Yesterday’s Sunday Times carried a shocking story by Christina Lamb OBE, the foreign correspondent and author.

Incredibly, not once but three times she refers to the outlawed practice of FGM (female genital mutilation) as “circumcision” of girls. That might be forgivable ignorance in a rookie male reporter, but for a writer of Lamb’s gender and experience there’s no excuse.

She reports that the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum’s is currently playing host to a group of Maasai women from East Africa in search of “sacred objects” taken from their ancestors. These include “an emonyorit – an earring worn by girls after circumcision” and “an isikira – a headdress worn by newly circumcised girls”.

The Museum’s enthusiasm for returning artefacts has been widely reported, and in the case of body parts such as shrunken heads, no-one but an idiot would oppose returning them to descendants. More controversial has been the long campaign by Pitt Rivers curator Dan Hicks to gift its superb collection of Benin bronzes to Nigeria.

As DS has reported repeatedly (here, here and here) various developments have derailed the ignorant campaign to return Benin artefacts in the last couple of years.

They were the private cult objects of a murderous line of kings, and never sacred to – or the property of – the Bini people. The greatest setback has been the Nigerian President’s shock decree that all returned Benin items would no longer belong to the Nigerian people (i.e., the National Commission for Museums and Monuments) but would be given to the current Oba of Benin, a private citizen. Similar fates have befallen other artefacts returned to Nigeria.

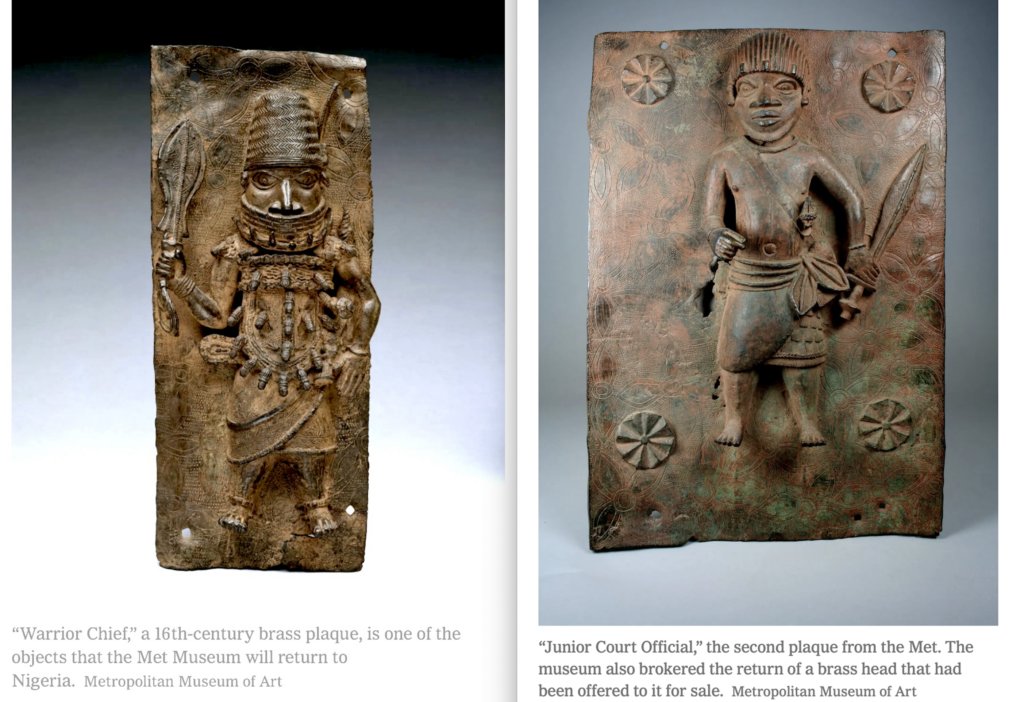

From 1991-2021, New York’s Metropolitan Museum held two Benin bronze plaques, provided by the British to Lagos Museum around 1951. After independence in 1960, they were looted by Nigerians and resurfaced in the USA. As Barnaby Phillips wrote in the second edition of his book Loot, the Met ignored his information until the first (2021) edition appeared, then caved in and returned the bronzes – not to the British, but to the Nigerians. If they were now safe in the National Commission for Museums and Monuments’ museums in Lagos or Benin, they would be recorded today on Digital Benin, but they’re not – they’ve disappeared.

The Smithsonian Museum’s National Museum of African Art suddenly lost its South African director in March 2023. She’d assured its Regents (trustees) that the RSG’s (Restitution Study Group) argument that the museum’s Benin bronzes were cast from brass bracelets used to buy slaves from the Benin kingdom was untrue. But it was true, as the Smithsonian’s own magazine was about to reveal in its archaeological report on ships wrecked on their way to West Africa. The Museum’s Director Ngaire Blakenberg had to go – and fast.

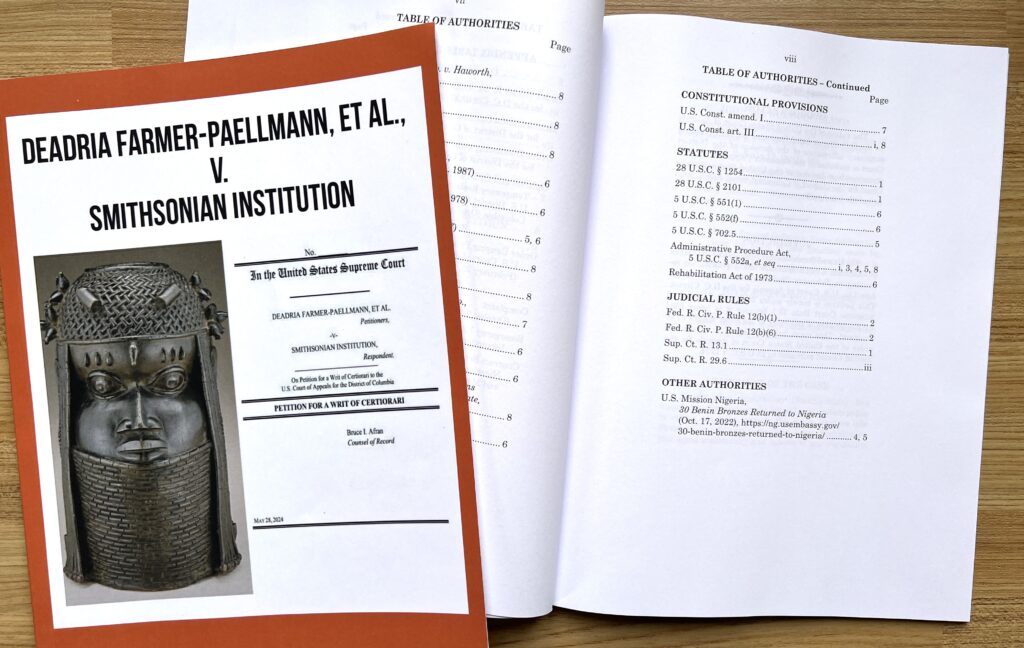

The Smithsonian secretly handed over 20 bronzes to the National Commission for Museums and Monument anyway (where are they now?) and wants to send nine more. But the RSG currently has a petition before the USA’s Supreme Court, arguing that the Smithsonian has acted unconstitutionally by setting its own restitution policy without the statutory consultation.

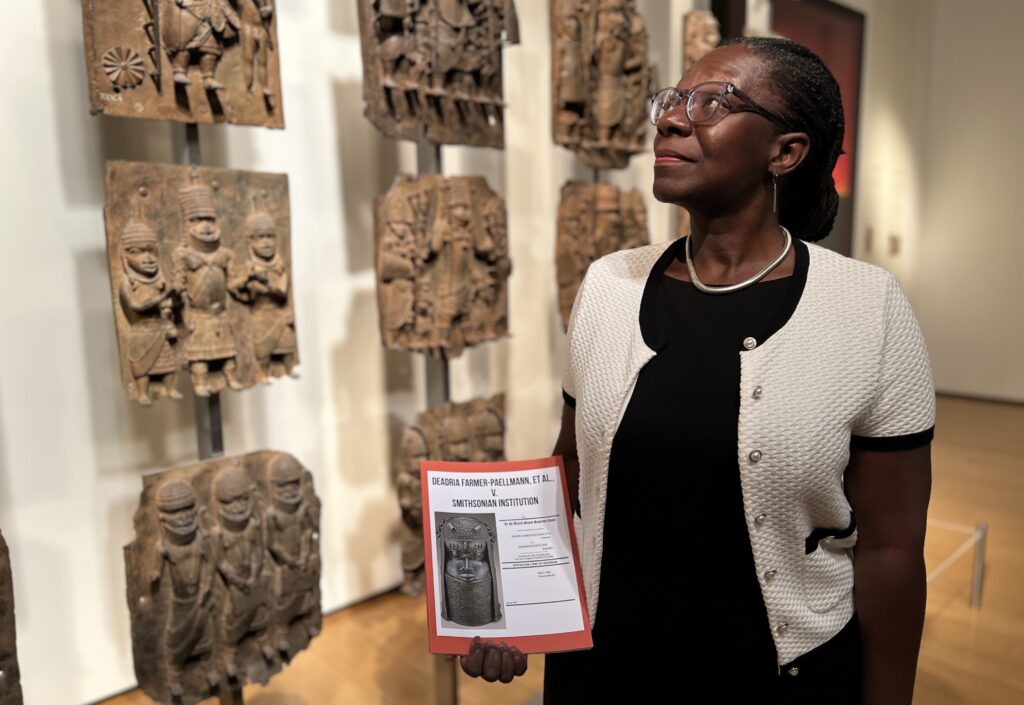

The above photo shows RSG director Deadria Farmer-Paellmann visiting the British Museum this month; she’s holding a copy of the Supreme Court petition and had been supposed to meet with a BM curator and a head of department on her visit from the USA – both were unavailable after all, one suddenly taking annual leave – to discuss the BM’s display captioning. Increasingly, museums are seeing the force of RSG’s arguments: that the brass manillas used to buy slaves and then cast the bronzes were “Blood Metal”; that the Obas of Benin were despots who enslaved other West Africans and either sold them to European traders or sacrificed them as ancestor-worship in appalling numbers.

Tens of millions of today’s Americans, Brazilians and Caribbeans are descendants of those slaves. So, says RSG, those “stolen souls” (or rather, their descendants) have a better claim on Benin artefacts than the Obas’ descendants on these “stolen goods”. The RSGs want Benin collections to remain in world museums with accurate descriptions of their origin, to honour the stolen or murdered slaves – among other things, nailing the lie that the 1897 British expedition, which finally deposed the murderous Oba and his regime, also killed thousands of his subjects.

Historically truthful descriptions would also be helpful at the Pitt Rivers Museum, as well as in articles by writers like Christina Lamb. Female genital mutilation is no longer something to be coyly referred to as “circumcision” or tolerated as ceremonial and sacred. It’s the deliberate maiming of defenceless young females, many of whom, if not killed by shock, infection or loss of blood after this torture, suffer lifelong pain. It’s still done in Africa – generally by older female relatives of the same family or tribe – and even, allegedly, in secret in the U.K., where the NHS identified nearly 12,000 victims in 2022.

Stop Press: The U.S. Supreme Court gets over 7,000 petitions a year, asking it to grant a writ of certiorari, and typically accepts only 100-150 of them for hearing. Whether the RSG’s petition against the Smithsonian Museum will be among them is due to be decided this week and presents the court with an interesting challenge to its impartiality. The Smithsonian’s Regents voted in April 2023 to hand over the museum’s Benin bronzes to Nigeria (not the Oba): these trustees include Vice President Kamala Harris and the Supreme Court’s own Chief Justice, Honorable John G Roberts Jr. – neither of whom were present for that vote, as it happens.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

All of the sceptics here were insisting the same from the day the ridiculous mask mandates were announced. It was/is obviously all just behavioural psychology.

My vote would be for a combination of safety behaviour by mysophobes and commercial interests. After all, the most common mask are nominally one-way, hence, one can sell a real lot of them when they’re mandated.

I’d be very nervous about taking medical advice from any professional who insisted on masking. If they’re ignorant enough to believe a flimsy bit of plastic tat can stop infection, what else are they wrong about?

I could not agree more CG.

As I have posted in the past there can be no greater badge of ignorance than being confronted by a so-called health care professional wearing a mask. In my opinion it undermines the industry, their “profession”, their colleagues, their understanding of medicine and science in general and it also suggests an inability to keep personal professional competence up-to-date and that is seriously worrying.

Science is for me a bit of a black hole. It bored me at school and the graphs and charts stuff presented by our former member SW left me dry – I just skipped them and waited for Kate to put them in to words. However, modern medicine is allegedly rooted in science, not that we would know it from visiting our GP surgeries and A & E clinics which these days tend to resemble a modern interpretation of voodoo churches.

“I’m a doctor me, look I’ve got a mask on. Where’s yours?”

I never, ever use them. DOCTOR!

With respect graphs and charts: it very much depends on how your mind works. For some people a graph is more informative than a 1000 words, for others they’re incomprehensible. Neither understanding more correct than the other, just different.

FL, I was not in any way criticising graphs and charts. I make it clear that when they were posted I skipped them and relied on others to provide the interpretation.

I am a lateral thinker so find the logical/ critical mode difficult. It is just the way my brain works.

Really recommend this weeks Dark Horse podcast, where they’re talking about whether we now live in a scientific Dark Age. One of the things they talk about is over-specialisation which may have made everyone stupid! Nobody is able to get an overview of any topic because everyone is so focused on their one particular specialism. May account for why we’ve seen supposed scientists support and repeat ridiculous covid nonsense and ignore the bigger picture…

Thanks CG. I will have s look.

Any chance of a link,?

This has always been the case in the scientific community. The higher your level of qualification, the narrower your field of specialisation. Taking in the bigger picture works against your climb up the greasy pole. As an individual with a low level BSc in General Science I have worked alongside so many PhD types who can hardly be trusted to buy a bag of sweets from the corner shop. Think of Ferguson as the perfect example of the species.

And I never said that you were criticising graphs and charts. Crossed wires I think.

Ok.

Actually, it very much depends on the graph itself. Just like a text, it can either be designed to be baffling and incomprehensible or simple and clear. The former is usually a sign of an (invalid) argument from authority in disguise (I understand this byzantine stuff and you don’t, therefore, you better listen to what I tell you!).

Modern medicine is rooted in Rockerfeller pharma profiteering….

I miss SW’s graphs – a bit of a geek like that 🙂

Interestingly I actually received a message from my GP yesterday that they continue to mandate Facemasks in their surgery.

Push back and ask them to provide the risk/benefit evidence – asked head nurse yesterday whilst at an appointment and it boiled down to there being no medical evidence for it only that the Trust their clinic rents space from insists on it…

Push back and ask them to provide the risk/benefit evidence

Please don’t. The nice thing about statistics is that everybody has one to prove that he’s right, regardless of what he claims to be right about. Just tell the members of the Breath is death! –faction that their paranoid delusions are pretty stale by now and ignore them. It’s up to them to avoid contact with other human beings if they’re afraid of it.

Just ignore.

The pressure to comply at these healthcare settings 😤

So many do not know there is no legal basis on which to insist on these measures – most are unaware how to push back.

The NHS Constitution allows that patients (and those supporting them e.g family member/visitor) be given information about tests and treatment options available and their risks and benefits – that includes medical interventions such as masking, testing and vaccination.

So far when asked at our appointments no information of the risks associated with testing, masking and vaccination has been provided – all hospitals, GP surgeries and dental practices have backed down and provided our treatment.

Inflation is through the roof.

The £100 tank of petrol is here, but it is entirely due to the regime pursuing ‘net zero’, lockdowns and sanctions on Russia that have backfired.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cjlqKqRRpBE

*********

David Kurten

*******

**

Stand in the Park Sundays 10.30 -11.30am

make friends & keep sane

from the globalist covid & climate propaganda

*

Wokingham

Howard Palmer Gardens Sturges Rd RG40 2HD

*

Telegram astandintheparkbracknell

These cars that cost £100 to fill the tank must have bloomin’ big tanks. I have a medium sized saloon and it costs £50 to fill it (and gives a range of about 450 miles). All the small runarounds are not going to cost anywhere near £100 to fill. If, on the other hand, you’ve got a 4×4 gas guzzler, well I’ve no sympathy. I live near a primary school and every other vehicle is a Range Rover or Discovery – god forbid the kids should have to travel in a Fiesta or similar!

Your car must have a very small tank then. I’ve had fifty cars over the years including 3 Renault clios and a Honda civic. These had “small” 42 litre tanks which at today’s prices would cost £80 to fill. My medium sized saloons had 55 litre tanks so around £100 to fill.

The hospitals seem to be removing all the mask signage but everybody still assumes they are needed. On Monday, for some blood tests, I was the only one bare faced, not even a murmur from anybody. Yesterday I was asked twice by the receptionists if I had a mask, ‘exempt, thankyou’ was accepted with a smile and one even lowered her mask when it was clear I couldn’t hear her. I think they realise they are not now required but still going through the motions regardless.

Insofar Xisident Pres and his associated organizations, eg, the WHO, are concerned, The pandemic [that never was] is far from over !!!! Practically, this means as much pandemic signalling as is feasible must be retained in the hope of better times in future, eg BIG! COVID! WAVE! IN! ISRAEL!! (fer crissake, FOAD)

“This is to keep vulnerable people as safe as possible.”

Horses arses.

Vulnerable people?? Surely they were all removed two years ago?