Suicide is a bit of a hit and miss affair. I can think of six cases of people I’ve known who’ve taken their own lives. One, a very successful business executive, threw himself out an office window; he survived the fall, only to hang himself a couple of years later. The girlfriend of a lodger survived throwing herself in front of an underground train: she left it too late and got blown back onto the platform, breaking a hip. She too, some while later completed the job by jumping off Beachy Head. A business acquaintance, having been diagnosed with Parkinson’s blew his brains out with a shot gun, literally, leaving his wife to clear up the mess. The girlfriend of another acquaintance killed herself when her boyfriend went off to university, only for the boyfriend, my acquaintance, to follow suit on the anniversary of her death. Finally, a university fresher I knew, depressed and alone in his halls of residence, killed himself during the first lockdown. Apparently a grim and drawn-out death. I blame Ferguson, Whitty, Boris and the other nutters for that one.

Of the six, two failed the first time. Two had access to shotguns and made a good job of it. Two others used a drug cocktail, which while fatal, was neither quick nor, so I’m told, painless. While jumping off Beachy Head shows a level of determination beyond my imagining. Half were in their late teens or early 20s. Each one a tragedy in its own way, leaving behind misery, heartache and untold complications.

To my mind only one of these deaths made any sense. I suspect a psychiatrist would concur. However, as we’re seeing in Canada, and who knows perhaps all too soon in the U.K., it won’t be doctors making the decision, it will be ‘human rights lawyers’ should proponents succeed in following Canada’s lead and making state assisted suicide a human right, opening the floodgates to those who, with help, could get their lives back on track.

Given that two of the suicide attempts I detailed resulted in failure but significant injury, I can see that there is an argument for getting the state and a doctor involved – the argument based on ‘utility’. Surely, if a doctor were to be involved, while the suicide may still be, in the eyes of the rest of us, a mistake, then, to quote Macbeth:

If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well it were done quickly.

Surely, the involvement of a doctor would at least make it all cleaner, more efficient.

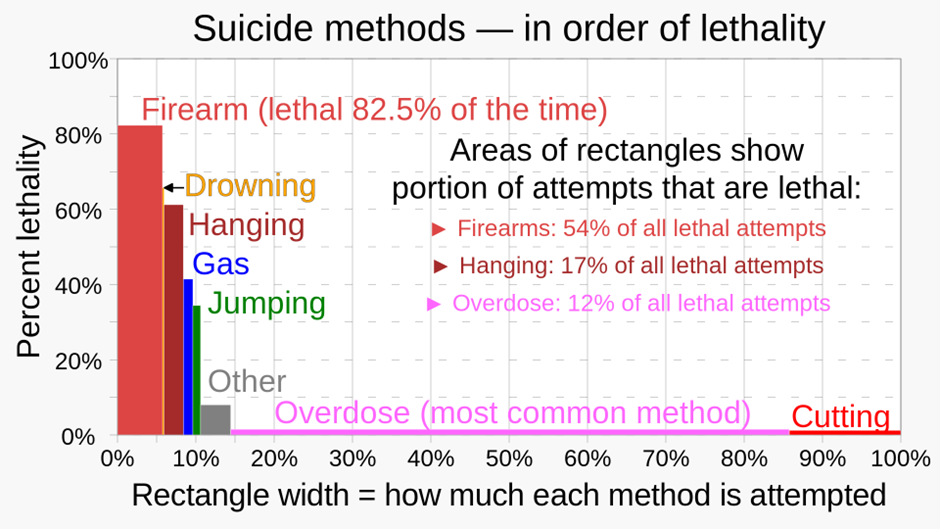

However, it isn’t only my acquaintances who have a tendency to botch their suicide attempts; most efforts are unsuccessful. I doubt any data on the efficacy of suicide attempts are particularly accurate, but the chart in Figure 1 reflects the estimates I’ve seen. 17.5% of attempts using a firearm fail. 40% of hangings fail. Heavens, even 70% of jumpers survive! One can only imagine the injuries this all results in.

Apparently, only about 5% of people who survive a suicide attempt go on to kill themselves within the next five years. Clearly, most people who attempt suicide and fail get over it. I’m not sure that getting professional help to improve their first-time success rate is necessarily a good idea.

However, are doctors likely to improve on your own ham-fisted efforts at ending it all? Having looked at the evidence, I was surprised to find it appears you’d be better off consulting a slaughterman than a doctor. Slaughtermen kill hundreds of large mammals every year with barely a misstep.

It might not immediately occur to you, but doctors, certainly in countries where they already have assisted dying or the death penalty, do a fair bit of killing already, though I’m not sure they can hold a candle to slaughtermen.

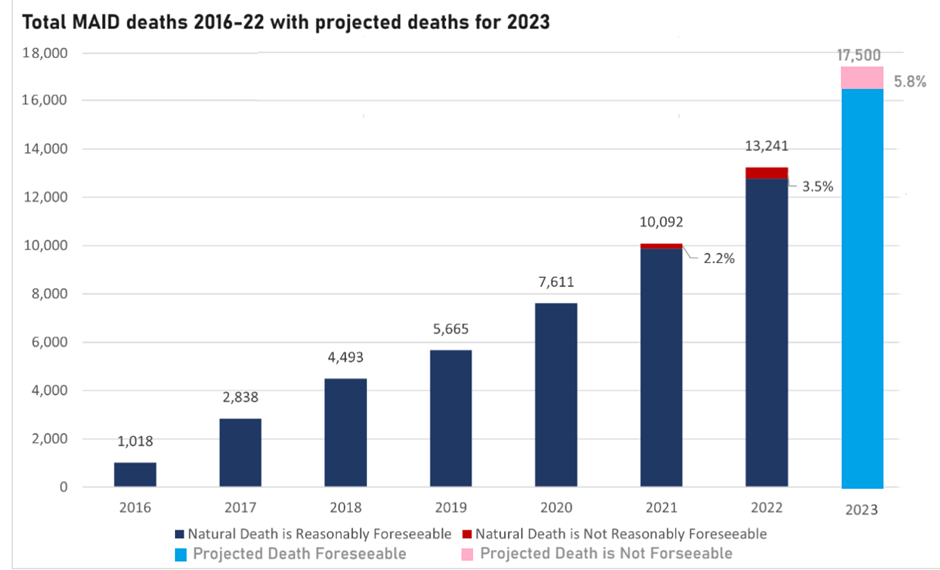

There were 24 executions in the USA in 2023. Back in 1999, enthusiasm peaked when 98 prisoners were put to death. By way of contrast, in nearby Canada something like 17,500 people will have been ‘euthanised’ in 2023. That’s almost 50 deaths per day! Quite something. Canada, with a population one eighth the size of the USA, is killing twice as many people each day as the U.S. executes in a year.

You might think that with this level of killing both Canadian and U.S. doctors would have it down to a fine art. Apparently not!

Executions of death row inmates takes various forms: lethal injection, gas, the electric chair, hanging and firing squad. All are fraught with problems. There are newspaper articles galore detailing no end of horrors: how long it takes for the prisoner to die, difficulties getting the needle in the vein, failures of electric chairs, firing squads missing. Having killed a few chickens and, grimly, once a very sick old ewe on an Australian sheep farm, I have every sympathy for those called to do the killing and the real-life difficulties that present themselves as you make a hash of what, on paper, would seem to be the most straightforward of tasks.

John Wyatt, Emeritus Professor of Neonatal Paediatrics, has written a very moving piece in the Spectator concerning the likely impact on practicing doctors if a bill recently drafted by the Scottish Liberal Democrats legalising ‘assisted dying’ gets passed by the Holyrood Parliament. Doctors would then find themselves being expected to kill patients. How to square this with a doctor’s primary objective ‘do no harm’? In the article he notes that the Hippocratic code prohibits physicians from participating in judicial executions. Clearly, the ethics around extending a doctor’s duty to killing their patients presents huge ethical dilemmas.

To me, one of the most intriguing points raised by Wyatt is that “once the physician has certified the death, he will be legally instructed to produce a false and patently misleading death certificate – saying that the certified cause of death was the underlying disease, rather than the lethal poison that had just been administered”. Given the controversary during the ‘pandemic’ in the recording of deaths ‘with’ or ‘of’ Covid, and the corruption of ‘all-cause’ mortality data, a sceptic, such as me, is highly suspicious of this particular sleight of hand.

It will be argued by many that there’s a vast difference between executing a murderer and ending the life of someone, either terminally ill or who, for whatever reason, wants some help ending his or her life. Many will argue that there’s a difference morally. But one question I’d never previously considered was the ‘how’. How do you go about killing people?

In addressing this problem, I’m indebted to one of the Daily Sceptic‘s regular below-the-line commentators who, beneath one of my recent articles, linked to a blog post by Sir Desmond Swayne MP which included a report by the Oregon Health Department, entitled ‘Death with Dignity’. The report details the annual results of Oregon’s Assisted Dying Act.

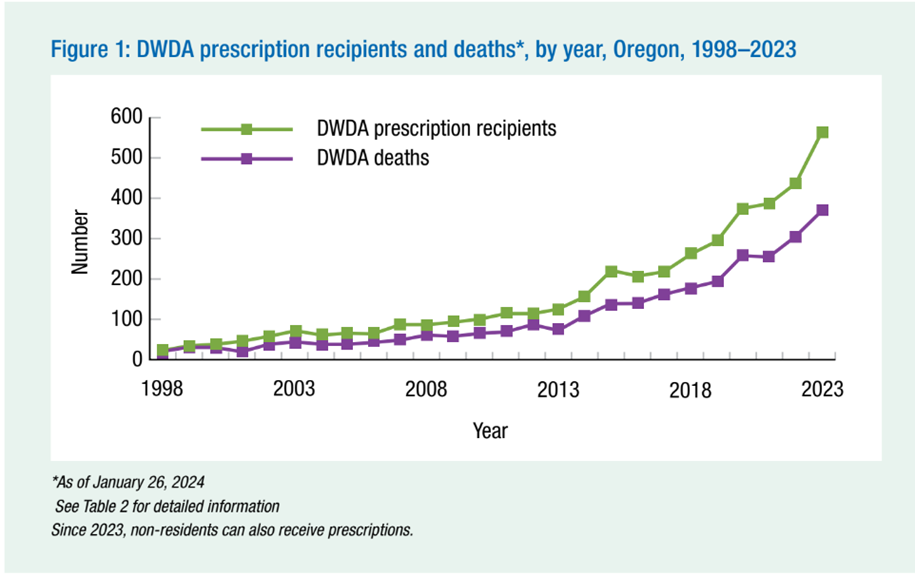

It’s in the area of ‘efficacy’ that the Oregon report is so illuminating. Let’s start with a bit of context. In Oregon they aren’t killing people on the industrial scale of Canada but they still manage to kill more than 20 times the number executed across the entirety of the USA.

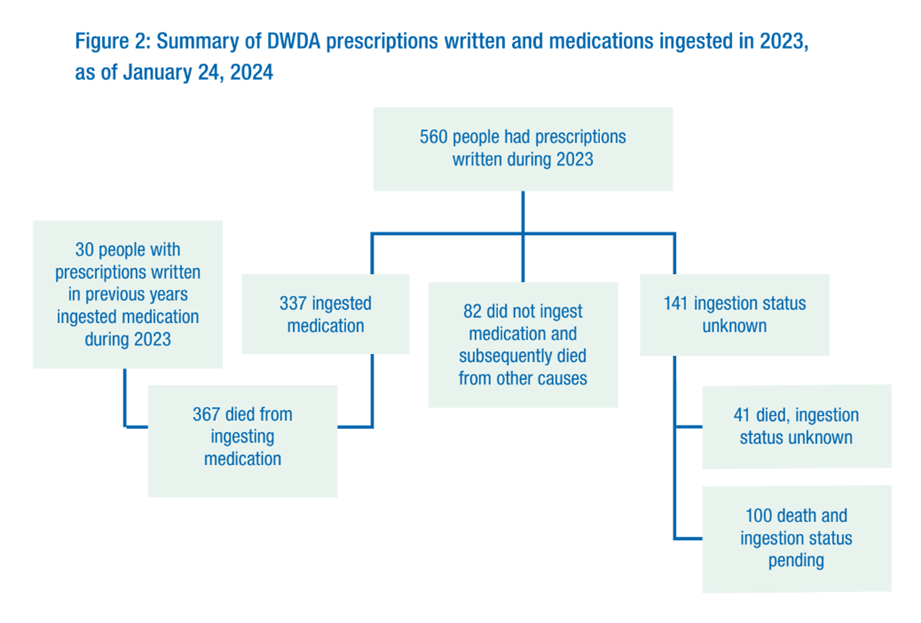

Five hundred and sixty people were prescribed the lethal drugs in 2023. Of those, 367 – just 65% – died from the cocktail. The other 193 people didn’t survive the drugs – they either didn’t take them, died of something else before ingesting the drugs or the medics lost track of them.

The report includes a handy summary of what happened to the those prescribed with the drugs in 2023, which I’ve reproduced in Figure 5.

As an aside, it’s worth noting that 17 patients, presumably from the group who didn’t ‘ingest’ the drugs, outlived the six months residual span of life, the maximum time that, according to the doctor, a patient can be expected to live and still qualify for assisted suicide. Be that as it may, you can see that nothing is straightforward, nor – if you are someone considering suicide – is it terribly reassuring.

The following tables are lifted from the report.

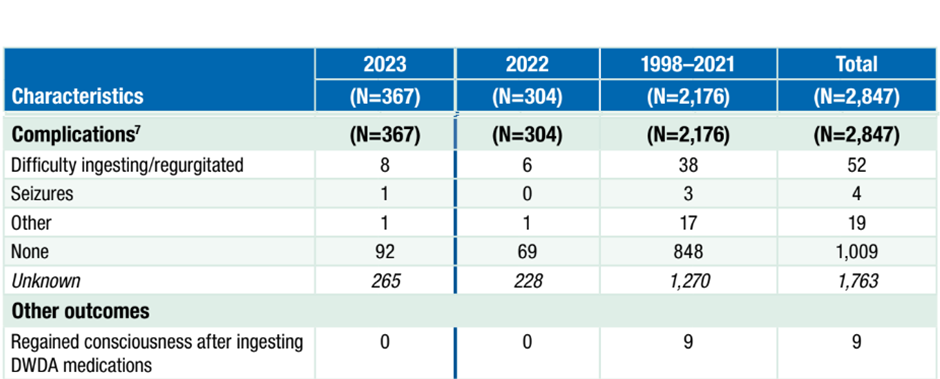

Firstly, let’s look at ‘complications’. Well, the first thing that strikes you about the findings is how incomplete they are. Of the 367 who took the poison there are no data for 265 (72%) of them. Of the 102 (28%) for whom we have data, 8% had difficulty swallowing or regurgitated the poison. One patient had a seizure.

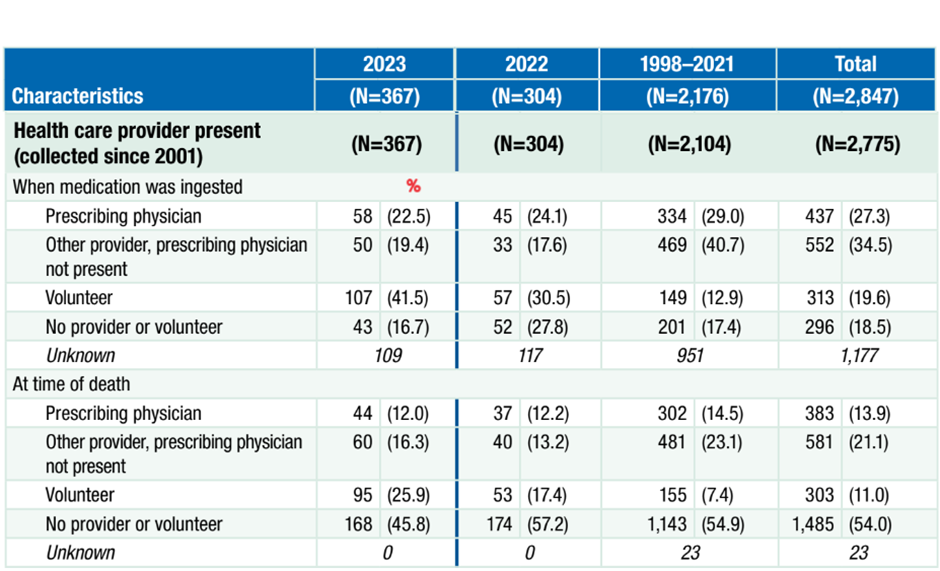

It seems odd that for most patients no data are available. However, the next table gives you some clues as to why this might be. Figure 7 shows who was with the patient when he or she either took the drugs or died from the drugs. For only 58 (16%) of the 367 patients was the prescribing doctors present when the ‘medicine’ was ingested. And in only 44 (12%) of cases was the doctor present when the patient died.

In 14 cases the doctor appears to have left the patient between ‘ingestion’ and death. Similarly, while of the 258 cases for which there are data, 43 were seemingly alone when they ingested the ‘medicine’, by the time of death 168 were seemingly alone. This all suggests the ‘medicine’ isn’t all that fast acting.

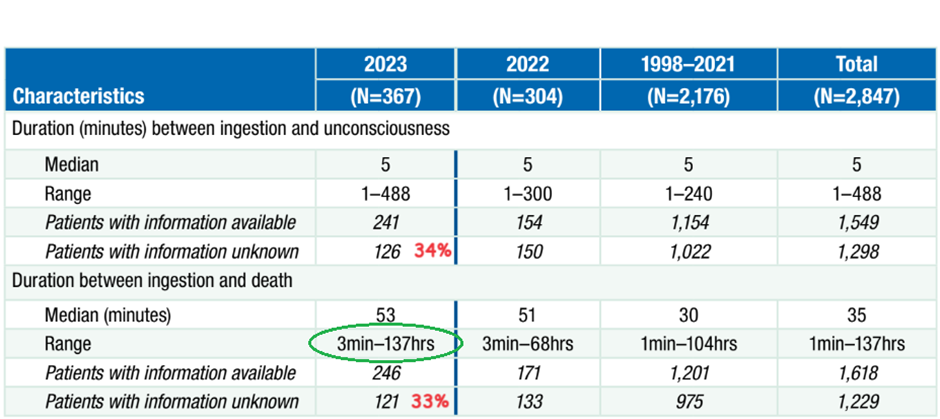

Figure 8 tells us just how fast the ‘medicine’ takes to do its job. For 34% of the patients we have no data. Of the 64% for whom there are data it took from one minute to over eight hours (488 mins) for the patient to lose consciousness, with a median time of five minutes. Death took rather longer. The median time to death was 53 minutes, while at least one poor soul took 137 hours, not far off six days to die! Can you imagine if this happened in an execution chamber, or an abattoir come to that.

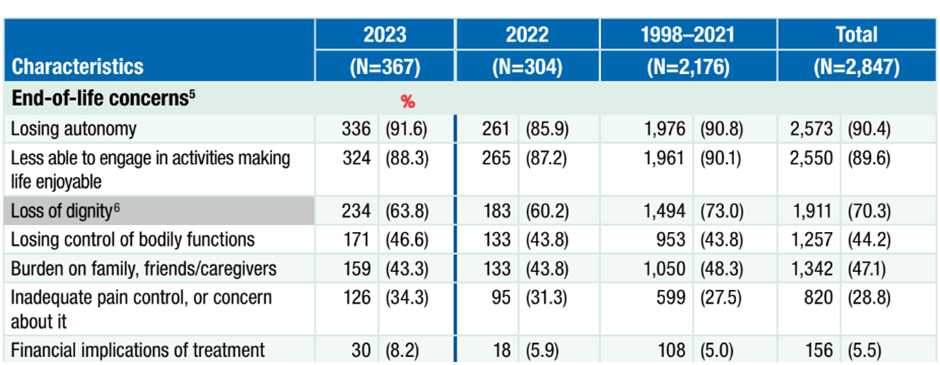

Figure 9 has data on the ‘why’. Why did these 367 people want to die? Only 34% mentioned inadequate pain control. For most it was losing autonomy, being a burden on their family, or just not being able to enjoy life.

The message I take from the Oregon report is that the mechanics of all this look very messy. Admittedly, these data are limited to Oregon. Maybe they do things better in Canada or the Netherlands or Belgium. Maybe they’ll do it better in Scotland or eventually England and Wales when it’s inevitably introduced – but I doubt it.

I suspect killing a person can be every bit as messy and distressing as I found killing that old ewe in Australia 40 years ago. Certainly, having been fairly equivocal about assisted dying, having read this report I can’t think it’s something I’d be happy recommending for my loved ones.

I’ve always been a bit of a doodler. One thing I frequently drew while in boring meetings was a guillotine I could build in my garage. I’d decided that it would probably be the quickest, most pain-free way to go. The design was ingenious if I say so myself. However, in recent years I’d rather assumed I’d be happy to let the professionals take over when the time came. Well, not any more. I must go and dig out those old notebooks, I suspect my home-made guillotine or the local slaughterman will prove the better bet.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.