Illness is identified by taking a history, examining symptoms and signs, and often by taking some tests.

Many of us seem unwell as much testing is happening – roughly 50 million diagnostic tests, 500 million biochemistry and 130 million haematology tests are performed annually in the NHS. In the U.S., it’s another order of scale, with 14 billion laboratory tests ordered annually. Testing is also on the increase: in primary care, it increased by 8.5% per year between 2000 and 2015 across all ages. The proportion having more than one test has also increased significantly. However, there are wide variations in testing, which is unlikely to be explained by clinical need.

The CDC reports that 70% of medical decisions depend on laboratory test results, but what happens when these decisions do not benefit patients or would never have caused any symptoms or problems?

Overdiagnosis transforms people into patients unnecessarily by identifying problems that were never going to cause harm or by medicalising ordinary life experiences through expanded definitions of diseases.

As an example, the most extensive study to date of the Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) blood test to screen for prostate cancer found it only had a negligible impact on reducing deaths. Still, it led to overdiagnosis and missed the early detection of some aggressive cancers.

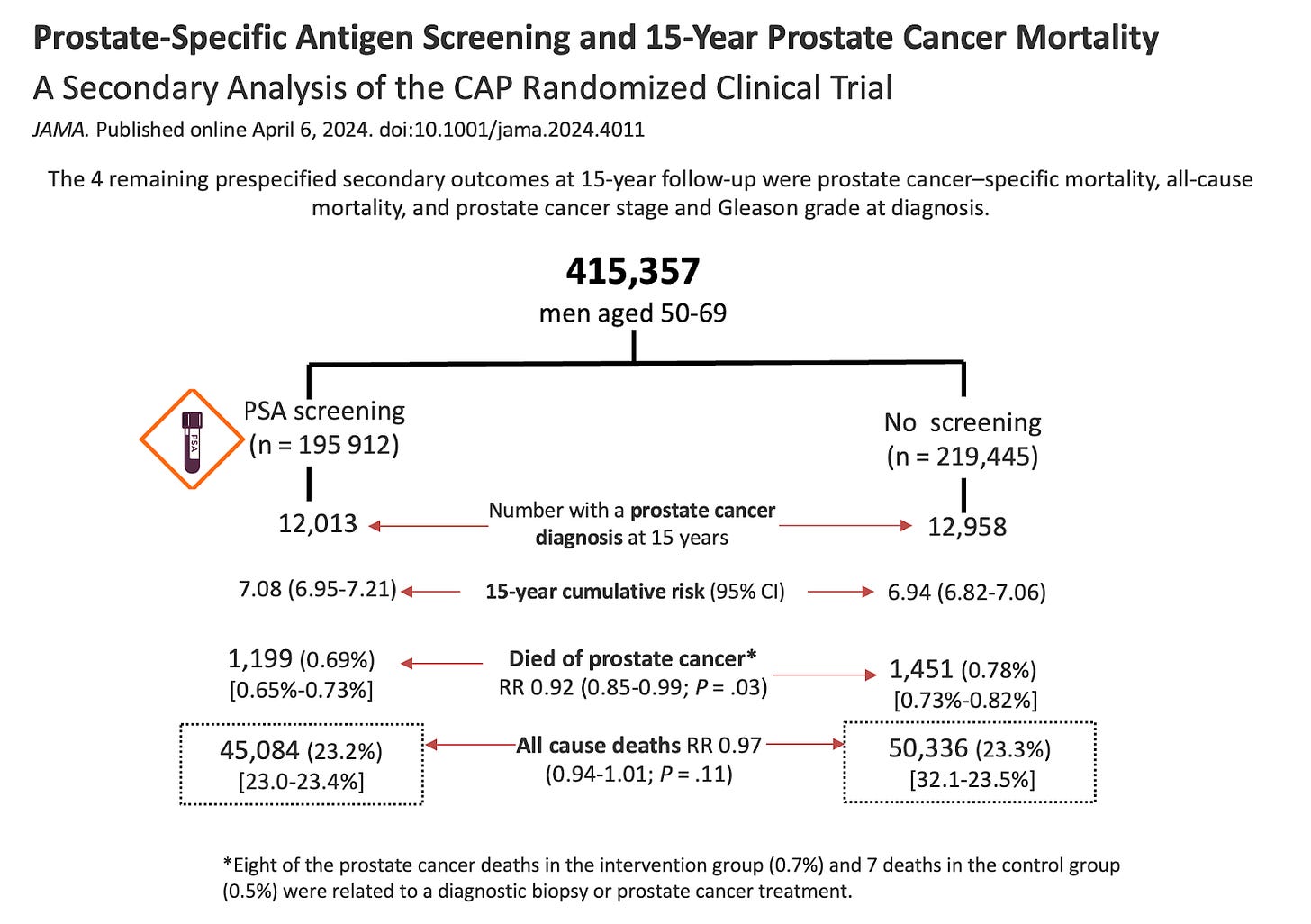

The trial included 415,357 men between the ages of 50 and 69. They were randomly assigned to a single invitation for PSA screening or a control group without PSA screening. The participants were followed up for a median of 15 years.

So, while a single invitation for PSA screening reduced prostate cancer deaths by a tiny amount, roughly one in 1000 men tested, it had no impact on all-cause deaths, which is the outcome you are concerned about.

PSA screening did increase the detection of low-grade and localised disease but not intermediate, high-grade or distally advanced tumours. As a consequence, about one in six cancers were over-diagnosed. These men went on to have invasive treatments they didn’t need, while the test failed to spot aggressive cancers requiring intervention – creating stress and worry for no reason.

You might expect all this extra testing to translate into better outcomes. Yet, medical practices with the highest PSA rates do not see reduced prostate cancer mortality. However, they do see increases in the number of downstream diagnostic and surgical procedures with potentially harmful consequences.

A slight reduction in prostate cancer deaths weighed against the lack of all-cause mortality and overdiagnosis that comes with all the worry and stress means the benefits of testing often do not outweigh the potential harms.

Over-detection and over-definition of diseases are major causes of over-diagnoses, which ultimately cause more harm than benefit. When it comes to testing, more is not always better.

Dr. Carl Heneghan is the Oxford Professor of Evidence Based Medicine and Dr. Tom Jefferson is an epidemiologist based in Rome who works with Professor Heneghan on the Cochrane Collaboration. This article was first published on their Substack, Trust The Evidence, which you can subscribe to here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

My mother was quite fearful of doctors – which is a trait that I have inherited. My 3 sisters and I are all in our sixties, but they are quite comfortable with doctors and medical treatments and although healthy, are frequent visitors to their local sugeries for check ups and flu and covid jabs.

They find my attitude to doctors bizarre – I have seen a doctor just 6 times since the 1960’s and have never taken flu or covid jabs (3 of the visits were for earache requiring antibiotics, one for allergy advice and the other 2 for minor physical problems). They are always mithering me to see the doctor and have various health checks and measurements taken. I don’t succomb to their harassment, but do take some vitamin supplements and make food and exercise choices that I feel will benefit me.

I don’t endorse my attitude to doctors or think that I will live a longer or healthier life because of it, nor do I recommend it to others But it has served me well so far and it is MY CHOICE. The medical “mafia’s” response to covid – masking and social distancing (with no convincing evidence for it), jabs (without proper trials) and many of them screaming to make the vaccines compulsory (I’m sure they weren’t influenced by their £15-a-shot payments) convinced me that my aversion to medical “professionals” is not necessarily a poor choice.

Same. I literally need to be at deaths door to see a Dr.

Same here. I used to consider my needle phobia to be a problem which had to be overcome (I’ve had a lot of hypnotherapy) but after the events of the last 3 years I look upon it differently.

I take care of my own health. I’m now mid-60s; slim, fit, healthy – I take several health supplements but no pharmaceutical products whatsoever, apart from a very occasional paracetamol.

My sister, two years older, is constantly going to the doctor and has several health issues. But apparently I’m the “idiot” for refusing to get the ‘flu or covid jabs.

The broad title and the one example in the article don’t match. Are there any other cancer screenings that don’t reduce cancer deaths? I’ve seen articles indicating that colonoscopies don’t decrease deaths from colon cancer–the patient just knows he has the cancer for a longer period of time. Also, if cancer screenings don’t decrease deaths, then missed cancer screenings from 2020 to 2022 aren’t the reason for increases in cancer diagnoses seen worldwide.

Those in the private sector evidently benefit financially by promoting PSA, if you watch GBN much. At least it’s a source of income for GBN.

There is a lot of money to be made from testing.

Just ask those that minted it with the covid PCR tests.

The medical profession has been captured by the pharma medical complex, so I expect testing of diseases to increase, not decrease.

They might even get the WHO to make all manner of tests compulsory…

PSA is well known to be a doubtful test. On retirement of my GP the new GP suggested I should stop doing it. However as my results had for years been consistent I have preferred to continue it as a sudden large change might in my case be indicative of something requiring further consideration. The well known doubts on this particular test do not necessarily mean that all other screening is useless.

Two friends of mine left it too long to have a PSA test which would possibly have saved their lives. When they finally did decide to have the test, followed by a biopsy it showed advanced aggressive cancer.

This is the second recent article on PSA testing. It is quite interesting but I don’t understand why they are published here. The medical establishment is well aware of the problems and PSA screening is not NHS policy. (although the test may be useful in specific contexts)

NHS health checks can be quite worrying.

My doctor, who I didn’t see, said my latest results were satisfactory.

The nurse, who I did see, wanted, surprise, surprise, to put me on statins.

Thresholds for blood pressure, blood/sugar levels, are changed without any publicity so that more patients become described as ‘pre-diabetic’ or with ‘borderline’ blood pressure.

Consequently I very much welcome these articles by Carl Heneghan et al on here as providing useful perspective.

Why are they on here? They provide useful perspective and promote healthy skepticism, precisely the aim of this website.

Good post. I am in full agreement.

FWIW stay away from statins they are dangerous, useless and a con. No surprises there then.

Thanks. Quite so.

I’ve been posting about the perils of statins for some time.

‘….potential side effects of statins include fatigue, erectile dysfunction, memory loss, cognitive defects, ALS-like symptoms, aggression, irritability, polyneuropathy, peripheral neuropathy, muscle cramps and muscle weakness.’

https://dynamicchiropractic.com/article/55781-statins-and-cardiovascular-disease-not-as-protective-as-were-led-to-believe

‘In contrast to the current belief that cholesterol reduction with statins decreases atherosclerosis, we present a perspective that statins may be causative in coronary artery calcification and can function as mitochondrial toxins that impair muscle function in the heart and blood vessels through the depletion of coenzyme Q and ‘heme A’, and thereby ATP generation… Thus, the epidemic of heart failure and atherosclerosis that plagues the modern world may paradoxically be aggravated by the pervasive use of statin drugs. We propose that current statin treatment guidelines be critically reevaluated.’

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25655639/

‘A controversial new study found that high cholesterol does not shorten life span and that statins are essentially a “waste of time,” according to one of the researchers. Previous studies have linked statins with an increased risk of diabetes.

The study reviewed research of almost 70,000 people and found that elevated levels of “bad cholesterol” did not raise the risk of early death from cardiovascular disease in people over 60.

The authors called for statin guidelines to be reviewed, claiming the benefits of statins are “exaggerated.”

Not only did the study find no link between high cholesterol and early death, it also found that people with high “bad” cholesterol (low-density lipoprotein, or LDL) actually lived longer and had fewer incidences of heart disease.

The co-author and vascular surgeon went on to say that cholesterol is vital for preventing cancer, muscle pain, infection, and other health disorders in older people. He said that statins are a “waste of time” for lowering cholesterol and that lifestyle changes are more effective for improving cardiovascular health.’

Personally I found both articles very interesting.

To me the whole point of being a sceptic is taking the time to question everything by trying to seek out and evaluate the evidence behind any idea from as near as first principles as you can get. The alternative is to rely on ‘experts’ who generally should be ignored because they are really only people appointed by their funders (so not the real experts in their field) who are willing to do anything to support the position taken by their funders. Generally speaking expertise and ideas shouldn’t be ignored but ‘experts’ should. Both articles help with this.

If on (what seems to be rare occasions these days!) the evidence points to an official policy being reasonable, then that doesn’t mean that sceptical enquiry hasn’t been useful and shouldn’t be reported here.

As an example let’s take a very basic initial look at the bowel cancer screening programme (through the FIT test) that has now been extended to 50-59 year olds. The first link they give as evidence for the screening is

Hewitson P and others. ‘Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update’. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2008: 103(6).

If you look at that, unfortunately you can’t access the full text without a subscription. But even in the results you see as well as reporting lower bowel cancer deaths they say

There was no difference in all-cause mortality (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.99-1.02) or all-cause mortality excluding CRC (RR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00-1.03).

There was also a UK study (from memory I think it was a randomised control trial in Nottingham) which seemed to show the same thing although it never seemed to quite say (from what I could access) whether all cause mortality was the same in those who had or hadn’t had the screening only that all cause mortality for specific causes other than CRC (colorectal cancer) was not statistically different.

So is there a possibility (even if it’s a small possibility) that this bowel cancer screening is also a waste of time because although there appears to be a reduction in bowel cancer mortality there is no obvious reduction in all cause mortality. On the surface removing polyps following screening that might become cancerous doesn’t seem unreasonable, but then again there can be dangers of overtreatment which might in some cases be unnecessary surgery. What does the evidence really show?

Clearly I’ve only looked at this on a very very cursory basis for the purposes of clarifying the starting point for scepticism on a particular topic. But I would love to see someone without conflicts of interest who has access to the full studies and time to evaluate them, show the evidence for and against bowel cancer screening. To me the NHS information on this topic is inadequate and hence should be subjected to sceptical enquiry. And if someone did that analysis that would make a good item to be reported on the daily sceptic whatever the outcome.

Fair enough if you find it interesting. I guess I see this site as “challenging the prevailing orthodoxy” which this article clearly isn’t. I suppose I am concerned that publishing the article might wrongly give the impression that the establishment is pushing tests on us which we don’t need for nefarious purposes and thus contribute to a lack of response to useful testing programmes.

The prevailing orthodoxy, particularly for prostate tests, is to have the test.

Two of my friends have told me to have the test, although I have no symptoms that would suggest I need such a test.

Both were pro covid vaccine, one is no longer with us having died from an eminently treatable cancer which suddenly accelerated.

I have always had faith in the medical profession until the mid 1990s or so. Since then, things seem to have gone downhill.

Any connection to Blair’s Britain? I think so.

The prevailing orthodoxy, particularly for prostate tests, is to have the test.

Whose orthodoxy and tests in what context? I would have thought official NHS guidance was as close to prevailing orthodoxy as you can get. Read it for yourself. This in the context of screening a healthy man with no symptoms.

Of course the test may be useful if you have other symptoms that suggest prostate cancer or if you follow a regime of repeated tests to monitor a trend. But you were right to ignore your friends’ advice. Don’t take the test unless someone expert explains why you are taking it and someone expert will interpret the results. Remember it is not a yes/no test. All men have some PSA in the blood – it is just that if you have prostate cancer the level may be raised – the more it is raised the greater the level of concern and a trend of rising levels is just as significant as the absolute value.

There is a great deal of promotion of testing going on:

‘The NHS teamed up with Prostate Cancer UK to deliver a six-week campaign from mid-February, urging men to use the charity’s online risk checker in a bid to reduce the shortfall in men starting prostate cancer treatment since the pandemic began.

The latest NHS figures show the campaign had an immediate impact as urological cancer referrals in March increased by more than a fifth (23%) compared to the previous month and are up by almost one third (30%) compared with the same month last year.’

https://www.england.nhs.uk/2022/05/checks-for-prostate-cancer-hit-all-time-high-on-back-of-nhs-and-charity-awareness-campaign/

‘The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in fewer people presenting to their GP and therefore a reduction in the number of referrals to hospital for further investigation. This meant an estimated shortfall across Surrey, Sussex and Frimley of 640 prostate first treatments between March 2020 – September 2021. (Source: COSD Rapid Cancer Registration Dataset)

To find those missing men, we worked with NHS partner and virtual hospital provider, Medefer, to pilot a new service in August 2022 to identify and offer non-invasive prostate tests to eligible males.’

https://surreyandsussexcanceralliance.nhs.uk/our-work/prevention-early-diagnosis/early-diagnosis-prostate-cancer

‘The next step towards a national prostate cancer screening programme is already underway, with the LIMIT trial being conducted with a much larger number of participants.’

https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/news/mri-scans-improve-prostate-cancer-diagnosis-screening-trial

That’s just a ten minute search…..

I think we are at cross purposes. I am talking about the PSA test. Your references are about other candidate tests. A test for prostate cancer with good specificity and sensitivity and low cost (in a broad sense of cost) would be a big leap forward.

(I think this is my last day of being able to comment without making another donation so I may not hbe able to continue the discussion tomorrow.)

So prostate cancer screening saves 1 in a thousand lives. Well I’m sure that one chap is very glad it saved his life. Other cancers are treated successfully when found by screening that would have had poorer outcomes if not treated at an earlier stage. The headline doesn’t make sense.

Not so: ‘…..it had no impact on all-cause deaths, which is the outcome you are concerned about.’

The individual simply died of something else within the same timeframe.

‘…….it had no impact on all-cause deaths, which is the outcome you are concerned about.

PSA screening did increase the detection of low-grade and localised disease but not intermediate, high-grade or distally advanced tumours. As a consequence, about one in six cancers were over-diagnosed. These men went on to have invasive treatments they didn’t need, while the test failed to spot aggressive cancers requiring intervention – creating stress and worry for no reason.

You might expect all this extra testing to translate into better outcomes. Yet, medical practices with the highest PSA rates do not see reduced prostate cancer mortality. However, they do see increases in the number of downstream diagnostic and surgical procedures with potentially harmful consequences.

A slight reduction in prostate cancer deaths weighed against the lack of all-cause mortality and over-diagnosis that comes with all the worry and stress means the benefits of testing often do not outweigh the potential harms.’

A few more questions about this. (I would like to address them to the authors but I am not going to pay £10 to ask one set of questions!).

The introduction seems to question the value of medical testing in general but then it rapidly moves on to the example of screening for prostate cancer. Other cancer screening programmes are more successful and testing is not just screening. So what lessons are we meant to draw from the example?

Looking at the study. It began 15 years ago for men aged between 50-69. So those that are still alive will be now be aged between 65 and 84 – many of those that died will have died for reasons unrelated to prostate cancer and some of these will have benefited from a longer life because a prostate cancer that would have killed them earlier was picked up by the test. So all cause mortality seems a poor measure of success. Surely a better one would something like average life span?

One criticism of using the PSA test is it missed the early detection of some aggressive cancers. Is that a reason for not using it? It depends on what happens instead. Is the idea to use a different test? Surely not testing at all is going to miss even more aggressive cancers?

great fun for statisticians

Does prostate cancer take 15 years to develop ?

Have lab tests got better over 15 years ?

PSA test results are all so called consultants look at after after treatment such as Xray blasting of the the prostate.

PSA test is cheap enough.

And what else you got ?