Everyone is contributing their opinion about the Garrick. Is the Garrick able to admit women as members? If not, ought it to do so on principle? If principle is unforthcoming, then should it do so as a result of the intrusive harassment of the Guardian newspaper? It is tempting to make mock, as the whole debate is a bit of a swirl in a latte mug. But the world à la mode is always a bit like this. Teacups storm; then twitter storms; somewhere or other there is reputation-destruction or old fashioned scapegoating, and the world continues on its way.

The Garrick, if I understand the story, requires a two-thirds majority to change the rules; but some lawyers have counselled that the rules already permit women to be admitted as members. What is odd is that the issue has arisen in an atmosphere of moral affront and certainty worthy of Miller’s Crucible. Sting will resign. He will not stand so close to anyone refusing to admit women as members. So will Stephen Fry. He will use the Garrick as his washpot instead of Moab. So will Mark Knopfler, on the grounds that the argument wouldn’t be convincing enough if only one Geordie musician chimed in. Why aye, there have to be two of them – and in harmony. They don’t want the Garrick to be money for nothing and the chicks for free: they want the chicks to pay their fees too.

This – the Garrick – is a thorny subject. Boris Johnson wrote about it in the Mail, though he seems to have written his piece with a certain someone looking over his shoulder. Everyone in the world knows that Boris has two hands, neither of which knows what the other is doing unless it reads the other’s copy. One hand wrote: 1. Don’t force the Garrick to admit women as members. The other hand wrote: 2. The Garrick should admit women as members. Let us try to be of sterner stuff: which, in the first instance, means writing without imagining that the thorn in the flesh is looking over one’s shoulder.

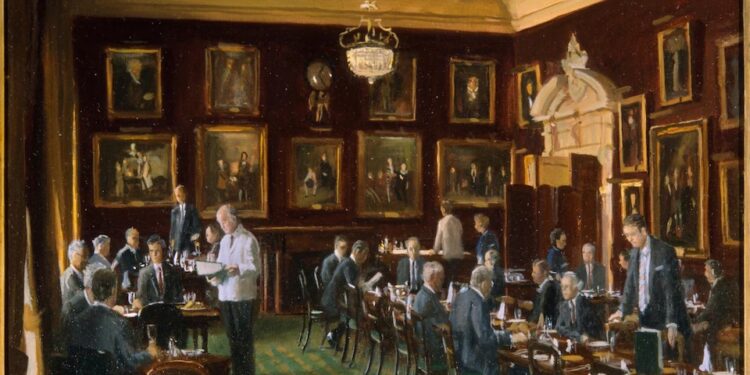

As usual, the only way to make sense of this is to relate it to the longest possible history. A few centuries ago there was nothing wrong with men spending time with men. The world was full of monasteries, colleges, guilds, clubs, associations: and latterly the great London clubs, which were formidable in the 19th Century. The Reform was founded in 1836 – it admitted women in 1981. The Athenaeum was founded in 1824 – it admitted women in 2002. The Carlton was founded in 1832 – it admitted women in 2008. The Garrick was founded in 1831 – and it hasn’t caught up with the fashion yet. Suddenly, the Guardian has got out its moral spray can, and everyone from Simon Case downwards has had to signal his particularly conformist virtue by resigning or threatening to resign or resigning.

I have no axe to grind. I am not a member of a club. Peter Avery, an old Persianist, once suggested that I should join a club. And David Barchard, former FT correspondent to Turkey, was surprised when I said I had nowhere to stay in London. They were clearly fooled by my massive forehead, respectable dress and severe deportment into thinking I was someone who would value such things. Well, not so. I was never very clubbable: I was in fact ‘his own man’, as was sometimes said disapprovingly in my wake. But there is a principle at stake, as usual, and I suppose it is always worth offering a word for the sake of a principle, even an obsolete one.

The question is whether all our institutions are – to use the now famous Gramscian phrase – to suffer from the long march of women through them. And whether – rare question (noblesse oblige requires its not being asked in mixed company) – it is good for all our institutions to have the hand of the gentler sex on the keys, the till and the rulebook. Let us be sceptical – maybe it is, maybe it is not – and let us also marvel at a world in which everyone, including our great celebrities of the 1980s, suddenly find they all agree on the most pressing controversy of the age.

The principle is to do with truth. Like many others, I think ‘the truth’ has always had a vexed status in the world: but that it seemed to count for very little, very suddenly, in 2020. Why was this? Well, one obsolete possibility is that it had something to do with all the women in the room.

On August 6th, 1831, Samuel Taylor Coleridge said the following:

There is the love of the good for the good’s sake, and the love of the truth for the truth’s sake. I have known many, especially women, love the good for the good’s sake; but very few, indeed, and scarcely one woman, love the truth for the truth’s sake. Yet without the latter, the former may become, as it has a thousand times been, the source of persecution of the truth – the pretext and motive of inquisitorial cruelty and party zealotry.

This is fascinating. It might be true, or not true – even though it might not be considered good. Discuss. But one cannot discuss it unless it is said. And one can imagine it being said in the historic Garrick. But one cannot imagine it being said in the current Garrick or the Garrick of the future if Stephen Fry, Gordon Sumner, John Simpson and Mark Knopfler are to have their way.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge was rather clubbable: he liked talking at great length, though, according to Madame de Stäel, he lacked a capacity for conversation: being a monologist. (Read Coleridge’s Table Talk, which is incredible.) D.H. Lawrence, on the other hand, was not particularly clubbable. He visited Cambridge once, met Russell and Keynes, and thought of spiders. He married Frieda and spent most of his life in exile with her – Italy, Australia, New Mexico. He considered the most fundamental relation in the universe to be the one between a man and woman in marriage.

But even though this was the case, he had a hankering after something else. Birkin’s last words in Women in Love are “I don’t believe that” when Ursula tells him that the love of a woman is enough. And in Kangaroo, the female character cries when the male talks about sharing activity with men: “Her greatest grief was when he turned away from their personal human life of intimacy to this impersonal business of male activity.” This impersonal business of male activity. Notice the binary here: Lawrence associated masculinity with impersonality and femininity with personality. Discuss. Or, let’s say, if you are reading this silently (and not out loud over oysters and champagne to the women in your clubroom), Consider.

I suppose I have to be provocative and suggest that if there is such a thing as ‘impersonal male activity’, and that if this is valuable, then it may be difficult for this to be understood in a modern world in which women are marching at length through our institutions and revising the rules of those institutions in relation to an inability to respect or understand ‘impersonal male activity’. Now, this ‘impersonal male activity’ might be a bit foolish, like the braggarting of boys. Peter Martland, the historian, once told me that Corpus Christi College, Cambridge changed immediately as soon as women were admitted. The dining hall had formerly been a place at which more food was transported by sporting projection than by tray: now it became a genial and genteel café of chivalry and courtship. But sometimes this ‘impersonal male activity’ might be extremely important: especially if Coleridge is right and men will occasionally consider setting aside the ‘good’ for the sake of the ‘true’.

COVID-19 was an exquisite exhibition of the politics of the (apparent) ‘good’ triumphing over any concern with ‘truth’. And when I say ‘triumphing’ I am alluding to the grotesque display of glorification, intimidation and humiliation which was found in the original Roman triumph. See Mary Beard for details. There were women who were critical of the pandemic protocols (not, however, Mary Beard): the ones I admired were Laura Dodsworth, for investigating ‘nudge’, and Laura Perrins, for unlimited moral scorn. But even they were better at observing what was ‘not good’ rather than what was ‘true’. I imagine that many readers of the Daily Sceptic relied on podcasts – and mostly podcasts involving conversation between men. As everyone knows, the BBC has long insisted that there is no such thing as broadcastable conversation between men. There must be a woman in the room. Is it not significant that there was, and is, a taste (at least among men) for conversation between men – conversation with risk of boredom, since it has impersonality in it, but conversation also with risk of truth? London Calling, the Lotus Eaters, Louder with Crowder offered male conversation and something like a proper scale of values, not wholly created by the situation. For me, the most significant encounters of the pandemic were Delingpole-and-Yeadon and Weinstein-and-Malone: they convinced me that everything was worse than I thought (as if the surface of reality was not bad enough): and, in those conversations, even if the truth was not known, the truth was spoken about as if it mattered more than anything else.

I doubt the fuss about the Garrick is of any importance. There is a great moral fear of not being ‘egalitarian’ among our elites. And so they are falling like dominoes or playing cards: pretending that their collapse is a consequence of morality. But there is a principle at stake, and even if this principle is not one anyone is likely to defend or even consider nowadays – on the grounds that it is ‘not good’ to consider it – there is an awkward question about whether our civilisation is not in danger for yet one more reason, which is that in our institutions we seem disinclined to let men talk about anything without a woman somehow being involved.

What is truth? Does anyone care about truth? Is there a possibility that truth has been completely mechanised into ‘my truth’? If so, this means that when we talk about ‘truth’ nowadays we are actually talking about something that is ‘good’ in some respect – possibly only good for the speaker, though admittedly also possibly objectively good – but certainly not ‘true’.

Dr. James Alexander is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at Bilkent University in Turkey.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Coming soon to a street near you.

I said months ago, once they fire on their own people all bets are off.

Maybe they’ll try it in Belfast first, just to see what happens.

You should be watching bozo and quaking in your Chelsea boots.

Yep, things warming up

Will be interesting to see what happens tonight

I said on TCW at the start of this shitshow that we’d see troops on UK streets with live ammunition before it was over. Didn’t go down well.

It looks as if the police and army will not comply with the regime…rumours are coming out that the Austrians have backtracked on compulsory vaxxings.

I do not see why our police would wish to enforce this murderous power over their fellow citizens..I see many refusing and joining us.

Our best hope is from a refusal of these forces to carry out illegal orders. They have a statutory duty to refuse illegal orders.

I wouldn’t bet on it. The higher ‘elite’ (pseudo-)military are selected for native psychopathy. That makes it easy for them to carry out acts of evil.

Speaking from personal experience: no they’re not

Indeed Paul…

Let’s face it my dear fellow skeptics, this has not been the best of weeks as we move toward the globalists Dark Winter phase.

https://twitter.com/LozzaFox/status/1461793416283672581?s=20

Add in the inconvenient truth uptick with Covid hospitalizations among those double-jabbed but not yet boosted, and the moral of that story is? Simply inject the sheeple with evermore doses of snake oil that’s already not working – if they refuse and don’t volunteer for it – your benevolent Govt will then find a new way to force you… aka what’s going down in Austria – achtung seig vial!

That vaxxing at all costs option hasn’t worked out too well for the Gibraltans has it? Remember when they said if you took the jab and wore the face nappy, you’d get your freedoms back?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4jzevzs25RQ

Meanwhile across Africa… where the masses are hardly vaccinated at all, they take HCQ and Ivermectin as prophylaxis treatments, and guess what? There is no raging Covid pandemic in that region at all. This useful information has been neatly crushed and airbrushed away by the western presstitute MSM most paid-off and levered by the Gates Foundation. As has the important fact that natural Covid immunity is far superior to any current injectable.

I wonder what the real reason could be for this massive gaslighting of the British public by our trusted NHS and the institutions like the BBC?

Finally, this latest vid from Del is a must see

https://www.bitchute.com/video/EhYBHZlIRyv2/

Be seeing you…

Del Bigtree the High wire, a true journalist I wish to God we had his equivalent here

We do. UKColumn news, every Monday, Wednesday and Friday.

https://www.ukcolumn.org/

At 1pm.

‘Meanwhile across Africa. . . there is no raging Pandemic in that region at all”.

The other day a reader posted a link to a video saying unkind things about Pfizer and the dangers its products posed.

This was accompanied by a pop-up ad (unusual these days) by Pfizer itself extolling its virtues for the way it is negotiating preferential terms for supplying vaccines to developing countries, presumably including those of Africa.

Watch that space.

“Police spokesperson Patricia Wessels confirmed that police fired shots, though it was not immediately clear what type of rounds were fired.”

Well, that inspires confidence in the Police! Don’t even know what kind of bullets they used? Perhaps Alec Baldwin could advise?

Will it be continental style, or just a ‘Very British Civil War’?

However, this is not unusual for the police to act in this way. Rather it is the UK (but not NI) who are the exception to the use of paramilitary police to control rioting.

Besides these shots would seem to be rubber bullets (at the time of me writing this). A convenient fact that the British press have not written about.

Rubber-coated bullets are just less-lethal than the real mccoy. Reduce the range and they can kill just as well.

Last quote in DS summary of the article.

“We fired warning shots because the situation was life threatening”

Beyond parody.

Yeah, I love that “We killed them all because they were endangering themselves and could have been hurt”.

It’s all about health….and safety. Sorry, I know that’s getting old now.

Your name is awesome btw. Reminds me of a woman I used to know, Halina Hann de Basquette.

Reminds me of a friend of my Dad’s, a chap called Tony Hole. His parents had saddled him with two middle Christian names which began (I don’t know exactly what they were) with R and S. A very nice fellow with a good sense of humour- which, obviously, he needed.

When I was a grammar school, we had a rather unpleasant deupty headmaster called Mr Bates. For some inexplicable reason, his son was allowed to attend the same school. I have no idea what the son’s forename was. He was known universally as Master Bates.

It was not for the policemen who were under attack.

“We fired warning shots and there were also direct shots fired because the situation was life-threatening,” she said.

Is an admission that they fired live rounds

All dutch police are armed with pistols. Armed police will not allow themselves to get into wrestling matches or be overpowered as they could have their firearms taken from them and used against them

It was definitely the ‘pop pop pop’ of small arms fire you could hear in the videos.

It is all on video, their was no life threatening incidents occurring, they shot them because they were ordered to do so. At least be honest about it.

Ironic beyond belief that it’s the ones with the guns who felt their lives were being threatened

I always found the presence of pistol packing local cops in Amsterdam quite comfortable and, as individuals, they were very easy to chat with.

I expect the shots in Rotterdam were fired by some sort of outside riot squad.

However apparently pleasant, it is in the nature of cops to do as they are told.

Riot Squad as later confirmed.

Many revolutions achieve initial success when armed police or militia decline to shoot or even join the people without even knowing the political aims of those directing them.

While no liker of hippies there is no denying their success in placing flowers down the barrels of the guns that US National Guard were supposed to use against them.

The State National Guards have day jobs and so are ‘of the people’ unlike the military.

Charles de Gaulle once pre-empted an insurrection by senior army officers by issuing all grunt conscripts with new fangled transistor radios, thus equipping them with sources of information other than their own NCOs. They subsequently refused to back the coup and came out in support of The People.

That is the usual m/o when it comes to the planned use of violence against citizens of a given locality. In the UK, the Met are the usual suspects.

And what is so ironic about it? Wanna see you standing there with a gun feeling unthreatened while a couple hundred people keep hurling stones and molotov cocktails at you or setting your car on fire.

I’ve never understood why rioters ‘against The Man’ feel it worthwhile to burn some poor guys moped.

Even more so those who think it worthwhile to loot the Pound Store.

Things are getting nasty – big showdown in Austria this weekend.

Divide and conquer. It is all going perfectly to plan for Gates et al

Indeed. Event 201 war-gamed the riots. It is expected and has been planned for.

That said, just because you can’t win, doesn’t mean you don’t fight.

I want to be able to look my children in the eyes and tell them I fought for their freedom.

Guerilla warfare usually wins – just takes time. Focoism (Che Guevara’s doctrine of inspiring ‘the people’ by example of violent actions) may not work, but then again stranger things have happened.

Who says you can’t win?

“Local media reported that at least 20 people were arrested.”

How did they get arrested with all their fellow protesters looking out for them? Or did they just stand by and film it on their smartphones-Made-in-China?

Why don’t the protesters arrest the Police for a change?

Because the police are armed and will protect their monopoly of violence.

100 protesters charging down on one policeman firing a gun – which 6 will he choose? 94 remaining.

So you’re happy to be one of the six?

Better odds than taking the ‘vaccines’!

It shouldn’t come down to a battle with the police anyway, it is the politicians and those making the money out of ‘Covid’ that should be brought to heel.

Faisal Shoukat of Halifax is one that comes to mind – start with that scammer.

Better than being one of the ‘6 million’…

It came to that in Poland; it came to that in Romania. We’re not at that stage, obviously.

It doesn’t come down to that. Police operate on the basis of overwhelming power. The moment it gets even slightly hairy for them they either (a) overreact in a desperate attempt to assert overwhelming power or (b) they bail.

The balance against the police is far far more precarious than it appears. Its mostly a confidence/intimidation trick.

“We fired warning shots”! Who gave the order I wonder? Looks like the Police are now the terrorist arm of these terrorist “Governments”

Anyone know where to buy a gun, a very big gun.

First apply for a licence.

Why not pop into Tesco’s for some fresh fruit?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F4PZXuk3TsM

Guns (sic). In the States, where the police know a thing or two about violence & weapon trauma, most cops (and combat experts) rate a close range knife at least as deadly as a firearm.

Don’t be complacent and think that it couldn’t happen in the UK. We are not safe from our own “unarmed” police.

As can be confirmed by hundreds of (ex)coal miners.

Pay (aka bribe) them enough and the police will do pretty much anything the paymaster orders. Police were transported from parts of the country not sympathetic to, or associated with miners, to crush them. In this part of East Anglia, the remuneration for clubbing miners and pushing their women around was so good that the number of fishing boats, new cars etc. suddenly acquired by policemen was impressive.

Police were transported from parts of the country not sympathetic to, or associated with miners, to crush them.

That’s how the Army will be deployed if and when Sir Humphrey deems it necessary.

Good photo. Wonder how many of those in police uniform were squaddies?

Shot for refusing a medical intervention!! That the manufacturers won’t accept liability for!! Our own police ask protesters blocking the M25 if there is anything they need so we’re ok. ……..

Medical intervention in the sense that it’s stopping the immune system from functioning, potentially hindering cancer cell repair and making people sick. Useless and with new data in this new paper below, the ‘virus’ is likely bacterial pneumonia usually fixed with antibiotics (oh and ivermectim works as well). What a house of paper cards. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355574895_Nature_of_the_COVID-era_public_health_disaster_in_the_USA_from_all-cause_mortality_and_socio-geo-economic_and_climatic_data

More likely shot for setting police cars on fire.

Well…. Peaceful protests haven’t worked. I’ve said this for months! The governments have tightened the screw. Violence is now the only way. I don’t care about the police getting hurt. They’ve chosen their side. You will soon see a world leader being dragged on to the streets. They will never be able to walk down the street safely again and bloody good!

“Peaceful protests haven’t worked. I’ve said this for months!”

Join the club. Now expect a barrage of downticks!

302nd Assault Company (‘Evicerator of Tyrants’) has formed in Chipping Sodbury, so i’ve heard…

Reports of large number of shell casings in the streets

Reports of at least one shot dead by police

‘Twenty injured’ suspect the numbers of those shot dead by the police will rise during the course of the day

If the police have indeed murdered protestors, the Dutch should hold a massive vigil during curfew time. That will pose a dilemma for the state …

Is it too much to hope that eventually there’ll be a day of reckoning for the willing participants in their Government’s violence against their own people?

Did the policemen who whacked the striking coal miners in Britain in the 1980s with their batons ever face a ‘reckoning’?

With respect to the miners, we are in WWIII right now. When we win, there will be carnage – the ‘mob’ don’t hold back…

No, sadly not, and neither did Thatcher or any of the police chiefs. But many Plod families had to move away afterwards.

This response from the people was always going to happen. Humanity has been bullied, vilified, mocked and humiliated, by their own governments and their ‘globocops’ – something had to give.

And as for using live rounds on their own people? Barbaric behaviour and not worthy of a so-called democratic society. All eyes on Vienna now.

The Guardian

‘Police in Rotterdam have fired warning shots, injuring protesters, as riots broke out at a demonstration against government plans to impose restrictions on unvaccinated people.’

It’s hardly a warning shot if you actually shoot someone dead

What would be the warning then? ‘Do that again and we will shoot you dead again’?

We shot your friend, it could have been you…

I want the media liars punished, not just the politicians. Both created this situation. It’s Just War all the way, now.

Hopefully it won’t be another ’80 Years War’ aka Dutch War of Independence from the Spanish.

Violence is the answer. Politicians don’t hand back powers they have to be taken back, by force.

Seems the Clot Shots aren’t culling the people fast enough so they now resort to shooting them.

Words are important

NOT

‘Shot by the police’

BUT

‘Murdered by the police’

Protest today in Amsterdam

Not ‘shot with the police’ then?

Shooting us to Keep us safe.

Don’t forget you need booster shots to be fully shotinated.

Excellently researched article on this link. Banned, of course, because they hate the truth, by Facebook et al.

https://dailyexpose.uk/2021/11/03/uk-has-fallen-85-percent-covid-deaths-vaccinated-child-deaths-83-percent-higher/

Kulgen macht frei

Feel free to write to the Netherlands Tourist Board to ask where you can go without being shot!

https://www.holland.com/global/meetings/contact.htm

Just e mailed this

Dear Eric

Hope this email finds you well

I am considering a holiday in your country

Before I make a decision, is it possible that you could give some reassurance that your police will not murder me

Sad to see the country that murdered Anne Frank revert to type

Then again perhaps I’ll give it a miss

Resistance Playlist

‘Le Prophete, opera: Act 3, Coronation march’ – Meyerbeer

‘Hate To Say I Told You So’ – The Hives

‘Step Down’ – Sick Of It All

‘Bring It On Down’ – Oasis

‘Scratch the Surface’ – Sick Of It All

‘Blood Brothers’ – Papa Roach

‘Longsight M13’ – Ian Brown

‘Last Resort’ – Papa Roach

‘London Calling’ – The Clash

‘Learning to Fly’ – Pink Floyd

‘Clampdown’ – The Clash

‘Sabotage’ – Beastie Boys

‘I Ain’t Goin’ Out Like That’ – Cypress Hill

‘Back On the Block’ – Fun Lovin’ Criminals

Don’t forget the 2013 song Pandemic by Dr Creep, with the line, ‘2020 coronavirus bodies stacking up’.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5P77bUdE4p4

Thanks for that. My list is obviously personal, but is something to keep us all holding that line: indignation and hope. Gotta stick together, folks.

Lockdownsceptics.org had a longterm daily item featuring appropriate music titles proposed by readers, must have run into hundreds.

I don’t know if it’s still in an archive somewhere.

My own favourite contribution was also Xmas appropriate

‘There ain’t no Sanity Clause’. The Damned

The Manics , If you tolerate this !!..

And so it begins.

We are killing our kids. Does anyone care?

Kids that would have never died from COVID are now dying after getting the vaccine. Will it ever end?

“Recently, Dr. Toby Rogers did a risk-benefit analysis showing we’ll kill 117 kids for every kid we save from COVID with the vaccines aged 5 to 11.

The ratio doesn’t really change if they change the dose, e.g., to a third of the adult dose. It means fewer kids saved and fewer kids killed, but the ratio remains about the same. We will kill a lot more kids than we will ever save with these vaccines.

What Toby predicted is now coming true.

We can’t show it is 117 to 1, but we can show for sure we are killing more kids than we are saving.

With COVID, only children with pretty severe health problems would die: we don’t know of a single kid, 5 to 11, who died from COVID who didn’t have some pretty serious health issues before they got COVID.

Those days are now gone. We’re now killing the healthy kids.

The vaccines rolled out for kids 5 to 11 starting on November 7. It is now just 12 days later and we are now killing perfectly healthy kids.”

https://stevekirsch.substack.com/p/we-are-killing-our-kids-does-anyone

my nephew turned 12 yesterday. In France. His birthday present? He will be taken to get his clot shot so that he can “participate” in society.

My heart is broken.

New study from Germany confirms higher vax coverage –> higher excess mortality

https://stevekirsch.substack.com/p/new-study-from-germany-confirms-higher?r=o7iqo

The Harvard study showed vaccination makes things worse as far as cases goes. This new study from German shows that the more you vaccinate the more people get killed. Not a surprise to me

What this new German study shows is: The higher the vaccination rate, the higher the excess mortality.

I can’t say I’m surprised. These are the deadliest vaccine in human history by a factor of over 800. But it is always nice to get confirmation from multiple sources who have no conflicts.

The authors write (translated into English): “The correlation is + .31, is amazingly high and especially in an unexpected direction. Actually, it should be negative, so that one could say: The higher the vaccination rate, the lower the excess mortality. However, the opposite is the case and this urgently needs to be clarified. Excess mortality can be observed in all 16 countries…”

In plain English: vaccination makes things worse, not better.

I wanted to share this study with you because it might be interesting for you and maybe you want to add it to your vaccine data.

https://www.skirsch.com/covid/GermanAnalysis.pdf

Lack of compliance is the way to go, no downloading of the vaccine passport & non-violent protest. The powers that be want a violent uprising as they can then castigate us leading to further division, hatred & derision of our stance.

This article, which pulls together all the latest immunological & virologic research on the effect of the covid jab on the human immune system, makes it perfectly clear as to why we must keep strong & hold the line.

https://trialsitenews.com/the-original-antigenic-sin-covid-19-vaccination-and-sub-optimal-initial-immune-priming-deranges-the-antibody-cytotoxic-t-cell-immune-response/

I tend to agree with you. Nevertheless not all violence can be controlled, and there will come a time (if compulsory jabs lead to people being forcibly injected) when just a passive lack of compliance will be the same as complying with their demands. Then it’s ‘Warsaw Uprising’ time, or eternal shame.

At that point it becomes physical assault, whole different ball game. Until then the Resistance needs to keep the moral high ground with civil behaviour. The only cover of the protests in the MSM is when violence against the authorities occurs. The narrative continues…

So we need a multi-pronged strategy, including a range of tactics. Shame no bugger in the public realm has put his neck out to lead! This could be a bloomin’ anarchists’ revolution yet…

The assault on anyone challenging the narrative is vicious. FB in particular. Apparently I have an Agenda…. ie my position of challenging what is put out by officialdom is too threatening & anything which causes cognitive dissonance is derided without any engagement.

I don’t do social media for this very reason, but sympathise. Against huge odds for now we can only resist by staying true to our principles and living on our own terms. Sadly this means we are spectators of the rise of tyranny in our midst, even if we dodge its clutches. Just have to do what we can, there is no shame or guilt in being ‘ineffective’. But it may sow seeds for the future (millions read this site around the globe).

Thank you for the article. I enjoyed and duly forwarded it.

While the author doesn’t say it, I will.

These ‘vaccines’ were designed to promote and continue a pandemic. Not to stop it.

He has in private said exactly that.

To be published he has to stick to the medical evidence.

I’m glad that you enjoyed it & have passed on the flame.

I grow more confident with every passing day, and report such as this, that my decision is the right one.

It has come to my attention that schools in England are now requiring PCR tests rather than Lateral Flow tests at the first signs of respiratory or any other form of infection in children.

Until recently they required Lateral Flow tests and PCRs were pretty much optional. As we all know PCR tests are open to abuse in a number of ways:

-The gene targets can be altered by the NHS with no notification to the public so that they match genes that are shared with common coronaviruses if not even influenza viruses.

-The cycle thresholds settings are set so high that anybody with even a minor exposure to SARSCoV2 in the last two months who is completely immune and would never be able to infect anybody else tests positive.

-A combination of the two above, can result in a scenario in which when children develop influenza the PCR then reads as a “positive to SARSCoV2”, when it’s merely influenza in a child fully immune to SARSCoV2

-The most worrying thing is if this is happening in the age bracket of 5-11 year olds, as a form or fear manipulation for these parents to get their children injected.

If your or anybody’s children develop influenza or cold like symptoms and you are not able to refuse the PCR test, and this comes back positive, please double check it with a Lateral Flow test at home. If the Lateral Flow test/s are negative, then please inform other parents who are ready to hear this.

https://t.me/s/robinmg

They can fucking require all they want

If you love your children take them out of school and never send them back

LF give blanket false positives to boost the numbers.

PCR cycles are run differently based on vaccination status.

So much for civility of the mighty venerable European Union

still if it saves one life…

I counted 21 gunshots in that 2 minute clip

It appears from the video clip that the police are firing from moving vehicles

Indiscriminate shooting of protesters

The police were never in any danger in this clip

“Rise like Lions after slumber

In unvanquishable number

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you

Ye are many – they are few.”

― Percy Bysshe Shelley,

I wonder if Arnold ‘screw your freedoms’ Schwarzenegger has commented.

Terminator. The prophecy fulfilled.

Who’d have thought that civil unrest and possibly even conflict on European soil once again could possibly be triggered not by the threat of communism or Islamism but by the threat from our very own western governments who are behaving like power-mad tyrants.

Freedom is not given, it is taken.

Shooting people for their own safety, is like fucking for virginity.

Full on fascism.

Wonder if one day soon we’ll see a “Ceausescu moment” when our leaders finally realize they have badly miscalculated and will have to face the music.

If this goes on for long enough, the boombabies will eventually bring out machine guns to defend their democracy against those misguided miscreants who erronously believe they were also humans with rights.

Reports started by saying the Dutch police had shot protestors. By the time it got to the BBC’s lunchtime news today, the protestors had become “rioters” and the police had to shoot them in self-defence. Now that’s what I call spin!

Joe Rogan said his doctor, Pierre Kory, is part of a group that has used Ivermectin to quietly treat 200 Members of U.S. Congress for COVID19. Dr Simone Gold, from America’s Frontline Doctors, told that she has prescribed treatments for Congress. She still believes in her oath, but she is vocal saying she has been contacted by many in DC. Can you believe these demons? Healing for them are OK but not for us. Get your Ivermectin while you still can! https://ivmpharmacy.com

‘Two protesters have been shot and wounded by police to protect public health’. Bitter irony

It’s call “The Social Contract”. We agree to work together, as a society, for everyone’s benefit. When that social contract is breached, society breaks down.

Treating people, who care enough about their health to resist an experimental, unnecessary medical procedure, as criminals will do far more damage than Covid.

So there we have it, our political mediocrities/masters choose to destroy the economy, hamstring the life chances of the young and sever the cohesion of society- all for a virus with an IFR of 0.15%

i might be wrong here but the people who die from Covid are pretty much going to die from Covid ,im not going to kill them by not having my third vaccine that doesnt seem to work get a fucking grip and PROTEST they cant kill us all as my dad used to say

The early indications are that people have finally had enough. Even the BBC is reporting the riots. I hope our own Government takes note. It is the younger generation whose lives are being screwed up. We need to rule out any further lockdowns in the UK regardless of case numbers and openly support herd immunity and focussed protection. For the rest of us let it rip. It is impossible to protect the population from every day risks. It is time for everyone to get a grip.

“Two protesters have been shot and wounded by police to protect public health”

That makes it all right, then. Shooting political opponents for the greater good.

I remember the cries of ‘The evil dictator /Saddam/Assad/Boogeyman-du-jour is killing his own people’. Where are the cries now?

There needs to be some organisation on our side. Groups to keep an eye out for plain clothes cops infiltrating to take out perceived leaders (as seen in the Rotterdam videos). The cops are likely to be big lads working in pairs dressed in too-clean casual clothes – ironed jeans are a dead give away! Swarm them.