Last month, everybody’s favourite intergovernmental agency, the World Health Organisation (WHO), published a “new toolkit empowering health professionals to tackle climate change”. The toolkit is the latest attempt to enlist one of the most trusted professions into the climate war. But not only is this transparently ideological and condescending ‘toolkit’ lacking in fact, it requires ‘healthcare professionals’ to use their authority to eschew science and lie to their patients and politicians. The climate war is, after all, political.

The problem for climate warriors of all kinds since the climate scare story emerged in the 1980s and became orthodoxy in the 1990s and 2000s has been the rapid improvement of all human welfare metrics the world over. On the one hand, all life on Earth and the collapse of civilisation hangs in the balance – that is supposedly the implication of data that shows the atmosphere has got warmer. But on the other hand, people living in economies at all levels of development are today living longer, healthier, wealthier and safer lives than any preceding generation. The era of ‘global boiling’, as UN Secretary General António Guterres put it, also happens to be the era in which unprecedented social development has occurred.

That is a paradox if you accept the green premise that economic development comes at the expense of the climate. The UN, which has staked its authority on being able to address ‘global’ issues such as environmental degradation, is committed to defending the ‘global boiling’ narrative. But, at the same time, actively trying to retard the development of low-income countries risks undermining its authority in the developing world.

The statement made by the WHO’s introduction to its new toolkit epitomises the feeble efforts to square this circle, which try to spin interference in the development of low-income countries as being for their benefit:

Our world is witnessing a concerning trend of warming temperatures, extreme weather events, water and food security challenges and deteriorating air quality. The frequency and intensity of these events are surpassing the capacity of both natural and human systems to respond effectively, resulting in far-reaching consequences for health.

Surprisingly, for a ‘toolkit’ aimed at people such as doctors, who have a proven capacity to understand scientific literature, the toolkit offers little evidence in support of these claims. It says that “changing weather patterns and extreme weather events can reduce crop yields, potentially leading to food insecurity and malnutrition” and that the “breeding window for mosquito-borne disease is broadening due to changing weather patterns”. The reference for both of these claims is given in a footnote, which provides a link to the 2023 IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report, which says in relation to the first claim:

The occurrence of climate-related food-borne and water-borne diseases has increased (very high confidence). The incidence of vector-borne diseases has increased from range expansion and/or increased reproduction of disease vectors (high confidence).

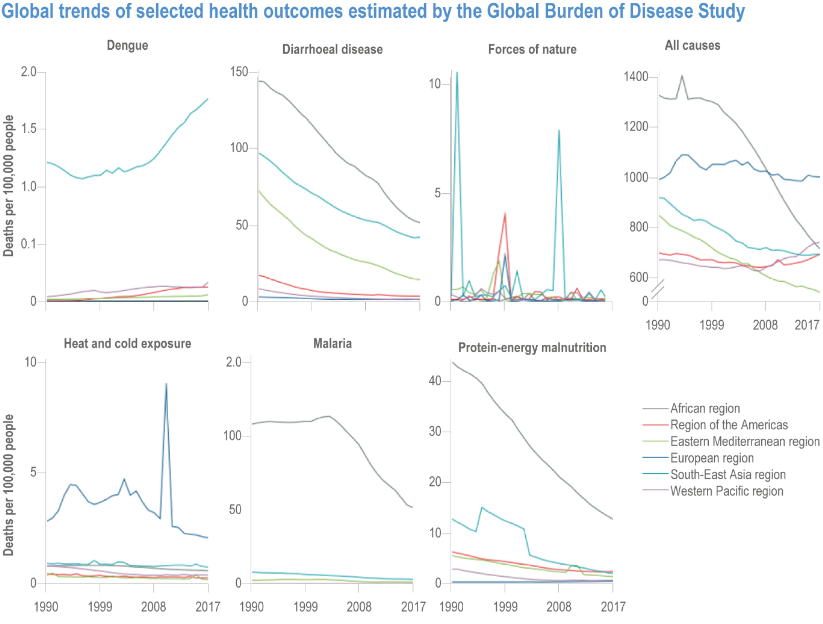

But dig a little deeper into the IPCC’s discussion on vector-borne diseases and you find the following figure depicting mortality risk of various climate-related factors for six regions of the world.

As the data clearly show, since 1990 there have been radical reductions in mortality caused by malaria, malnutrition, diarrhoeal disease, natural disasters and exposure to temperature extremes. The only departure from those trends is dengue, which in any case is of far less significance than the other factors, claiming approximately just 1.75 lives per 100,000 per year, compared with malaria, which claims more than 50.

How do these data compare with the WHO’s claim that “the frequency and intensity of these events are surpassing the capacity of both natural and human systems to respond effectively, resulting in far-reaching consequences for health”, and the “occurrence of climate-related food-borne and water-borne diseases” and the “incidence of vector-borne diseases” have increased? They do not compare. In Africa, deaths from malnutrition have fallen by three quarters between 1990 and 2017. Diarrhoeal disease mortality has fallen by two thirds in the same period. Malaria deaths have halved. Consequently, more than 10,000 fewer infants die in the world each day than died each day in 1990.

This is, or ought to be, all the more remarkable to anyone who tracks developmental data, because of the WHO’s longstanding attempt to link these diseases of poverty to climate change. In the 2002 World Health Report, the WHO claimed that 154,000 deaths were attributable to climate change, almost exclusively in High Mortality Developing Countries (HMDCs) – a figure obtained by estimating climate change’s impact on each of these diseases of poverty. Yet despite the radical progress that has been shown since 2000, the WHO has shown no interest either in revising its understanding of climate change or in developing an understanding of what has driven these improvements in global health, in spite of its name. Instead, it has doubled down on the climate-health narrative.

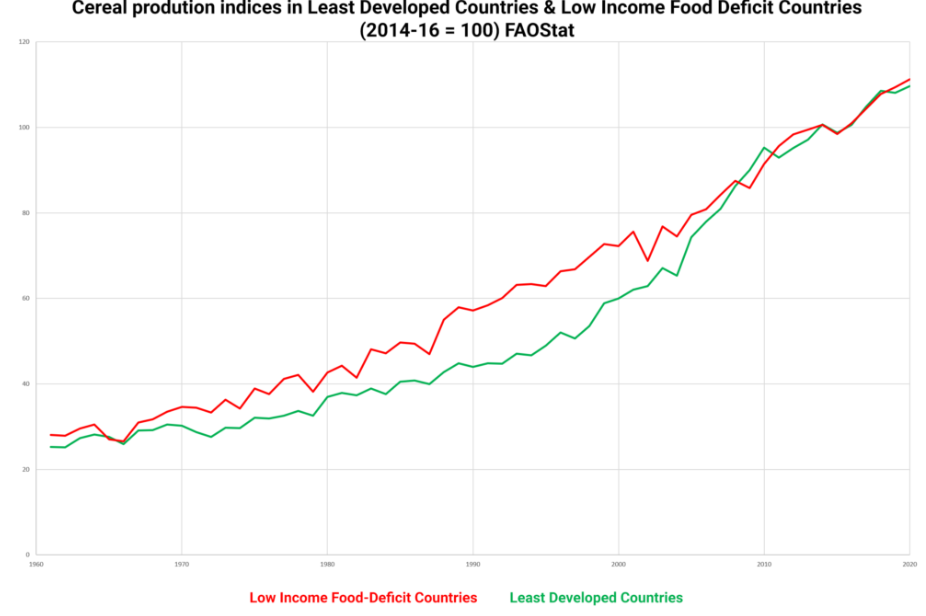

A similar ‘paradox’ can be shown by comparing the WHO’s statements on food security with other UN agencies’ data. There is no evidence of climate change adversely affecting agricultural production in vulnerable economies.

Yet the WHO’s toolkit urges “health professionals” to “communicate” the urgent climate crisis to ordinary people and to use their authority to influence politics:

Things you could say to a policymaker: Climate change is here now, and I am already seeing the impacts on my patients’ health. The health of some people is affected more severely, including children and elderly people, disadvantaged communities, remote communities, and people with disabilities or chronic illness.

People are living longer and healthier lives. Infant mortality is way down. Far fewer people are living in poverty. But the WHO wants doctors and nurses to claim that the opposite is true. And worse than that, the toolkit advises those doctors and nurses not to debate:

Don’t debate the science Don’t get caught up in conversations that question climate science. It’s not up for debate. If conversation veers into this territory, redirect it back to your professional expertise and the links between climate change and health.

But there are no “links between climate change and health”. And if there appear to be, these local or regional health trends run counter to the global trends. Therefore, there must be a better explanation than ‘climate change’. It may well be that extreme weather afflicts a place, or even that unusual weather causes the population of that place a number of problems, as it always has. But ‘extreme weather’ is both rare and as yet not attributable to climate change, on the IPCC’s own analysis. And so, if small changes in weather are coincident with negative economic change or health metrics, the cause is less likely to be meteorological than political in nature. For example, incompetence, especially that of undemocratic regimes’ bureaucracies, is very often the cause of hunger, thirst and the lack of basic services. And in their haste to find politically expedient correlations between weather and welfare metrics, researchers fail to consider alternative causes, despite the knowledge that humans are far more sensitive to economic forces than to nature’s whims.

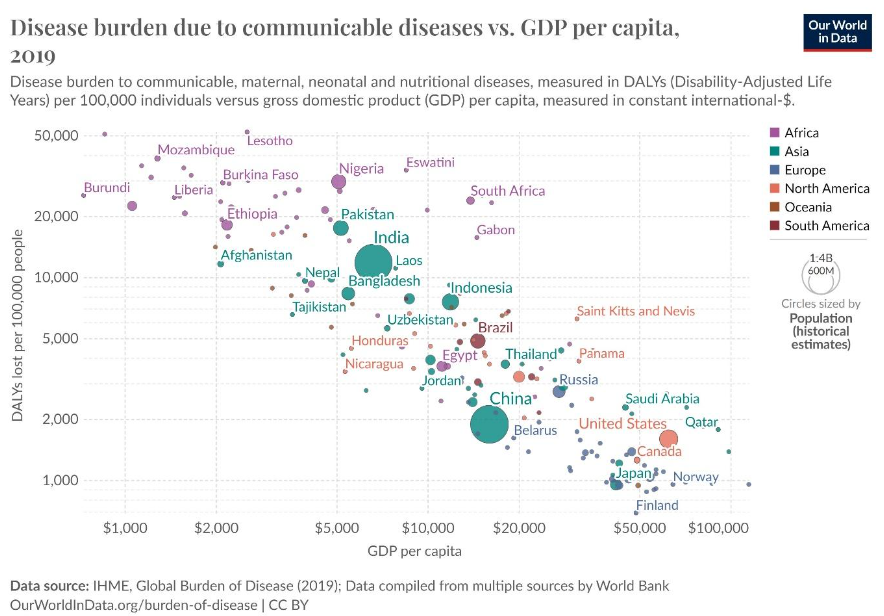

Don’t believe me? Well, the evidence is extremely stark. Whereas the WHO wants to persuade doctors to ignore science to claim there are “links between climate change and health”, by far the strongest predictor of health is in fact wealth. Accordingly, the WHO 2002 report found practically no climate-related deaths in ‘Low Mortality Developing Countries’ and ‘Developing Countries’. There are no deaths “from climate change” where malaria, malnutrition and diarrhoea are eliminated by rising income levels.

Seen from this perspective, the WHO’s mobilisation of health professionals looks very much like a political campaign against wealth. Only such an ideological – and anti-science – aversion to wealth could put such emphasis on the link between health and weather, because whereas doctors can and should say that income and health are linked, the WHO presses them not to: the best thing that can be given to poorer people is ‘stable weather’, apparently, not higher incomes. The toolkit even anticipates this criticism, advising people how to answer the argument that “climate action is perceived as detrimental to the economy”. According to the WHO, this is “an untrue and unhelpful perception held by some people… which was repeated by some businesses and governments to delay the implementation of climate solutions”. A conspiracy theory, no less, which is supported only by the highly dubious claim that “for every dollar spent on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, approximately $2 are saved in health costs”.

Any doctor who took such an extraordinary and unevidenced claim about a new drug at face value and promptly started prescribing it to their patients would have his or her licence taken away. Britain, for instance, spends around £10 billion per year on subsidising its green electricity transition alone, yet there is no evidence of the NHS budget benefiting by £20bn. An analysis of Germany’s Energiewende estimates the annual cost at €45 billion, yet per capita expenditure on healthcare rose from €3,500 in 2009 to €5,700 in 2021 – an increase of 62%. Moreover, Germany’s green deindustrialisation has come at a heavy price, signalling to the world that not even a first-tier industrialised and wealthy nation can survive such environmentalism, with far reaching consequences looming for similar policies in the rest of Europe. The country’s status as Europe’s deep-green policy champion has passed and now half of Germans believe that lower prices should be put before emissions-reduction policies. German tractors, and for that matter French and Dutch ones as well, aren’t heading to the capital’s streets to protest against green economic and health miracles. The WHO’s claim is simply mad.

The reason the WHO’s toolkit is so bereft of evidence and logic is because it’s just political propaganda. The document credits authors who are not medical doctors and climate scientists, but psychologists at the Centre for Climate Change Communication located at George Mason University, led by Dr. Ed Maibach. As I have pointed out previously in the Daily Sceptic, climate shrinks’ unwelcome intrusion into climate politics does nothing to improve debate and only serves to antagonise increasingly intense conflicts. And their involvement in producing the WHO’s toolkit is no exception. This remote, conflicted intergovernmental agency claims the authority of ‘experts’, but its guidance instructs doctors to eschew science, evidence and debate – it literally advises them not to engage in debate – and instead to promulgate green ideology: the mythical claim that there are ‘links’ between climate and health, that the green ‘transition’ will improve health and that complying with emissions targets is cheap as chips.

The toolkit may give ‘healthcare professionals’ the justification to lie to the public and politicians, but that’s not ‘empowerment’, it’s just fibs. And its recruitment of psychologists to mobilise doctors and nurses as the instruments of a political agenda is yet more evidence of the urgent need to dismantle the WHO, for the sake of billions of people’s health and wealth.

Subscribe to Ben Pile’s The Net Zero Scandal Substack here.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.