We know that school closures hampered student learning during the pandemic. But just how bad was the effect? And how widespread? Those are the questions that Bastian Betthäuser and colleagues sought to answer in a paper published at the beginning of last year.

The authors carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of learning loss over the first two-and-a-half years of the pandemic. By combing the literature, including repositories of unpublished papers, they were able to identify 61 relevant studies.

Before running the numbers, Betthäuser and colleagues manually checked each of the 61 studies for various methodological biases, such as confounding. Based on widely used criteria, they determined that 19 studies (that is, 30% of the total) had a “critical” risk of bias. Excluding these from the analysis left them with 42. And since most studies reported multiple estimates of learning loss – for different subjects and grade levels – there were a combined total of 291 estimates.

The authors also checked for publication bias, but found no evidence that the studies with smaller samples reported larger estimates.

So, what did they find? Averaging the estimates for each study and then pooling across studies, they obtained an overall effect size of d = –0.14. This means that average learning loss was about 14% of a standard deviation of students’ test scores. What does this mean in practice? Well, students typically progress by about 0.4 standard deviations per school year, which means that school closures reduced learning by the equivalent of one third of a school year (a whole term). The authors characterise this as “substantial”.

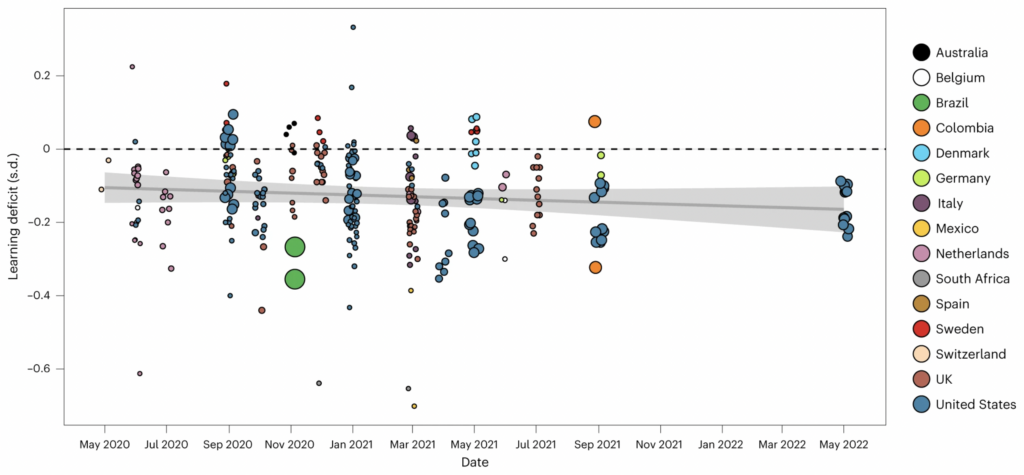

Next they looked to see whether learning loss decreased over the course of the pandemic. Were later estimates smaller than earlier ones? Their chart is shown below:

Here the dots correspond to individual estimates, rather than averages for each study. As you can see, there is no evidence that learning loss decreased; if anything, it increased. However, the authors checked to see whether later estimates were significantly larger than earlier ones, and found that they weren’t. The most reasonable interpretation of the data is that learning loss arose during the first few months of the pandemic (when lockdowns were most severe), and then persisted for the next two years.

Now, it’s possible that students who suffered learning loss will eventually catch up to where they would have been in the absence of school closures. Perhaps if you extended the grey line above into 2023 and 2024, it would begin to slope upwards. Yet as the authors note:

Existing research on teacher strikes in Belgium and Argentina, shortened school years in Germany and disruptions to education during World War II suggests that learning deficits are difficult to compensate and tend to persist in the long run.

Which students were most affected? It stands to reason that those from richer families would be less affected, since their home environments were more conducive to learning, and their parents could afford to compensate by hiring private tutors. And that’s exactly what Betthäuser and colleagues found.

They coded estimates for whether they showed an increase in educational inequality by socio-economic background, a decrease in educational inequality or no change. A large majority showed an increase – indicating that poorer students suffered greater learning loss. The authors also found that learning loss was greater in poorer countries.

So school closures not only disadvantaged poor students relative to rich ones within countries, but also disadvantaged poor countries relative to rich ones. This is obviously ironic, given that many on the left championed school closures and initially denounced those who opposed them.

Betthäuser and colleagues’ study is one of the most comprehensive and careful to date, and it basically confirms what we already knew: school closures came with major costs. What’s noteworthy is that, due to data availability, their sample of studies was skewed toward richer countries. Had it included more studies from poorer countries, the overall learning loss would have been even greater.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Yeah, but they didn’t kill Granny!

Because they didn’t meet up in school they couldn’t spread the Plague among themselves and then take it home and kill the rest of their families. Of course, being avidly engaged in Home Learning none of them were out making nuisances of themselves in public or finding other opportunities to meet and spread the Plague. /s

I think the state did a good job of killing off Granny without the help or family members spreading a virus. If this virus exists considering if you amplify the PCR enough you could find anything, maybe even traces of the Black Death!

Granny could have taken Vit.D, Zinc, HCQ, and/or Ivermectin, but they were verboten.

I know enough people have pointed this out but why are people who write these blogs referring to a “pandemic”…..Even if it exists it was the countermeasures that are the cause of the economic, social etc problems. Or at least put it in quote marks, pseudo or ‘plan’ in front of it.

Thanks for saving me the trouble. Language matters.

Scamdemic.

In an otherwise useful article, that jumped out at me also, stop feeding their narrative.

The terrible learning loss was part of the Globalist plan, as American Patriot Charlotte Iserbyt discovered and exposed after working as senior policy advisor for years in the education department of the US government, and later working in the State Department. She wrote about it in her book “The Deliberate Dumbing Down of America”. She said the motto was “Target the Resisters”.

Deliberate Dumbing Down of America

The “New Feudal Order” needs the serfs to be uneducated, as they were in the good old Mediaeval days of Lords & Serfs, without a pesky middle class to interfere.

A terrible situation you can take hold of these children and try and bring them up to scratch but the emotional damage has already been done.

Dumbing down the children is essential if they are to swallow the utter bullshit that is Nut Zero. And Nut Zero is probably going to be the biggest game in town for the next fifty years.

It’s like Inflation, the effects are accumulative.