Before it closed a few years ago, Silverlea Care Home was a residential home in the Edinburgh district of Muirhouse, overlooking Silverknowes Links and the Firth of Forth. On arriving for work one morning, volunteer carer Stuart McKenzie heard a well-worn piano playing hauntingly beautiful music. Upon investigating he found the then 73 year-old Trevor Morrison at the keys so he asked Trevor what he was playing.

Trevor told Stuart that these were tunes he had been taught when he was 10 years old, growing up on the Isle of Bute. An itinerant piano teacher would visit their home periodically and taught Trevor how to play these tunes by ear and Trevor had been playing them ever since. The teacher told Trevor that this was the music of his home, a now abandoned island community called St. Kilda. He had learned them from the old people on the islands and, to his knowledge, the songs he could still play by ear were all that remained of the music and culture of that community. Fortunately, Stuart realised the importance of this. Next shift he turned up with his PC and a newly purchased cheap microphone and he and Trevor sat down and recorded the music.

The archipelago of St. Kilda lies 70 miles west from the Scottish Mainland across the perilous North Atlantic. That distance and remoteness is compounded by the unpredictable and violent weather which even today makes voyaging there a significant challenge. Before the age of steamships the islands were essentially cut off from September to May, the anchorage lacking sufficient shelter from winter storms. Disease, economic stagnation and migration from the islands meant that by 1930 the islanders requested they be evacuated. And thus ended at least 2,000 years of human occupation: a unique indigenous island community on the edge of Europe, its songs, memories and stories scattered throughout the world and dissolved by time. Until Stuart overheard Trevor completely by accident.

After the recording, the story did the rounds, as such serendipitous stories are want to do, until it eventually reached the ear of Fiona Pope, a Decca executive. Fiona, her interest piqued, travelled to Edinburgh in 2010 to meet Trevor.

Trevor sadly passed away in 2012. But in 2016, Pope asked Sir James McMillan, Scotland’s leading conductor, to assemble contemporary Scottish musicians to record the tunes Trevor played – several of which were scored for orchestra. You can find it here.

It’s quite an album and extremely evocative, especially when you think of how these tunes, some of which will be literally thousands of years old, were nearly lost to us for ever. It’s also tragic to think that the words are now long forgotten. They would have been about love, heroes and life in such a place, as these songs are always about.

It’s been 96 years since HMS Harebell evacuated the 36 remaining St. Kildan natives from Hirta, the main island, and ended permanent human settlement. In 2016 our last remaining physical link to those people ended with the death of Rachel Johnson, who had been an eight year-old girl on that August morning as the navy’s jacks helped her and her family into the launches to take them to their new lives among the mainlanders. The story of the St. Kildans and the evacuation of the islands is fascinating and much written about and debated. How did the islanders survive in such a place? How did the islands end up being abandoned? Like everything in our history, the causes are numerous and nuanced. However, as some historians like the late Tom Steel have hinted, the arrival and impact of an extremely strict form of Presbyterianism in the 19th century caused a cultural shift which created imbalance in the economic equation necessary for feasible occupation.

The remoteness of the islands attracted clergymen who were keen to advance the physical and spiritual lives of the islanders but also demagogues and extremists who one suspects were dumped their by the authorities in Edinburgh so that they were out of the way. Both created issues. The former made the islanders increasingly reliant on outside support, the latter introduced a regime of worship that emphasised control of others over the teachings of Christ. In this there is a lesson worth exploring – that the culture of a society is intrinsically linked into everything that society does: its economic activity, its view of the world, its ethics and values, its politics. If you change that culture, you will significantly change everything else in that society and in some cases, like St. Kilda, its entire existence.

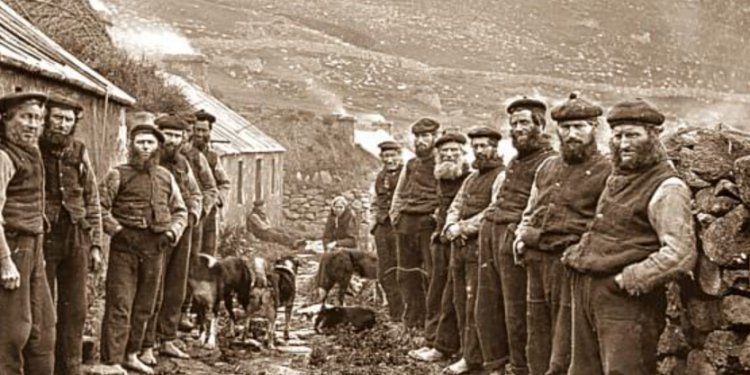

You see, by the time St. Kilda was evacuated in 1930, the population was no longer sustainable, but we need to ask why. What had changed to make the population no longer sustainable? The economy was based on a hard life of sea bird collecting, egg collecting, sheep farming and wool. The St. Kildans were the most renowned cragsmen, necessity demanding that a boy became a man when he could scale the most challenging of the archipelago’s cliffs and stacks. Equipped with huge hemp ropes, flat caps, tweed jackets and hobnailed boots or bare feet, they would scale the largest sea cliffs in the British Isles to recover eggs and young fulmar. The meat fed the islanders; the oil in their stomachs lit their homes and was exported as a valuable commodity; the feathers stuffed their mattresses. Every May, the men would row the six miles to Boray to collect gannet eggs: the stacks there are home to a third of the word’s total gannet population. The men would sheer the wild sheep which grazed on the 40 degree grassy western slopes. They would be there for two weeks and would communicate with Hirta, the main island, by turning over parts of the turf on the grassy side of the island. Depending on where the black soil was exposed would constitute the message. All too often it told home that a man had been killed, risking his life on the cliffs.

Life was hard but it was lived. Martin Martin, a Scottish Clergyman who travelled extensively around the Highlands and Islands recorded in 1697:

The inhabitants of St. Kilda, are much happier than the generality of mankind, as being almost the only people in the world who feel the sweetness of true liberty.

Tragically, such an isolated community, cut off from the Outer Hebrides, the nearest land 70 sea miles to the east, was nearly utterly destroyed by smallpox in the 1720s. As happened to other communities exposed to the ravages of that disease, the population had no immunity and only 30 islanders of nearly 180 survived. With the assistance of the Kirk and their laird, Macleod of Harris, the island population slowly grew again and the memories and crag skills that were nearly lost for ever, and which were essential to the survival on the islands, were taught to the next generation.

However, 19th century Scotland saw a schism in the Kirk (Church of Scotland) that shook Scottish communities to their core and set the islands on an irrecoverable road to dereliction. Without getting into the boggy details, the Kirk split and the two main entities that emerged were the Church of Scotland and the Free Church of Scotland. The latter being more popular in the north west and islands. It took years for this split to happen and during that time the Church on St. Kilda was closed and remained so for about 10 years. The church had been the centre of the community and the minister was also the teacher of the children. This was intolerable for some islanders and it resulted in a heavy blow when nearly 40 of them emigrated to Australia and settled as sheep farmers.

But what followed was the real blow. Christianity came late to St. Kilda, its remoteness and the difficulty of accessing the islands meant that it slipped through the Columbine mission and was pretty much ignored by the pre-Reformation Church, with a single missionary mentioning it in the 12th Century. It wasn’t until after the Reformation and well into the 1600s that Christianity became properly established. Prior to this the islanders followed a hybrid of what the old Catholic missionaries left behind and a far older indigenous faith of stones, sea and sky.

Perhaps as a result of the hardship they experienced and the constant presence of death (remarkably few St. Kildan men died in their beds – such is the life of a cragsman) they took to Christianity like a duck to water and became enthusiastic members of the Kirk. The pre-Schism, post-1600s theocracy of the 18th century Kirk was a gentle hand on the tiller and the things that make a hard life worth living – song, dancing, laughter and the odd dram – were permitted. Reverend Neil MacKenzie, who arrived on the island in 1830 and left in 1844 just as the schism bit, was clearly a man of great humanity. He introduced basic healthcare and modern crofting practices that increased productivity and yield. He was greatly missed when he retired to the mainland and the church was boarded up. MacKenzie’s departure was a serious blow for the islands, the islanders having come to rely on his leadership, wisdom and education. Without him it became apparent just how dependent on the outside they had become.

Unfortunately, by 1844 the Schism was well underway and the Church of Scotland had more pressing issues to worry about than the state of the community on Hirta, so the church remained boarded up and the school closed for over a decade. There were a few visiting ministers and schoolmasters but it wasn’t until 1865 that the island received its next permanent minister in the form of Reverend John Mackay.

MacKay was a minister in the new Free Church of Scotland and if the islanders thought they had another Mackenzie who would restore prosperity to the islands, they could not have been more wrong. Mackay was an intolerant, bigoted, bullying zealot who had the audacity to represent his joyless, choking and restrictive regime as the teachings of Christ.

Banned were dancing, singing (including the songs Trevor was taught), musical instruments, mirrors, laughter and alcohol; even tobacco was frowned upon. He introduced three services on Sunday, each often running to four hours. Children were to be seen and not heard. The Sabbath was to be so sacred that no work was permitted. All water had to be pumped on a Saturday, all food prepared then, you went to church, you went home, you sat inside the house, you didn’t even do the washing up until Monday. Children were not allowed to play, silence was observed. If a dog or a lamb went lame it had to be left until Monday, if a storm threatened the boats on the foreshore, the lifeline of the community, they had to be left to God’s will until Monday.

Worse, MacKay extended this prohibition to Saturdays. From Friday evening, no work was to take place because Friday night and Saturday were to be used in prayer preparing for the Sabbath. So strict was his rule that when an emergency supply vessel arrived on Saturday in the winter, with food and fuel and urgent medical supplies, following a storm which had wrecked much of the winter stores and had caused a famine, MacKay refused the islanders permission to unload the ship or the crew permission to unload supplies despite the perilous anchorage for the ship and the fickle and severe weather expected. It demonstrates just how much of a hold some of these ministers had over not only their congregations but the captain of the relief ship that he would rather risk his vessel and crew than upset a minister.

MacKay’s ‘reforms’ brought economic catastrophe to the islands: they simply couldn’t afford to lose a whole day out of the six working ones. The economy was too finely balanced, the calorific equation too tight. The men were under increasing pressure to provide for their families in five days, and also feed MacKay and meet the stipendiary demands of the church. MacLeod of Harris, who owned the islands, had waived his rents for most of the last 100 years, understanding the challenge, and frequently reached into his own thin pockets to help the islanders stave off starvation. But MacKay always made sure the Free Kirk got its due.

Along with MacKay’s reforms came tourists from the mainland. Steamships made the crossing considerably safer and more reliable. The tourists, frequently members of other Free Kirk congregations, landed with their Psalters and Bibles clutched in their hands. The islanders traded their tweed and folk art and their dignity for a few coins as the Victorian mainlanders gawped at them. The tourists left with their tweed shawls and left behind them influenza and, worst, neonatal tetanus, which resulted in an infant mortality rate of 80%.

No community could survive this and even during MacKay’s tenure in the 1870s there were discussions in Edinburgh and London about evacuating the islands, with increasingly desperate requests for help from MacLeod of Harris.

The St. Kildans suffered under MacKay for 24 long, miserable years. One visitor recorded a Sabbath on the islands in 1875:

The Sabbath was a day of intolerable gloom. At the clink of the bell the whole flock hurry to church with sorrowful looks and eyes bent upon the ground. It is considered sinful to look to the right or to the left.

By the time MacKay left, the islands were no longer economically viable. Entirely reliant on external help, the economic activities on which they had relied were destroyed by a man so dedicated to the pursuit of his own virtue that he couldn’t care less about the consequences, despite being challenged by others including Macleod at the time.

On that August morning in 1930, the remaining 36 islanders boarded HMS Harebell, the elderly being assisted onboard by kindly tars with the strange accents of Portsmouth, Liverpool, London and Glasgow. The sailors were instinctively aware and sensitive of the significance of this event and small acts of kindness were extended without orders. Apparently the seas on that day were calm and glassy with that ethereal light that anyone who knows the Scottish Isles will instantly recall.

The islanders’ sheep and livestock had been evacuated a few days earlier; their working dogs, who couldn’t travel to the mainland, were drowned in the bay. The cats were left behind; most starved in the first winter and the survivors were shot the next year to protect the sea birds.

The memories and songs of St. Kilda were no longer made from that day. The St. Kildans and their descendants went on to build lives across the Empire and in the United States. New ancestry tools allow them to find each other again and share the memories of their families. Few photographs of the time remain – cameras were not owned by islanders, MacKay taught they were sinful. Apart from a superb documentary recorded by the BBC in the 1970s, including interviews with the surviving islanders, little remains. Trevor’s songs of St. Kilda recall life on the island, even if only in tune. They also remind us that culture is worth fighting for and that ideological zealots who demand and force change on that culture will inevitably change it irreparably and may even destroy society entirely.

We are constantly being told how our culture doesn’t matter. Some more radical voices, several of whom are sadly occupying some of our most important academic seats across the West, go so far as to tell us that we have no culture at all and what we have was stolen from others. This cultural vandalism is now mainstream to the point that radically revisionist views of our history are being taught in our primary schools and fed to tourists at National Trusts sites. The utterly absurd recent instructions to Welsh Librarians to avoid booking venues which may have the remotest possible link to the African Slave trade is a good example of this flagellant nonsense.

It’s easy to laugh at this stuff but if you challenge it, expect to be slandered and attacked. It’s also extremely serious because a nation without a history is not a nation, for it is the history, culture, traditions and customs of a nation that provide the foundations of the nation state. Without it the nation becomes a place where people happen to live. Professor Frank Furedi explores this in his latest book The War Against the Past, why the West Must Fight for its History.

As the full tyranny of the woke religion proves itself to be every bit as intolerant, oppressive and miserable as the worst excesses of the Kirk or the Roman Church, St. Kilda is a warning about what can happen to a society if we allow the bullies to win.

C.J. Strachan is the pseudonym of a concerned Scot who worked for 30 years as a Human Resources executive in some of the U.K.’s leading organisations. Subscribe to his Substack page.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

“Also applies to those under 18”.

Those dirty child abusing bastards.

Boosters are coming soon. How will “fully vaccinated” then be defined? Will there ever be a time when everyone who wants to be is “fully vaccinated”?

Interesting measure from the well-known repressed, closet libertarian PM and his new, pragmatic, freedom-loving Health Secretary.

never had the app and I never answer calls from unknown numbers – they are normally trying to sell me something

I have an answerphone so I can monitor who phones me.

Anyone relying on this not working because of logistics is (a) missing the point and (b) dreaming.

The apparatus driving all this is not going to throw the towel in because they have a system that at this moment has some holes in it. They are going to work out how to close the loop holes, how they can close of normal life to those who are bypassing the system and eventually, if we let them, everyone will be subjected to this totalitarian nightmare.

Correct. But the first and very impirtant step is refusing to participate in their lies by sabotaging everything, see Solchenitzyn.

At the same time, we need to rev up, go to the demos etc. too.

Micro chips will be on the agenda soon.

Yep, I’ve stopped answering any unrecognised numbers.

Same here. A few years ago, I had a lot of problems with unwanted traders making nuisance calls, and my landline is a Telephone Preference Service (TPS) as well. I never answer unknown calls; most of them do not leave messages. This is sometimes useful: https://who-called.co.uk/ There seem to be quite a few users.

Me too, I always check first on http://www.tellows.co.uk if there are any negative reports. Otherwise I may call back, because you never know if it is really someone important. In most cases it is just spam 🙁

I have a landline – but no handset

Easy to get round it, just don’t download the app if you haven’t been jabbed!

Even if they did somehow tell me to isolate, won’t do it and can’t do it anyway.

If some doctator’s apparatchik asks for your internal passport you can use this.

https://hack-and-trace.me/

I’m so glad it’s back. Hopefully hosted somewhere free now…

When I said free, I meant free of interference of course…

Disgusting, discriminatory and coercive policy.

A reminder to any rational person why it is unacceptable ever to vote for the “Conservative” Party (or the Labour Party) again, bar thorough purges and genuine apologies

This announcement should be read in conjunction with the article just posted:

.As Evidence Grows That Vaccines Do Not Protect Against Infection, the Case For Granting Privileges to the Vaccinated Collapses

If there was ever a good case for a legal challenge, this is it, precisely for the reasons you state.

Even if the vaccines stopped infection it would be grotesque, but the fact that there is no proof that they do and the vaccine companies themselves admit it in their prospectuses makes the discrimination even worse.

He even admits it

And of course, anyone that tests positive will have to self-isolate whether they have had the jab or not.”

so people can still be infected after the jab, who knew?

Simple way to self-exempt from self-isolation even if you’ve refused the jab….

don’t download the App. They’ll never find you.

I can’t understand why anyone with a functioning brain has the App.

Because they love and trust

Big Brotherthe NHS, GC.Communism was only defeated after many decades. This will be a very long war.

Can also confirm that never downloaded the poxy app and never will.

A long war, ok.

The totalitarian bastards will lose.

Communism hasn’t been defeated. It just moved from east to west.

Red China are doing pretty well

Of course they might download it for you

Agree with those who say don’t download the app. If there’s some reason why you did, you can still turn its location access off on your phone. App won’t work on my old iPhone 6 anyway. But really, is there anyone here who can explain why people download the app and let it run on their phones even though they dread being pinged (and the mess it makes of your life if you are)?

Because they are infantile morons. I have not a shred of sympathy left for those people.

It’s bizarre, isn’t it? Probably a lof ot them are the same people who regularly upset their small children by testing them several times a week for a virus which won’t make them ill anyway.

i downloaded initially (with bluetooth switched off) out of the sort of curiosity you might get from seeing a train crash. looked at functionality and deleted

I even did Tim Spectors Zoe app until he came out against lockdown 3 for data reasons rather than because its fundamentally evil

I got some free lateral flow tests delivered. thought I’d test the cat or tapwater for fun. saw they were made in china. no way I’m doing that to my cat – straight in the bin

my wife came back from abroad and had to isolate for 10 days. she did isolate properly but still refused to answer the phone to the creepy spying bastards

I had 2 covid tests – one before a hospital operation, the other an LFT before being allowed into a company I was consulting for – they gave it to me and went off to make a coffee – needless to say it was negative! lol

Agreed on the Zoe disappointment.

Also, even if the app pings you telling you to self isolate, only you would know as it’s decentralised. You can just clear it’s cache (or uninstall) and the evidence is gone. Your problem will come if one of your idiot mates gets it and reports you as one of their contacts. At that point, blocking the t and t phone number will be helpful

They are Mongolians

Since no-one is fully vaccinated, then we are all the same.

Absolutely – me too ..

I love Bob

Bob Moran’s earned a lot of respect over the past 15 months.

He has been probably one of, if not the, most relevant artists in the UK this year. Top man.

We need to directly flout this and push them to take it to court. I’ve already had the virus and I’ll put my naturally acquired immunity up against the flimsy vaccine acquired immunity any day of the week.

Seriously, the time to push back and not avoid this (by not having the app or whatever) is now. Otherwise it won’t be long before they put us in camps and start asking what the Final Solution to the Unvaccinated Question is.

Never had the app. I just tell people my phone is incompatible with track/trace, and then I give false info when they want to take my details. I resent living in a communist state.

My only telephone is attached to the wall in the hall. Am I missing out?

Yes, unless you buy an extension lead…a long one. Personally, I wouldn’t bother.

Mr Old Maid and I have purchased cheap drug dealer/burner style payg mobile phones, and have invented complete backstories for our alter egos.

I suspect we have too much time on our hands …

haha I have one of those too. The burner phone I mean. I haven’t got. an alter ego yet. I’ll get to it.

Im going to be Sapphire de Winter, a glamorous divorcee with a penchant for yachts, diamonds and Russian oligarchs. Suffer from mysterious trauma that renders me unable to countenance a mask, and also unable to understand anyone wearing one. Pursued by the KGB or similar and therefore cannot leave my details for security reasons. Also allergic to PEG and multiple other vaccine ingredients. Just bring me a martini and stop with the tiresome questions.

I think I spotted you behind a pyramid of Ferrero Rocher at the Ambassador’s Reception?

Sapphire sounds v high maintenance!!

My iPhone was the first thing I got rid of at the start of this shit show, sensing that the nascent biosecurity state would require me to have one. Have been using a shitty Nokia which I absolutely hate as a piece of technology but I love taking it out and making confused face when prompted to report my whereabouts to Big Brother.

Well done to the both of you. Up to now I just give random names and numbers, but I want have a bit of fun making up pseudonyms…

Mine is Randolph de Savory, star of multiple “Mills& Boon” novels. If the Covid Marshalls see anyone kissing a leggy sloane with “passion and disdain, turning her shapely legs to jelly”, that’s me!

I have so many alter egos I have lost track of who is doing what and where!!!

Lol. A bit like a SAGE member then?

One nazi actually had the temerity to question how I spell my ‘name’. I briefly wondered whether I’d had too many aperols, and knew I wouldn’t be able to pull out the ‘real’ phone to check the spelling (the ‘burners’ being useless for getting online), so I did the only thing possible. I just laughed in her face.

I know I should have challenged her right to actually review the information, but my alter ego is a person who is completely on board with all this sh1t.

What you should know if you’ve already had Covid and considering having the jab.

https://www.greenmedinfo.com/blog/athlete-who-recovered-covid-facing-very-different-future-after-second-dose-pfizer

So basically vaccine passports-light.

And the test and trace system therefore to continue wherever we go, so not actually freedom day, more like still going to track and trace you.

And are people actually going to continue with this rubbish every time they want to enter a building?

WTF is wrong with people in this country?

Hasn’t Jabbit noticed that 67% of people testing positive for the rona in Israel were double jabbed?

The gas lighting going on right now is f u c king EPIC.

Freedom day SHOULD really mean zero restrictions thereafter i.e the way life used to be before March 2020 – not “same restrictions” but just applied in a different way. If people cannot see that that is not freedom then there is no help for us.

Speaking only for myself, and as an adult, this affects me not at all, I don’t have the app and I’ve never been tested. We are told the QR Codes used by pubs etc are going on the 19th so who else would I ever be giving my nom de plume to?

A report suggested 30% of people who have been contacted don’t fully isolate already, and that’s if they contact you at all!!

If you have to be tested for work, that’s a different matter, but outside of that it seems the only adults who are likely to be contacted are the knob-heads who set themselves up for these things? And I suspect they are very much a minority.

The worse part is obviously the under 18’s, which means school will be a fiasco,…again…and it’s perhaps a nudge towards vaccination for the under 18’s?

The battle continues….

It could be your workplace, or a club you belong to, or anywhere you’ve booked in advance and given your phone number to, or a “friend” giving your number to T&T. I’d block the number the NHS use to call you on.

“The Government will treat vaccinated and unvaccinated Brits differently on the matter of self-isolation after coming into contact with someone who has tested positive for Covid,”

But unvaccinated Brits are vanishingly unlikely to use Track and Trace so are vanishingly unlikely to be “pinged”.

I think this is just a “reward” for those who stepped forward to be vaccinated to avoid them kicking off at being treated exactly the same as the unvaccinated.

The real acid test will be about travel abroad. Will the unvaccinated be prevented from travelling in the longer term? Or have onerous conditions placed on us?

“ Will the unvaccinated be prevented from travelling in the longer term? Or have onerous conditions placed on us?”

I think we know the answer to this question don’t we?

Everyone will be prevented from travelling, but the unvaxed MORE

If the vaccine didn’t “wear off’ maybe not. But with a vaccine that needs annual boosters, for sure travel vaccine passports are here to stay.

Mrs Dent may not agree but I am happy to bide my time for a year or two to see what happens with vaccine passports for travel abroad.

That’s my plan as well. If this sheite continues into 2024, I will sell up buy a boat and bring anyone who wants off this god forsaken island a trip to whatever island of sanity still stands.

sign me up for that trip AYM please!

The more the merrier!

Sadly it’s looking that way- rather hoping one or two of the Scottish Isles will obtain sovereignty and eradicate this totalitarian insanity

Yes and me, very much enjoying all the lovely places in England to go to. Though I see it as yet more coercion of the young who would wish to travel abroad.

Within 6 months, TSWHTF for the vaccinated. Very likely, THEY will then have to be tested all the time, not us.

If I am wrong, there might at least be the Valneva, aka a proper vaccine, available for us.

Until a couple of years from now when a few million are predicted to die as result of the changes to the immune system caused by the jabs. After that, the only jabbing will hopefully be in the execution chambers of those responsible.

I think it is unworkable – largely because it is illegal, but it won’t stop other countries being difficult about letting us in and so that is where I see the biggest problem.

Not that it is going to be easy for others too: there’s a lot of vaccine diplomacy to be worked through. Who is going to recognise Sinovac? or the Indian version of AZ? or declare how long the duration of coverage for each vaccine will last? It’s ridiculously complicated for something that is basically everywhere, infecting anyone who has no immunity (and I include the vaccinated who have not had covid within that, as they are by no means immune unless it’s cross immunity from another coronavirus).

I agree. I think it will be dropped in the future as they realise the vaccines don’t stop you getting it or spreading it. they are only doing it now to increase uptake

Things will be dropped or not dropped according to how popular/unpopular they are or whether they suit wider purposes, never for sensible reasons.

Yes.

“I think this is just a “reward” for those who stepped forward to be vaccinated to avoid them kicking off at being treated exactly the same as the unvaccinated.” Exactly. As always, politics dressed as public health. They need to keep the jabbees sweet somehow.

Jeeezus. They could have gone with a lollipop and a sticker?

cheaper and appropriate for the level of critical thinking applied by the jabbees.

Anyone who uses Track and Trace needs their bumps feeling.

I saw an article about the fully vaxed being able to use separate lanes at the airport to get through quicker. How hilarious would it be if the non vaxed lane ends up quicker due to less people.

Get some boot polish and a dinghy and no travel restrictions apply

This is one of those news items that seem far more mundane than it actually is. This is absolutely huge.

If you are not vaccinated you can be placed under arbitrary house arrest, whereas if you are vaccinated you are exempted from house arrest.

That is what the rule says when you take away the euphemistic language.

A very very dark day in British history.

They gave to give the vaxxoids something in return for surrendering the last rags of their humanity.

If they drop QR. odes, how are they going to identify us humans anyway?

The legal system is not worth that label anymore.

Lol, good luck contacting me

Or me!

Does anyone who hasn’t been vaccinated participate in test and trace, I wonder?

Almost certainly not unless forced to via work, but people still may get hold of your number through various means.

No Will – I don’t have the NHS app and I’ve not been vaccinated. However, I am on the ONS study and take a PCR test once a month simply for the reason that they give me £25.00 on each occasion. Easiest money I’ve ever earned. 🙂

“Professor Chris Whitty has urged the nation to “push hell for leather” to reduce coronavirus infection rates and roll out the vaccines to prevent a significant increase in long Covid.”

“We don’t know how big an issue it’s going to be but I think we should assume it’s not going to be trivial.”

It’s going to be trivial

FFS. Has he not noticed that we have no way of controlling infection rates other than it being summer?

LOL literally 😁

“Hell for leather” Always a good approach in medicine when dealing with novel threats and treatments.

one interesting aspect

the vaccines don’t prevent you getting covid

as covid rises, people are going to be admitted to hospital ‘with’ and die ‘with’ but not ‘of’ covid and these will overwhelmingly be vaccinated people (because most are vaccinated and especially the old)

they will have to admit their numbers are bollox – only 15 months late!

But this winter’s epidemic will be a “flu” one. The vaccines cured coronavirus, remember?

So the people who die from the vaccine will actually have died with the new “flu”.

But this new flu, well we need to vaccinate EVERYONE against it. Anyone who isn’t vaccinated against the new flu is a POTENTIAL DEATHTRAP. In fact, we need a lockdown to stop the new flu. Social distancing. Masks. Track and trace. Bubbles in schools. Self-isolation. Quarantine. All to stop the spread of the deadly new flu.

They will need a new name for this deadly new flu? Covid-21?

Vaccine will become mandatory, and the Vaccine Passports will finally be upon us.

One holiday a year if you are good. Carbon credits. Social scoring. Digital currency with expiry dates.

Since they have said that vaccinations don’t stop transmissions, and they are now saying that the vaccinated can bypass rules to avoid transmissions, it can be concluded with certainty that this was never actually about transmissions, or a virus at all, but about compliance.

If it was always about compliance, then we can be certain that it was always about control.

The war for our freedoms has only just started.

Spot on. I was pointing this out today to someone who watches too much BBC. His face, as he realised it was true, was a picture.

When you don’t get jabbed, and you don’t get trapped and traced, because you avoid anywhere that insists on this LIKE THE BLOODY PLAGUE, then all this has little meaning.

Anyone know if Radacanu has been jabbed? But weird for an 18 year old to walk out of a dream scenario like that. Asking the question, not drawing conclusions

BBC have a lot to answer for there together with rest of MSM building her up massively when she is still very inexperienced. Scheduling was all wrong-she really should have been on much earlier in the day and not on Centre. It’s clear she found the occasion too much. Nothing to be ashamed of. Rated over 300 in the world and having reached the 4th round of a slam is a tremendous achievement. Mac had it dead right.

Yeah, that pressure, at that level, on a kid is likely to end in tears. Maybe she was vaxxed, but just as likely she broke under the situation.

People that age have WON Wimbledon. Not therefore a convincing argument.

I thought she was a good player – technically – and think she has great promise – but it would appear that she had a panic attack – far too much pressure on such a young kid – last British hope in the home slam etc etc etc.

I think you will find she was suffering from a condition called exhaustion.

Symptoms of fatigue

My thought precisely.

Call me Mr Picky but there are no fully vaccinated Brits

Funny my petition to opt out of the NHS (so that I’m not required to save it on the basis that it’s going to become a 2 tier service that doesn’t care about saving me) was rejected “because my claim was baseless”. I’ve kept the draft….

Please post your petition and the response!

They did offer a way to rephrase it. I could reword it, having to pay for something that I have to ‘protect’ which has been absolutely appalling to me over my life is galling.

—

Sorry, we can’t accept your petition – “Introduce an NHS opt out system for health care.”.

It included confidential, libellous, false, unproven or defamatory information, or a reference to a case where there are active legal proceedings.

We cannot publish petitions that contain false or unproven statements.

This includes unsubstantiated claims that the NHS is or plans to refuse treatment or deprioritise patients, which we have been unable to verify. We could accept a petition calling on the Government to provide a rebate to taxpayers who have private medical care, if that’s what you want to happen.

We only reject petitions that don’t meet the petition standards:

https://petition.parliament.uk/help#standards

If you want to try again, click here to start a petition:

https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/check

Thanks,

The Petitions team

UK Government and Parliament

I’ve tried to opt out of their harassment campaign but it’s seemingly impossible – they told me to contact my GP, which I did and they said they couldn’t opt anyone out of NHS England communications. Repeating the question again to NHS England has simply been ignored, as has asking three times why they consider it acceptable to leak people’s vaccination status (by using very easily identifiable bespoke blue envelopes for the harassment letters). My most recent email to them asking for details of their complaints policy was – surprise, surprise – also ignored. Next step I am looking at is a complaint to the ICO about the blue envelopes, and possibly a complaint to the police and the local MP about ongoing NHS harassment. Probably won’t get anywhere, but this organisation now clearly thinks it can do whatever it likes, and unless people stand up to its bullying it isn’t likely to change its approach.

There is no opt out at all, no right to be forgotten, nothing. I do not trust them with my confidential records and would like them expunged, no chance sadly, to be sold to the highest bidder it seems.

Keep going please. I’m up to twenty separate contacts now. It’s all very boring.

Er, no!. We are just where we were this time last year, without this jab. The odds have shifted in our favour due to the normal seasonal variations – about the only thing that seems to have remained ‘normal’ these days.

and the delta variant being about as dangerous as athlete’s foot

Not according to well renowned UFO expert Feigl-Ding..

https://twitter.com/DrEricDing/status/1412368327150874625

It’s like a grenade!

where have you been steve ?- the delta variant is deadly don’t you know? – or so MSM would have us all believe. I know LOTS of people who are VERY worried about the delta variant and who will also be very worried about the next variant which emerges.

Should we worry about the Lambda variant?Michelle Roberts

Health editor, BBC News online

if you like. I’m not but that’s because I’m not a complete c#nt

The lambda variant is perfect for the sheep

Don’t be a Lambda to the slaughter.

Be a Freeman.

No coincidence that the game focused on containment of an experiment that went wrong too…

The Lambda sensor is located in your car’s exhaust system.

or

My thanks to Wikipedia.

Lambda, like Delta, are Freemason codes too and the origins are Greek numbers. I started researching this a couple days ago to see why the government are using these codes, but typically find there’s not enough hours in the day!

Im waiting for Omega. Im sure it’ll be way more fun.

Or Sigma.

The NHS surely have the phone numbers of most who have declined the vaccination, eg husband and I were each phoned three times by someone who wanted to discuss our ‘vaccination plan’ (!). ‘Contact tracers’ don’t, as I understand it, just work via the Test and Trace – they can also contact us and say they were given the number by a ‘close contact’. And they can text as well as phone. I trust we will be informed who this ‘close contact’ is?!

No, they don’t tell you who the contact was.

I must admit I thought they didn’t…well…I’ll be keeping careful track of the people I’m in ‘close contact’ with! Do we know how ‘close contact’ is defined?

I think close proximity for 15 mins minimum.

Thanks – yes, I found something that said ‘within six feet for 15 mins minimum’.

I suppose those who downloaded the Track and Trace didn’t really care that they weren’t told who it was. After all, one 16 year-old I know who downloaded it was delighted to get ten days off school. But I will VERY much care who it is, and will want to be told.

“That’s private!”

unlike your vaccine status, obviously

What about the superior immunity conferred by recovery from this deadly disease – 99.8%.

Don’t – and I’m biased here – we deserve world class beating passports?

Caught it in Hospital where I worked – note passed tense – as a volunteer.

Won’t be allowed back unless I’m fully jabbed. So, that’s me gone.

Oh no, these days health only comes from a needle, not nature.

The infantile moronic population really believe that.

This is discrimination against those with natural immunity.

What if I was to self-identify as vaccinated does that mean I can travel again?

Roughly 80% of the population will have natural immunity (figures from Diamond Princess experiment).

….

d) An awful lot of money is being made!

“Brits”?

You mean England. Absolutely no announcements have been made about NI, Scotland or Wales regarding it.

people in NI will NEVER be free – we are on our fourth wave (apparently) and the kind of easing planned for the rest of the UK has been branded by one of our devolved ministers as “completely reckless”. While the rest of you are enjoying whatever “freedom” the government deigns to give you spare a thought for the poor people of NI who are still enslaved to these rules. Chief Medical Officer says there is “no good reason to decline the vaccination” – I could give him several he obviously isn’t aware of.

I will continue to try to be untraceable as much and as often as possible.

Never done the QR shite, never given my correct name or phone number etc. tbc.

Eff ’em.

Or do Manuel from Fawlty Towers when asked about your details:

QUE?

This is blatant medical apartheid and segregation for a man made Fauci/Gate funded virus that disappeared before March 2020. Funny nothing has been done about Fauci or Gates and the CCP Wuhan lab?

AIDS carrier’s aren’t even treated with this sort of segregation and AIDS is actully a lethal virus.

From my research the UK Gov website says that: –

Status of COVID-19

As of 19 March 2020, COVID-19 is no longer considered to be a high consequence infectious disease (HCID) in the UK.

Something very sinister is happening like this is about the Great Reset.

Mr Javid added that “of course” anyone that tested positive would have to self-isolate whether they have had the jab or not. (BBC)

Quite. And your jabbed are going to be more likely to test positive.

And more likely to engage with the whole testing theatre, so …

Lol

I don’t know about more likely, but just as likely surely, since the Great Vaxx (or indeed any vaxx for that matter) doesn’t prevent you from being exposed to the virus and potentially having moderate amounts of it in your body while your immune system is showing it the door.

That’s just it, though, A. Your immune system doesn’t show it the door at all as a result of the jab. The jab just (possibly) reduces symptoms. You’ve still got it, and you can still pass it on. The only way they can game the system so the jabbed ‘look’ clean is to reduce the cycles on their pcr tests.

Of course, I know jack about jabs or virology, or science frankly, which puts me on a similar level to most members of SAGE, it seems.

Had the nth call from out local “vaccine team” today, taken on my

voice mail (my phone only rings if the caller is on my chosen “VIP” list).

I phoned them back and said I’ve already told you many times that I decline having the jab so will you please record that and stop phoning me.

He was very apologetic and said they’ve been having problems with their recording system and that they’ve been told that a lot.

He sounded sincere but are these people being told that the jab take-up rate is way too low and therefore they need to call everyone, including those who’ve already declined?

This is *nothing* to do with the App.

The app is not legally binding and people are anonymous.

This is entirely the main track and trace system where if they go through the script you are then legally obliged to follow.

Easy to avoid by leaving fake details when asked and blocking the number (0300 013 5000)

That way if they want you they’ll have to find resources to send someone to the door (very unlikely).

** This is nothing to do with the App **

They’re not removing restrictions, they’re increasing coercion.

With PCR tests running at 45 cycles, so many compliant guinea pigs will still get a +ve result and still self isolate, despite willingly offering their arms to the state. Don’t take the “vaccines” and don’t upload the f*cking apps!

There was never any evidence that the ‘vaccine’ immunised or prevented transmission – it said that on the NHS invitation to poison yourself. Given that, why are the government propagating this apartheid narrative? It’s rhetorical.