Some years back, I was in Seoul when the Democratic People’s Republic to the north chose to attack the empty waters of the Sea of Japan with a barrage of ballistic missiles. I heard nothing of it at all in the peninsula’s southern half, and did not until concerned American friends asked if I was safe and well. Of course I was, having failed to join the squid fleets that typically plied those seas. It comes to mind in thinking about the civil unrest in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland across the past two weeks. I was present there for most of that time, and saw none of the events at hand: only British media and American correspondents alerted me to the happenings. The latter shed more heat than light — the American grasp of European affairs is generally poor, a quality amplified by orders of magnitude when discussing the European grasp on American affairs, which is simply abysmal — but the former, the putatively free press of Great Britain, illuminated a truly distressing state of affairs in a nation nearing a full century of decline.

Travelogues should be taken with due skepticism. The journalistic malpractice of going to a place to find confirmatory evidence for prior narratives is well honed. The traveler himself, as outsider, has both advantages in his dissociation from the subject, and disadvantages in that same status, not least as a transient. The marriage of objectivity and humility is uneasy. The two qualities divorce when the subject becomes a metaphor, or worse a morality tale, about oneself. In my work on Mexican and Latin American affairs I see this throughout the policy world: especially on the left, the engagement with our southern neighbors becomes first and foremost a tale of our own supposed virtues. Lifetime professionals in foreign affairs therefore extend excessive deference to narco-autocrats like the current President of Mexico, because their primary interest is not the American one, nor even the Mexican one, but the establishment of themselves as the opposites of (to them, un-virtuous) Monroe-Doctrine stalwarts.

Britain, being us — of a sort, however close and however distant — sees the phenomenon amplified. We apply the American historical-narrative template to them, and they apply it with great enthusiasm and vigor to themselves, even unto their own ruin. That ruin is everywhere you look, if you choose to look. Where we looked was very nice, the core of the state, Westminster and its regime-trainee outposts in Oxbridge. A more pleasant location could hardly be imagined, and my son, for whose benefit the expedition was undertaken, was delighted in it.

One of the conversations I’ve had over and over with Mexican, Latin American, and Spanish policymakers and intellectuals is that of why, exactly, the Hispanic world — Spain partially excepted — is perennially dysfunctional across centuries. The ideological foundation for a flourishing realm is certainly present: it would be easy to argue, for example, that the eighteenth-century Spanish Bourbons could well have set the stage for flourishing successor states in the Western Hemisphere across generations. (The Portuguese Sereníssima Casa de Bragança arguably came even closer, although their greatest prospect in Brazil was derailed by the Golpe de 1889.) But they did not. Spain itself, after two centuries of horrific passage from Napoleon to Franco, has emerged as a modern and law-governed state; the inheritors of Spain on the other hand are mostly mired in varying levels of autocratic or anarchic rule, and sometimes both. This is not the place to explore why this is at length — I’ll have an essay out as part of a larger collection on the topic later in this year — but suffice it to say that part of the answer usually arrived-at among Latin American conservatives is that the successor republics and their civics all rejected their Spanish inheritance with emphasis and finality. They are unrooted, in ways that both Aristotle and Simone Weil would have understood, and therefore unable to cohere as true nations.

This is a plausible thesis to me, and I think it is much of the answer. Much of the rest of it lies in the Latin American republics’ decision — nearly at the moment of their creation — to adopt an Anglo-American republican system to which their social mores were totally unsuited. Alexis de Tocqueville writes on this in Democracy in America: “The Mexicans were desirous of establishing a federal system, and they took the Federal Constitution of their neighbors, the Anglo-Americans, as their model, and copied it with considerable accuracy. But although they had borrowed the letter of the law, they were unable to create or to introduce the spirit and the sense which give it life.” You can see a more-detailed exploration of this enduring civic mismatch in Jorge Castañeda’s 2011 Mañana Forever, which goes in depth on how small-community mores yield very different emergent properties in Mexico and the United States. (Unremarked by Castañeda, the disturbing trend is that we are becoming more like them than they us.)

The circumstance is quite different in America’s British — or more specifically, its English — inheritance. The Americans never convulsed themselves in a general social rejection of their British heritage: even the most-radical of the Founders, a handful of Jeffersonian and adjacent thinkers, nevertheless conceived of themselves as restoring Anglo-Saxon (which is to say, pre-Norman) liberties. We care about Britain because we see it as a font, and so it is — although it is really England that is the font. We can understand American history as an extended re-litigation of the English Civil War of the mid-seventeenth century, and there is no comparable template in Scottish, and still less in Welsh or Irish, history. America is rooted in England, we feel Aristotelian philia for it — that civic friendship, united in a noble and common purpose, that is the indispensable prerequisite of nationhood — and so England becomes surpassingly important for us. We do not understand ourselves without understanding it. We also do not understand the universality underlying American propositionalism without grasping England and its achievements. I reflected upon this as I told my son, time after time, across London: this is a memorial to men who saved the world. This is Elizabeth: she defeated the Habsburg imperium. This is Drake: he turned back the Spanish at sea. This is Nelson: he confined Napoleon to Europe. This is Churchill: he waged the twilight fight against Hitler. London defied the Blitz, alone. Twice we encountered memorials related to the 1982 Falklands War, and I told him: even here a principle was at stake, and had Britain not defended it, the whole world would have suffered.

We arrogate to ourselves the idea that we are messianic because we are creations of a New World, but the truth is we get our messianism from England. Puritans voyaged from England to New England to worship their God, everyone knows that: less known is that the same men voyaged from New England to England to fight in the wars of religion against their own countrymen hardly a decade later. We are virtuous to the extent that we fulfill ideals that were only possible at the intersection of the Christian and English inheritances: faith, conscience, toleration, equality, law. We got it from nowhere else, and there is a reason that every single successor to England’s empires — or Britain’s empires — retains at minimum the forms, if not the substance, of English civics. In 1940, when Britain alone stood against the armies of darkness, the American expatriate Alice Duer Miller wrote her epic The White Cliffs, and invoked the inheritance to spur her own countrymen to action:

And were they not English, our forefathers, never more

English than when they shook the dust of her sod

From their feet for ever, angrily seeking a shore

Where in his own way a man might worship his God.

Never more English than when they dared to be

Rebels against her — that stem intractable sense

Of that which no man can stomach and still be free,

Writing: ‘When in the course of human events. . .’

Writing it out so all the world could see

Whence come the powers of all just governments.

The tree of Liberty grew and changed and spread,

But the seed was English.

Nothing remotely like this comes of the inheritors of France or Spain. There is no Algerian writer or Vietnamese intellectual yearning publicly for their French inception; there is no Mexican or Bolivian rhapsodizing about the cultural wealth left to them by Spain. I have been to the grave of the great Cortez, first among the Spanish captains, in the Mexico he singularly created, and it is neglected and deliberately obscured. The British receive a very different reception in memory. Nirad Chaudhuri’s famous — or infamous, if you are an admirer of Subhas Chandra Bose — dedication of his memoir speaks to this enduring quality upon peoples formally subjected:

To the memory of the British Empire in India,

which conferred subjecthood on us but withheld citizenship;

to which yet every one of us threw out the challenge:

‘Civis Britannicus Sum,’

because all that was good and living within us

was made, shaped and quickened by the same British rule.

Tunku Varadarajan, in his obituary for Chaudhuri, noted correctly that modern British civics would regard the late writer’s sentiments as “not merely as antediluvian but also as utterly daft.” He also described him as “the last Englishman”: a man of Bengal who gravitated toward a standard of civilization not because of his alienation from his place and people, but because of his rootedness in his own humanity. One of the tragedies of the Britain of Chaudhuri’s time was its failure to recognize that rootedness, even as it proclaimed the universal applicability of its ideals; the tragedy of Britain of our time is to regard Britain as a positive evil, with the proclamation of Civis Britannicus Sum the assertion of a madman, a slogan of the demented.

This is the truth, and the sorrow of England now is that its regime — its British regime, let us call it that, because Britain and England are not synonyms — manifestly believes that Duer Miller’s English seed was poisoned. Partly this is a consequence of the British adoption of American thoughts and narratives (they feel Aristotelian philia for us too, after all) even unto their own ruin. The effort to transplant American civic narrative on race and oppression onto English history is morally and intellectually deranging: from the American perspective, England possessed lesser virtues and lesser vices alike versus its American descendants. Partly too it is a consequence of the proximate cause of the civic violence that swept the United Kingdom across the past two weeks: its regime’s determination that the people of England be subjected and subsumed by the importation of millions of foreigners with whom no philia is possible.

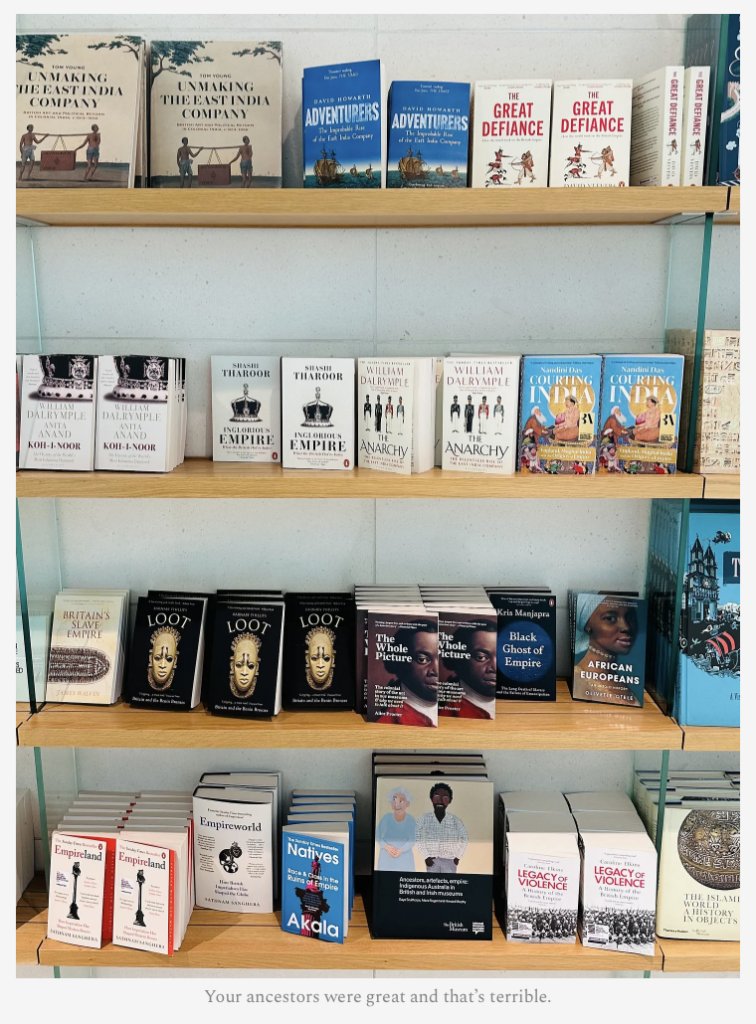

There is a regime narrative undergirding this iron fixation. You see it in the outlets for elite-approved materials at their expositions of history and its interpretations. The regime functionaries administering the British Museum, for example — arguably the single greatest museum of any kind in the world, with only Madrid’s extraordinary El Prado standing in real rivalry — make known their interpretive preferences in the capacious gift shop. There we find shelves upon shelves of books on offer detailing the evils that England has inflicted upon the world. There is Shashi Tharoor on the harm done by Britain to India. (Take that, Chaudhuri.) There is David Veevers on how the world fought Britain’s predations. There is Kris Manjapra on how British emancipation — the world’s first consequential mass emancipation in the entire history of mankind — was bad, actually. There is Barnaby Phillips with a helpful tome describing Museum holdings as “loot.” Over and over and over. The median visitor gets the message: about his country, about his ancestors, about himself. The National Maritime Museum, a comparatively unheralded but excellent expository space on British seafaring adventure and exploration — it has Nelson’s jacket with the fatal bullet hole, which spurred real emotion upon encounter — also in its shop foregrounds works by which the visitor is to understand that what he has just seen and admired is in fact deeply wrong and immoral. It is a total inversion of the scale of values and virtues to which every society across all history has adhered, and this is a regime choice.

The British Museum apparatus of commerce also, it so happens, has two sections purveying for purchase materials helpful in ushering the purchaser into the occult. As for the single most-important influence on all British history, which is to say Christianity, it has nothing in particular. This too is a regime choice. In Cambridge we visited the thousand-year old parish of St Bene’t — born the church of St Benedict — and upon the once-glorious interior there is a Reformation whitewash. The fanatics of that era meant to erase a particular faith by the erasure of its art. The fanatics of this era draw near to completing their work, and substituting its antithesis.

The end of Christian iconography in the old sites and realm of English Catholicism does not mean the end of iconography. Quite the opposite: the new religion clambers upon the ruined edifice of the old and apes its forms. Among the American misapprehensions of Britain is that it is becoming Islamic. That is in fact happening — it is notable that a mosque is the only religious structure seen on the train from London to Oxford — but it is consequence rather than cause. Islam did not eradicate Christian England: that was the work of the English themselves, who at some point in the twentieth century decided to adopt wholesale American-style propositionalism as the basis of the nation — even unto their own ruin — and thereby cut themselves off from all they had been and meant. Surrendering the past is surrendering the future for which past is prerequisite.

Yet there is still iconography. The Anglo-Saxon England of one thousand years ago in which the small parish of St Benedict was erected, stone tower and all, was replete with iconography. Men and women alike encountered imagery of the saints, of the faith, of Christ as a matter of routine in their lives. Today the images remain, and today they are encountered daily, but they are of something else entirely. We walked through an Underground station whose long dirty white corridors were decorated with easily hundreds of images of London’s “queer” population. Each icon — let us use the word, for this was the intent — contained a headshot of some sort, with explanatory text below. One of them struck me and exemplified the rest: a man named Fotis, whose pronouns are Ve / Vir. Elsewhere in a train station, we encountered an image of two African women in passionate embrace: its caption reminded the passer-by that “loving who you choose” is what makes Britain Britain. Of course it does not, but it is a purposeful substitution of the new and confected nation for the old and rooted one. The new religion clambers upon the ruined edifice of the old and apes its forms

All this is tutelage, of course. The images of Fotis the Ve / Vir and the like pervade the public square in London for instructional purposes. They teach the English their new narrative, their new understanding of self, and their new permitted ambit of thought and belief. In Trafalagar Square, after telling my son about Nelson, I noted that the crossing lights throughout the busy intersections were not the usual green-and-red walking men. Instead they were sex symbols: literally so, two male symbols intertwined on some crossing lights, two female symbols interlocked on others, and (less common) a male symbol and a female one paired. The regime narrative is that this is intrinsically British, and therefore belongs in a quintessentially British space — never mind Nelson’s own fervent Christianity, which never encompassed whatever this is — and every other space besides. If you thought you were getting away from it while crossing a street, think again. The method is relentless and pervasive, and it works. At Bletchley Park, scene of some of the most intrepid intellectual work of the Second World War, an Englishwoman of a certain age asked me what I thought of it all — and then delivered an apologetic monologue for Britain’s treatment of Alan Turing, as if that was at all the centrepiece of the history there. Yet for her it was. I chose not to share my own view, which was that Alan Turing, whatever injustice done him, was dispensable to the survival of civilisation, but the mores he transgressed were not. It is not that I mind the argument, but the argument is impossible: to paraphrase Rod Dreher, we have lost our reason and can no longer discern.

This too is a regime choice.

J.R.R. Tolkien in his work has Galadriel say that “together through ages of the world we have fought the long defeat”, and this is his England now. We entered the chapel at Oxford’s Exeter College to see the bust of Tolkien there. Though he never worshipped on the premises, it is not the first Anglican appropriation of Catholic glory. There, at the rear of the chapel, behind the golden crucifix, is a large LGBTQIA+ flag. Sir Steven Runciman, in his magisterial Crusading history, records that the Patriarch Sophronius, upon seeing the conquering Caliph Omar enter the Temple Mount, murmured through tears, “Behold the abomination of desolation, spoken of by Daniel the prophet.” But the Patriarch was premature on the matter of the apocalypse, and neither Caliph Omar nor any Muslim has desecrated the church at Exeter College. The long defeat is a grappling with the enemies of the English who are the alienated sons of the English themselves.

England still exists. The English are still here. But they are well into the long defeat, having saved the world more than once and in more than one way, with nothing to save them but their own twilight struggle. At a park in London we met some of the English — and I do not mean some of the British, nor even some of the Londoners, because the woman of the couple told me directly that London and England have increasingly naught to do with one another. You could tell she and her man — they were unmarried but with children — were not Londoners, in the same way you can spot a rural-Appalachia native or a resident of southern Indiana immediately in Brooklyn or on the Harvard campus. I write that without condescension: my family is from south Texas below the Nueces, poor and hard and isolated as it is, and we do not have that luxury. We spoke, and she told me of the rampant crime in her northern town, and the increasingly impossible cost of living, and the fact that she will never be able to raise her children in a home of their own, and the fact that the National Health Service is a shambles, and of her wish that she could move to America someday, where everything is better. I thought back to stepping over sleeping addicts in Paddington station, and observing a man shoot up outside a Westminster restaurant, and the near-identical social evils visible in Austin, Texas, and decided not to disabuse her of the dream, because we’d be glad to have her. It struck me that we were both visiting London as foreigners, but with her it was a tragedy, because this city was supposed to be hers.

It isn’t hers now. It belongs mostly to the regime that propagandises to her that her ancestors were evil and the structures that might have ordered her life are mere restraints to be overcome; and it belongs increasingly to the Islamic population of the city that — unlike the English ruling classes — have the confidence and cohesion to assert and defend their own mores and folkways and traditions. That many of those civics, a term I use very loosely here, are inimical to the English is irrelevant, because they know very well that the regime will protect them in those cases, and they know they have superior Aristotelian philia among themselves. Londonistan as a phenomenon is quite real: I had not seen this many women in hijabs since a brief stint working in Jordan decades ago, and I had never seen this many women in a niqab, ever. We should understand clearly what this signifies. The deliberate process that turned London across the past generation into a city in which the native-born population are a minority — for the first time, it should be noted, in two thousand years — is not malign because of any specific characteristics of the non-native population. The topic of Islam within the West is well covered elsewhere, and in any case a confident and rooted Christian society would neutralise the threats born of social opportunity. I saw a datum asserting that more British Muslims have joined ISIS and al-Nusra in the past fifteen years than have joined the British Army, and this is a massive problem if true, but ultimately one emergent from the flaws in host society, which fails to insist upon itself and its own values. That deliberate process of societal importation is malign, fundamentally, because the process is one in which the regime literally executes what Brecht proposed as mere satire in 1953’s Die Lösung:

After the uprising of the 17th June

The Secretary of the Writers Union

Had leaflets distributed in the Stalinallee

Stating that the people

Had forfeited the confidence of the government

And could win it back only

By redoubled efforts. Would it not be easier

In that case for the government

To dissolve the people

And elect another?

The people are dissolved. Understanding themselves close to dissolution, and instinctually grasping that they are thrust into existential crisis and denied all but pre-political means — they’ve voted time and again against this, and the party institutions of conservatism in Britain have shown themselves worthless at best, antipathetic at worst — they have asserted their Lockean right to appeal to heaven.

Their numbers are however not large, and they will lose to the regime. The prim horror of it was visible across U.K. media, whose figures positively delighted in reporting the persecution and jailing, not just of those who actually committed property destruction and assault, but of those who expressed disallowed opinions on social media. The Home Secretary appeared on the BBC and reassured viewers that Britain remains a free-speech society, while presiding over the expedited arrests, trials, and convictions of those who spoke wrongly. A father of small children got more than three years for a tweet. A middle-aged woman in Cheshire had her arrest announced by local authorities: she posted incorrect information on Facebook. The list is extensive and growing, each destruction of a wrongthink-posting nobody’s life amplified by the regime pour encourager les autres. The 1381 rebellion of English peasants under Wat Tyler ended with the victorious Richard II, having prevailed in part through a double-cross of the credulous rebels, sneering to them that “villeins ye are still, and villeins ye shall remain,” and this is still the message of the regime in 2024. Like the Canadian state ruthlessly prevailing against the protesting truckers of 2022, and like the American state hunting down the its own dissidents — for example California Attorney General Kamala Harris persecuting the enemies of Planned Parenthood — the British state will relentlessly crush its opposition now. Its functionaries have already persuaded themselves that they are victims of a conspiracy — this too was widely discussed on U.K. regime media — and though Americans have lately mocked their pretensions to reach into the United States and extradite the purported instigators of the recent unrest, our own countrymen ought to consider that a left-leaning regime in Washington, D.C., has every reason to cooperate in that process. This is where the Anglosphere is now, each of its great nations gripped by two-tier and dual-track law and justice. Arsonists who burn Catholic churches are unpursued in Canada; rioters who terrorize communities in the name of racial equity are let go in America; and Muslims wielding weapons are unmolested by the British state. The commonalities are not coincidental.

Regimes have philia too.

One of the heartbreaking pleas of the dissident English that did make it through the regime-media barricade was for equal justice under law, for as much police protection for little girls in Southport as for mosques in Birmingham. But this isn’t what policing is for in the United Kingdom. We saw an advertisement for Metropolitan Police recruiting in London with a photograph of an arrested man, and this accompanying text:

You’ve stopped someone

carrying a large amount of drugs.

He’s just a teenager.

He’s exhausted.

He’s scared.

Not giving you his name.

Where he’s from or where he’s going.

He’s broken the law.

But maybe he really needs your help.

So how do you get him talking?

All this is a mindset tell. This isn’t policing to protect and serve the community: it is quite explicitly a recruitment pitch for those who will best serve criminals. (In a rare bright spot for the native population, the criminal portrayed in the ad was visibly English.) Drug dealing simply does not threaten the regime and its practitioners therefore receive lenient treatment. That the preceding sentence also characterizes the Mexican state ought to place British governance in its proper context. If on the other hand that exhausted and scared teenager posted a meme about immigration, well he can just say goodbye to freedom. If the purpose of a system is what it does, then this is what British law enforcement does: it protects the regime. The English pleading for equal treatment and equal protection thereby betray the fatal flaw in their strategic insight, in that they believe they live in the country they deserve.

The country they actually have is nothing like it. It is a country where the regime loathes its people and labors quietly to end them. It is a country where the apparatus of law and order does not see its writ run throughout the land, which is why it cedes space — and therefore sovereignty — to both Muslim militias in England and Protestant militias in Northern Ireland, while pleading with both cohorts for aid in its mission. It is a country where the armed forces are no longer meaningfully capable of executing their core mission of defending the national territory, with the Royal Navy at a near-five hundred year nadir in real capability. It is a country gripped by weird safetyism, in which — I was surprised to learn — my ten-year old son was forbidden to purchase a Coca-Cola because of high caffeine content. It is a country in which signage and announcements in both public and private spaces regularly announce that “thieves operate in this area,” as if it is a meteorological condition, shifting the burden of crime prevention from the actual organizations constituted for the purpose onto the ordinary citizen. It is a country in which it is possible to walk down particular streets, as indeed we did, and see about as much English-language signage as one might see in Cairo, or Tunis, or Khartoum. On the latter, we encountered a money-transfer service storefront called Glory and Honour, that apparently specializes in sending cash to the Sudan. One must admire the branding: it’s the most appealing portal for warlord funding out there.

And yet, and yet: the country they actually have is also the one that is so deeply attractive in its history and inheritance, the one that we do see in ourselves, and ourselves in it. It is the one that threw forth John Keegan’s “filigree of Spitfires” and held the line for embattled humanity. It is the one that wrote epics of heroism and tragedy alike at the Somme, at Arnhem, at Goose Green. It is the one that claimed three centuries of brilliant efflorescence in the sciences and industry, and almostly singlehandedly invented the modern world. It is the one whose culture and literature and language utterly dominated the consciousness of mankind: not merely by fact of the empire, as some would have it, but by reason of its enduring genius. It is the one whose green hills and tall trees and cool summers remind us of Eden when the sun goes low. It is the one where the sense of humanity reached profundities unknown and impossible elsewhere, where the bones of Anne Boleyn and Thomas More lie mere feet from one another in a common chapel, somehow fused into a common heritage that transcend the causes which killed them both. It is the one where we stumble across a wall, and it is a Norman battlement for the suppression of the Anglo-Saxons. It is the one where we come across another wall, and it is a Roman rampart for the suppression of the Britons. Yet where are the Romans now — where are the Normans now?

England remains.

I am American bred,

I have seen much to hate here— much to forgive,

But in a world where England is finished and dead,

I do not wish to live.

— August 2024

This essay was first published on Armas, the Substack of Joshua Trevino. You can subscribe here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.