According to Wikipedia, May 29th is National Paperclip Day. Which nation? I don’t know. But perhaps it should also be International Vaccine Scepticism Day.

Let us start with paperclips and then move onto vaccines. The 20th Century was the century of paper. G.K. Chesterton said that in the Middle Ages if a peasant had found a sheet of paper in the middle of a country lane he would have considered it a sacred object and taken it 30 miles to the nearest church or monastery; whereas in the 20th Century printed paper was so common it was used for wrapping fish and chips, drying boots or keeping tramps warm.

Paper has a long history: from papyrus (vegetable) and parchment (animal) to wood pulp (vegetable again), from scrolls to codices – that’s books, to you and me – and of course from manuscripts that took a month to copy to Gutenberg and his rapid printing press: and then the massed profusion of texts: publishers running around begging figures like Thomas Hobbes and Samuel Johnson let them print whatever they could write, and the newspaper. Meanwhile, official life had already benefitted from double-entry book-keeping: though it was in the late 19th Century that we saw the spread of two of the greatest inventions: the typewriter, which meant that one could produce ‘copy’ in one’s own house or shop, and the paperclip, which meant that one could assemble and store papers without requiring string or binding. What would the 20th Century have been without a sheaf of typed papers held together with a paperclip?

Then we had the personal computer, the word document, and the ‘cloud’, all of which has brought the great century of paper to an end. But I’ll write about the Antichrist another time.

The Wikipedia page on the paperclip engages with the complicated question of who invented it. There are some American candidates, and a Norwegian candidate. The first manufacturer of the paperclip we know now was apparently a British firm called Gem Manufacturing Company in the 1870s. I say ‘apparently’ as no one seems to know for sure. All we know is that the standard paperclip was well established by the 1890s, and that it acquired the name ‘Gem’. But I leave all this to one side. Except that one of the more interesting parts of the story is the claim of Herbert Spencer to have invented the paperclip.

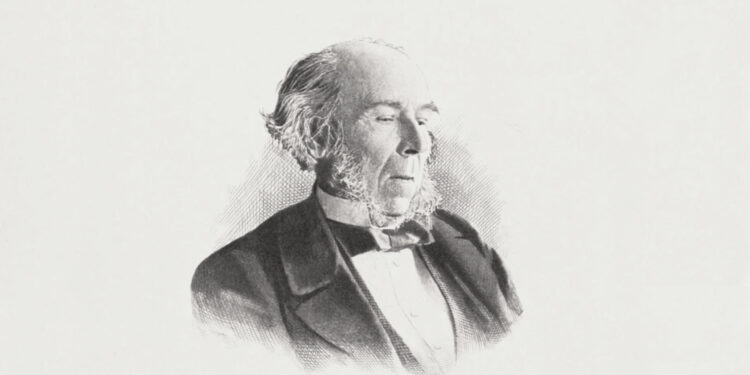

Have you heard of Herbert Spencer? He is one of the Grand Old Men of the 19th Century that no one reads any more: along with Mark Pattison, Thomas Carlyle, Walter Scott, G.H. Lewes, etc. I once went on a pilgrimage to Highgate Cemetery to see Marx’s grave (excuse me, but we are all ‘cultural Marxists’ now; especially if Richard Dawkins is a ‘cultural Christian’): and got a surprise when I found Spencer’s much more humble grave opposite it.

Herbert Spencer registered a patent for a binding pin in 1846 and it was manufactured for a year. Spencer was one of the most famous men of his time, but he was quite proud of his little technological innovation, so much so, that he reproduced an image of it in Appendix I of his Autobiography, published in 1904, a year after his death. The pin looked more like a hairpin than a paperclip: and it clearly has nothing to do with the paperclip as we have come to know it. But Spencer did not pretend otherwise. The purpose of his pin, as he described it, was to bind together loose manuscript pages or sermons or sheets of music, weekly papers or any unstitched publications. The illustration shows that it was nothing like our standard paperclip: because it held together sheets not on the flat, as it were, but at a fold or crease, holding them for ease of turning pages. Contrast the standard paperclip, which, famously, if it has one weakness, is that the gain in firmness of grip is matched by a loss in our ability to turn pages.

Spencer added an explanation as to why his invention had not had much success:

Except in matters of prime necessity, the universal demand on the part of retailers, probably because it is the demand on the part of ladies, is for something new. The mania for novelty is so utterly undiscriminating that in consequence of it good things continually go out of use, while new and worse things come into use: the question of relative merit being scarcely entertained.

We may well tut and chuckle over Spencer’s slightly choleric blaming of the ‘ladies’ for the failure of his little invention.

Spencer, fortunately, had much else in his armoury besides a binding pin. He wrote countless books, and is perhaps the only Englishman since Francis Bacon to have ventured a system of absolutely everything. He invented the phrase ‘survival of the fittest’. He wrote A System of Synthetic Philosophy in 10 volumes, ranging through biology, psychology, sociology and ethics. He wrote a famous political diatribe entitled Man Versus the State in 1884: a book which makes him the godfather of libertarianism. And he also wrote many essays – one of which concerned our second subject – vaccines.

Spencer was a vaccine sceptic. In his collection of essays, Facts and Comments, published in 1902, he included a little essay written some years earlier on ‘Vaccination’. This essay of a few pages registers a very simple objection to vaccines. He had noticed that between around 1850 and 1875 deaths-from-all-causes had dropped in number, while deaths-caused-by-specific-diseases had risen in number as a proportion of the population. He speculated that the cause of the first might be general improvement of conditions; and the cause of the second might be vaccines.

His argument was very interesting. It was that vaccines were implausibly supposed to be what we would now call a ‘magic bullet’: a reagent which would shield a patient from a particular disease – there was no such thing as a ‘virus’ when Spencer wrote – and have no other discernible effect on the patient. He thought this was highly unlikely. He wrote:

The argument that vaccination changes the constitution in relation to smallpox and does not otherwise change it is a sheer folly.

Nowadays we speak of ‘vaccine side effects’. The problem with ‘side effects’ is that it suggests that the vaccine is somehow programmed to take out a virus like a sniper. But is it not the case that the vaccine is rather more like a shotgun than a rifle? Spencer thought it very likely that we would have to watch vaccines for a long time to see how they affect our entire constitution.

Let us call this Spencer’s principle. It is a more brilliant contribution to human civilisation than his binding pin. The vaccine is no more a magic bullet than the British national debt is a magic money tree. The vaccine may – may, I say – cause all manner of effects, not side effects, but central effects. And this may be so of not only our glorious mRNA technology, but also the simple vaccines we have been taught for a century or more to queue up for at school or clinic.

Let us hope that someone will soon, in honour of Herbert Spencer, declare May 29th International Vaccine Scepticism Day.

Dr. James Alexander is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at Bilkent University in Turkey.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

I have just posted this article in the previous thread but it definitely belongs here.

https://www.globalresearch.ca/researchers-call-urgent-action-address-mass-contamination-blood-supply/5858209

“Blood contaminated with prion-like structures from the spike protein raises the risk of inducing fatal neurodegenerative diseases in recipients. The potential transmission of harmful proteins through exosomes (“shedding”) and the risk of autoimmune diseases due to the vaccines’ mechanism and components like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are other major concerns

Proposals for managing blood collection include rigorous donor interviews, deferral periods, and a suite of tests to ensure the safety of blood products

The researchers advocate for comprehensive testing of both jabbed and unjabbed individuals to assess the safety of blood products and suggest discarding blood products contaminated with spike proteins or modified mRNA until effective removal methods have been developed

They call for suspending all gene-based “vaccines” and conducting a rigorous harm-benefit assessment in light of the serious health injuries reported. They also urge countries and organizations to take concrete steps to address and mitigate the already identified risks”

*

A most readable and worrying article.

On a separate topic, I do wish the irksome down-voters could be identified, a la Conservative Woman articles. Their contributors seem to suffer far less from mischievous down-voters, who like naughty children rap on the door and scoot off in anonymity. Perhaps they’d think twice if they were named.

I find the downvoters amusing, as you say, very much like naughty children. I definitely have a couple of trolls who simply downvote anything I post.

Watch this space.

27 up 9 down at the time of writing this.

It’s only Hamster Dick and the Scroteless Wonders. Don’t mind the ever-present shit-munching, shadow-lurking pilot fish. Personally, I find that if I’ve not ate enough roughage to keep up with demands they do quite well on just the barnacles until I get my second wind. They’ll be along to provide the proof of this in just a tick, you watch. They get the hump if I go too long without acknowledging their presence. ( 3,2,1…GO!! )

( 3,2,1…GO!! )

They must lurk with finger poised and senses sharpened ready to pounce and down vote in an instant. Sexual repression I guess. Sad tuesdays.

Thanks shit-munchers. I knew you’d come through for me. You’re nothing if not predictable.

You’re nothing if not predictable. Here’s a small token of my appreciation:

Here’s a small token of my appreciation:

I’m glad to see that it’s not just me (with my “constant complaining”) that finds this behaviour regrettable.

I wouldn’t necessarily be in favour of forcing people to reveal themselves, but I do think it’s kind of pointless especially in a place where I think we are all looking to further our understanding of the world.

Some coherent scientific arguments from the downtickers would be welcome.

Maybe both sides could learn things?

Stop whinging, and scoot right back to the Maryolater Woman articles.

It would be beneficial if up and down voters had to pay the minimum £5 subscription a month …. not sure that that is the case.

A cracking article.

Much to commend in Herbert Spencer’s theory which is why blood transfusions received from “vaccine” contaminated donors must inevitably be dangerous.

Quite. The same tribe who inflicted the blood transfusion scandal on its victims should be in prison, not doling out more blood contaminated with gunk of which nobody knows the long-term dangers.

Yes, ”anti-vaxxers will be the death of us”, blah blah. Remember the incessant tripe spewed by these professional shysters who now want to suck up to you just to get your vote?

https://x.com/JacquiDeevoy1/status/1795404922726367731

”Anti-vaxxers cost lives”…Well at least this poor guy wasn’t one of those. He got the vax ( probably because he listened to Starmer et al ) and subsequently died long before his time due to ”coincidence”. But imagine how much worse it would’ve been? He could’ve been piloting the plane you were on! These sorts of stories are all over online, sadly;

”England: A dad suffering

with indigestion died suddenly.

“I’ve Had My Covid Vaccine”

“Stephen McGowan ‘healthy’ 44-year-old died on a family trip in the Lake District.

“Its believed it was a symptom of a blood clot which caused a fatal heart attack.”

https://x.com/tulloch1978/status/1794864094190985332

It was well known in the 19th c that quackcines murdered and maimed, and saved no one. Alfred Russel Wallace the spiritualist-hermetic quasi natualist; wrote a very good book on this topic using the government’s own stats to destroy their narrative of the safe and effective (the marketing for the poisons has not changed in 200 years).

In his 1885 letter to Parliament, Wallace calls out the fraud of vaccination:

After 70 years of quacking the greatest smallpox death spree occurred in 1871 – 44 K dead in the UK – by law everyone had to be stabbinated. Why then the worst smallpox epidemic in the ‘modern’ era?

No efficacy and lots of harm – the same we experienced with the mRNA fraud during the recent plandemic. Nothing has changed.

Instead of paper clip boy, maybe Wallace instead as the patron saint of the Quackcine Sceptics.

https://peakd.com/health/@reddust/where-did-the-first-anti-vaxxers-come-from

Leicester was the scene of severe rioting in 1885 when forced vaccinations were rejected by the city’s population.

Coincidentally, or not most probably, Leicester was the first whole city placed in to Lockdown during the Scamdemic. The Davos Deviants do like their history.

https://off-guardian.org/2024/05/28/and-the-bird-flu-just-keeps-on-coming/

Kit Knightly at Off-G is still confident that ‘bird ‘flu’ will be used for Billy’s next “pandemic” and probably H5N1 and for which the “vaccines” undoubtedly have already been brewed. The Pandemic Preparedness Treaty and the International Health Regulations hiccups must be a real PIA to Billy and his DD mates.

I don’t think it will be long now.

Nah, everyone knows it’s going to be ‘Monkeybollox: The Sequel’. When does Pride kick off again…..? Obviously it will just be pure correlation and not at all caused by the sudden increase in men attending leather fetish S&M orgies where no-one bothers to use a condom. That would be too much of a stretch ( ”Oooh Missus!” ), therefore don’t kill granny and get vaccinated now!!

Well, every single chicken now has to be registered and will no doubt be destroyed “when” the next scamdemic is announced ….. thereby ensuring that egg consumption will be prevented.

Exactly.

Why on earth do chickens need passports?

Oh, of course, Billy’s next Scamdemic.

The only good thing to come out of covid and the modified RNA ie GMO’s is an ever increasing awareness of the dangers of even traditional vaccines.

This is perhaps the most sensible paper I’ve read regarding vaccinations in general.

Should be freely available in every GP’s practice, med schools and all NHS departments.

Even better if Doctors actually read it instead of being in thrall to bigpharma :-

https://www.midwesterndoctor.com/p/determining-the-risks-and-benefits?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=748806&post_id=144975313&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=false&r=x6a6a&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email

Thanks for the link. A good but very long read.

After reading this it would appear that far from doing good “vaccines” actually cause multiple harms.

For some of us the C1984 has been a blessing in disguise particularly where medicine, as a subject is concerned.

Indeed .

Hopefully it will open a few eyes.

Do you know that wild animals don’t get cancer – Sir Macfarane Burnet, Nobel prize, immunogy.

I’ve often wondered why….

Blimey.

Lots of probigpharma downtickers on here.

Hopefully we’re getting to the bastards.

Hear, hear.

Wonderful article by Dr. Alexander about Herbert Spencer’s unexpected vaccines discovery:

“…deaths-from-all-causes had dropped in number, while deaths-caused-by-specific-diseases had risen in number as a proportion of the population.”

And he came to the correct conclusion, more than a century ago. Let’s hope that “Spencer’s Principle” becomes more widely known.

Speaking of vaccines, here’s today’s example of Mad Cow Disease:

Watch: EU Commission President Pledges to ‘Vaccinate’ Population Against Wrongthink (infowars.com)

Tja paperclip was a sign of the resistance in Norway in WW2.

https://www.warhistoryonline.com/war-articles/unbelievable-paperclip-wwii-resistance-mark.html

Very interesting article. It makes me wonder how many other “enlightened” people from previous centuries have just been forgotten.

As far as I’m concerned, every day is now International Vaccine Scepticism Day.

Seconded

AZ vaccine failure. Dr David Cartland….

https://x.com/CartlandDavid/status/1795492020326215980

Thanks for the link

Maybe we should consider a national Operation Paperclip day.

Operation Paperclip was a secret United States intelligence program in which more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians were taken from the former Nazi Germany to the U.S. for government employment after the end of World War II in Europe, between 1945–59. Some were former members and leaders of the Nazi Party.

Many of these criminals ended up running the UN.

This may focus peoples minds to the levels of corruption that governments will stoop to. Especially from the land of the free and the just.