We hear a lot about ‘decolonisation’ these days, even though practically all countries that were colonised by the European powers gained their independence decades ago. In contemporary parlance, ‘decolonisation’ means adding non-white authors to university reading lists and ensuring that ‘indigenous ways of knowing’ are reflected in the curriculum.

What’s more, there’s a whole academic field called ‘post-colonial studies’, which seeks to critically analyse Western colonialism. And while there’s nothing wrong with this in principle (we should analyse Western colonialism from a critical standpoint), many post-colonial scholars are less impartial critics than anti-Western activists.

They refuse to accept there was anything positive about Western colonialism. And when dissidents like Bruce Gilley or Nigel Biggar point out that there were positive aspects, those dissidents find themselves on the receiving end of censorious petitions signed by hundreds of their colleagues.

Such activism stifles intellectual debate and gives the false impression that Western colonialism was “a litany of racism, exploitation and massively murderous violence” – to quote Biggar.

One indication that the legacy of colonialism is far more mixed than most post-colonial scholars will admit comes from a recent study published in the British Journal of Political Science.

Andy Baker and David Cupery combined data from several cross-national surveys in which respondents in different countries were asked for their opinion about certain named foreign countries. The exact question varied from survey to survey. In one case, respondents were asked for their opinion “with zero expressing a very unfavorable opinion” and “100 expressing a very favorable opinion”. In another case, they were asked if they have a “have a very favorable, somewhat favorable, somewhat unfavorable or very unfavorable opinion”. Baker and Cuprey combined the various surveys using a technique called factor analysis.

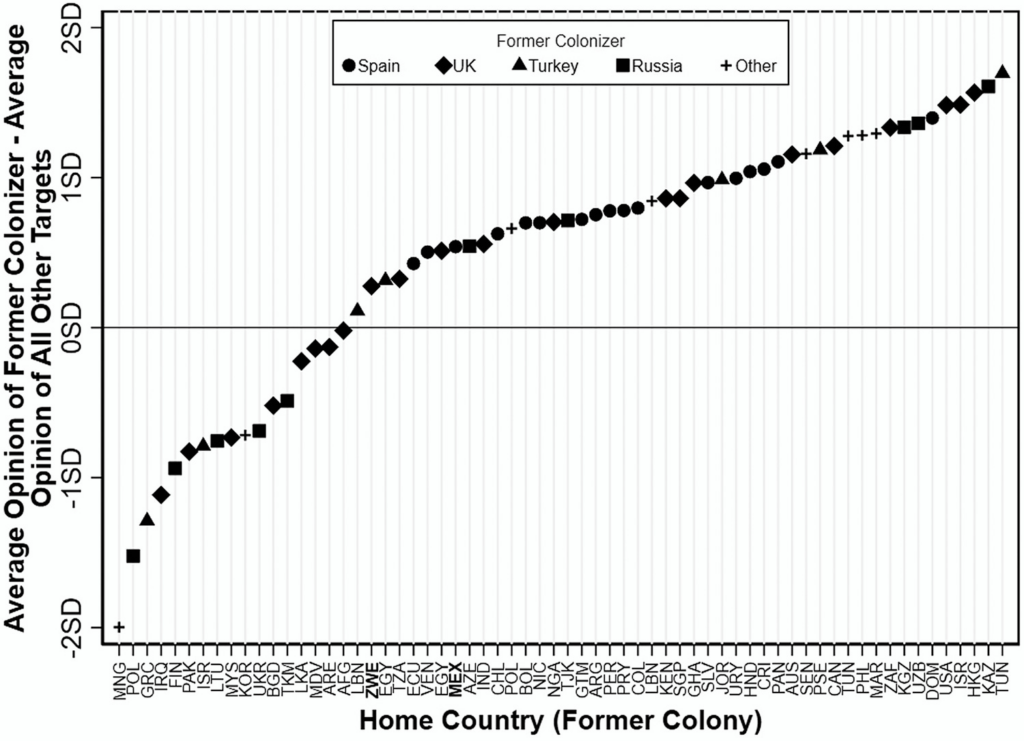

They were then able to calculate, for each country in their dataset that was a former colony, the average favourability toward that country’s coloniser minus the average favourability toward all other countries respondents were asked about. They call this quantity the ‘former-coloniser gap’.

Interestingly, they found that this gap was positive for a large majority of the former colonies in their dataset (47 out of 64). In other words, most former colonies have a more favourable opinion of their coloniser than they have of other countries. Results are shown in the chart below.

Looking at the left-hand side of the chart, we can see that Poles have an unfavourable view of Russia, Greeks have an unfavourable view of Turkey, and Iraqis have an unfavourable view of Britain. None of which is particularly surprising. What is surprising, though, is that these are exceptions. Most former colonies have a favourable view of their coloniser.

Further analysis revealed that the tendency for ‘former-coloniser gaps’ to be positive, rather than negative, could be explained by three main factors: colonisers tend to be democratic; they tend to have large economies; and they tend to trade more with their former colonies.

The authors interpret their findings in line with an ‘admiration hypothesis’, whereby former colonies’ views of their colonisers are characterised more by admiration than by animosity and resentment.

Add this study to all the post-colonial reading lists.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Wish the frogs would get on with that New Storming of the Bastille business. Long overdue.

I agree, I want to see Macron’s head on the guillotine!

Yes: as someone fond of older women, he should get on very well with Madame La Guillotine.

very humane.

Or better still, in the basket at the bottom.

…though I doubt even then its arrogant expression will change!

aux armes citoyens

I have read that Macron`s security detail resigned in protest -“Macron is not worth dying over”.

Time for the Generals to get involved.

Saw that tweeted from some dodgy looking sources. Anything in the mainstream, or in relatively reliable sources?

Well all the prominent “fact checking” sites now say it was bs too , so take with a pinch of salt.

Shame…

Fact checkers don’t confirm it, so it can’f be true, as if they ever would. We seem to have some weird comments on this one.

Nothing to do with “fact checkers”. But it’s implausible imo that such a story would have been kept out of a least the less globalist msm sources with no reason to protect the French regime (eg Fox, Sky News Australia) for this long if it were true.

Well somebody mentioned them, and I’m not referring to me. Fact checkers are to be treated as if they were funded by Bill Gates and come to think of it………..

Yes exactly.

Oh we believe “fact checkers” now.

‘Fact checkers’ are as biased as anyone else. When I hear those words I see an image of infinitely receding mirrors. Fact, Schmact.

Who checks the fact checkers?

The thugs/mercenaries who protect politicians already make up their mind about what is worth “dying over” when they accept the money.

Fair point.

How many of them would actually put their life on the line to protect these parasites, when push comes to shove? Keep in mind that they’re already paid and probably paid enough that never being hired again would pose no major concerns

Vichy comes back from the dead with a vengeance.

Liber….? What were those words again? They’re so hard to remember.

… I gather the Roast Beefs are having similar vocabulary problems with stuff like ‘Mother of the Fr…..???’

I heard the Vichy French were more horrible than the Nazis. Vive la resistance

They can always sing Deutschland uber alles

I saw this in the comment section in the Telegraph:

That comment won’t last long. It wouldn’t in The Guardian comments – deleted and all the comments related to it.

don’t tell me the Guardian are sell-outs?

Except they will only allow six months of freedom following prior infection, and of course you can only ever catch it once. On the other hand, the “vaccination” seems to confer around three weeks of a badly compromised immune system, followed by only 3-6 months of patchy non-sterile immunity.

This is nothing to do with a virus, they just desperately need 100% jabbed so that there is no control group.

If people haven’t got natural immunity by now, then clearly it isn’t needed.

So you get sent home if you’re not vaccinated? Sounds like an incentive NOT to take the jab!

There are much more worthwhile incentives, than being sent home. For example, avoiding a known to be dangerous, liability free vaccine, with unknown longer term effects, for an infection which is no risk to children, should make it a complete non-starter for those with a functioning brain. However, most parents will blithely offer up their children as potential sacrifice on the altar of Covid, with scarcely a thought. Utterly stupid and utterly disgraceful.

Er, do children have any rights in this? I’m sure there’s some human rights law (admittedly ignored by the secretive family courts)

Liberté, égalité, fraternité

Empty words in our modern world.

The Adventures of Macron & the Three Muskerhounds;

Googlé, Facébook et Twittér.

That was one of my favourite cartoons. Now get me that class one Scotch egg too and I’ll be happy!

Encouraging sign from France…

le jour de gloire est arrive

Utter insanity.

We now know that it isn’t the Delta variant that is causing the ‘breakthrough’ cases but also the ‘Gamma’ and ‘Epsilon’ variants, in fact wherever there is a high take up of the jabs there are ‘breakthrough’ cases of whatever is the current dominant variant doing the rounds.

But, of course, there must be some other explanation/scapegoat, rather than the ‘bleeding obvious’ (tm Fawlty Towers) even though the jab rate correlates perfectly.

On another note, I am now quite keen to advocate for, not only, vaccine passports, but a requirement for these to be worn clearly as a badge of compliance by jabees so that I can avoid them and so avoid being infected by the ignorant infectious who have no or insignificant symptoms, and thus feel entitled to spread their disease far and wide.

its tempting to want to avoid the vaxxed because they are a) superspreaders b) variant escape factories

but at the end of the day its just a sniffle – whatever variant we are talking about. I’ll hug the vaxxed (if they let me)

I’ve already hugged a couple of double vaxxed friends and Ive lived to tell the tale.

Most of them are utterly unhuggable.

no sweat for those of us who like to hug lepers

I feel such smug, pious folk as would wear something boasting of their ‘goodness’ should be avoided like the plague (or virus now?) at all costs.

No passports please. A big yellow star on their masks will do nicely.

Ladies & Gentlemen, I give you Marek’s Disease !!!

Could this be their inspiration? With the vaccinated becoming variant production lines it fits well with the Geert Vanden Bossche hypothesis of a soon to emerge super variant.

There is a good chance that Marek’s disease was one of their desired outcomes. It would be particularly evil and profitable if it were achievable with these “vaccines”, since they only seem to give 3-6 months of protection. However this coronavirus thankfully seems to be following its natural pressure to become less virulent.

Luckily, otherwise we, the unvaccinated, might soon all be dead.

I’m well alive. I’ve never felt so alive.

That’s encouragibg.

Encouraging, sorry.

We aren’t chickens and our immune systems have been honed over tens of thousands of years. What is more of a danger is for people to isolate away from the herd when we should be doing the opposite.

Vanden Bossche use exactly the same kind of factually inappropriate, highly emotionalized language all people trying to market “their corona” to further some end use. That’s he’s – compared to the CDC – a minority player doesn’t make him more trustworthy when employing the same methods.

I don’t care for what purpose I’m being told porkies. Everybody who tries to wield fear as a weapon in an argument is trying to coax someone else into doing something which is useless or detetrimental to him and benefits the fear wielder.

He also seems to be treating all the official data as factually correct (even though they are largely based on the highly unreliable PCR and LF tests).

I’ve never seen him refer to any data.

He regularly references an increase in the number of cases involving younger people – where do you think he’s getting the figures from? There’s only an important increase if the official numbers are taken at face value – they shouldn’t be in view of what is known of the unreliability of the PCR and LF tests.

There have been an increase in cases in younger people.

Just because a test might pick up a high proportion of False Positives it doesn’t mean it can’t detect a trend.

The positivity rate wouldn’t just increase for no reason – particularly when it’s followed by an uptick in hospital admissions. .

Vanden Bossche has made the point that mass vaccination during a pandemic is a huge risk. Luc Montagnier the Nobel prize winning virologist has made exactly the same point. Neither has made any reference to Marek’s disease.

GVB provides good reasons why it is possible for a virus mutation to create a variant which will evade vaccine-induced antibodies while those antibodies might still outcompete the body’s non-specific antibodies and cause serious disease.

If You think GVB’s language is “factually inappropriate” perhaps you could explain what you mean. But, bear in mind, he has posted responses to the drivel posted by Yeadon (who had no objections to the vaccines initially) and Sucharit Bhakdi.

Why all the hating on the mention of Marek’s Disease here? Seems to be a reasonable suggestion that the mass use of “leaky” vaccines (or quasi-vaccine treatments) like these covid vaccines could have similar consequences to the mass uses of leaky vaccines elsewhere, surely?

‘Leaky’ Vaccines Can Produce Stronger Versions of Viruses

I wrote that in a comment yesterday. Paraphrase:

Why would a treacherous virus suddenly breed harmless variants?

Viruses aren’t even alive, let alone capable of conscious actions, hence, labelling them as treacherous make no factual sense, it’s just supposed to sound scary to humans. For the same reason, they also don’t breed anything and they’re neither malicious nor hostile. They replicate by exploiting (parts of) the cellular reproduction mechanism of host bodies. This reproduction mechanism inherently introduces random errors. As these errors are random, there’s no reason why they shouldn’t end up decreasing virulence.

NB: Above is 515 character parapgraph dealing with single of GVB’s sentences which serves as a nice illustration that BS is always much easier to produce than to refute.

What exactly have Yeadon or Bhakdi, for that matter, said that was “drivel”.

The incentives are certainly present

So overall, it’s kind of like mafia-style protection – either you accept it, or you suffer the consequences. However, it’s worth mentioning that, as an individual, it is rather unwise to refuse mafia protection.

The vaccines work well, you reckon? Not for the growing number of people experiencing very serious side effects.

Serious side effects from vaccine are orders of magnitude less likely (like, 1:10000 for hospitalization or 1:50000 of death) than the side effects from covid (1:100 hospitalization).

Ah, not if you factor in the severe under-reporting on the Yellow card scheme. Yesterday, one of the DS contributors worked out that as a 29-year-old, he was 3 times more likely to die from the vaccine than from the virus!

There is not any proof of “severe underreporting”.

So the fact that hardly anyone is aware of it isn’t going to lead to under-reporting, then?

You are a fool. This is to do with the US reporting system, but similar patterns are evident in the UK:

https://scholar.google.co.uk/scholar?q=underreporting+in+vaers&hl=en&as_sdt=0&as_vis=1&oi=scholart

How about this for proof? An admission from the MHRA itself!

https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/yellow-card-please-help-to-reverse-the-decline-in-reporting-of-suspected-adverse-drug-reactions

There can be no proof of “severe underreporting” because if there was, it wouldn’t exist as the cases conjectured to be not reported would need to be reported in order to compare them to the reported ones.

D’oh!

You also need to get out more.

The government themselves said before Covid it was at about 10% of overall events.

“It is estimated that only 10% of serious reactions and between 2 and 4% of non-serious reactions are reported.”

Yellow Card: please help to reverse the decline in reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

So the out now is that “lessons have been learned” and since this notice was put out in 2019, the scheme has seen wild success in its aims.

The debate around these numbers is never discussed. No questions asked in parliament. So what are we to think?

There is the example of menstrual bleeding — in this case there was a single incident of massive reporting at the end of May; reporting rates went up tenfold just because of a small article in BBC radio 4’s ‘Woman’s Hour’. What is the real rate? No-one knows for sure, but example this certainly shows that the Yellow-Card system is mainly a measure of how enthusiastic people are to report side effects, not of the actual side effect rate.

There is absolutely no proof that Sars-Cov-2 exists in the wild, as it has never been isolated from a person who has been supposedly afflicted with Covid-19. Now if you want to talk about US coronavirus patents, then that’s a whole new ball game.

Risks from covid need to factor in the likelihood of catching it in the first place (a certainty in the case of taking the vaccine). And of course you can still get the virus if you’ve been vaccinated.

The numbers are questionable all round, and essentially for young people probably amount to “bugger all” in either case, but imo it’s extremely unlikely the risks from the vaccine are less than those from covid for children and young people at all, let alone by orders of magnitude.

And, of course, in the case of the vaccine there are very real concerns about unknown unknowns in the long term consequences, where we basically know nothing about what the effects of the vaccines will be. As far as covid is concerned, there’s no reason to suppose the long term risks are significantly different from those accompanying respiratory viruses in general.

Given the high transmissibility the risk of “catching it” during the upcoming autumn/winter season, especially if there are no contact restrictions, approaches certainty. The vaccination decision does not concern what happens in long-term, it concerns whether you want to risk hospitalization next season.

It’s true for young people the cost/benefit is entirely different than old. If you discount the “long covid” story and the reported 20% of hospitalized patients coming out with organ damage, that is.

So the way I see it, for old people the vaccination is “stop bitching and get it the hell as soon as you can” story, for young people it’s optional, but mostly harmless and possibly helpful.

So you’re willing to take your chances despite the lack of long term safety data (and now no control group)?

And you trust the stats you are using to assess risk and benefit?

What about people with specific medical issues e.g. history of autoimmune disorders? Who would you trust to give you accurate data on risks of covid to you vs risks of the vaccine? Your doctor? The government?

Well my GP practice sent a text with a link to a video clip with one of the GPs saying everyone must get the vaccine because “no one is safe until we are all safe”. If my GP can use this cliche I don’t feel I would get very far with a discussion about my concerns. So I feel my choice is to keep my head down, keep out of the way, and see where things are up to in the spring.

I was open-minded to start with, but for now I will wait, though I am not hopeful that accurate data will emerge to allow me to make a rational, evidence-based decision.

Yes I agree. Perhaps it might be that Valneva vaccine might prove a safer and better bet. I would prefer no vaccine at all but the coercion is enormous. I now feel I am some kind of deviant for not wanting these current vaccines and it’s not possible to have a conversation with many people so thank goodness for this website and people like you

These injections are not vaccines. They are clearly dangerous.

So there are no ifs and buts, they are intended to kill and maim.

C1984 has an IFR of 0.15%. I don’t need ANY pharmaceutical intervention to “protect” me from that level of risk.

I understand that position as a starting point.

With any questioning being cancelled and research retracted, it seems to be such a mess. I’ve seen people so sure of themselves taking more time to research how best to save £10 a month on their internet provider than the numbers on these vaccines.

Yet they shout loudest, so emboldened they are by the regime to demonise others who are “waiting for more data”

“no one is safe until we are all safe”

Anyone who can parrot that nonsense has no grasp of scientific reality.

It should also be noted that this is nothing but a rehash of the Brexit-phrase nothing is agreed until everything is agreed.

“Given the high transmissibility the risk of “catching it” during the upcoming autumn/winter season, especially if there are no contact restrictions, approaches certainty.”

Seems highly unlikely, given the rather low (comparable with other colds and flu’s) secondary attack rates even in household settings.

“If you discount the “long covid” story and the reported 20% of hospitalized patients coming out with organ damage, that is.“

These do seem likely to be mostly fairy stories based on a small core of truth and mostly on the widespread societal hysteria about this disease.

“So the way I see it, for old people the vaccination is “stop bitching and get it the hell as soon as you can” story, for young people it’s optional, but mostly harmless and possibly helpful.“

Not the way I see it, which is: for old people, get vaccinated if you are scared of a not particularly scary disease that mostly takes out those on their way out anyway, or if you want to desperately pretend to try to live forever, and for young people: you’d have to be literally insane to take these experimental treatments for something that basically doesn’t threaten you.

Thank you Mark, very well put. Those statements from rayc were all annoying me too

My partner and I were slightly reluctantly double jabbed back in May. Last week she had some nasty cold symptoms (sore nose and feeling poorly) and tested covid-positive. We live together, with all the close contact that implies, and I had to isolate. I have a negative PCR test and I followed up with a negative LFT. None of her other “close” contacts tested positive.

As you say a VERY low secondary attack rate. I believe it’s reckoned to be around 11%.

Also she was more poorly than we both had a mild bout in March 2020 – one, younger, close family member had all the classic symptoms including losing taste and smell for months. So much for the Astrz vaccine!

Are youa 77 wannabee?

Utter rubbish culled from the usual suspect sources.

also the long term is longer the younger you are, so the risks are actually higher the younger you are

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/06/210611174037.htm

If that RNA is written back into your genes it’s with you till you die.

If you can’t distinguish between Covid and SARS infection, you don’t know much about anything. AS shown by your faulty statistics.

“a sort of “tax on life” is established”

A trial run for the CO2 Homeopathy faithful.

You could well be mafia or 77th Brigade, not too much difference.

Any natural immunity will have fallen by the wayside in these farmed birds many generations ago. We are not yet at that stage, but I suspect that may be their aim. `

And perhaps because many are kept in heated barns with false day and night times to increase egg production and are in large numbers too maybe?

Yes, I thought it worth mentioning given the similarities.

Also see Gandon et al, Nature 414.

The evil being inflicted on children clearly has no boundaries.

Utterly disgusting depravity.

There will be no need for such measures in the UK. They will stab the poor kids on entry!

Children aged 1 to 15

A table showing when vaccines are offered to children aged 1 to 15

AgeVaccines1 yearHib/MenC (1st dose)

MMR (1st dose)

Pneumococcal (PCV) vaccine (2nd dose)

MenB (3rd dose)2 to 10 years

Flu vaccine (every year)

3 years and 4 monthsMMR (2nd dose)4-in-1 pre-school booster

12 to 13 yearsHPV vaccine

14 years3-in-1 teenage booster

MenACWY

The above is from the NHS website giving details of children’s vaccines. It seem such a lot to me who only had TB and polio vaccines. Looking at it my guess is people with children and young people themselves will be so used to seeing vaccines are normal things covid vaccines will just be another to add in.

I think the difference is that we don’t give vaccines for other viruses experienced in childhood like common cold, we consider them as normal parts of developing immunity and it would seem to me we should be considering covid as a childhood illness rather than a vaccine illness.

And all those vaccine have been through the full trial and approval process.

the cold is a corona virus

Some colds are coronaviruses…

Kids get so many vaccines at school. And yet people who are perhaps age 60 years and over now had only TB and polio, all the others have been introduced since this age group were at school, but these are the people who are going be the growing older age group in society. How did so many of us survive without these other vaccines?

I was one of the first diphtheria cohorts in the early 70s. I didn’t react well with it, and so younger siblings didn’t get it.

My kids have had the full gamut, other than flu. And after reading “Vaccines: truth, lies and controversy”, they won’t be getting the flu one and my son won’t get HPV.

I was wondering whether to read that book, so perhaps I will get it now you mention it. Thank you

Sophie if you don’t mind me asking what your advice would be about the flu jab and a child with asthma ( well controlled ) ? Is it advisable?

Well of course death rates were higher than in the 2020 “plague year”in every year prior to about 2008 (adjusting for age). A few decades back, nearly double the 2020 rate.

Those of us who remember those years, mostly recall them as not particularly scary or death-filled. I suppose the nervous modern yoof must think we were just living in a horror movie-scape and not noticing it…

Anyone know how many children in France (< 18yrs) have died from COVID without a pre-existing condition?

The same number as you currently have down votes i.e zero

So the French are now the vanguard of irrational tyrannical power grabs, closely followed by our fat fxck.

A month before the physical emblem of vaxed or unvaxed is introduced at this rate of depravity. We are wondering whether our escape timetable has to be brought forward.

Spaceflight? Suicide?

Based on the evidence so far here is what the vaccines accomplish:

As the evidence continues to roll in, it seems likely that the answer to all three of those will become “no”, at which point the government will be truly desperate.

If the answer to the first two ends up being no, vaccine passports or any distinction between vaxed and unvaxed has no logical basis. It would be 100% political.

1 – buy shares in pharma

2 – vaxx everyone

3 – pretend end of pandemic is due to vaccines rather than natural shift to less severe variants

4 – annihilate unvaxxed control group

5 – find you have created a human Marek’s disease

6 – everyone has to have 3 month boosters for life

7 – vaxx companies, shareholders and Satan all happy

Think you have hit the nail on the head. But possibly add some of the other horrors:

8 – introduce social credit system.

9 – make vaccines dependent on social credit scores.

10 – class one scotch egg as a meal.

11 – tin foil hats for valued members of resistance

Not just a meal, remember – a “substantial” meal…

substantial meal class one Scotch eggs – mmmmmm!!!

Must admit I love class one Scotch eggs – making me hungry!

I’m struggling to identify any aspect of the official response over the last 17 months which has a logical basis (in terms of health). There are, however, obvious other logical underpinnings!

Scotch eggs make happy!

Muzzles work really well to keep zombies frightened.

Vaxxes work really well to make zombies hate the unvaxxed.

Both presumably do what they were intended to do.

give me those class one Scotch eggs any day!

THAT IS AN ABSOLUTE DISGRACE!!

Macron truly is the worst – I can’t think of a leader I hate more (although Trudeau and Ardern are close)

what have the French done to deserve that turd lording over them?

if anyone thinks its ok to hug a granny you’d think it would be him

didn’t stop Hancock

Well, perhaps it is just proximity, but for me it is Bozo.

Manual Chevron?

I didn’t like Franky Holland much either.

The idiots voted for him. It was blindingly obvious he was a Globalist/Bankster stooge.

Tough call for me. I despise Biden, Boris, Macron, Merkel, Trudope, Ardern and their boss, Xi Jinping all equally. Although to call any of them, other than Jinping of course, ‘leaders’ would be a stretch

Does anyone know how schools in Sweden have coped? It would be interesting to know if their schools have used masks and whole class isolation.

They haven’t used masks. They haven’t isolated classes.

They did fine with no intervention’s, no masks etc.

Thanks Stewart and NC. What has happened to our schools and in Europe? Sweden seem ‘able to learn to live with’ covid but we seem determined not to.

1.95 million Swedish schoolchildren coped very well during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic:

• 69 deaths from all causes during exposure to Covid-19 from March to June 2020.

• 15 with Covid-19, including those with MIS-C admitted to ICU from March-June 2020.

• 4 of those 15 had an underlying chronic co-existing condition (2) Cancer, (1) Chronic Kidney Disease and (1) Haematology disease.

No Swedish school child died from Covid-19.

They used common sense, not masks and isolation (reference).

Thank you. They have proved it is possible so why can’t the rest of the world do this?

Macron made some good contacts on his way up.

Rio Ferdinand LMFAO

‘young global leader’ no less!

I was shocked at Dan Crenshaw though.

Rio’s at the wheel!

Quite a lot of Beards and Beard “wedders” in that list.

Oh boy, I’ve shouting about this for the last couple of weeks! I have an old “conspiracy theory” book which talks about the WEF, and in it, it also talks about organising a number of unknown Young Global Leaders, to engage in the “2020 Initiative” to formulate the “roadmap” to “spearhead” change! These Young Global Leaders will be part of “the WEF’s projection of the balance of power in the world is of 2020! ” Jacinda Ahern was also recognised at that time as a “Young Global Leader!” But hey, it’s all just a conspiracy theory…

Have put this on a couple of other threads but putting it here as well as utterly shocking if true.

Very interesting if true. Can anyone confirm this other than a twitter feed?

PFIZERLEAK: EXPOSING THE PFIZER MANUFACTURING AND SUPPLY AGREEMENT.

https://twitter.com/eh_den/status/1419653002818990085

Swedenborg posted it yesterday I believe. There was a whole twitler thread where it gave an analysis of what many of the clauses meant. Twitler has now censored the thread.

The analysis was very convincing.

Here you go:

https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1419653002818990085

Thanks baboon, nothing much gets past Swedenborg.

Thanks. This should be headline news. I wonder if UK column are aware of it?

I posted an analysis of the Albanian Contract with Pfizer that was the basis of the twitter thread plus link to the draft Contract in the CDC Mask U-turn comment section. Its too long to repeat here.

Its damning, absolutely damning. The Nations signing this contract have every incentive to cover up anything that leads to costs against Pfizer, and Pfizer have every incentive to spend a lot of money in making sure the likes of Ivermectin are never approved for Sars2/covid application.

Here is the summary and link to the Contract.

Comments: This contract is simply terrifying and puts the states at the mercy of Pfizer. Billions of doses ordered will be delivered with no way for states to stop the supply. The only way to break the contract is to prove the manufacturing defect, which is virtually impossible. The manufacturing process is not stabilized so it is impossible to demonstrate that the vaccines would not be compliant. Pfizer has total immunity and is not even responsible for the ineffectiveness of its vaccines or for the occurrence of side effects, short or long term. The amounts involved are such and the risks for States so disproportionate that it is now easy to understand why there is no pharmacovigilance. Lead frommajor studies of vaccine side effects would mean shooting themselves in the foot, because they would have to pay all the consequences.

The State will therefore do everything to minimize, hide, deny any side effects in order to avoid prosecution and having to pay for Pfizer. States have clearly put themselves at the service of the laboratory to the detriment of the health of their populations. Twitter thread containing link to original Albanian document

https://twitter.com/eh_den/status/1419660536657154059

What kind of muppet would agree to those terms in the first place? It beggars belief.

Some muppet who wasn’t spending their own money and felt safe that the waste would never be uncovered or if it was it would be too late and they’d be taken care of by the entity who they transferred all that taxpayer’s cash to..

Probably all the governments ordering the injections have been ordered to by those running this project: IMF, World Bank, Black Rock, WEF et al.

All Western governments are now tinpot lackeys of the above.

They obey or get the Magafuli treatment.

They are possibly over a barrel. Whatever threat has been made it is truly grave. Even now it shocks me to uncover what we are dealing with here.

“On Tuesday… the CDC announced it had again changed its guidance on masks, recommending once more that all Americans wear masks indoors in public spaces. The game-changer for the agency was data showing that vaccinated people infected with the highly infectious delta variant carry the same viral load as unvaccinated people who are infected, the Washington Post reported.”

lol

Actually, they carry an even higher viral load.

https://www.market-ticker.org/akcs-www?post=243051

Their fraudulent decision to cap the ct at 28 for the vaxxed only has backfired spectacularly in that regard, as that higher viral load now became visible.

Not that masks would have made, make or will ever make any difference at all in that regard.

The differentiation of masks for the unvaxxed but not for the vaxxed, or now again for the vaxxed, doesn’t even qualify as pseudo-science or can be related on a correlation, let alone causalation basis.

It is just voodoo/superstition/witchcraft/alchemy, aka Faucism.

It’s interesting to just see flat out lies in the MSM

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2021-07-covid-booster.html

That’ll be another boost for home schooling then.

Unintended consequences and all that.

US is already seeing a massive increase in home schooling away from the malign influence if the teaching unions / establishment

Just imagine if you were able to take the LEA student funding level as a tax-break.

As the funding is allegedly for the young persons education, it should follow the young person instead of being a Scrooge McDuck cashpile for the educational in crowd.

I’m afraid your knowledge about where the money goes is shrouded in cobwebs.

I imagined you’d be a promoter of state indoctrination as you’re still a believer in flat-earth economics.

Most here are sceptics of all coercion. marxism is the most coercive and consequently economically destructive of all the forms of rent-seeking.

France is lurching into civil war.

Once one regime topples, more will follow.

ah yes Tunisia. I’ve thought for a long time SAGE should consider the cost of war and political chaos. Instead, they plough on with apartheid

roll on the sixth republic

It’s all about reeducation and obedience.

Priming and conditioning people and in particular the young to abandon their individual rights, critical thinking ability and, above all, bodily autonomy.

To ensure the unquestioned rule of pseudo-progressive fascists and their modern day pseudo-medical fascism.

Social distancing is a torture practice, in particular for children.

We know that since Kaspar Hauser.

https://de.rt.com/meinung/121345-kaspar-hauser-jahr-corona-massnahmen/

And Germany’s health rulers, the insane RKI, are now openly advocating for brainwashing all children whilst in school by the means of teaching them regular lessons in Covidianism&co.

They just had to dust off a few brochures from the 1930s, when they were similarly active and involved already.

https://www.tichyseinblick.de/daili-es-sentials/rki-strategieplan-fuer-den-herbst-modellierungen-gesundheitserziehung/

Article on French opposition in ‘Spectator’ . Puts opposition at 35% , which is probably not too far off. Probably 35-50% in support. Which is why they are going hard for the kids to get to their ‘magical’ 70% jabbed.

https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/macron-s-war-on-covid-meets-resistance

35% of activists is more than enough. If a third of them take to the streets it will topple the regime.

Also that is 35% passionately and angrily against it, vs 35-50% who are probably mostly slightly in favour, apart from the fanatical few. I would think there are far more people against it who will do something about it than are for it and will try to stop them.

Very extreme, if the vaccinations work

So if I am double vaccinated in the UK – go to France on holiday and re-enter on my British passport I still have to self isolate (Amber plus) – but the bloke next to me on the plane – from the same place I spent two weeks in (but he lives in) doesn’t have to if he has an EU passport? If I was an ardent remainer who had discovered my EU roots and sourced an EU passport, then I could now use my EU passport to travel to France and back without any problem! Good luck squaring the circle of introducing Amber plus to Spain and Greece now Mr. Shapps….

Residents of Amber+ countries will have to isolate in the U.K. as will U.K. travellers.

https://hack-and-trace.me/ removed from DNS by health fascist collaborators.

https://hackntrace.xyz/

Segregation in the schools. the vaccine neither stops you spreading it or stops you getting it, can’t see the point

As if Macron wasn’t bad enough, that other globalist piece of shit, Biden, has just announced that we have a pandemic “because of the unvaccinated”. The pogrom has been given the green light.

Not the first time that senile, corrupt old twat has played that nasty game.

So if someone who is vaccinated gets a “positive” test the unvaccinated get sent home…geez its getting so ridiclous but we know the beast system is here and it will not stop now.