In a piece published last October, the left-wing journalist Aaron Bastani argued that conservatives who oppose mass immigration into Europe should also oppose Western military interventions in the Middle East. After all, Bastani reasoned, such military interventions lead to the displacement of millions of people – some of whom end up coming to Europe.

The typical conservative response to this argument is to point out that the vast majority of people coming to Europe are not in fact genuine refugees, but rather economic migrants. Indeed, many are from countries like Turkey, Morocco and Algeria where there have not been any Western military interventions in recent decades.

However, the debate has proceeded without much recourse to actual data. In this article, I attempt to redress that. Specifically, I investigate whether Western military interventions in the Middle East have contributed to mass immigration into Europe.

To do so, I analysed the UN’s International Migrant Stock database. This database gives, for each country in the world (and for several different time points), an estimate of the number of people from that country who are living in every other country around the world. One weakness is that it does not count second generation immigrants. However, this isn’t too much of an issue in the present context, since we are interested in recent immigration.

Using the database, I calculated for each of 26 Muslim countries, the number of people from that country living in the EU, Britain, Norway or Switzerland. The 26 Muslim countries are all located in the MENA region, which controls (to some extent) for one major factor affecting migration, namely distance. I did not include Muslim countries like Bangladesh, Malaysia or Indonesia in the analysis, since they are so much further away from Europe. In any case, the 26 countries are: Afghanistan, Algeria, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, UAE and Yemen.

I first calculated the migrant stock from each country for the year 2019 (the latest available). However, simply comparing migrant stocks as of 2019 isn’t a good way to test whether military interventions have contributed to mass immigration. After all, migration flows are subject to a large degree of path dependency. Once a migrant community from a particular country becomes established somewhere, more migrants from that country tend to follow. Hence we need to control for the size of the migrant stock before the interventions took place. I therefore calculated the migrant stock from each country in two earlier years: 1990, which marks the end of the Cold War, and 2000, which marks the beginning of the ‘War on Terror’. (Note that UN figures are available for 2000 but not 2001.)

However, simply looking at change in the migrant stock isn’t a good way to answer the question either. After all, some of the Muslim countries are much larger than others: Pakistan has 241 million people, whereas Brunei has only 0.5 million. Hence we also need to control for population size. I therefore divided the migrant stock from each country in each year by that country’s total population in the relevant year.

Next I identified eight countries where there have been major Western or Western-backed military interventions since 1990: Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Palestine, Somalia, Syria and Yemen. Afghanistan had the War in Afghanistan, which began in 2001. Iraq had the Gulf War in 1991 and then the Iraq War in 2003. Lebanon had the 2006 war with Israel. Libya had the NATO intervention in 2011. Palestine has the ongoing conflict with Israel. Somalia had the US intervention in 1992–95 (which was the basis for the film Black Hawk Down). Syria had the US support for rebels that began in 2011. Yemen had the US intervention that began in 2002.

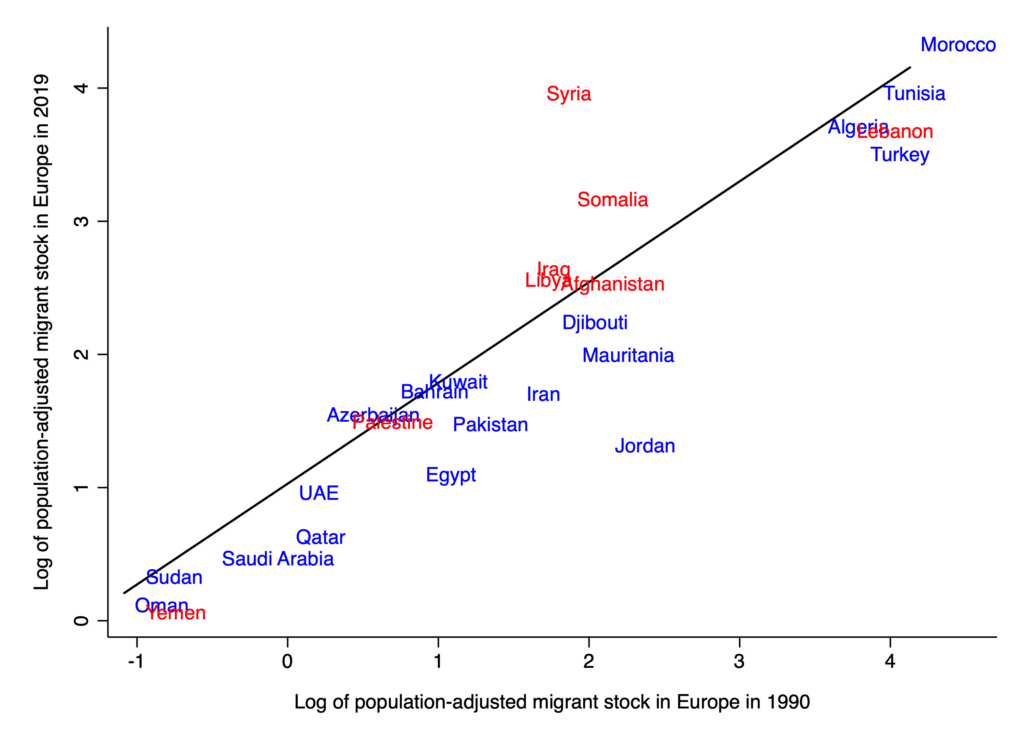

Now let’s look at some results. The chart below shows the relationship between the log of population-adjusted migrant stock in 2019 and the same variable in 1990. (Both variables were logged to reduce skewness.) The countries with Western military interventions are shown in red.

There is a strong positive relationship, indicating that between-country differences in the population-adjusted migrant stock are largely stable over time. Yet what’s also true is that most of the red countries are above the line, while most of the blue countries are below the line. This indicates that countries with Western military interventions have seen larger increases in population-adjusted migrant stocks than those without interventions. (The difference is statistically significant with a p-value of 0.006.) Indeed, when we rank the 26 countries by the residual (the vertical distance between the point and the line), six of the top seven are countries with Western military interventions.

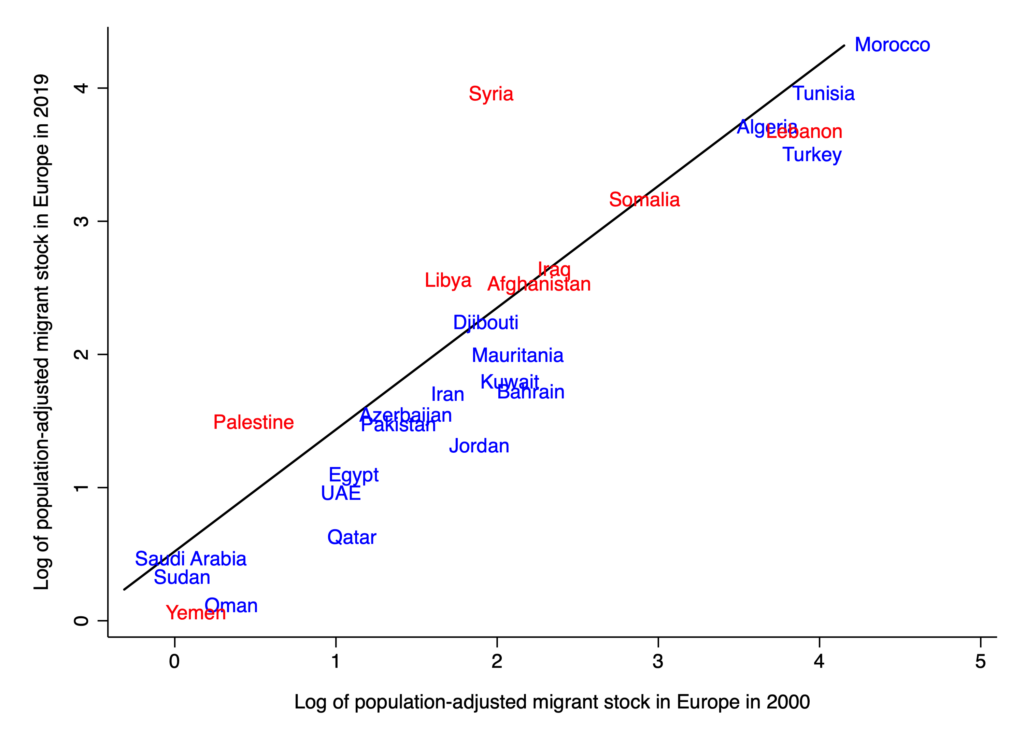

The chart below shows the same relationship when using 2000 as the baseline instead of 1990. It looks much the same as the first chart: the red countries are concentrated at or above the line, while the blue countries are concentrated below the line. Again, the difference is statistically significant with a p-value of 0.003. When we rank countries by the residual, all five of the top five are countries with Western military interventions.

(A simpler way to analyse the data is to subtract the population-adjusted migrant stock in the baseline year from the equivalent value in 2019, and then compare the two groups of countries. This method yielded similar results.)

Overall, these results support Bastani’s claim that Western military interventions in Muslim countries contribute to mass immigration. However, there are some important caveats. First, there are often many ways to analyse the data. I chose to analyse a limited sample of similar countries and did not control for factors aside from those mentioned. An alternative analysis might yield different results.

Second, in several cases it is plausible that there would still have been large-scale immigration from the relevant country in the absence of Western military intervention. For example, the civil war in Somalia during the 1990s might have produced just as many displaced people if the US had not intervened at all. Part of the difference between the two groups may be due to conflict in general, rather than Western military intervention specifically.

On the other hand, only counting migrants from MENA countries understates the impact of Western military interventions on mass immigration. In particular, the NATO bombing campaign in Libya played a major role in the defeat and eventual death of leader Muammar Gaddafi. This, in turn, led to a substantial rise in the number of Sub-Saharan migrants attempting to reach Europe through Libya. (Gaddafi had previously kept a lid on such migration in exchange for money.)

Third, even if Western military interventions do contribute to mass immigration, it remains true that most MENA migrants come from countries where there have not been such interventions in recent decades. As of 2019, only 22% of the MENA migrant stock in Europe is accounted for by migrants from countries with interventions; the three biggest groups are Algerians, Turks and Moroccans.

Given the limitations of my analysis, this article should not be taken as the final word on the subject. Nonetheless, the results are interesting.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Well surely this is a very minor consideration.

A country isn’t really a country if it cannot or will not control its borders, and this has little to do with military interventions which may be right/wrong helpful/unhelpful for reasons not really connected to the effect on immigration.

How many do we want, if any, and how should we decide who comes in? Those are the questions that need to be addressed and agreed upon. I suspect most “restrictionists” will give similar answers to those questions and will certainly be willing to answer them. Most “liberals” will not want to give direct answers.

If “the three biggest migrant groups are Algerians, Turks and Moroccan” it may well be that Western wars in nearby countries have pushed migrants into those countries which has an adverse effect on their economy and encourages some of the indigenous population of Algeria, Turkey and Morocco to seek a better life in Europe.

Those three Countries being the top three richest in the World prior?

This could apply to any of the countries that have found themselves swamped with endless incomers from cultures totally incompatible to ours. I don’t think it’s necessarily due to rose-tinted glasses that we look back over the decades to when we grew up and compare it to the absolute shambles we’re all experiencing now. Some places in the UK and elsewhere have become completely unrecognizable. I think things like increasing crime figures that correlate with increased migration from 2015 onwards is what provides the evidence. Well, that and the evidence before our very eyes, because I know where I grew up it bares no resemblance to the area now. In fact, how many places can we say, hand on heart, have changed for the better over the last decade or so? I understand change is inevitable wherever you live, and it’s futile harping on for a past you’re never going to get back, but it rarely seems to be change for the better, that’s the thing;

”Dear Great Britain,

As I reflect on the years in the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s, I can’t help but feel a deep sadness at how much you’ve changed.

There was a time when patriotism was woven into the fabric of daily life. We were quietly proud of our country, not out of obligation, but because we believed in something larger than ourselves.

The sense of community back then was palpable—neighbours were like family, and the streets were alive with familiar faces. We looked out for each other, shared stories, and found comfort in the warmth of those around us.

Now, I see empty high streets, disconnected lives, and a country that feels more divided than united.I know time brings change, but I miss the Britain where pride, community spirit, and togetherness meant everything.

The world may have moved on, but part of me still aches for the country that once was.

With fondness and sadness,

A nostalgic heart.”

https://x.com/GBPatriotUK/status/1840675710265954788

This is heartening to know, isn’t it? It really should be a case of no I.D, no entry. And even then I’d be checking the authenticity of any documents presented;

”A RECORD number of asylum seekers were caught pretending to be children in the first half of this year.

A total of 1,317 migrants claiming to be minors at the border were judged to be adults brazenly plotting to gain extra protection from being sent home.

It is the highest number for the first six months of any year on record and more than the combined totals for all of 2017, 2018 and 2019.

It is almost six times higher than the 224 rumbled by enforcement officials in all of 2014.

This year’s figure has included 283 from Afghanistan, 282 from Sudan, 236 from Vietnam and 140 from Eritrea.

A record 2,122 age disputes were launched amid fears of people- smugglers telling young adult men, often arriving without documents, to abuse the system by saying they are teen boys.”

https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/30743805/record-asylum-seekers-pretending-children/

As of 2019, only 22% of the MENA migrant stock in Europe is accounted for by migrants from countries with interventions; the three biggest migrant groups are Algerians, Turks and Moroccans.

Thank you for the time and effort to do this. Looks completely valid.

What causes mass Moslem-African

migrationinvasion?Open borders in welfare states.

Further, it is part of the Great Replacement. All planned.

Wars are used a pretext and justification but as the author calculated the vast majority of invaders are not from war zones.

And in any case, what war in France or Belgium are the cross channel invaders escaping from?

Then we have the far larger problem of the legal invasion…..it is from this that the English will be eradicated.

Wars produce refugees. Always. That’s just how it is.

https://thenewconservative.co.uk/the-mass-immigration-scam/

Here is Frank Haviland’s take on mass immigration…

“Whatever truly lurks behind the unstoppable dinghies (imported voter base, white replacement, an attempt to influence the birth rate, or the simple destruction of Britain), we are going to require an explanation – because this lie is utterly unsustainable. Until such time as the government of the day, or at the very least the ‘opposition’ A) acknowledges the issue of mass immigration honestly, B) outlines and adopts the simple solution or C) comes clean on precisely what outside interference is being exerted on them, Britain cannot be classified as a sovereign nation, leaving its people bereft of a homeland.

Being forced to fund your own destruction on the basis of a stupid lie is damning in so many ways. Not only does it make fools of us all, it makes all-out civil war inevitable. Thus far, (short-lived riots notwithstanding) the public response has in no way been commensurate with the scale of the crime committed against them. That dam will not hold forever, and even an ideologue like Starmer should have the wit to realise it.”

It’s good to see Frank writing again. The poor guy is having a torid time with his wife. Details posted on ‘the new conservative,’ blog as above.

Good luck Frank.

If the author’s thesis is accepted we should not now and never have given foreign aid to Africa. All it seems to have gone is find Marxism and put enough cas in the hands of the better connected to send their older sons to Britain.

Because wars in the Middle East haven’t been happening since God was in short trousers without Western intervention.

The reason for the influx is because Mutti big mouth extended an open invitation to all and sundry when she was Reichsfůhrer, it is EU policy to flood Europe with foreigners to destroy national identities and do away with Nationns, and because Europe has welfare systems so the goat-shaggers can live like kings.

We don’t see many of these “refugees” flocking to Pakistan, India China, South Africa – for example.

There is a pretty simple answer to Bastani’s hypothesis, specifically regarding Britain:

Nonsense!

‘The top five non-EU nationalities for long-term immigration flows into the UK in the YE December 2023 were Indian (250,000), Nigerian (141,000), Chinese (90,000), Pakistani (83,000) and Zimbabwean (36,000).’

ONS: Long-term international migration, provisional: year ending December 2023

‘Around 210,000 people had arrived in the UK under the Ukraine Family and Sponsorship Schemes by 16 July 2024.’

https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/ukrainian-migration-to-the-uk/

Thanks for reminding us that LEGAL immigration is arguably a bigger problem than ILLEGAL immigration and “refugees” and/or “asylum seekers” – this article is probably only really relevant to those latter categories.

Bastani was making a different point.

We have intervened successfully during my lifetime in Malaya, Borneo, Oman, Cyprus, The Falklands, Kuwait, Sierra Leone and, arguably, Belize.

We have intervened with less success in Afghanistan, Iraq and Libya.

I cannot see any connection between our overseas interventions, successful or otherwise, and immigration.

“I cannot see any connection between our overseas interventions, successful or otherwise, and immigration.”

I agree.

Any modern conservative minded sceptic opposes these idiotic interventions in the middle East.

What an absurd article .

Can we please drop the sillyterm military intervention and again simply call that war? Because that’s what it is: Making war on foreign countries to make them do our bidding (with more or less success), as per Clausewitz

Krieg ist die Fortsetzung der Politik mit anderen Mitteln.

[War is the continuation of [foreign] policy with different means.]

Opposing mass immigration into European countries is an issue of domestic policy which is not at all related to foreign policy issues like making war on country XYZ for some reason because this reason is never Displace lots of people which end up coming here due to an immigration policy we’re opposed to.

Insofar past wars caused mass migrations to Europe as side effect, this suggests that we should handle the fallout of such wars differently, eg, house refugees in camps close to the places they fled from – the Palestinian refugees of a number of wars in the 20th century would come to mind here – instead of in hotels in England, ie, if immigration is considered to be a problem, then, immigration policy must be changed and not foreign policy.

It’s happening because the Globalists want multi-racial/multi-cultural western societies, so they can effectively divide and rule them.

Every action, including middle eastern wars, is intended to support delivery of their overall objective: a one world government.

It’s happening because the people are coming as they know they will – by-and-large – improve their lot by doing so. Our basket-case rulers may fool themselves into believing that they’re really in control of this and that this is a convenient supply of cheap labour supplanting all the natives who aren’t born because of recruiting all women into the workforce and thus, leaving them no time to get children. But they will eventually find themselves confronted by a majority inobedient population with their own ideas for leading a life. Eg, second-line Turkish politicians talk completely openly about conquering Germany by outbreeding the ‘sickly’ native population because “our healthy women can still get children”.

The ‘Globalists’ try getting out of a hole by digging and if we don’t get rid of them first, they’ll eventually be buried by the collapsing walls of it. Under no circumstances will they achieve something US party partisans like to splash all over the internet because they believe it’ll be detrimental to the other US party.