Public health has come into its own over the past few years: a once-backwater profession now promoted to be the arbiters of liberty and human relationships. Outbreaks of diseases associated with death at an average age of about 80, or even purely hypothetical, are now sufficient reason to close workplaces, close schools, upend economies and convince people to turn on their noncompliant neighbours. The result, while impoverishing many, has driven an unprecedented concentration of wealth.

For the average public health professional, this new world order offers better opportunities. Once confined to writing training materials for clinic staff in remote forgotten villages or chasing up diarrhea cases from a local French deli, pandemics bring excitement, make headlines and generate good financial return for the sponsors as well as those serving them.

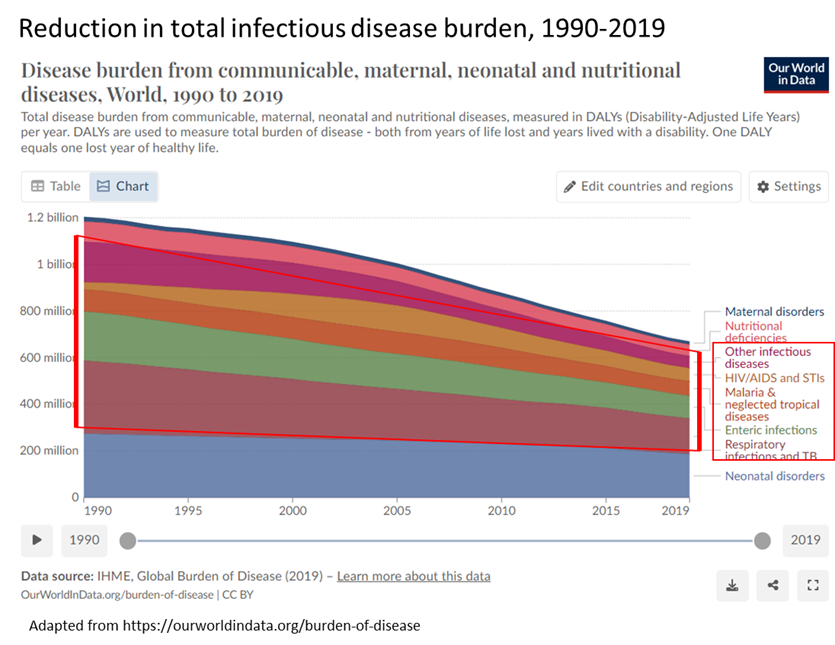

Generating the fear and compliance necessary to build this new and somewhat parasitic model of public health has been no mean feat. For decades, life expectancies have been rising globally while infectious disease deaths have plummeted. With modern medicine, antibiotics and the broad immunity ensured by a century of global travel and intermingling of peoples, the old cadence of regular pestilential outbreaks was broken, with nothing of real note globally since the Spanish Flu back in 1919. This is not an easy canvas to work with if the public must be convinced that things are getting worse.

COVID-19, on objective assessment, should also have provided little help, having appeared just down the road from the only high-security lab in China where the same type of bat virus was being genetically manipulated. It was an unlikely candidate to support a narrative of ever-increasing pandemic risk from a nature abused by humanity. But a subservient media dutifully got behind such a story, proving that Occam’s Razor can be dulled. While Covid alone could not support a long-term industry, it has served as a wonderful platform on which to build.

A few seeds can create a harvest

The COVID-19 response did not appear from nowhere. A public health stream concentrated on catastrophic responses to rare public health problems had been growing parallel to orthodox evidence-based approaches for a decade. From 2018 the World Health Organisation (WHO), with growing private funding, was working alongside CEPI, the new international partnership to use public money to develop private sector vaccines. Prioritising vaccine-based responses to outbreaks, WHO developed the concept of hypothetical diseases that could then justify investments of a magnitude that real world outbreaks could not. COVID-19 served as a template to see how such responses could be globalised, irrespective of individual risk.

If risk could be disconnected from reality, then the concept of diseases being existential threats to humanity could gain greater traction. This would then justify future investment that the self-appointed saviours of humanity may require. The exponential-increase concept, mainstreamed during Covid but actually illogical for disease outbreaks in which acquired immunity mitigates further threat, could supply the urgency needed to drive funding, and bypass laborious regulatory requirements. Any delay could be argued to be making matters exponentially worse. No national leader could survive the headlines such claims would generate. The pandemic industry, based on mirages but always retaining a kernel of demonstrable threat, had an almost unassailable business model.

The kernel of demonstrable threat is the reality that diseases happen, viruses exist, and they sometimes transfer from animals to humans. HIV did, so did the Black Death (Plague) and the Spanish Flu. The reality that Plague and Spanish Flu killed mainly due to a lack of antibiotics, and that HIV took decades to even come to attention in a remote area before modern diagnostics and communications, are irrelevant if the media chooses them to be so.

WHO and the cartoon industry

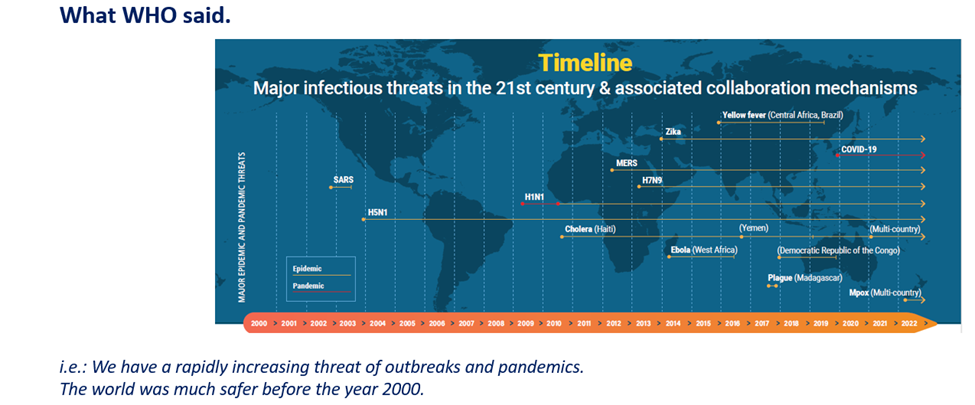

The old adage “a picture is worth a thousand words” is particularly relevant in an age when reading more than 280 characters is considered burdensome. WHO, like other institutions trying to sell a message, understands this. The use of graphics can also simplify a message, reducing the probability that the concept being imparted is undermined by serious reflection. The recent WHO report ‘Future Surveillance for epidemic and pandemic diseases: A 2023 Perspective’ starts and ends with cartoons which read worryingly like propaganda (although the last, on page 105, seems perhaps too dystopian to sell a product). WHO uses a graphic that superbly epitomises the messaging behind the pandemic industry, its lack of rigour and integrity.

We could also dwell on a different one (below) from the WHO’s ‘Managing Pandemics: Key facts about major deadly diseases’. But that would be silly.

Although the intent of WHO with this childish graphic is clear, even this is contrary to its own evidence.

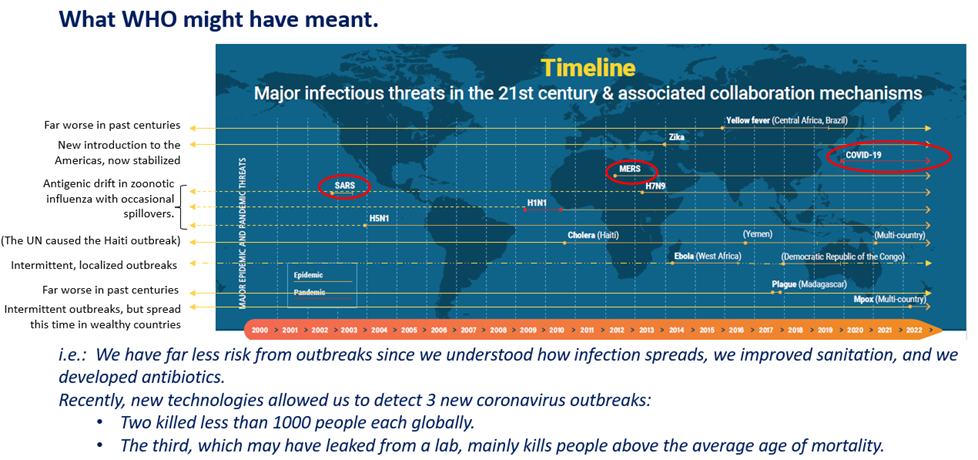

The graphic of interest is used in both the Future Surveillance and Managing Pandemics reports. Two versions are provided below; the original WHO version and a modified one that perhaps WHO would have used if trying to impart information in context.

WHO, in noting the outbreaks in the first version above, ignores the fact that the pathogens involved, with a few exceptions, are not new problems. They have caused outbreaks for centuries and now cause much less harm than previously before. Of the three exceptions that appear newly arisen, two killed less people in total, globally, ever, than eight hours of one of WHO’s former priorities, tuberculosis. The other is COVID-19, which appears likely to have resulted from a somewhat inevitable mistake of the same pandemic-industrial complex that is now seeking funding to prevent the next one. The ‘mistake’ part is why the Obama administration paused funding for Gain of Function research on the understanding that accidental releases will probably happen.

Of the pre-existing problems in the figure, influenza caused the Spanish Flu in the pre-antibiotic era, killing 25 to 50 million or more in a far smaller global population, while ‘plague’ is thought to have killed a third of Europe during the Black Death. Cholera once devastated whole regions, and Yellow Fever caused devastating outbreaks that dwarf its burden today. The rest are viruses that have probably been infecting humanity for thousands of years but never in sufficient numbers to make a significant mark (Zika was in the news in 2016 because it finally reached the Americas, not because it was new).

The lower graphic, if extended backward, would somehow need to show a rapidly decreasing disease burden as sanitation, nutrition and healthcare has improved, and risk therefore reduced. A very different picture than the artists seemed to be trying to put across.

Unfortunately, the misrepresentation of pandemic risk is not an aberration. Over the past four years the health industry has also misled the public regarding the requirement of vaccination to achieve immunity, the advisability of throwing poor people out of work in crowded cities to stop a respiratory virus, and the necessity of preventing young girls from going to school in order to protect their grandmas when this would inevitably increase child marriage and subsequent years of nightly rape and abuse. When an industry finds that misinformation pays, and the media abrogate their role of questioning obvious conflicts of interest, the pressure for honesty and integrity declines.

So, the reader is left to decide whether the misleading impression given by WHO is accidental or reflecting intent. WHO is significantly funded by private corporations and investors who benefit from mass vaccination responses of the type proposed for future pandemics. These corporations owe it to their investors to promote such responses, just as agencies such as WHO have a responsibility to combat corporate predation in healthcare. The above misrepresentations of pandemic risk are not isolated but reflect a theme among international health agencies. Perhaps public-private partnerships, inevitably subject to human greed, must always end up exploiting rather than serving the public.

Fairy tales, fraud and public health

Does any of this really matter? Telling stories, or ‘telling tales’, is a pastime going back tens of thousands of years. Our culture is steeped in fairy tales, and they are good for teaching children some of the fundamentals needed to get by in society – how some people can be trusted, some not, and how some even set out to harm others. It is hard, however, to see that creating fairy tales is within WHO’s mandate. Fairy tales, clearly labelled as such, may have a limited role in public health as a tool to encourage healthy lifestyles, but never to promote fear.

Inventing stories to mislead others in order to extract wealth is also an age-old activity. It can be fairly innocuous or even positive when entertainment is involved. However, deliberately misleading people for profit, under a false pretense of helping them, is usually characterised as fraud. This would clearly be off limits for an international organisation or, ethically, anyone working in public health.

Inventing a narrative to deliberately lead people, countries and organisations down a path that will harm them would be taking this subterfuge to a whole new level. Behavioural psychology was mis-used to spread fear during the Covid response under the mistaken belief that this was for some ultimate good – that scaring people would somehow protect them. But using it to actively harm most people to benefit a few, when your mandate is to help the many, would be fundamentally worse.

Diverting funds from high-burden diseases to pharma profit is actively harmful. Children die from lack of medication when supply lines are interrupted or because their parents are simply impoverished when workplaces are closed. Abuse of girls increases when schools are closed. Malnutrition will increase when markets are closed and tourism ceased. Health services will decline when resources are diverted to a new mass vaccination program for a disease against which the recipients already have immunity. Falsifying risk and imposing a response profitable to sponsors is beyond fraud when applied to public health. It is something far more malicious.

WHO’s constitution holds that health consists of physical, mental and social well-being. It holds, together with basic public health ethics, that communities be provided with accurate information, in context. These communities can then make informed decisions in keeping with their own culture, beliefs and priorities. There is no way around this without abrogating basic public health ethics and the fundamentals of human rights.

Applying these principles to the management of outbreaks and pandemics, together with the far less profitable areas of global health, would be a good basis for pandemic preparedness. This would require honesty regarding pandemic risk and regarding the far more serious health issues that harm and kill most people. It would require health to be seen in terms of the broad areas of well-being that WHO once prioritised. Those of us working in the field know this. It is on us to decide how we apply this knowledge, and how we prioritise the welfare of others.

Dr. David Bell is a clinical and public health physician with a PhD in population health and background in internal medicine, modelling and epidemiology of infectious disease. Previously, he was Director of the Global Health Technologies at Intellectual Ventures Global Good Fund in the USA, Programme Head for Malaria and Acute Febrile Disease at FIND in Geneva, and coordinating malaria diagnostics strategy with the World Health Organisation. He is a Senior Scholar at the Brownstone Institute, where this article first appeared.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.