

Never apologise for being right.

Or maybe he desires destruction for the sake of destruction. If he does desire that, what would he say differently?

You should see what lithium mines do to it…

So do wind farms and they kill the migratory birds, nit to mention the to s of concrete in the ground and the blade cemeteries needed.

You’d rather this then?

or this?

or even this?

Many of us think for ourselves. Why not have a go?

Unfortunately, thinking for yourself doesn’t necessarily return the correct answer.

I know, it’s just a few Chinese miners, and there’s loads more where they come from.

You were saying? Something about “ruining the countryside”?

Can I join in?

https://www.industryweek.com/technology-and-iiot/article/22026518/lithium-batteries-dirty-secret-manufacturing-them-leaves-massive-carbon-footprint

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2020/06/21/blood-batteries-climate-advocates-grappling-with-the-gruesome-extractive-price-of-renewable-energy/

https://stopthesethings.com/2017/08/10/wind-industrys-dirty-little-secret-turbines-to-generate-40-million-tonnes-of-toxic-waste/

https://wattsupwiththat.com/2020/09/26/wind-turbines-generate-mountains-of-waste/

https://hbr.org/2021/06/the-dark-side-of-solar-power

https://notalotofpeopleknowthat.wordpress.com/2022/01/27/local-councils-are-subsidising-ev-charging/#comment-209973

“jimlemaistre PERMALINK

February 3, 2022 4:09 pm

A Lithium-Ion battery in one Electric Car weighs about one thousand pounds, and it is about the size of a travel trunk. It contains twenty-five pounds of lithium, sixty pounds of nickel, 44 pounds of manganese, 30 pounds cobalt, 200 pounds of copper, and 400 pounds of aluminum, steel, and plastic. Inside there are 6,831 individual lithium-ion cells.

It should concern us all, that those toxic components come from mining. For instance, to manufacture each auto battery, you must process 25,000 pounds of brine for the lithium, 30,000 pounds of ore for the cobalt, 5,000 pounds of ore for the nickel, and 25,000 pounds of ore for copper. All told, you dig up 500,000 pounds of the earth’s crust for . . . just for . . . ONE . . . Electric Car Battery.

Let that one sink in, then added, “I mentioned disease and child labor a moment ago. Here’s why. Sixty-eight percent of the world’s cobalt, a significant part of a battery, comes from the Congo. Their mines have no pollution controls and they employ children who die from handling this toxic material. Should we factor in these diseased kids as part of the cost of driving an electric car ?

The embedded costs not only come in the form of energy use; they come as environmental destruction, pollution, disease, child labor, and the inability to recycled Used Batteries.

The main problem with solar arrays is the chemicals needed to process silicate into the silicon used in the panels. To make pure enough silicon requires processing it with hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, nitric acid, hydrogen fluoride, trichloroethane, and acetone. In addition, they also need gallium, arsenide, copper-indium-gallium- diselenide, and cadmium-telluride, which all are highly toxic. Silicon dust is a hazard to the workers, and furthermore the panels cannot be recycled.

Windmills are the Ultimate in embedded costs and Environmental Destruction. Each one weighs 1,688 tons (the equivalent of 23 houses) and they contain 1,300 tons of concrete, 295 tons of steel (Concrete and Steel = 15 % Global CO2) 48 tons of iron, 24 tons of fiberglass, and the hard to extract rare earths neodymium, praseodymium, and dysprosium. Each blade weighs 81,000 pounds and will last 15 to 20 years, at which time it must be replaced. We cannot recycle used blades.

There may be a place for these technologies, but you must look beyond the myth of zero emissions. I predict EVs and windmills will be abandoned once the embedded environmental costs of making and replacing them become apparent.

I am trying to do my part with these comments. ‘The Embedded Costs’ of Going Green, but who ever asks ? Thank you for your attention, have a good day, and good luck going Green.

https://www.academia.edu/49057069/Electric_Cars_Burn_31_More_Energy_than_Gas_Cars

And we are paying for this madness so that the ‘Rich’ can signal their virtue while we starve . . .

Today the UK government approved a 54% increase in Electricity pricing . . . The madness of going ‘Green’ coming home to roost . . .”

Thank God for clean renewable energy eh? Dear me, you witless ideologue

Whilst yer actual green turbines massacre wild life, cannot sustain themselves financially and require larges areas of commercial woodlands to be hacked down, shipped across the Atlantic and burnt to provide spinning back up power.

You missed the “S” off your “name”..

Rubbish.

There have been fracking sites in the UK for 50 years, one is in a wildlife site is invisible to visitors and has never caused a problem.

They don’t care if energy becomes unaffordable for the plebs, the plebs still pay their bills regardless, we have no choice.

Someone reported the other day some MP claimed £3500 (from memory) for heating their stables or some such.

They’re stark raving mad, with the confidence we’ll still pay for it, even if we vote the other lot in we still have no choice, they’re on the geeen looney bandwagon all in too

It’s no use voting for the other lot. Labour and Conservative are two cheeks of the same arse. They’ll all have us burning £50 notes to stay warm.

Yes Tom, No matter who you vote for the bloody government gets in

“They’ll all have us burning £50 notes to stay warm.”

This.

The British government could have clamped all Russian state money in the City by now. They haven’t.

The Russian state is a “sovereign borrower”. That means its debt is very valuable to its holders. Interfere with its ability to keep up its payments on that debt, and to be considered a reliable borrower, and those holders may become obliged to write off some of their assets. You all know what happens next.

The Abramovich story is also interesting. Instructions to journalists:

Money can buy anything if you are rich enough.

Here you go, Tom, hold your hands to the screen…

Thanks!

It they get their way then the Russian will provide us with life-long heating, and we will reciprocate. Unfrotunately life at that time will be measured in milliseconds at best, but the heat will become unbearable quicker.

we need to put a stop to this:

https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/17330995/mps-charge-you-3500-energy-bills-second-homes/

Our old mate ‘Honest’ Nadhim:

“Millionaire Conservative MP Nadhim Zahawi claimed for electricity bills at his stables”

“The politician, who claimed almost £6,000 in just one year for energy bills, revealed power for the mobile home and stables was linked to his house.”

https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/millionaire-conservative-mp-nadhim-zahawi-2715379

thks for that, I knew they were ripping us off, I got the two ammounts in the headlines confused

Romania has been struggling with energy prices for years. It has one of the highest energy price compared to median income. All this despite having extensive reserves of natural gas and oil. Why? Because the EU does not allow Romania to mine gas and sell it internally at low cost. They are forcing Romania to sell their own gas to their own people at European prices, despite the median income being far below the European average. But it’s ok, because Germany sold Romania its old, beat up wind turbines. And I have it from good authority that, despite the absolute massive investment in wind power, those turbines cannot be brought online because the wind is not consistent enough.

That’s the EU for you, when are people going to realise the EU is not your best friend!

Mmmmm, seem to remember a similar EU scam involving agriculture

dumpingproducts to Africa whilst maintaining high tariffs on certain African exports to the EU…?Covid and Climate the two dominant religions of our time.

I think only two MP’s voted against net zero.

Labelling Russia ‘unfriendly’ doesn’t help. The country has always wanted to be friends with us but the criminal Yanks have always made sure that it didn’t happen.

Prove it

Spot on! The more I learn the more I am appalled at the British government’s handling of this. We prove we are aptly named as being America’s poodle and the ridiculous thing about this is they despise us anyway! I’ve always thought the claim of America being our best buddy was a lie, we were useful ‘tools’ that’s all.

Peter Hitchens agrees with you :https://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-10555573/PETER-HITCHENS-West-acts-tough-Russia-just-feeble-stand-China.htm

I think the government would rather we starve or freeze to death.

“The invasion of Ukraine has thrown into dramatic relief the danger of relying on foreign, unfriendly countries for the vital energy needed to run a modern industrial state. “

Quite the contrary. The Ukraine situation is absolutely zero to do with energy dependence and everything to do with NATO expansion.

In fact, if the US had been dependent upon Russia as the Europeans are, then they would never have chosen to wage a campaign of aggression against that country and certainly would never have committed in 2008 – against the explicit warnings of Germany – to pushing NATO further east into the Ukraine and Georgia. This is the second international war that has exploded as a direct result of that policy (the previous one being in Georgia).

They might even have been adult enough to woo Russia as the natural ally against rising China that it ought to have been, instead of forcing them into each other’s arms

There are plenty of good arguments against the stupid green panic energy policies of US sphere countries, without resorting to pandering to infantile warmongering propaganda tropes. There’s more than enough of the latter around in our mainstream media at the moment. “Evil Russian baddies! Boo! Hiss!”

Yes, it’s a joke.

And nobody has become dependent on China for anything, eh?

I am not pro-Russia (nor against). I do think the US just wants to crush the life from them. China are scary, but the US are the most scary I think. Paranoid, gung-ho, trigger-happy Defenders of Democracy.

The level of hypocricy and whiter-than-white truly sickens me. All the US cares about is power, and it will associate with whoever and do whatever without hesitation.

It amused me to hear that the West is going to ban selling semiconductors to Russia. In my experience most of them emanate from the East.

Of course. Russia is a true danger to to western woke culture. They are resolutely anti-diversity, and believe in the roles for the sexes that were mainstream in the West until recently. To be clear they see separate and distinct roles for men and women and value each for different reasons.

As indeed do I. Russia is also a Christian country, something we cannot claim to be anymore.

This does not mean what some of those in the West (but I trust nobody here) used to mean by “separate and distinct roles for men and women”.

UNESCO figures for 2018 show that 41% of Russian researchers were women (compared to 29% worldwide). I use the figures from perhaps the last year when one could have a fair idea of who was classified as a woman.

I’m pretty sure they don’t use terms like “pregnant people” and “chestfeeding”. I suspect those backward people think that’s just for women.

Son went to Moscow with a vegan friend recently. The friend made a date on Tinder with a Russian girl. When she turned up at the restaurant to meet him, my son tells me she immediately lost interest in him when he started ordering vegan food. From son’s Russian girlfriend she assured him that most Russian girls see woke Britons and vegans as gay.

I have it on very good authority that the Russian people are disgusted the west is surrendering the democratic values they were deprived of for generations and fought so hard to re-establish.

so am I. It’s criminal to see liberties being handed over without a fight and those of us who want to keep them feel totally helpless.

On Putin, someone needs to put lead between his ears and fast before we’re all dead.

And instead of talking via diplomatic channels ( as JFK did for the benefit of mankind) , one party decides to point and fire offensive weapons at the population of a country who wants to join a mutual defensive organisation. You and the rest of the deluded folks here today are fast becoming the “useful idiots” of a serial murderer guilty of using bio weapons; and a murderer who cannot be voted out via “free elections” or has that escaped notice too?

“And instead of talking via diplomatic channels“

The Russians have been talking for decades, without any indication of compromise or backing off from the US.

Eventually, it appears they decided the only course left to them was to do what the US and UK did in Yugoslavia, Iraq and Libya – wage an illegal war of choice to achieve their policy goals.

Pretending there’s some kind of moral light between Russia and the US on the use of war as a tool of policy is fatuous and dishonest, in the light of direct experience in the past quarter century.

“You and the rest of the deluded folks here today are fast becoming the “useful idiots” of a serial murderer guilty of using bio weapons”

If you still believe the comical nonsense about those “bio weapon attacks” then you are every bit as gullible as the average mask-wearing lockdowner.

Did it never occur to you that you were being lied to in much the same way you were lied to over covid?

“ and a murderer who cannot be voted out via “free elections” or has that escaped notice too?”

Free elections!?

What the heck makes you think Russia is any less “democratic” than here? There hasn’t been a party worth voting for here for a decade, and setting up a party with opinions contrary to the elite Official Truth would be flat illegal.

Stunning piece of footage here:

Illuminati Council Of Foreign Relations 2015 Reveal Ukraine Plan

https://www.bitchute.com/video/4x0jpl7GCzBn/

I was thinking that those who see themselves as the rulers of the world see that part of the world as a pivotal area in terms of who is truly dominating, who is in power. If the idea that there is a deliberate collapsing of the West going on is correct – and there is plenty of evidence for this – that the kakistocracy are moving their security to the East ie Russia and China, so they are deliberately weakening the West (would you like more woke with your convid gene therapy bioweapon spiked military sir) so that this transition can take place, seizing power in Ukraine away from the West and the EU and US sphere makes sense from that perspective.

Well, thanks for introducing me to a new word, kakistocracy (government by the least suitable or competent citizens of a state, for those who like me didn’t know). How apt.

Fascinating lady on War Room today, ex American Intelligence Putin specialist, describing how Russia has been flooding Western eco pressure groups with cash.

Why?

To kill off local gas/coal/oil production.

Result?

Germany sources 40% of its gas from Russia; Italy 50%; etc, so would be relectant to exact sanctions in the event of a conflict.

She explained how Putin plays the long game.

Our leaders, inc Johnson, have been taken for fools.

https://rumble.com/vvxxrc-author-rebekah-koffler-in-studio-talks-ukraine-russia-and-putins-playbook.html

The only fool is you for forwarding the rantings of this deranged woman. Absolutely no evidence to support anything she garbled on about.

No evidence?

Even Hilary Clinton admitted the Russian money behind the Anti frack and Anti pipeline campaigns.

If you want a fool to look at, go fetch a mirror.

Hilary Clinton says blah blah. Seriously she is just another politician I wouldn’t trust as far as I could throw her and the same goes for her husband too. Its worrying you think what she says is true.

Matt Ridley has made the same observation.

Putin has benefited hugely from opposition to fracking

That’s down to the West’s corrupt green ideology, nothing to do with Russia.

I thoroughly recommend Christopher Andrew’s “Secret Service” for a run through the extent of the Russian penetration of the west from the late 1800’s onwards; bone up on Philby, Burgess, MacLean, Hollis, Blunt, Blake…

Ever heard of “The Great Game”?

Gosh, to think the Russians, needing hard foreign currency to pay for their military spending, would stoop so low as to fund green movements in countries, who sign up for their gas exports, because the rouble is not the currency of choice for suppliers of essential imports….heaven forfend.

Sounds about right to me. Let’s face it Biden’s idea of a long game is getting through the current press statement.

“Our leaders, inc Johnson, have been taken for fools.”

They haven’t done well on that score recently, have they?

German chancellor Olaf Scholz says Germany will send 1000 anti-tank weapons and 500 Stinger (anti-aircraft) missiles to Ukraine.

Germany has no border with the Ukraine. I doubt the plan is to send them by sea past Gibraltar and through the Straits of Marmara. At least one other country (looking at you, Poland) will have to allow them to transit through its airspace or across its land territory.

Will Russia allow these to arrive?

What happens when one of the Stingers brings down a Russian plane?

No Russian armoured column is on its way to Lviv as far as I am aware. That’s a situation that may change rapidly. In any case this supply of weapons may be considered a target before it even leaves Germany.

In other news, the US is denying it assisted a Ukrainian naval operation.

It has been obvious for several years now that both Jens “Loony Steinerite” Stoltenberg (NATO) and Ursula von der Leyen (former German defence minister and now president of the EU Commission) want war with Russia – they want WW3. Both of them must be in seventh heaven right now.

They are deliberately putting NATO assets in the firing line so as to trigger a NATO response. They have been plotting and planning this moment for years. This is their best chance of reducing Russia to yet another client state.

Agreed that that’s what they’re doing, but not that making Russia their client is their aim. That would require another Operation Barbarossa but successful this time. NATO-Russia war would turn nuclear within a fortnight.

The MSM in Britain are saying Russia has a lung-attacking weapon. CS gas and tear gas also attack the lungs, but the narrative now is kinda combining a view of conventional with a view of chemical and in the context of Covid also biological.

The “lab leak” hypothesis may soon morph into something very different. “How naive we were,” etc.

The US has been operating ~15 DTRA bioweapons research labs in Ukraine. This is part of a massive end run around the 1972 bioweapons resarch convention. If anything useful had been developed there, the US will have taken it to safety. It sounds like the MSM is being primed for a false flag event implicating Russia.

Seriously I pray Russia can withstand this onslaught, it sickens me the lengths the West will go to for monetary gain.

The next thing is blocking access to SWIFT and sanctioning the Russian Central Bank. Russia and China already have SWIFT alternatives, so all the sanctions will do is strengthen the alternatives.

All western countries are complicit in this war, fighting it frim the safety of their own homes without their blood being spilt.

I suspect fracking operations will create real jobs in the UK rather than mainly illusory green jobs which, in the main, only benefit the overseas manufacturers of the windmills and solar panels.

Seriously, you quote Harrabin?

This place has lost the plot.

Toby, Will, you’re fucked.

They quote himand refute his claims.

2 covid back tracking articles and a Lord Sumption one on freedom and law reform, front and centre on the Telegraph this evening, sneaking in a few reverse ferrets while everyone is distracted by the Russian squirrel. More and more are coming every day. Personally I cannot wait for the hedge funds and legal challenges to bankrupt Pfizer.

The BBC and its stooges just cannot be believed.

Gummer, who I had the misfortune to encounter over fishing matters in Suffolk, managed to find time in between his ridiculous MP expense claims, to keep the cash rolling in from his “green” business interests. A clearer conflict of interest would be difficult to find.

Yes frack if done safely, also nuclear. More will die in economic collapse but that’s the plan of some.

So if we frack for the gas to heat our miserably built, draughty, uninsulated, gas-guzzling homes, there’ll be so many earthquakes that our our miserably built … homes will fall down and be replaced with super-insulated passive houses that can be heated by a single candle and we won’t need the fracked gas …

https://www.houstonchronicle.com/business/energy/article/More-earthquakes-in-Permian-Basin-could-shake-up-16774068.php?cmpid=gsa-chron-result

https://www.houstonchronicle.com/business/energy/article/Insight-The-cost-of-dealing-with-Permian-16811840.php?cmpid=gsa-chron-result

https://www.houstonchronicle.com/opinion/editorials/article/Editorial-Permian-earthquakes-show-the-risks-of-16785983.php?cmpid=gsa-chron-result

There’s enough blood for everybody, but Vlad has the gas that the cold west so desperately needs. What if he turns it off? Will the buffoon send in the troops? I’m sure Blair would have… but then, he’s a blood-thirsty maniac.

Good to see Bob is still telling it like it is.

Gas was supplied without issue during the worst of the Cold War. If Europe orders and pays for the gas, it will be supplied, spot or long term contract as the buyer wishes. If it does not order or pay for gas deliveries, it will not be delivered.

If Europe doesn’t want to buy gas from Russia, there are other suppliers (not so cheap, but that’s the customer’s choice). Russia can readily sell gas and oil elsewhere – India has signed a rupee-deminated contract, China a massive contract (yuan ?). Currency swaps are the way it is being done. No need to buy USD for energy anymore.

And which Banks will fund the SWAPs….

It should but it won’t, the goal of Net Zero and Environmentalism is the abolition of energy.

No because the British government is corrupt, they all have their Snouts deep into the Green trough.

Green as in greenbacks?

In WW2 we fought battles in the sands of the Middle East because we and the Germans both needed oil. But we didn’t learn the lesson that we needed secure energy supplies.

In the 1970s we were held to ransom by OPEC and had serious fuel shortages.

But we didn’t learn the lesson that we needed secure energy supplies.

This island is made mainly of coal and surrounded by oil and gas fields. Only an organizing genius could produce a shortage of coal, oil and gas at the same time.

“This island is made mainly of coal and surrounded by oil and gas fields”

As a geologist who worked for years in the hydrocarbon exploiting industry, you are only correct is you are speaking from the early 1800s.

Most of the easily exploited oil gas and coal has been, as Blackadder commented “found, nicked, and spent”.

I would love it if was possible to have it all again, but you are living in the land of Boris “I’ll have my cake and eat it” Johnson.

I was paraphrasing Aneurin Bevan.

A bit of dramatic licence rather than a geology lesson.

The Afrika Korps was there to stop the Italians losing, not because the Germans thought that was the route to Middle Eastern oil.

Yes, I was being simplistic.

https://oilprice.com/Energy/Crude-Oil/How-Oil-Defeated-The-Nazis.html

Oil fields around the Caspian Sea were one of their primary targets during Operation Barbarossa. They didn’t get that far.

I’m still reeling from seeing that the term “anti-frackers” is now apparently a thing, after reading the comments here.

I really do not know if Russia is unfriendly towards us. So far I have seen no evidence of them stopping our trade or taking our money under false pretences or sending unwanted migrants across our channel. If anything I believe France is our enemy as they have always been vindictive towards us. I also think Ireland has an underlying dislike of us, not to mention Scotland. Whoops, these are the historical countries we have bailed out financially and have always had battles with……..

We have done everything we can to antagonise Russia whilst following America around like its lapdog.

We have been part of the EU for the last 40 years, or hadn’t you noticed.

If we are anyone’s lapdog it would be Germany’s.

Somewhat OT but just reading Dan Hannan’s piece in the DT about Ukraine, i was struck by his observation that Zelensky has stayed at his post in the face of Russian invaders. Compare and contrast the performance of Trudeau in the face of peaceful if angry truckers…

Nope. Zelensky ordered the distribution of ~20,000 AKs to anybody and everybody, with a couple og magazines of ammunition, then high tailed it off to Lviv into the safe loving arms of the US.

Oh, well hannan has got it wrong then!

Hannan often gets it wrong.

I heard Biden offered to get him out, but Zelensky declined.

Don’t expect our British government to do what is right for its people. If there is nothing in it for them personally, they are not interested! They don’t care about the poor or the elderly, they prefer to throw money at foreign countries, and getting us involved in wars we cannot afford.

“These renewables, however, require enormous subsidies to be viable….”

A product which requires enormous subsidies and people have to be forced to buy through coercion, punitive taxes and in due course bans on the cheaper and more efficient alternatives, ISN’T viable.

But it is incredibly lucrative for insiders.

I am against fracking for the following reasons…

If our so-called leaders had any genuine interest in the needs of the population, we would have 100% non-fossil fuel power generation, serious investment in nuclear fusion research and the creation of a public transport network that makes car ownership optional for the majority.

Fresh water isn’t pumped into the ground. It is a proprietary ‘secret sauce’ of chemicals intended to facilitate hydraulic fracturing relatively local to the injection well.

Fracking is an actual ‘pump and dump’ scheme. Based on evidence from the US, a given fracture well site has an economic lifetime of 3 – 5 years before the costs of extraction become a significant overhead. The US system is financed through ‘financial engineering’ leaving it highly susceptible to changes in gas price. The expired wells are sold on cheaply to suckers and the frackers move on to the next well site.

“It is a proprietary ‘secret sauce’”

Known as sand and a tiny fraction of lubricants.

Roughly speaking, water and sand are injected into shale causing millimetre wide cracks. The sand holds the cracks open allowing gas to filter through it.

The lubricants are for the drill bits, common in any drilling operation.

Fresh water is mixed with chemicals and sand and pumped into the ground. Something like 4 million gallons per well (which isn’t that much on the scale of things). Problem is where does all that chemical slush go afterwards?