The recent autumn and winter months have seen Britain beset by more than the usual number of storms, and more than average amount of rainfall. For most of us, this has been merely unpleasant weather, but it has seemingly caused rivers to breach their banks and put much farmland under water. This is a real problem in its own right. Predictably, now the waters are receding, adherents of green ideology are turning the farming drama into the climate crisis, with talk of “failed harvests” and predictions of our imminent hunger. But where is the evidence?

The Guardian, as we would expect, has been leading the alarmist chorus. “The U.K. faces food shortages and price rises as extreme weather linked to climate breakdown causes low yields on farms locally and abroad,” it proclaimed, adding that “scientists have said this is just the beginning of shocks to the food supply chain caused by climate breakdown”. “I wish people understood the urgent climate threat to our near-term food security,” mourned Associate Professor of Environmental Change at Leiden University in the Netherlands to the newspaper.

Citing his experiences as a carrot farmer, Extinction Rebellion (XR) co-founder Roger Hallam declared on X that, “I know what is going to happen – not because of these particularly bad years, but because of the speed at which things are getting worse now.” Only “urgent revolution” can save us. And this in a nutshell is what the entire green movement has long been warning us of – extreme weather that will force us into hunger, which will drive us into political extremism and social breakdown and the end of civilisation. So are these floods a warning from Gaia that she made no covenant with us, unlike that other God, and that clouds stand ready to unleash her revenge on us for our SUV sins? Are these greens latter-day Noahs, or just a ship of fools?

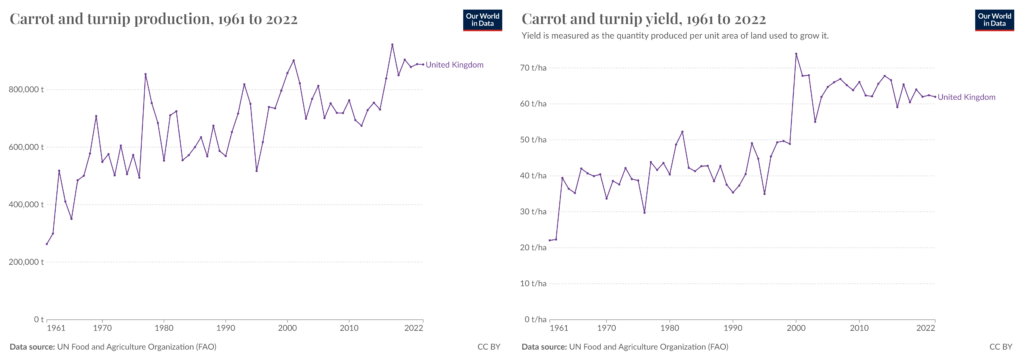

The problem for Hallam is that carrot production in the U.K. shows very little sign of sensitivity to climate change. Since the 1950s, carrot and turnip production has quadrupled. More significantly, yield per hectare – the indicator which is more sensitive to climate and weather – has more than tripled. If Britain was experiencing a climate-related carrot crisis, we would see this indicator plunge, rather than rise. Consequently, and contrary to fears about price rises, supermarkets are selling a kilo of British-grown carrots for 65p. ‘Wonky’ or ‘imperfect’ carrots are being sold at 45p/Kg. The struggle for carrot farmers may therefore be less high water than low prices for their products.

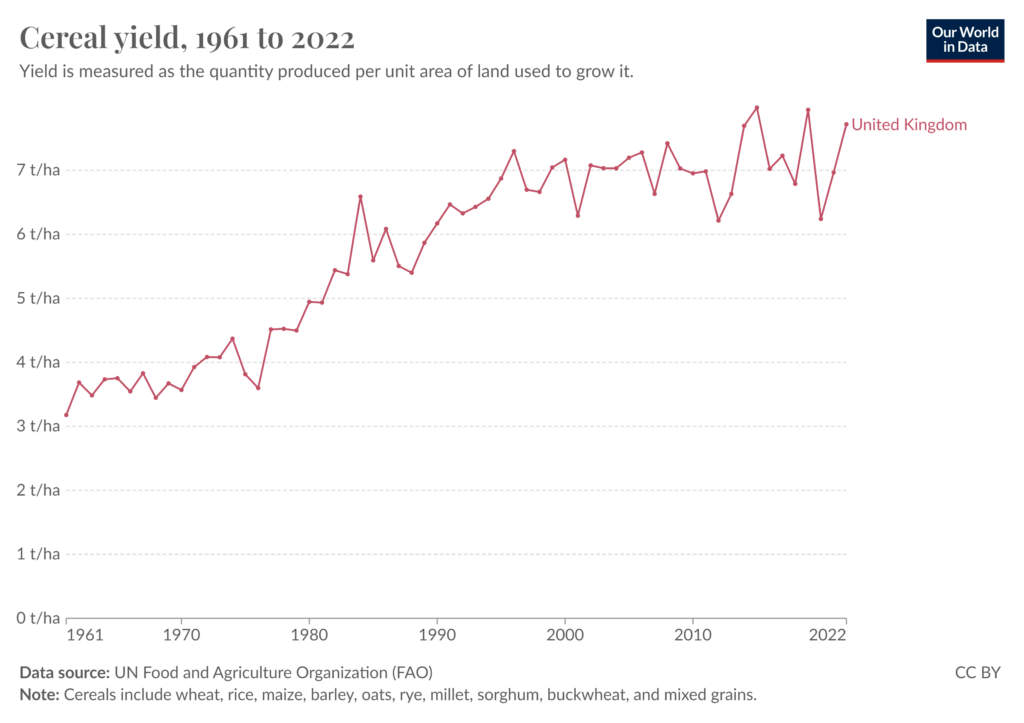

And the same story is revealed in UN data for nearly all British-grown vegetables. Inspection of the data reveals nothing resembling a pattern of climate change for the yield of wheat, oats, and cereals in general, onions, apples and pears, dry peas and other pulses, plums, potatoes and other roots and tubers, rapeseed, raspberries and strawberries, sugar beet and tomatoes. The only reductions in yield relate to the production of cauliflower and broccoli, and green peas. However, given that these data are significant outliers, we can for the moment assume that other reasons, perhaps economic or regulatory, better account for apparent declines in yield. Meanwhile, there is plenty of evidence in the U.K. and beyond that the era of global warming – or climate crisis – has been an era of bumper harvests.

Caution is required here. The point that sceptics rightly make to alarmists is that weather is not climate. It would be foolish to say that just because there exists no climate signal in agricultural production statistics, there is no evidence of weather affecting farming. There is.

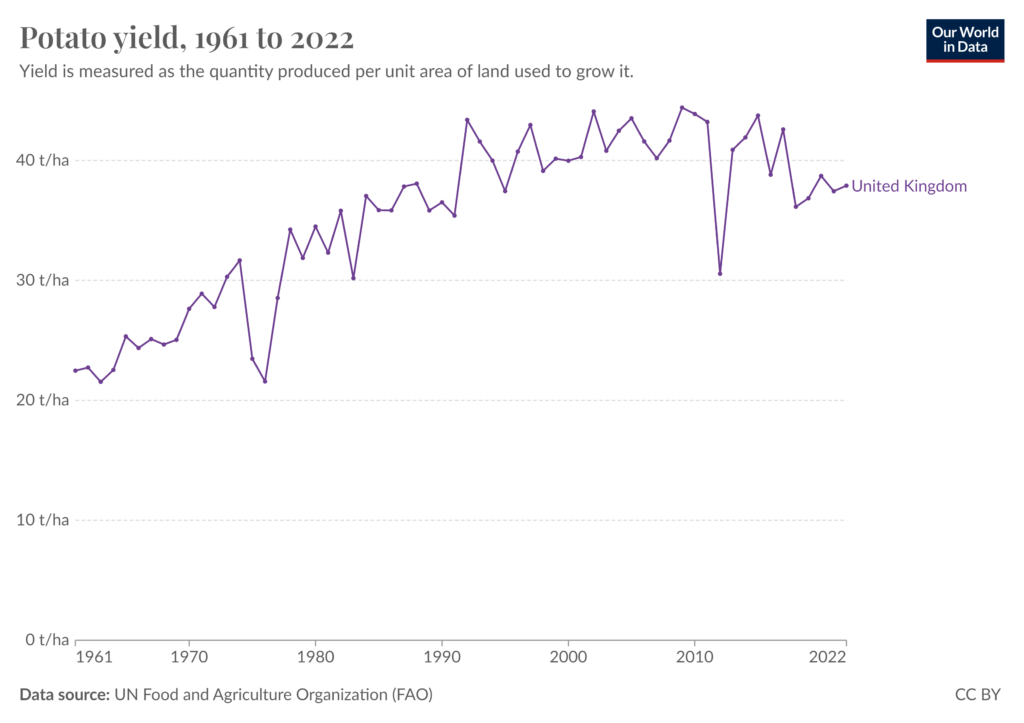

In the 60 years of data about the production of potatoes in the U.K. there have been two unquestionable impacts of weather. The first occurred in the drought and heat years of 1975 and ’76. The second occurred in the washout year of 2012, though not, curiously, in the non-summer of 2008 and the ‘barbecue summer’ of 2009, which left the U.K. Met Office with egg on its face. However, the consequences of these disappointing years for society more broadly is very far from famine. Whereas potato famers produced 100kg of their crop per person in the U.K. in 2011, in 2012 this fell to 72Kg, the difference being made up by imports, mostly the following year. Chips and crisps may have cost slightly more, but nobody went hungry. And imports are perhaps the explanation for the gradual decline of overall production of the crop, too. Despite the ‘crisis’, potatoes are retailing for as little as 75p/kg in supermarkets.

It remains to be seen whether or not, and to what extent, recent weather events have affected agricultural production statistics. Nonetheless, farmers across the U.K. are reporting real problems. A mostly sober article in January’s Farmer’s Guide features the experiences of farmers from Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Essex and Lincolnshire following the deluge delivered by Storm Henk, leaving in some places the “highest flood level in more than 70 years”. Again, these are reports of serious problems that can ruin a farm. But the climate change narrative distracts from this necessary discussion. The article concludes with the words of Dr. Jonathan Clarke from the Institute for Global Sustainable Development at the University of Warwick, who claims that “there is an urgent need to consider how our society can become more resilient to the worst effects of a changing climate”. But weather conditions the same as we experienced 70 years ago are not evidence of an “urgent need” as much as they are a reminder of weather being a constant problem, and therefore of academics’ and scientists’ recent departure from both reality and historical fact.

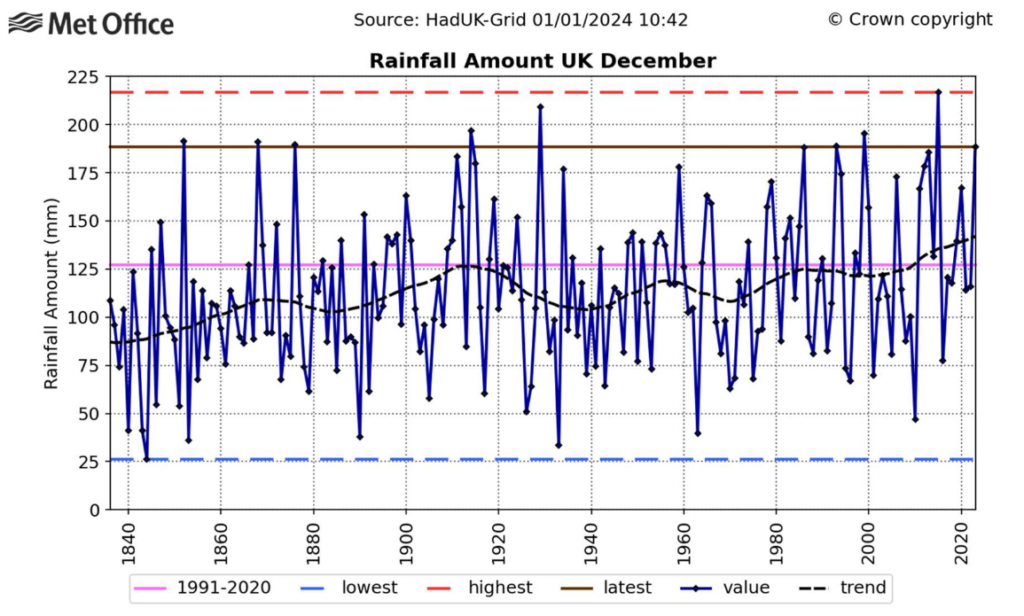

So what has been the signal from weather? The Met Office’s data show that, for the country as a whole, March, February, December, October and September of last year brought significantly more than average rainfall. In a series of monthly data spanning 188 years, those months respectively were the 19th, 4th, 11th, 8th, and 63rd wettest of those months for England, and the 31st, 11th, 9th, 7th, and 32nd for the U.K. as a whole. Nasty for all of us, and especially difficult for famers. But does it even stand as evidence of “extreme weather”, as the Guardian claims, let alone man-made climate change-induced “extreme weather”, requiring “urgent” interventions to prevent it getting worse? Isn’t it just… you know… weather?

The worst of those months for the U.K. – the ninth wettest December – can be seen in its historical context. The Met Office provides a running average, which would seem to stand as an approximation of ‘climate change’. But despite that moving trendline, there were plenty of comparable Decembers in the mid to late 19th Century, and in the early and late 20th Century.

Moreover, the inter-annual variation of December rainfall spans nearly an entire order of magnitude, from 25mm to just under 225mm. The averaging of such noisy data does not and cannot reveal any underlying changing reality because it does not and cannot tell us anything useful – the trend is a phantom. Even if we were to follow on the Guardian’s and scientists’ injunction to eliminate emissions from fossil fuels, farmers would be no better protected from either drought or deluge. Moreover, if those trends were to be interpreted as probabilistic forecasts on which decisions are based, farmers would go bust in short order, because gambling on either more or less rain is guaranteed to produce a busted flush.

Farmers are not automata whose cyclic programming requires the same conditions each year. Farming is not a process with narrow operating thresholds that have been exceeded. Farming is an art, which requires careful judgement based on experience acquired by generations of farmers developing expertise in coping with hostile circumstances, including both different weather and market conditions.

The evidence clearly shows that continuous and increasing supplies of food are produced despite radical interannual monthly, seasonal and yearly shifts in weather, regardless of any semblance of trends in those variations. It has no doubt been a wet winter and spring. And this wetness may well have an effect on this year’s harvests. But the notion that this has anything to do with climate change, as per the framing of the Guardian‘s radical activists and equally ideologically-driven scientists, puts ideology before reality.

Many farmers have taken to social media to show videos of their submerged farms. And this speaks to the absurdity of framing first-order problems like flooding as extremely abstract climate-related phenomena, for which there exist little if any evidence. The extant raw data, which span 188 years, tell us all that we need to know: some months there is very little rain, and these months may coincide; some months there is a great deal more rain, and likewise this can add up to create a backlog that needs to be drained. That is the full extent of the data that policymakers require to develop drought and flood mitigation strategies, and those parameters are completely unchanged by climate change, if any climate metrics can be squeezed out of the data at all.

In other words, we already know how dry it can be, and we already know how wet it can be. Therefore, we know what we need to do to ensure that there is sufficient water in drought and sufficient drainage in times of excess rainfall. We know, therefore, how badly politicians are already failing at their job. Their preferences for saving us with policies that ban cars and domestic gas boilers, tax flights and cover agricultural land with turbines and solar panels will not change these parameters. And by pushing up the prices of energy and feedstocks, it will likely create an agricultural crisis where none needs to exist. Climate change is a massive distraction from our real and present problems.

Subscribe to Ben Pile’s The Net Zero Scandal Substack here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Hallam says ————–“I know what is going to happen – not because of these particularly bad years, but because of the speed at which things are getting worse now.” Only “urgent revolution” can save us”——————No Mr Hallem you don’t know what is going to happen at all. You are just another brainwashed dreamer. There are no scientists or experts or computer modellers that know what the climate is going to do and neither do you? You will also find that nothing is getting worse and at speed. There is no increase in the frequency or intensity of any type of weather event anywhere in the world. Not storms, not floods, not droughts, not wild fires —NOTHING. ——You are calling for “revolution” and you need to be arrested for inciting violence.

From Nature magazine, ref the outcome of the Hunga Tonga eruption in 2022, in words written for the man on the Clapham omnibus to understand: “ we show evidence for an unprecedented increase in the global stratospheric water mass by 13% relative to climatological levels”

13% more is one helluva lot of water up there!

I tell everyone who complains about the rainfall about the Hunga Tonga eruption and the water vapour in the stratosphere What goes up must come down eventually and the water is going to replenish the underground aquifers so that is a positive. Usually silences them.

There’s a marked increase in hysterical articles about upcoming doom because of climate change. Eg, yesterday’s example of the BBC making a fool of itself by reporting that it’s hot in the Sahara and that some people over 60 DIE, as if this had never happened before. This is really all just about publishing the right terms (Climate change! Heat waves!! DEATH!!!) over and over again to start nudging people for the planned big climax in summer, presumably August, when one can reasonably expect some nice weather even in the UK. Heat records will certainly also be broken somewhere inside the afterburners of starting jets and WE ARE ALL GOING TO DIE!!!

I think that’s a good sign: These people know that they’ve technically run off the cliff and are desparately trying to stave off falling down by roadrunner-style air treading.

Anyone ever known a farmer saying the weather is just right? Me neither. As Ben Pile says, their biggest problems are the imposition of runaway external costs, being shafted by supermarket pricing and the burden of ever-increasing bureaucracy.

Whatever the weather is, everybody’s always complaining about it. I think that’s really the sole original raison d’etre of using language for communication: People desiring to complain about the weather to someone.

I agree that only urgent revolution can save us now — we must urgently do away with all these “Work? Not for me!” Hallams trying to engineer our doom for their personal gain.

It comes to something, when I trust what I hear from a former motoring journalist and Amazon entertainment show host turned farmer (Jeremy Clarkson), than all the pseudo science peddled on the mainstream news

Just come back from the States and a few people mentioned Clarkson – they love him and his show on farming. I recall reading here a few weeks back that his programme is also popular amongst European farmers.

“create an agricultural crisis where none needs to exist.”

That is exactly what is taking place all pushed by the likes of Fishy and Co acting on orders from the Davos Deviants. We are being herded in to a food crisis the sole purpose of which is to confirm that there is something of a “climate crisis.” Nothing but grotesque lies and nonsense but with a seriously evil intent behind it all.

The “Crisis” is the Liberal Progressive Crisis that has spread all over the western world. It has 5 main symptoms. —Equality Diversity Race Gender and Climate. ——Anyone suffering from any of those should not see their doctor, because (1) There is little chance of an appointment unless you just arrived here on a boat and (2) The Surgery will likely be signed up to the Liberal Progressive Agenda and they will only tell you that “Your phone call is important to us” and that you should “Treat our staff with dignity and respect” as if we were all a shower of screaming pig ignorant banshees. ——–No don’t see your doctor. Instead just sign up to the Daily Sceptic and relieve yourself of those symptoms by passing comment here. And if that doesn’t work come back and see me in a fortnight.

Some food for thought about these issues in America by taking a look at one state, North Carolina, and having a conversation with farmers: https://bit.ly/49mHN6y