The first museum in the world to display Benin Bronzes from the February 1897 Expedition was London’s Horniman Museum, and in November 2022 the Horniman became the first to give away its collection.

The Illustrated London News (ILN) of April 10th 1897 showed a small array of items “believed to be the only curiosities which survived the flames” after Benin’s Oba fled and his palace was accidentally burned, and “which have now been acquired by Mr. Horniman for his Free Museum at Forest Hill”. The seller “Mr. W.J. Hider RN” had asked £100 for his souvenirs of the British expedition and has always been thought to be one of its officers: but we can reveal that he was an enterprising Royal Marine Light Infantry medic from the Naval Brigade which overthrew the Oba’s murderous regime, and his sales pitch was less than candid.

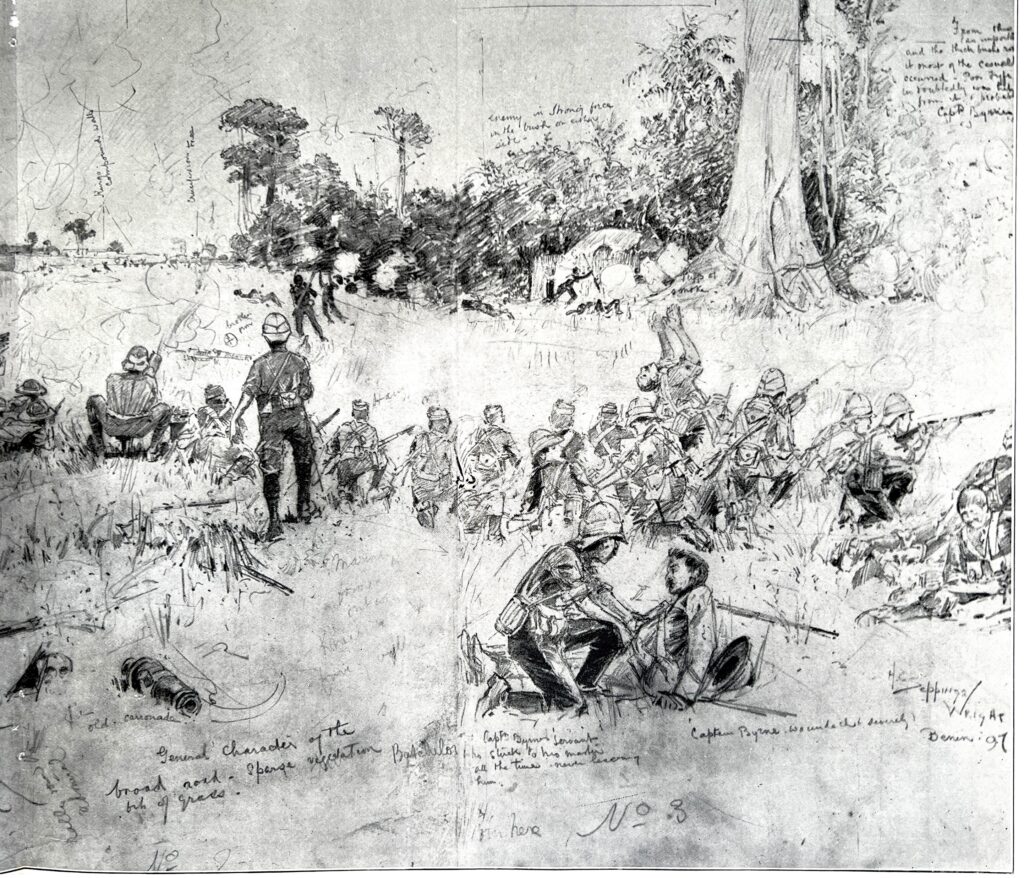

Second Sick Bay Steward 150304 Hider, William J. (1873-1962) of the cruiser HMS St. George, flagship of the Royal Navy’s Cape and West Africa Squadron, may have been working alongside the ship’s surgeon Dr. C.J. Fyfe as he was shot dead while tending Marine Capt. G. Byrne – shot in the spine – just as the expedition neared Benin (pictured below). Byrne was to die of his wound in London the following month. Hider fibbed about his birth date to enlist in 1889, well underage, and his son (born on Ascension Island) followed him into the Navy and became a Chief ERA who won the BEM for saving his torpedoed ship in 1943.

The ILN reported that Hider’s haul at the Horniman included a Snider rifle, ivory bracelets, a wooden mirror frame, fans, two ivory executioner’s maces and “a couple of bronze handbells, rung to announce a human sacrifice”. He must have known very well – though apparently failed to tell the museum’s owner – that thousands of remarkable bronze and ivory pieces had indeed survived the palace fire and were on their way to London in crates or in the trunks of officers, rather than a rating’s kitbag. But 2SBS Hider got to Mr. Horniman first.

The British Museum, initially sceptical, later accepted ‘bronze’ plaques and heads (actually brass) and mounted an exhibition in October 1897 – though still unconvinced that these masterpieces of lost-wax casting were indigenous African work – and has added to its world-leading collection in the years since. German museums and collectors competed to buy from London auctions and dealers these African artworks whose significance the British were strangely slow to appreciate, and Mr. Horniman bought more too.

In 2022, a century and a quarter later, the Horniman gave all 72 items of its Benin collection to Nigeria. Trustees were encouraged by their Chief Executive Dr. Nick Merriman (who’d arrived in 2018 and the next year declared the museum’s climate emergency) and press coverage of the handover predicted a wave of restitutions, not least from the British Museum. Professor Aba Tijani, head of Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments, jubilantly displayed the six pieces he was removing at once. They included one of Marine Hider’s executioners’ maces – whose real function was of course not mentioned – his carved ivory arm-bangle, and the wooden mirror frame. Sixty-six more pieces remained on a 12-month loan, but all 72 were now property of the Nigerian people.

No good deed goes unpunished, as they say. In March 2023, just four months later, Nigeria’s President decreed that all restituted Benin items are the property of the current, ceremonial and entirely unrepentant Oba, and must be handed to him. The Horniman’s six restituted pieces have not been exhibited to the Nigerian people in any museum and nor have items returned from Germany, from the Smithsonian in Washington and others. Everything is just vanishing. The Horniman has negotiated a three-year extension for the remaining pieces but has lost ownership, and Dr. Merriman has risen above his museum’s blunder and will start work as CEO of English Heritage any day now.

Commenting on last week’s three-year loan of Asante gold regalia to Ghana’s ceremonial king by the V&A and British Museum, the British-Nigerian writer Ralph Leonard wrote for UnHerd:

The sad reality is that ‘decolonising’ Western museums will likely mean repatriated artefacts are to be treated as the personal property of redundant African potentates, rather than the common property of the citizenry of these countries. Should this really be the fate of these cultural treasures?

Both the Benin and Asante empires had slavery as part of their social order and were heavily engaged with European powers in the Atlantic slave trade. Indeed, slavery helped them garner the material and productive base to create their wonderful artworks.

These facts shouldn’t dampen our admiration of these artworks… [which] demonstrate the tragedy that is history and the moral quixotism of trying to make the past ‘right’, especially through the symbolism of cultural repatriation based on nationalist mythology.

We should ensure that the treasures of world culture are accessible to as many people as possible. This means defending the cosmopolitan, encyclopaedic museum that publicly displays the various treasures from different civilisations from across the world in relation to each other, for the masses to see and admire…. To simply ‘return’ these artefacts to their lands of origin would be to segregate world culture. The truth is that all these treasures were formed by human beings, and thus they truly belong to us all.

Which matches the views of the Restitution Study Group (RSG), speaking for millions of black Americans who descend from slaves sold by West African kingdoms, notably Benin’s: the RSG calls for its bronzes to remain in the world’s museums, with captions reminding visitors of their ancestors’ suffering at the hands of one of Africa’s most barbarous regimes. But for the 1897 Expedition, its atrocities would have continued into the 20th Century: a stain on humanity.

The difference between the Asante and Benin kingdoms – missed by BBC coverage of the loan, which yet again predicted restitution of the British Museum’s bronzes – was that Ghana’s kingdom had been relatively literate, advanced and wealthy thanks to its gold deposits, and the British did not find its regalia crusted with the blood of human sacrifices as many Benin bronzes were. In 1897, the Benin regime was still predating on its neighbours, enslaving fellow Africans to sell if possible and otherwise sacrifice to the Oba’s ancestors.

Women slaves were routinely crucified, males decapitated or disembowelled, in numbers which appalled the February 1897 Punitive Expedition. Its reports are reminiscent of Richard Dimbleby’s BBC despatch from Belsen. It was to prevent outsiders seeing this mass murder that the unarmed January 1897 British expedition to Benin had been ambushed and slaughtered. Much has changed in the last year and the public is better informed, even if the BBC isn’t yet. Let us hope no more museums will follow Dr. Merriman’s virtue signalling. We must wait to see what damage he does at English Heritage, and what further promotion will be his reward.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

No mate, no one has to just accept anything! Neither pharmacists nor politicians have the right to determine how millions of people live their lives. You can advise all you like, but that’s it.

People need to start remembering they work for us, we pay their wages. Anyone who wishes to follow their advice should feel free to heed it, but none of them have the right, morally or legally, to force this on us. It is truly time for a political reawakening in the west.

I saw a headline in a Dutch daily earlier today saying that citizens would have to change their lives from now on because of corona. It was behind a paywall so I only saw the headline, but it’s rather coincidental it’s implying the same thing as this person in Australia. It’s almost as if its scripted…

If you’d like to read articles on Trouw, Volkskrant, Parool and NRC websites, even when they are behind a paywall, here is the trick: wait for the article to load completely. Then reload the page with F5, next hit Escape several times before page completely reloads. Et voila: the complete article becomes visible. Sometimes you have to repeat this for it to work, it needs timing. (Unforunately it doesn’t work for Telegraaf website.)

Try this proxy for the DT.

https://12ft.io/proxy?ref=&q=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/

Then once there you can browse around as normal.

Come and fucking make me.

I used to be a polite, respectful person.

But after 2 years of this bollox – “Come and fucking make me” has pretty much become my mindset now.

These c*nts need to re-learn that they don’t own other people’s bodies.

F*** off you drug dealer.

I agree with the head of the WHO.

https://twitter.com/ArtValley818_/status/1473679943045468161?s=20

Boosters also kill adults. Long past tim for the politicians and their advisors to be sent to jail. Many of them though, may well need something more final than a prison cell.

for once I agree with the fact checkers. he started saying “kildren” then corrected himself.

Of course he probably made that mistake because he was actually thinking that they do kill children.

Fancy that, somebody pushing a policy stance which will provide another cash cow for his industry. I am surprised some of these thick journalists can actually read and write, let alone considering issues such as conflicts of interest when choosing who to interview.

Never ask a barber if you need a haircut…

It’s beginning to look a lot like genocide.

Excellent, that should have been Christmas no.1

Do they know it’s Genocide at all.

That’s a very fair assessment and genocide brought to you by your own government.

Has this individual done a proper risk benefit analysis of a twice yearly vaccine?

Eg, a few months ago the JCVI decided that the risks of the vaccine were greater than the benefits for those <18 (obviously this was overruled by non-experts in vaccines). This was based on having two doses. I’d presume that if they knew that a 16 year old would have 10+ doses by the time they left college the risk:benefit analysis would be firmly on the side of risk.

This is doubly true now that the risk of covid appears to be diminishing rapidly, as is the effectiveness of the vaccines.

I also wonder where this expert got their understanding of the effectiveness of mask wearing — ‘science’ says that they don’t offer any substantial protection.

The people pushing these policies are not incompetents they are high level criminals. criminals

Besides your comments on this, I have not seen one single reference made to what should be an obvious point.

Continued administration of any medical product carries risks, what are these risks, are they cumulative, etc. This should apply doubly to a completely new technology that is being applied, triply when the illness being tackled seems to be becoming less of a threat by the day.

It’s just not, and we won’t.

I really can’t stand any more of these idiotic people. With apologies for the language – this guy is a fucking moron. Just put the the cunt up against a wall and shoot him.

Can’t fault any of that. Precise and well thought out.

US Marine style – shout, show, shove, shoot.

With each new jab, less people take it than the one before.

This guy isn’t going to get his wish. The more they push, the more people will wake up and the fewer will take the next jab.

How does he account for the fact that the vast majority of the existence of mankind, we didn’t have vaccines and yet we didn’t become extinct?

I would hope that’s the case but what if they keep rolling out new ‘variants’?

Further proof of criminality.

‘But now we have the vaccines, and we have to take them, to guarantee health…’ is his dislogic.

It’s a shell game, with transparent shells, and punters still losing every time!

One should hope.

…then again, I don’t do hope.

What legitimate authority does this SS Dentist have over Australians or anyone else?

Isn’t what he is saying really that he want to make ‘loadsa money’ year on year out of a coerced and terrorized population, as medical capitalists dictate obedience and reap billions?

Time to form independent medical bodies to safeguard the real health interests of ordinary people, and ignore diktats from tools of Satan.

How are the Australian death camps doing?

How about every Australian has to give up a kidney as well?

What exactly was it that first attracted you to the multi billion dollar vaccine industry, Mr Twomey?

What a fucking tool! Not a shred of science…simply do as you’re told. This guy has zero authority and should shut his trap.

Australia is lost.

A Mad Max future is still a future of sorts!

In retrospect, Mad Max was optimistic.

Disgraceful hysterical extremist with a fetish

Trent Twomey, the National President of the Pharmacy Guild in Australia

There’s the clue, right there in the first line.

‘Stick this in your arm every 6 months, and I get to buy a beach-front mansion in Noosa’.

Over TWO winters……Australia’s C-19 mortality is 2,173…..they won’t reveal the profile of those who have been taken.

VIC…….1,476

NSW…..648

ACT……15

TAS……13

WA……9

QLD……7

SA……..4

NT…….1

Quite clearly, there is broad NATURAL IMMUNITY in the whole country.

Wouldn’t it be cheaper, more efficient and more lawful if instead of jabbing the whole country, they tested everyone for immunity?

Or just abolished the entire shaet show and then shot the shites.

No masks, tests or vaccines needed. The figures above amount to little more than a mild cold. Twomey is part of the Gates criminal conspiracy to depopulate and control the few that will survive the 5G sensitive nanotech “poison death shots”.

Nothing can beat the immunity created by the Wonder vaccines!!!!

This should be the case in every country – the UK included. It’s vital and valuable data but it doesn’t fit with the tunnel-vision vaccine agenda.

Not really a suprise. These people are deranged

Never had one, will never have one. Model that Cobber.

The Premier of NSW and the PM have rejected mandates for masks and vaccines.Try again, numbnuts.

Go Fuck yourself Trent.

President of Australian Pharmacy Guild says that people MUST accept a drug that Big Pharma make huge profits from……..well, he’s not stupid is he? But he also thinks that we are.

The full vaccinated will never be fully vaccinated…..

……..yet nobody knows what continued jabbing will do to peoples’ immune systems.

Its like those books we read as kids with mad scientists (trying) to rule the world

Just like the flu, if anyone wants periodic jabs be my guest. This fight is about mandates and digital passports

I’d actually encourage the former.

The sooner we will be rid of the most fanatic ones, like him.

My sister-in-law is a senior pharmacist in the UK, good at what she does but is incapable of independent thought or reasoning, and I absolutely would not take any kind of health advice from her at face value.

She is currently ill with ‘covid’ after three jabs, but dots have most certainly not been joined, no sir.

Sorry to hear that. Like millions, she is probably brainwashed to never flinch at the prospect of dozens of vaccines still to come – with neither one ever ‘working’.

God help us all.

Alas, for her they are working.

She obviously would have been twice as poorly without them.

Doh!

Alternatively, you can accept you have to sniff the hair of an agitated honey badger.

Maybe we could agree to accept it on the understanding the pfizer publish all details to do with the vaccine trails and also that the vaccine manufactures agree to take full financial liability for any adverse reactions. If they do not trust their products enough to do this then why should we put them in our bodies.

I think Pfizer trust them to do what they are meant to do. They just don’t want the public knowing what that is.

Meanwhile, just to prove there are sane people in Australia, the resignation letter of a Queensland doctor, forced to resign by political fascists after 41 years for reasons of bureaucratic madness:

https://cmnnews.org/story/letter-from-a-doctor-to-a-health-minister-T7iSvHSp3c1aADxdwCvoD

That’s a beaut of a letter.

A brilliant letter!

Good! We always said and knew that all of this stuff was going to be forever, so the more openly this is made clear, the better, as it will wake more people up.

The problem people have understanding what is going on, is their continuing naive belief that national governments control the agenda. They don’t, haven’t for some time.

Its an alliance of big finance, transnational corporations, tech and bio-tech under the umbrella of organisations such as the BIS.

The control is not classical command structure, its far more nebulous. There are no ‘heads’ to cut off. Its much more an alignment of interests. But make no mistake these lose affiliations control the world.

They have seen an opportunity even dire need to reinvent the capitalist financial models after 2008. They have endured a couple of resent setbacks; Brexit and Trump. They decided that the general dumbing down and messaging of the western nations had proceeded to such an extent that a suitable ‘enemy’ could instill enough fear to bring about the necessary social changes that ensured a runway to installation of the totalitarian state necessary to manage the ‘reset’.

The timing of omicron ensures that ’28dayPCR’ rule will bring increased reported deaths, however mild the variant might be. This will get them over the final hurdle of mandated vaccinations and the ‘passport’ which is the bio-ID required for control as it expands to cover all aspects of what will pass for ‘life’.

I share people’s desire for optimism, that omicron will prove the turning point. If it was really about health and it had just been bungled from the start our optimism is well founded.

However in the words of my current favourite Scot ‘ Its not about what they say its about’ and for many the final confirmation of that is shortly to happen.

All those above saying Australia has gone mad, do you really think the same thing won’t be rolled out everywhere else? How else are they going to justify their passports and why do you think they’re currently going nuts over boosters here?

But thankfully the propaganda juggernaut is appearing to derail elsewhere.

I posted this on the daily update page a bit earlier about Portugal:

“Despite being vaccine leaders and over 83% of their over-65s boosted, it appears Portugal is reimplementing harsh restrictions:

https://www.portugalresident.com/omicron-wave-portugal-plunged-into-morass-of-new-measures/

The positive note is how balanced, if not sceptical, the article is.

Only a few weeks ago it probably would have been censored and labelled conspiracy-theory material.

We’re starting to see some progress people!”

And as you may already be aware, over here we’ve got the likes of bedwetter-in-chief Owen Jones suddenly realising that perhaps lockdowns & restrictions are not such a good idea.

Owen Jones; I remember his name. Must have read some of his articles years ago.

Apparently Bruce McScrotum of the Australian Used Car Dealers Association said that it’s quite clear that every Australian citizen has to come to terms with having to purchase a used car every six months .. there are no other options

Just think it was about this time last year that the pig dictator was vomiting out the lie, a vaccine is available and once the vulnerable are vaccinated we can return to normal. Happy anniversary bedwetters, book your 4th jab when you have your 3rd.

Or maybe Trent Twomey will need to accept being carted off to a dung heap by a pitchfork-wielding mob. He’s playing a high stakes game with his crazy ass announcements for sure.

Trent, Could I see the long-term data on having multiple boosters over a prolonged period of time of this so-called “vaccine” please? Oh, there isn’t any is there? As a fit and healthy adult in his 30s – who has recovered from COVID-19 – with two dependents, I think I will not take part in that experiment thank you. Last time I checked, I lived in a liberal democracy not a totalitarian state (although we have been heading that way and time will tell if I am mistaken) so I do not have to “just need to accept” your nonsense.

Meanwhile in Denmark:

“”There’s something antigenic in Denmark: boosters show negative vaccine efficacy for cases”

vaccines, including boosters are showing strong negative efficacy vs omicron

this is consistent with omicron being as OAS enabled escape variant

omicron continues to show evidence of mildness relative to past variant

https://boriquagato.substack.com/p/theres-something-antigenic-in-denmark

What he needs is a swift kick in the Bollocks !!!…

Wow, Trent must be going for the biggest brown envelope of all from his NWO & Big Pharma overlords.

Just reverse the Shute formula and nuke Australia.

…it’s the kindest thing you could do for the incarcerated, there.

Just. Say. No!

I used to fancy an extended holiday in Australia and NZ. You couldn’t pay me to go there now.

When such jabs provide less and less benefit (and the immune response has declined with each dose), the costs will be noticed and debated. There will also be more and more evidence on T and B cell instead of antibodies as the key to Covid response.

Might such booster still be “required” for those over 60? Sure, not that it will be enforced. In the end they can’t keep Covid fear going forever and as it slips away, people simply won’t comply.

Ivermectin help reduce the severity of vaccine adverse reactions. If someone is suffering from a post vaccine syndrome, FLCCC clinicians and a growing network of colleagues have reported significant clinical responses to ivermectin. Because Ivermectin has 5 different mechanisms of action against coronaviruses, the medication is also effective with the different variants of the virus. Get your Ivermectin while you still can! https://ivmpharmacy.com

Trent, the Covid Gravy Train is closer to the end of the line than you can imagine.

I’m so so glad I’m not Australian. I thought I was living in a madhouse.

It would appear that descendants of the Nazi hierarchy moved to Australia as well as South America!!