In March 2023, the BMJ published an article by professors Stephen Reicher, John Drury, Susan Michie and Robert West entitled ‘The U.K. Government’s attempt to frighten people into Covid protective behaviours was at odds with its scientific advice‘. You will note in the declaration of competing interests that they were all Government scientific advisors. All four sat on SPI-B (the U.K. Government’s Scientific Pandemic Insights Group on Behaviours) and two were also part of ‘Indie SAGE’.

In essence, the article claims that the idea of using fear to induce compliance with lockdown and NPIs did not come from the Government conspiring with behavioural scientists in SPI-B, but rather from ignoring them. Not only that, they say fear is an ineffective way to persuade people engage in ‘health protective behaviours’.

This article stuck in the craw after the extensive research I had undertaken for my book A State of Fear: How the U.K. Government weaponised fear during the COVID-19 pandemic. I don’t deny the Government’s own agency in using fear but to claim it was at odds with official scientific advice is patently untrue.

The article opens with the shocking leaked Government WhatsApp messages in which the former Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Matt Hancock openly proposed using fear — “we must frighten the pants off everyone with the new strain” — and Cabinet Secretary Simon Case agreed that “the fear/guilt factor vital”, offering lurid insight into their base and disrespectful attitude towards the British people.

But was it right for Reicher et al. to claim the Government acted against its own scientific advice? Or did these embarrassing leaks happen to offer an excellent opportunity for SPI-B members to distance themselves from the egregious use of fear?

The professors’ article then went on to use a hard-hitting article which appeared in the Telegraph in May 2021 to further back up the idea that it was the Government which aimed to control the public through fear. Well, I have a little insight into that article, since every single quote came from the anonymous interviews I conducted with government advisers, including some of their colleagues on SPI-B. One told me that “the way we have used fear is dystopian”. Another crowed that “without a vaccine, psychology is your main weapon… Psychology has had a really good epidemic, actually”. And yet another adviser told me that he was “stunned by the weaponisation of behavioural psychology”. These were Reicher et al.’s contemporaries and colleagues — not the Government — breaking cover to express their discomfort and concerns.

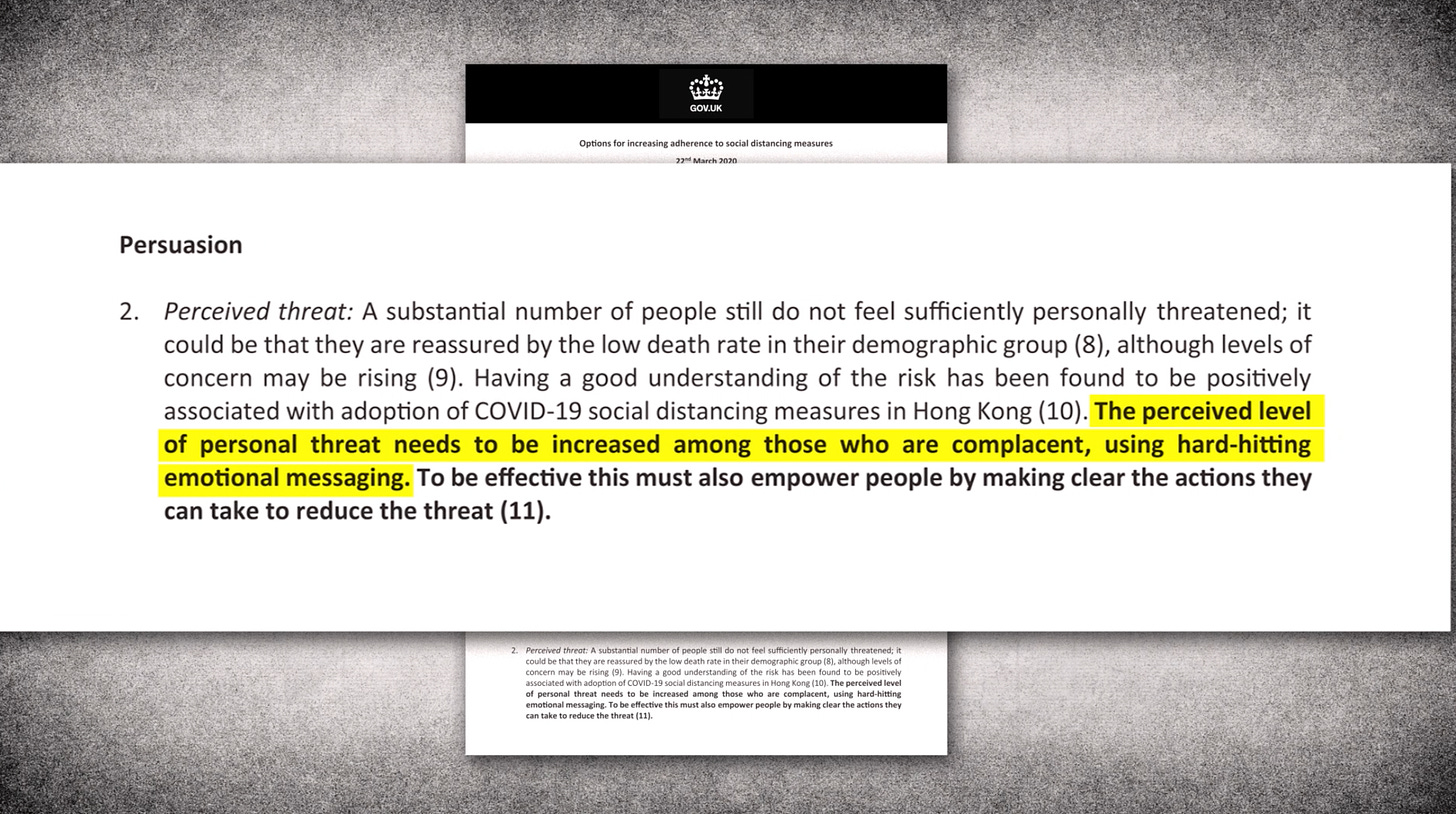

If my first concern with this article was the flagrant denial of the advice contained within the infamous SPI-B document ‘Options for increasing adherence to social distancing measures‘ published on March 22nd 2020 to increase the level of personal threat felt by the complacent, my second significant concern was the astonishing idea that the authors could “leave aside the ethical and political dimensions of this argument”. How can psychologists leave aside the ethical dimensions of using fear, whether for an article or advising Government and drafting the plans in the first place?

Professor Ellen Townsend and I decided to write a response to challenge these claims. We could not write a rapid response in the BMJ since we would have been limited to 600 words. Hence, 13 months later, a more substantive peer-reviewed article — a form of ‘response’ — has been published in Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy with co-authors Professors Gemma Ahearne, Robert Dingwall, Lucy Easthope and Michael Riordan, ‘The Three Rs of Fear Messaging in a Global Pandemic: Recommendations, Ramifications and Remediation‘.

In our paper we lay out the evidence that SPI-B did support the use of fear messaging, contrary to existing psychological and disaster planning literature. Furthermore, it was never possible to simply target the ‘complacent’, who were not defined and were in fact doing a reasonable job of assessing their own risk. Consequently, the entire population was subject to fear messaging, with all of its damaging consequences.

SPI-B did recommend the use of fear. Not only that, even if it had not recommended fear, note that it did not criticise the Government’s campaign of fear in any of its members’ frequent turns in the media spotlight. The committee lay the ethical dimensions to one side. Psychologists actively proposing the use of fear should not leave aside ethics. Indeed, they are bound by ethical codes of conduct. If they disagreed with such fear messaging they had many opportunities — as well as arguably moral and professional obligations — to object on public record to the mass evocation of fear and the ensuing harms. This is, in fact, why some SPI-B advisers broke cover to speak with me for my book research.

On January 6th 2021, retired NHS psychologist Dr. Gary Sidley wrote to the British Psychological Society (BPS) about the unethical use of strategies to gain mass compliance, including fear, scapegoating and covert nudging.

One of the ‘Statement of Values’ in the BPS Code of Ethics & Conduct (2018) (12), stipulates:

3.1 Psychologists value the dignity and worth of all persons, with sensitivity to the dynamics of perceived authority or influence over persons and peoples and with particular regard to people’s rights.

In applying these values, Psychologists should consider: … consent … self-determination.

3.3 Psychologists value their responsibilities … to the general public … including the avoidance of harm and the prevention of misuse or abuse of their contribution to society.

The use of fear causes harms. Even if lives are potentially saved by calibrating the risk of death where people have underestimated risk, there are harms to mental and physical health by amplifying fear. Furthermore, the British public had an exaggerated understanding of the risks. One survey in July 2020 found that the British public thought 6-7% of the population had died from coronavirus, which was around 100 times the actual death rate.

So, given the negative ramifications, issues with effectiveness and ethical concerns, why did the SPI-B advisors recommend raising the perceived threat among the ‘complacent’? This is not addressed in the article by Reicher et al.

Among many reasons, realistically, one could be that the fears felt by psychologists themselves advising the Government affected the quality of professional advice. One SPI-B advisor told me under cover of anonymity for A State of Fear that “psychologists tend to be more on the neurotic end of the spectrum”.

Sometimes this was all too obvious. Implying that Boris Johnson should delay the road map, SPI-B’s Professor Stephen Reicher tweeted in the run-up to the original Freedom Day of June 21st:

What sort of sign does he want? The Thames turned to blood? A plague of frogs? Writing on the wall that spells out ‘we are all doomed if you don’t stop your dithering’? But seriously, what sort of sign does he want?

No Biblical scale event followed Freedom Day.

Also in June 2021, Professor Susan Michie argued on Channel 5 that face coverings and social distancing measures should continue “forever”, comparing the behaviours to routine ones such as wearing seat belts and picking up dog poo. Face coverings make little to no difference to the spread of respiratory flu-like illnesses and COVID-19 according to this Cochrane review. The idea that we might wear them forever despite the many harms, but for little to no benefit is deranged.

Later in December 2021, amidst calls that another lockdown was needed, Professor Robert West, tweeted:

It is now a near certainty that the U.K. will be seeing a hospitalisation rate that massively exceeds the capacity of the NHS. Many thousands of people have been condemned to death by the Conservative Government.

In fact, the U.K. never came close to SAGE’s projected deaths of 600 to 6,000 a day, or exceeding NHS capacity.

These professors should not be singled out for experiencing fear during the pandemic, nor for performing something of a volte face about the strategies deployed to combat COVID-19. Incidences such as these are now coming hard and fast. Just this week, in a notably mind-blowing example of amnesia, presenter Susanne Reid confessed on ITV’s Good Morning Britain, “Looking back I think we failed our children during the pandemic”. (This was in response to the news that school closures during COVID-19 mean that GCSE results will be poorer in England well into the 2030s. The impact on education and as well as mental health was predicted by experts at the time.) Yet at the time, GMB asked viewers a number of times whether schools should lock down, posing polls on Twitter, and interviewing Zero Covid fanatics who pushed this totally destructive idea. (Remember we don’t have Zero Covid now, and we never will. If they had had their way, we’d still be locked down, masked up, and schools closed.)

Over the coming years, expect to hear many more people say they never supported Zero Covid, lockdowns, the Rule of Six, school closures, tiers, cancelling Christmas or face coverings.

During the period of the COVID-19 Inquiry, no one should be immune from self-reflection. Those involved in advising Government should consider their ethics, biases and cognitive dissonance.

This article was first published on Laura’s Substack page the Free Mind. Subscribe here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

What does the British Psychological Society have to say about this unethical behaviour?

ISTR that they said it was ethical. I suppose it is they who decide what is ethical or not ethical. If not, who?

Nothing probably; they’re psychologists after all. Note the quote in the article: “psychologists tend to be more on the neurotic end of the spectrum”

Reminds me of the old joke that Psychiatrists tend to be nuttier than their patients.

“psychologists tend to be more on the neurotic end of the spectrum”

Well, who would have thought that?

Psychology…about as much of a science as virology or climate changeology.

Well, the acts played out over the Covid era and since show psychology to be an exact science when applied under certain conditions to the masses. It can’t guarantee a 100% uptake, but it can guarantee a large majority can have their behaviour controlled via a coordinated psychological attack. I’d argue that the very pinnacle of scientific achievement is to control human behaviour through psychological manipulation that hides the mechanisms being employed. Once that is achieved, which it largely is already, all future ‘science’ is a product of that science.

Good point and will be interesting to see how strong the nut zero propaganda will be when the electricity fails and petrol and diesel is no longer available to buy.

A scientific achievement?

It would be an achievement, of sorts, and Scientific knowledge might have been employed, but it isn’t a scientific achievement: Science is a mode of enquiry. What you do with the knowledge gained is up to the individual.

I’ve known many doctors socially. They tend to be the most anxious of parents. I’ve always put this down to them seeing sick kids all days. No surprise that they see the exception as the rule.

Selective memory syndrome just means many in the media and politicians are now lying. However the evidence is on our screens and they should be exposed. Keir Starmer said it would be a catastrophe to open up in July 2021. Nothing of the sort happened. The economy and our children would have suffered even more if he had been PM.

Not only do we have a shockingly poor government, we have a non-existent opposition.

They prefer to bicker and score silly points off one another. Lockdown parties? Second homes? How about Lockdown was one of the greatest evils ever visited on the world? Nope, not a whimper.

Labour had an open goal during lockdown: they could have bemoaned school closures, the killing of small businesses everywhere, the destruction of workers’ rights and much more.

Instead they were not only complicit, but actively egging the government on.

I always knew we were ‘led’ by donkeys, but it took 2020 for me to realise quite how bad our ‘leaders’ have become. I mean it’s clearly been bad for a while but it was fairly low-key before and it took the so-called ’emergency’ to bring the extent of the rot fully into focus for me.

I felt, and still feel, so much anger that the basic mechanisms of government let us down but, although a painful realisation and a rude awakening, I’m pleased to have woken up to the scam.

There’s a monoculture within the political bubble: mostly graduates from the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, with very few with Business experience. History and PPE appear to a favorite within the Dept. of Energy And ‘Business Experience’ doesn’t mean being a consultant, with magical powers from having the backing of a big firm.

This medical agenda has been supported by an organisation, created in the image of a socialist state, (in 1948), turns to victimhood when it suits them, and protects the pharmaceutical industry from criticism.

I think we sshould consider prosecuting them or at the very least lose their lucrative jobs. They are all cupable and should be shown up for the charlatans that they are, irrespective of who they are.

Great image in the article. The Rona Fascism was fuelled by fake tests, fake dead counts and endless fear porn. Governments paid the Fake News to scream of imminent doom and killing granny if you weren’t diapered, locked down and stabbinated. Zero science. 100% Fascism.

Seconded. That shows exactly 180 propaganda posters churned out by the Third Reich of the pandemic years. It is little wonder that the UK government – specifically what is now the UK Health Security Agency – during those years became by far Britain’s largest advertiser! This was in effect most people’s experience of the pandemic – that of fearmongering, news, propaganda, being personally restricted, i.e. most of it happened on the other side of a TV screen. Most of what we experienced was the response to the pandemic, not the pandemic itself. Me personally? The business I work for closed for two years before finally being sold to new owners, lots of crap in the media, talk amongst friends and family about the pandemic (always external to any of our experiences), followed by a jab in the arm that did nothing useful.

Games within games within games. I’m not playing. All a distraction to keep the masses subdued and confused. Keeping the masses quiet long enough to stealthily enact global change is key. And providing sites where people who know can vent their anger by changing pixels on a screen rather than overthrowing their government is absolutely crucial…. I suppose I am unwittingly playing after all.

“We experts all knew the government was ignoring our advice and promoting fear, but we didn’t like to say anything in public because we were scared it would affect mask-wearing, lockdown behaviour and vaccine compliance.”

Toadies.

Yes they should. They should be figuratively pilloried in mainstream and social media. These so called experts failed in their duty of care.

They should not be exonerated just because a bunch of other people are similarly blameworthy. Expose them all.

Never forget.

Updated to add: Nobody should defend these people by suggesting they were no more or less bad than many others. That’s not what we should expect of experts.

It’s exactly what we should expect of experts.

Experts, as my dad says, are people who know everything about nothing.

‘Ex’ something that has been,

‘spert’ a drip under pressure

It’s the TV experts that need to be singled out, and their supporters. There were plenty of knowledgeable people that ‘got it right’, but they weren’t allowed on the airwaves.

The BBC have played an active part in the Climate Farce, the NET Zero Scam and the Global Medical Intervention Disaster.

I haven’t gotten round to watching this documentary yet, but Jacqui Deevoy did a great job with her last film on the outright murder of vulnerable members of the public by the medical system/government. If anyone wishes to give a quick review after they’ve watched it that’d be much appreciated;

”Playing God is a profoundly moving documentary that dives into the heart-wrenching journeys of families who have lost their loved ones to end-of-life drugs.

Jacqui Deevoy, co-producer and presenter of the Iconic film A Good Death?, has teamed up with award-winning directors Naeem and Ash Mahmood and co-producer Phil Graham to create this jaw-dropping exposé on medical democide in the UK over the last 50 years.”

https://www.ukcolumn.org/video/playing-god

‘Those involved in advising Government should consider their ethics, biases and cognitive dissonance.’

And

Those advising the Government should add up all their qualifications and then ask themselves how such a bunch of over-qualified pompous stuffed shirts could be so unbelievably dim and incompetent…..

Let us never forget that we were all told by one of the world’s foremost coronavirus experts, actually in China, on 06 February 2020

‘People are saying a 2.2 to 2.4% fatality rate total. However recent information is very worthy – if you look at the cases outside of China the mortality rate is <1%. [Only 2 fatalities outside of mainland China]. 2 potential reasons 1) either china’s healthcare isn’t as good – that’s probably not the case 2) What is probably right is that just as with SARS there’s probably much stricter guidelines in mainland China for a case to be considered positive. So the 20,000 cases in China is probably only the severe cases; the folks that actually went to the hospital and got tested. The Chinese healthcare system is very overwhelmed with all the tests going through. So my thinking is this is actually not as severe a disease as is being suggested. The fatality rate is probably only 0.8%-1%. There’s a vast underreporting of cases in China. Compared to Sars and Mers we are talking about a coronavirus that has a mortality rate of 8 to 10 times less deadly to Sars to Mers. So a correct comparison is not Sars or Mers but a severe cold. Basically this is a severe form of the cold.’ Prof John Nicholls, Univ. of Hong Kong

If we could spot that and publish it on here in Lockdown Sceptics not long after that, why couldn’t they get the hang of it?

They should have resigned, to a man/woman/whathaveyou….oh for heavens sake!

They were following an agenda.

This is disgusting. Their tactics and manipulation plain for all to see.

”‘The world will not be destroyed by those who do evil, but by those who watch them without doing anything.” A. Einstein.

”This is some next level programming.

How many of you had even heard of the medical term Myocarditis prior to the experimental mRNA Injections?

Answer – not many – now commercials warning about kids contracting this heart scarring affliction are being aired on TV.

Insane.”

https://twitter.com/BGatesIsaPyscho/status/1783824715288572314

Re: “Professor Ellen Townsend and I decided to write a response to challenge these claims. We could not write a rapid response in the BMJ since we would have been limited to 600 words.”

Why couldn’t you write a succinct BMJ rapid response at the time?

A pithy response at the time would have been useful.

I had a BMJ rapid response published in March 2020, and reckon it holds up pretty well. If only medical and scientific establishment insiders had piped up with something similar at the time… But of course very few were equipped to challenge the blessed ‘Church of Vaccination’.

BMJ Rapid Response, 25 March 2020: https://www.bmj.com/content/368/bmj.m1089/rr-6

The same tactics are used around the ‘climate change emergency’ and people have continued to believe that twaddle for decades.

Yes and what’s more 80% of people would still lockdown wear masks and do all the other nonsense once again if /when the government dictates. I say this as talking to friends and family they still haven’t really “got it”. Sad and dangerous but true.

Covid psychological manipulation unpacked here too: https://youtu.be/4Iqa4CoMciU?si=L2Od-gJRaImpqvyj