Last week, my Substack page News From Uncibal got its 500th subscriber. It is therefore fitting that I should return to the subject which got the whole thing started: Gary Lineker, and his semiotic significance. Lineker ought to be an obscure figure. But he is central to the national debate in Britain, and it is important to make clear why, as he symbolises much of what is wrong with the way things are going – not just across British society, but across the Western world.

How does one explain Gary Lineker to a non-British reader? Lineker is a former professional footballer with a natural poacher’s instinct for goals, who won the ‘golden boot’ at the 1986 World Cup finals and was for a time probably English football’s leading light. He was also famously ‘nice’, having never received a yellow card in his entire career, and he gave off a wholesome, schoolboyish vibe, leavened by a slightly impish charm. After his playing career was over he made a living as the face of Walker’s crisps, a snack company, appearing in a long-running series of humorous TV adverts, and he eventually became the presenter of the Grand Dame of BBC sports coverage, Match of the Day (MOTD).

MOTD, like everything on broadcast television, is a shadow of what it once was, but it still has totemic significance in the national psyche, being screened late on a Saturday night and featuring highlights of the day’s football punctuated by chunks of easily digestible ‘punditry’. The person who presents the programme therefore ends up occupying a position a bit like the captain of the English cricket team or a prominent soap star; people feel as though it matters in some profound sense who has the job.

Lineker is by some distance the most highly paid figure who works for the BBC (though he is technically not an employee), earning something like £1.3 million a year – which he gets basically for sitting down once a week to ask easy questions to former footballers with respect to some football matches that happened that day (and also cackling and braying along to Alan Shearer and Micah Richards’s ‘jokes’ – I use the term loosely – on the appalling Match of the Day Top 10). And this is where the trouble, for most people, begins.

I have no problem, for the record, with people earning whatever amount of salary the market considers to be appropriate – I am not the kind of person to get excited by the issue of fat-cattery in the round. But the important thing to understand about Lineker’s salary is that it is not the product of market forces, because the BBC is not subject to those forces (except indirectly in the sense that fewer and fewer people choose to watch BBC TV programmes). Indeed, every single household in the U.K. which owns a colour TV must – at pain of criminal sanction – pay the BBC £159 a year for the privilege if it intends to watch, or record, broadcast transmissions. It is no exaggeration indeed to say that the great majority of the population of the country is forced by the criminal law to pay a portion of Lineker’s salary – something about which they have absolutely no choice (unless they do not wish to have a TV at all), no control over and no recourse to appeal.

As Kundera once put it, sometimes in life it is the most banal observations that shock us the most, and this is one such instance. Unelected bureaucrats at a taxpayer-funded media company have mandated that a former footballer be paid vast sums of money at public expense in order to front a TV programme that individual members of the public may or may not even watch, with each of them being forced to comply on the basis that if they do not, they will have to pay a fine of up to £1,000 (or be imprisoned).

And we have the nerve to call Tajikistan, Myanmar and Eritrea corrupt.

This should of course be scandal enough, although when it comes to the TV licence – as with the NHS – the British population suffers from a strange variation on Stockholm Syndrome, in which great outrages are forgiven and indeed welcomed on the basis that they are ‘our’ great outrages and we all have fluffy and sentimental associations with them. And if Lineker was able to restrain himself to simply reading out football scores and remarking on how good player X, Y or Z is at finding ‘pockets of space’ and how a particular tackle ought to have been a ‘stonewall penalty’, he would fly completely below the radar and could enjoy his sinecure in peace until he shuffled off the mortal coil.

But of course he is on Twitter (or X, if you prefer). And, like anybody who ends up on Twitter, his brain has been well and truly borked. But it has been borked in a certain, illustrative way. And this has allowed him to take on a role as a public figure whose views on The Current Thing are taken to be of great import by significant chunks of the ‘new elite’. This, naturally, draws the ire of people who tend to disagree with his views about The Current Thing. But it also gives us a window onto a particular character type, very common among the media classes, and highly detrimental to sensible public discourse.

Keen readers may choose to take a break for a moment and listen to Gary Lineker’s 1990 appearance on the BBC radio interview programme, Desert Island Discs. For those unfamiliar with the format, Desert Island Discs involves a public figure of some kind being interviewed by a friendly journalist and being asked to choose his or her favourite eight records of all time, and commenting on what they signify. In Gary Lineker’s case, the records in question, instructively, are about the most anodyne that can be imagined (the most outré is Booker T & the MGs’ ‘Soul Limbo’, for heaven’s sake). But the music isn’t very important here. What is important is the interview itself, which reveals very starkly that Lineker is not the kind of person whose views it is important to take seriously about, well, anything other than football. Because, basically, he just isn’t very bright.

But the thing is, he is bright enough. Reading through his timeline on Twitter, one is struck by the same observation, time and again: this is a person who is not really capable of rigorous thought, but is intelligent enough to identify the right thing to say at any given moment in order to appeal maximally to bien pensant Twitterati with regard to the issue of the day. Here he is, for instance, on Nigel Farage, at the time of the Brexit referendum:

And here he is having a go at Boris Johnson after the English national football team made it to the World Cup semi-finals:

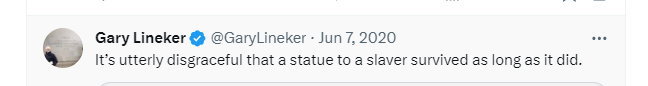

Here he is on the removal of the Edward Colston statue during BLM protests in Bristol:

On Covid school closures:

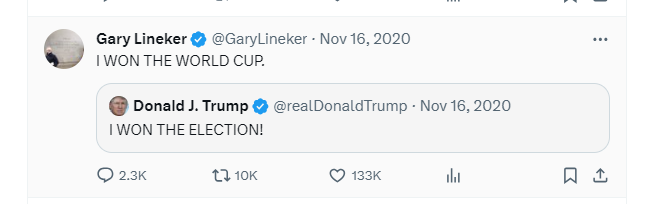

On Donald Trump:

On gun control in the USA:

And finally on Suella Braverman, who spoke recently to condemn mass marches taking place in London in support of Hamas:

Notice how finely tuned are his antennae. How he casts around for exactly the right line to tack with respect to whatever item is on the news agenda, to discern opinion amongst the James O’Briens and Alastair Campbells of the world, and to chime in with an observation accordingly. This is not a man who forms opinions; it is a man who imbibes them from people whom he thinks to be educated and intelligent – the clever people he follows on X – and then simply repackages them as his own. He spouts platitudes, but they are finely distilled platitudes – precisely the right kind of platitudes to garner ‘likes’ and retweets, and generate an ever-growing following. His brain, I repeat, has been borked, and now it functions in an almost purely Girardian way, as a kind of relentless pursuer of mimetic status via social media.

What we have in Lineker then, is a particular spectacle, unique I think to our cultural moment, in which a man who has no discernible applicable talent when it comes to political affairs, and is not really capable of forming independent views, let alone critical analysis, is given a platform by dint of the fact that he has been selected for a role by unappointed bureaucrats, from which the electorate cannot eject him. And he uses this essentially to signal his own adherence to the high-status causes of the day, and thereby cement his own position as a kind of public defender (or launderer) of the views of the higher echelons of society. People like this have presumably always existed, but our age is characterised by their prominence – and indeed their centrality in the public square. And Lineker is in this way highly representative of the Vanity Fair-like tenor of public life in the 2020s, with its apparent lionisation of hypocrisy and superficiality and a concurrent debasement of our public life.

This is in itself obviously to our vast detriment. And this is not even to speak of the demoralising effect it has on a population to go through life having to know what people like Gary Lineker think – to have it printed on the front of newspapers and talked about on the radio and otherwise insinuated into one’s awareness despite the fact that it is inevitably ill-thought through, bland and obvious. That cannot but have negative consequences for our ‘lifeworld’, in the same way that being made to eat nothing but Walker’s crisps every day would eventually have serious consequences for one’s endocrine system.

But the rot goes much deeper than that. Because, of course, the most profound problem concerning the Gary Lineker phenomenon is that he represents, in microcosm, what is going on inside most people’s heads nowadays. Something about the incentive structure of the internet and the innate frailties of the human character combine to turn us all into mini-Gary Linekers much of the time: slovenly dilettantes, knowing very little about very much at all, imbibing our views magpie-like from whatever online loudmouth happens to grab our attention, and convincing ourselves that our opinions are worth airing and taking seriously. The result is a peculiar mixture of breeziness and fanaticism: everybody utterly convinced that they are right and that anybody who disagrees is both wrong and wicked, in inverse proportion to how much they actually know (or really care, deep down inside) about the issues involved.

We are not as bad as Gary Lineker, because we do not behave in the main as if it is holy writ that we should be lavishly funded by a hypothecated tax in order to have a platform to air our oafish views. But we are infected by a repulsive and self-aggrandising Linekerishness all the same. Where we go from here is anyone’s guess. What does Government look like when the population is increasingly comprised of slovenly dilettantes, as I earlier called us, who are incapable of reasoning and know almost nothing about the world but are utterly convinced that they are right about absolutely everything? One thing at least is for sure – we are on our way to finding out.

Dr. David McGrogan is an Associate Professor of Law at Northumbria Law School. He is the author of the News From Uncibal Substack where this article first appeared.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

The UK fascist Deep State has been, for some time now, at open war with its citizens.

A BANANA republic.

MURDERING its own citizens and placing them under SURVEILLANCE for their legitimate political opinions.

Is your hand approaching that red pill yet Toby?

The UK played a large part in the now admitted fake Russian collusion plot used to hamstrung Trump during his time in office.

Projecting our ‘soft power’ on the world is just another word for deep state shenanigans.

Why do you think our foreign aid contributions is such a big deal politically ?

Let’s see some deep dive articles on foreign NGOs and what there real purpose is.

Let’s have an article from Venessa Beeley regarding Syria for starters and the dodgy UN white helmets.

A measure of caution may be advisable here.

There is a great deal of (understandable in what has become a ‘democratic’ socialist fascist state) paranoia about.

I myself have often been accused of ‘belonging to the 77th’. They may be desperate, but I think not that desperate…..

The ‘whistleblower’ states the following:

‘We were told what was legally allowed – such as ‘scraping’ online platforms for keywords – and what was illegal. This included repeatedly looking at a named UK individual’s account without authorisation, although some people would do that from their own accounts after their shift.

We would take screenshots of tweets from people expressing dissatisfaction with the UK Government’s action against Covid. The project leader would then gather these screenshots and send them to the Cabinet Office. Feedback from the Cabinet Office would direct us over what to look for the next day.’

So looking at a named individual’s account was briefed as being illegal, but individuals did it using their own email accounts off duty……

‘Feedback from the cabinet office would direct us’ is also a curious form of words.

He goes on to say: ‘We learned from the feedback that the Government were very keen on hearing what the public thought of their Covid response.’

That sounds more like a statement of the blindingly obvious than ‘direction’

The perspective is, of course, that we know the Russian ‘Internet Research Agency’ owned by Prighozin, who also owns the mercenary Wagner Group active in Ukraine, constantly attempts to subvert public opinion in this country and elsewhere via social media. We know this because his employees have told us so:

‘The expectation, he said, was he would make about 120 comments during his shift.

The “factory” had many different departments, each comprising around 15 people and each dealing with a different external Internet or social-media company. One dealt with YouTube, he said, another with Facebook’

‘Sometimes “trolls” would be expected to respond to another “troll’s” comments or post, to give the appearance of a discussion involving two unconnected users, he said.’

Sergei K. (Retired Internet Research Agency employee)

So ’77 Brigade’ could, wholly appropriately, investigate comments on all manner of websites, threads, in this country quite possibly emanating from St Petersburg.

In fact I am delighted if that is indeed what they have been up to…..

this is what is called a non denial denial

If I may, “A measure of caution may be advisable here.” Absolutely correct, as with everything you write, in fact, “…a statement of the blindingly obvious”

So are you claiming that the likes of David Davis MP, Julia Hartley-Brewer, Peter Hitchens, Toby Young and various other high-profile dissenters were secretly working for the Russians, or were suspected of secretly working for the Russians?

Pathetic justification for the Government spying on citizens who were simply questioning whether our Civil Liberties should have been demolished over a ‘flu bug with a mortality rate of 0.2%.

*deleted* by me. Replied to wrong post.

No.

You clearly have not read the Big Brother Watch report.

I am saying that all the ‘whistleblower’ has revealed is that ’77 Brigade’ was tasked with monitoring misinformation from foreign sources on Twitter but that some servicemen may have monitored British citizens Twitter accounts using their own private internet accounts whilst off duty.

If they were using service equipment to do that, they will almost certainly be charged.

Wow. 150 downvotes! Sergei K and his commrades must be on the wodka again.

No doubt they are now equally busy spying on anyone opposing the proxy war in Ukraine as well.

Bet “Monro” is all up for that.

on steroids. The payment to house ukranians is classic spi-b. Never happened for any other group.

Who are these people? Again we’re forced to ask who they’re ultimately working for. So the MOD through this secretive 77th Brigade (though only known to some of us, I bet my aging Dad has never even heard of 77th – let alone SPI-B and Mindspace) says they’re deploying ‘non-lethal engagement and legitimate non-military levers as a means to adapt behaviours of adversaries’. As a British citizen I didn’t know I could even be a potential adversary, but if voicing our concerns is considered adversary (enemy / foe – that’s what the thesaurus says) how should I consider them in return?

They are not secretive:

https://www.army.mod.uk/who-we-are/formations-divisions-brigades/6th-united-kingdom-division/77-brigade/

Their barracks has an enormous coloured sign outside it displaying their emblem.

They are tasked with all this stuff:

Now, if the designated task is dodgy, that is the responsibility of those doing the ‘tasking’

If they wished to operate ‘in the shadows’, probably targeting Hitchens and David Davis, Toby Young, was incredibly dumb, but, in that case it sounds entirely plausible that they should have been so tasked……by the dumbest government, in a tough field, that this country has ever had………

And, if they were so tasked, there will be an email trail that Messrs Young, Davis and Hitchens should be entitled (and will demand) to see, even if it takes a court/public enquiry to order the release of that trail……

That would be interesting…..could be ‘phone hacking’ 2?

With respect I think you missed the point of my post. It’s clandestine in its very nature, but I’ll endeavour to forward this info to my Dad, try and explain the psychological manipulation he’s been under, describe how British Citizens (we don’t really know who, do we) are being monitored and manipulated by our own government and army.

You are entitled to your opinion.

Your father, though, could have spotted that from reading the newspapers. I know of two, at least, that covered the ‘nudge’ in some detail.

Unfortunately many, if not most, just didn’t want to hear it, for reasons that I have never been able to fathom.

Two instances? I wouldn’t call that being informed though, despite it hiding in plain sight – you’ll only know either by pure chance or by those independent journalists standing up to be counted and who agree with the concept of a genuine free press (those who’ve likely been targeted by this 77th because someone arbitrarily regards it as dangerous misinfo).

Through the government’s mouthpiece, the MSM, we were informed of our government partaking in a campaign of public safety (supposedly) but weren’t being told of their simultaneous nudging techniques (known to us now yes, but to no one at the time) to increase fears (almost to the point of irrational), whilst pumping them full of injections (let’s not forget that) which have turned out to be far more dangerous than thought. The whole informed consent ethos is already on thin ice, if we’re to include the psychological manipulation whilst any public dissent of that manipulation is being monitored and countermanded in real time, this whole approach is remise of any ethical standards at all in my opinion – grooming the naive into taking experimental pharmaceuticals they neither wanted or needed (anecdotal, but most people I know have regretted it since learning this backstory).

A two minute search shows at least five different newspapers have covered ‘nudge’ techniques used during the covid debacle. There are myriad other academic papers etc covering the same topic.

Government ‘nudge’ has being going on for years encouraging people to eat eggs, drink milk, not to eat eggs, not to drink milk, all a complete waste of taxpayers money and extremely annoying.

You have your own opinion. What makes me at best extremely disappointed in the majority of my fellow citizens is their supine subservience to what is now called nudge but was in fact a crass and obvious, so, to me at least, implausible, and profoundly silly ‘covid’ public information campaign.

Granted, they’re consistently campaigning various projects behind the scenes from healthy living to social justice and have been ongoing for a long time, but these are what I’d consider public campaigns, not this nefarious behavioural nudging to the extent we witnessed during covid.

At the risk of repeating myself, once the government is openly admitting to an intervention strategy via a public campaign (to keep us safe), their hiding the existence of running a concurrent fear campaign beneath to justify much of the public one is purposefully misleading people – most people thought they were being informed, not manipulated at the same time.

Whilst making sure the exposure of this manipulation never gained the critical mass of awareness to affect change via this 77th division quashing dissent and perhaps even partaking in censorship? I don’t know if they actually did that but nothing would surprise me at this point – though one could argue their direct manipulation of this dissent lead to a similar outcome. Anything contrary to the narrative was deemed harmful – oh, the irony.

I too am disappointed more people didn’t see through it but most didn’t know they were under attack by their own government, they just wouldn’t expect or even believe it (whilst hearing on every broadcast they’re doing everything to keep them safe) so breaking them free from this mass psychological formation is going to be a huge task.

Regarding the monitoring of British citizens, what we do know is:

‘We were told what was legally allowed – such as ‘scraping’ online platforms for keywords – and what was illegal. This included repeatedly looking at a named UK individual’s account without authorisation, although some people would do that from their own accounts after their shift.’

So they were not authorised to monitor any named UK individual’s account.

They did that using their own personal accounts out of hours without authorisation.

That may or may not be actionable. I have no idea.

There will be an accountable trail for any named UK individuals they were authorised to repeatedly look at. So we will know who those were in due course and if that monitoring was inappropriate, as with phone hacking, heads will roll….

It is no more acceptable now than in the 1930s snd 1940s to say”I was only following orders”. The British Army must behave within a democratic environment or the consequences will later be sever.

we were much too lenient to the German Army and bureaucrats in the late 1950s but we will not repeat that for our own.

Yes, but were they following orders?

‘We were told what was legally allowed – such as ‘scraping’ online platforms for keywords – and what was illegal. This included repeatedly looking at a named UK individual’s account without authorisation, although some people would do that from their own accounts after their shift.’

Those engaged in ‘unauthorised mission creep’ may very well regret it.

The problem is that in the UK we don’t have the fruit of the poison tree legislation that exists in the US. The result is that illegally obtained information is usable in court, this is clearly a bad thing because it means that convictions can be made on evidence obtained by questionable means. That leaves a stain on the legal system and should not be permitted.

Fortunately, in Messrs Young, Davis and Hitchens we have three splendid individuals who are very unlikely not to get to the bottom of exactly what has been going on here, how to remedy it so that it never happens again.

At least, then, some small good may come out of the grand stupidity that was this government’s response to the simple emergence of just another common cold coronavirus.

This is only surprising and disturbing to someone whose worldview is that the state and the government are trying to do what is best for the general public.

If, like me, you see the establishment and the government as a series of self serving rackets, then you’re shrugging your shoulders.

I have no doubt the establishment has people monitoring the DS (among other sites like it).

Wasn’t Tucker Carlson actually attacked by the US establishment for being a Russian agent (and was tipped off by a friend in the establishment before it happened)?

If by Delingpole is meant the thesis that much of the totalitarianism is wilful, the answer must be yes, he has been right all along. The UK is almost a clone of what is going in the US, and from research such as The Real Dr Fauci – a dense must-read – it is clear that the State has been increasing its own subversive, anti-democratic, anti-liberal powers for decades, since before 9/11.

No one with any sense is surprised…it was obvious during Covid, not least from thousands of ‘Tweets’ which re-iterated the same Governmental propaganda word for word…and I’m fairly sure we had some on Sceptics and on comment pages in the MSM during the height of the scamdemic….the comments were just too similar to be random…..

the (dis) information lock-step, I’m sure, involved most Western countries..

Through the brilliant reporting of Matt Taibbi and the Twitter files…..the public has been made aware of the involvement of Governments, their Agencies, Senators the FBI, CIA, and I’m sure the equivalents in many countries …and the lengths they will go to to lie, deceive, misinform and propagandise the public, just so they can control the narrative…..the uncovering of the Russia-gate files…a total fabrication of the U.S Government…is a good case in point.

In this instance I truly hope people are identified and held to account…

I look forward to reading the full report….

I would just point out the Wiki entry for that obnoxious creep Tobias Ellwood.

Tobias Martin Ellwood VR (born 12 August 1966) is a British Conservative Party politician and soldier who has been the Member of Parliament (MP) for Bournemouth East since 2005. He has chaired the Defence Select Committee since 2020 and was a Government Minister at the Ministry of Defence from 2017 to 2019. Prior to his political career, Ellwood served in the Royal Green Jackets and reached the rank of captain. He transferred to the Army Reserveand has gone on to reach the rank of lieutenant colonel in the 77th Brigade.

To be hoped his constituents see sense and do the right thing by dishonourably discharging him from duty in 2024.

Wikipedia

Tobias Martin Ellwood VR (born 12 August 1966) is a British Conservative Party politician and soldier who has been the Member of Parliament (MP) for Bournemouth East since 2005. He has chaired the Defence Select Committee since 2020 and was a Government Minister at the Ministry of Defence from 2017 to 2019. Prior to his political career, Ellwood served in the Royal Green Jackets and reached the rank of captain. He transferred to the Army Reserveand has gone on to reach the rank of lieutenant colonel in the 77th Brigade.

Judging by the below-the-line comments on the Mail’s article right now, the usual ‘disinformation’ mob from 77th Brigade are busy attacking the article.

I’m not surprised. We knew the people posting below the line on comments on the Telegraph were 77th Brigade and other state operators. They used the same scripts, made the same arguments and used the same insults. They would also all turn up at an exact time. Often, it appeared the same person would have several Telegraph accounts open in more than one window on a computer and be talking to himself across different IDs and upvoting himself. There were a few ‘gotcha’ moments where the posters would use the wrong ID.

The British state has fallen. We all knew it. We’re all probably in dossiers somewhere now! This news confirms it. To think – excepting the alien invasion bit – The X-Files turned out to be right more than it was wrong!! 😀

As a child of the 60s, ww3 has NEVER been closer!

I think we are well into WW3 !

Is it just me or does the 77th Brigade seem to get a lot of MSM attention for such a “super secretive” unit?

Considering their entire remit is information warfare, I doubt this ‘whistleblower’ is anything but another clever (or not) ruse.

Semantics. They aren’t a secret organisation: how they go about things is secretive, although, as is the case with everything in our repressive modern day society, from 77th Brigade to the WEF and Soros, they aren’t competent. You could spot 77th Brigade a mile off online. The WEF show off about all their alumni getting into positions of power, but the real legacy of the WEF’s alumni has been COVID-19 lockdowns and trashed economies. George Soros is famous for funding elected legal officials in the US and his favoured candidates are remarkable for how bad crime becomes on their watch. Larry Fink and BlackRock are proud of ignoring the fiduciary duties of maximising profits for shareholders, allegedly to save the environment, but the people for whom BlackRock invest are beginning to notice they’re losing money hand over fist.

Perhaps that’s the biggest thing that will ultimately bring down the new oligarchs and the new globalist authoritarian surveillance states: they’re all very good at getting into positions of power, but once they get there and once the light of public scrutiny shines on them, people quickly realise they’re crap at their jobs!

Does it seem weird to say I’m pleased to read the findings of this report? There have been times in the last two or three years that I genuinely thought I was going mad (or everyone around me was mad and I wasn’t!) I would talk to people online and wonder how it was that our very middle-of-the-road opinions on liberty were being treated as dangerous thought crimes; that Mike Yeadon, an expert in his field, was being called a ‘dangerous fanatic.’ That libertarianism was repeatedly being associated with the ‘far right’ even in the mainstream press. That 77th Brigade posters repeatedly referred to ‘far right libertarians’ in comments threads in the likes of the Telegraph (which was receiving funding from the B&M Gates Foundation until last February, assuming they haven’t taken another grant.)

I’m not even angered by this report: I’m relieved. To get confirmation that all my worst fears were real is strangely liberating. I feel like I can move on now.

I’m a subscriber to the UK Daily Telegraph website, and used to leave comments there…before I was banned…

Commenters often suspected members of 77th Brigade were making comments on the various Covid related articles, interfering with general discussion.

The Daily Telegraph receives funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which may skew its reporting, particularly on matters related to vaccination policy.

I was banned from commenting on the Daily Telegraph because I raised the matter of conflicts of interest of Andrew Pollard, Chair of the UK Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation, and also the Chief Investigator on the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine trials. The JCVI website says Andrew Pollard “would recuse himself from all JCVI COVID-19 meetings”, but I don’t think he was ‘recused’ when the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine was getting off the ground in January 2020?

I suggest this is a matter of public interest, but not according to the Daily Telegraph, which sought to suppress transparency for Andrew Pollard and his conflicts of interest.

No surprise, sadly. Evidently the Telegraph has continued its association beyond the original grant term which ended last year. I’ve ended my lifelong association with the paper. My grandfather, who retired in the 1980s, was a major writer for them from the 1950s. He’d be appalled. I miss some of the columnists, but there’s as good elsewhere now. The Telegraph has been going in the direction of the Grauniad for several years. As far as I know, it’s still on the market. That no one’s bought it is telling.

An excellent decision if I may say so. I too terminated my association of some 30 years with the Telegraph during Covid when I learnt it had become Bill Gates bitch.

The DT had their own 77th brigade called Adam Hill…. Remember him?

Yes I do indeed remember Adam Hill…mad as a cut snake…🤣

Yes, I jousted with Adam most days, particularly over his use of the term ‘far right libertarians’. Indeed, I might have given away my real name by saying that!! 😀

Agree fully with your comments. Do you still subscribe?

Yes I do.

Unfortunately I have to subscribe to keep an eye on how they’re trying to influence policy.

Do the same with the dire Murdoch media in Australia.

I yearn for the day when the wretched ‘mainstream/corporate media’ is completely sidelined.

Hope this is in progress now, with people moving to alternative media.

This needs to be raised in Parliament where that barefaced liar Sunak can deny it..

I’m not in the least bit surprised to read this. They’ve been building a Surveillance State for well over a decade and the surveillance went into overdrive during the Covid lunacy.

I’ll be surprised if the spying was only limited to a relatively small number of high profile people, I wouldn’t mind betting that even “ordinary” dissenters were being monitored.

This country’s getting more like East Germany with every day that passes.

Still, it’s progress if Toby is starting to wake up and accept that none of this was “cock up.”

In the UK, the modern surveillance state really started with John Major. I recall reading somewhere that by 2000, the only countries that spied on their citizens more than the UK were China and N Korea.

Hammersmith, I believe, had several hundred surveillance camera and represented the the most surveilled area in the world. When I mentioned this to a couple of the youngsters (early 20s) in the place I was freelancing in Hammersmith, when I was in my 30s, they were shocked that I had a problem with the surveillance. ‘If you aren’t committing a crime, you have nothing to worry about,’ said the girl. The boy looked at me like I was mad for questioning it. The USA probably would be as bad, but the infrastructure to do so in the USA simply isn’t there in many areas. But if you live in a big city, the surveillance is probably obscene.

When the NHS gave up bothering me about clot shots – the letters and text messages dried up – I’m sure I was put on a database somewhere as a potential ‘subversive’, along with my comments on the Telegraph and on here being catalogued. COVID-19 has put in place an infrastructure for future lockdowns and easier state coercion. It has also shown the state who the ‘awkward squad’ are and doubtless we’ll be the ones targeted to be shut down immediately they launch another virus.

The surveillance is easier than one would think. We already know that all electronic data is legally stored “to prevent terrorism,” and Snowden showed how easy it was to harvest that data from everybody. If it’s illegal, they can just get the US or Australia to do it for the UK by the Five Eyes arrangement, and vice versa, and then share the data… or do it anyway and plead “national security” to prevent disclosure. Or bypass the law by passing on the data to private companies before erasing it, and then using the companies as “consultants.”

Put the data through AI to pick up keywords that would be used by “people of interest,” just as you would for terrorism-linked words, and on that same dataset collate anything that might be used to intimidate them – porn sites, financial irregularities, or even private “hate speech.” A few million ordinary people then have automatically-produced dossiers in electronic form. That would label most of the low-level dissidents.

If an individual achieves a sufficiently high profile to be of “interest,” ie worth suppressing, then for the first time a human is assigned to access the dossier (and no doubt all associated electronic data) in order to cancel (the more benign option) or blackmail into silence.

All they need is a modest number of human staff, plus data access, AI and a lot of data storage – and for that there is GCHQ. There is no need to have an army brigade scouring social Media and the web for disinformation – one can start with everyone and filter it down algorithmically.

Apparently, the 77th Brigade are short staffed because they’re all off with Long Covid 🤣🤣🤣

Again we see evidence of the rot at the heart of Government. Is it the case that anyone who puts a cross against any establishment party in 2024 or indeed, in council elections either, is as morally bankrupt as Government itself?

“The enemy is within the gates; it is with our own luxury, our own folly, our own criminality that we have to contend”

Marcus Tullius Cicero

It’s why I probably won’t vote next time. Our ‘democracy’ is a sham and if I turn out for the theatre of voting, I’m continuing to play a rigged game. People shouldn’t vote en masse next time. I’d love to see a Government try to run the country if only ten per cent of the population show up to vote.