The threat of tropical mosquito-borne vector diseases becoming endemic in Britain in the near future made recent headlines in the unquestioning mainstream media, with particular pride-of-place given to the revelation that London could suffer endemic dengue fever transmission by 2060. Of course, like all good sandwich-board climate scare stories, this one has been walked around the park a few times in the past. In 2013, the Guardian reported that “leading health experts” were urging the Government to take action against the growing threat of mosquito-borne diseases, since “climate change could bring malaria to the U.K.”. Back in 2001, the newspaper reported British health officials had warned that malaria could return to southern counties “within 20 years” as the climate warms.

The latest catastrophising report comes from the U.K. Government’s Health Security Agency (UKHSA), led by Dame Jenny Harries. It is highly political in tone with Professor Isabel Oliver, Chief Scientific Officer at UKHSA noting that it “demonstrates the impact that climate change could have on our society if we don’t take decisive action”. It does nothing of the sort of course because, astonishingly, the UKHSA has based many of its headline-grabbing predictions on climate models fed with a presumption that temperatures will rise by 4-5°C in less than 80 years. Since global temperatures have barely moved much more than 0.15°C in the last 25 years, this 4-5°C high emissions pathway, known as RCP8.5, is little more than a highly implausible invention.

“Climate modelling under a high emissions scenario suggests that Aedes albopictus – a mosquito species that can transmit dengue fever, chikungunya virus and zika virus – has the potential to become established in most of England by the 2040s and 2050s, while most of Wales, Northern Ireland and parts of the Scottish Lowlands could also become suitable habitats later in this century,” says the report. Dr. Lea Berrang Ford, Head of Centre for Climate and Health Security at UKHSA, added that “a child born today will be in their working-age years when health impacts may peak or accelerate further, depending on how much we decarbonise now”.

Linking public health in this way using invented future temperature rises is a disgrace. It does a grave disservice to the British public who are entitled to receive timely and realistic advice on current and future health threats, not politically-driven scare stories based on unproven science and garbage-in, garbage-out climate models.

It is particularly disappointing to see the UKHSA, an executive agency of the Department of Health, making such a play of RCP8.5. In its latest assessment report, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change noted that “the likelihood of high emissions scenarios such as RCP8.5 or SSP5-8.5 [a later version] is considered low”. The UKHSA is using a ‘low likelihood’ prediction to make fanciful, politically-inspired claims of tropical disease epidemics to scare the young, in particular, to follow a collectivist Net Zero agenda. Regrettably, the RCP8.5 pathway is responsible for much of the ‘clickbait’ science that still dominates the mainstream media headlines, from the Gulf Stream collapsing, to all the coral suddenly dying in the oceans. For its part, the UKHSA describes RCP8.5 as a “plausible” scenario.

The science writer Roger Pielke Jnr. has long been a critic of its widespread misuse, noting that we can view it as one of the “most significant failures of scientific integrity in the 21st century so far”. His short explanation for how such an obvious corruption of the scientific process has been allowed to stand for so long is “groupthink fuelled by a misinformation campaign led by activist climate scientists”.

As I noted earlier, the vector tropical disease climate scare is dusted down at regular intervals. But the facts have refused to cooperate – since the U.K. Department of Health and the Guardian first told us in 2001 it could appear within 20 years, malaria has been keeping its long-term low profile.

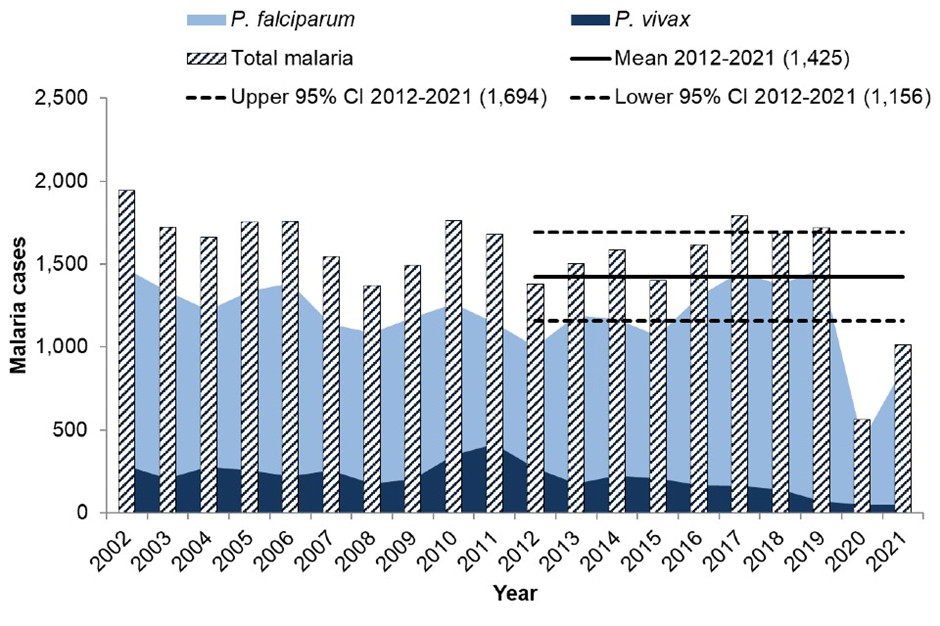

In June this year, the UKHSA issued a more sober assessment of malaria in the U.K. It noted that malaria “is not currently transmitted in the U.K.”, but travel-associated cases occur in those who have returned to or arrived in the U.K. from malaria-endemic areas. The above graph shows cases of malaria reported in the U.K. from 2002 to 2021. It shows they have remained fairly constant over the last 20 years, with major drops in the travel-restricted Covid years.

Chris Morrison is the Daily Sceptic’s Environment Editor.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Every decision involves a trade-off – which means that full data should be available and not waved away by a wave of an activists hand.

In my work, I’ve tried to obtain these sorts of data from official and/or reliable sources. It’s either extremely difficult or, more usually, the data is simply not available. And that’s before you have to face the possibility that some of the data is fake.

Perhaps windmill fires are as ‘rare’ as battery cars going up in flames and toxic smoke. There was a more unusual one where a battery scooter in the boot caught fire and burnt a normal car out.

‘exposed to the same flow of oxygen that fuels fire’

Glad they mentioned that. I’d have wondered otherwise …

And don’t ever forget ‘they are designed to catch the wind’

You learn something new everyday!

It does seem to be written for the ‘hard of thinking’ doesn’t it… also there’s a quote an engine was damaged… surely they mean generator?

Unless they have a motor to make the turbine go round on calm days, to create the impression it’s doing some good, and create a breeze to drive the next turbine downwind?

Don’t worry, I’m not being serious.

Joking aside, I wonder if they do have a small diesel generator as a power backup of last resort… it certain conditions they need to be able to brake the thing, or furl the blades (I think that’s the term used)

Don’t worry they are connected to the Grid! But if that fails there will be a problem.

That’s what I meant – say your wind farm of 100 turbines loses its grid connection and a storm is coming, they must have some inbuilt backup power to park them / protect them somehow or you could lose the lot. Maybe some stored air or similar + batteries for control gear

Except on the days when it is too windy to generate electricity……

Ohh… but no problem the con-companies still get paid

The smoke from that fire is reall pollution. What will the greenies say – nothing, I suspect.

Plus the carbon compounds.

Probably saved a few birds by burning down. Chris Packham should be happy!

Not for nothing some three hundred years ago were all those dark satanic mills powered by the high density, high gradient, high continuity hydrocarbon energy that superseded flaky windmills and waterwheels inherently subject to the whims of weather.

And three hundred years later, dimwit politicians and media still don’t get it.

Bring me my bow of burning coal, bring me my arrows of fire.

Bring me my arrow & I know where I’d shoot it…

More please.

What a good job wind energy is so cheap and plentiful. They’ll have plenty of money in the coffers to buy replacement turbines.

I’m in ironic mode today.

They destroy on so many levels and yet they are held to be benificent. You don’t need a clearer illustration of the Satanic nature of this agenda. You find it in every area of this project. Everything they produce is the very opposite of what it purports to be. The electric car is an increasingly conspicuous example. Just consider their conceit, the assumption that we would all just go along with this agenda and eat the bugs. It really shows you how much they are high on their own supply.

I’m sure the insurers have the data

“Firefighters arrived to find a well-developed fire involving a wind turbine…”

I’m certain this fire would have been visible from some miles away.

I tried, a few years ago, to find Health and Safety statistics for Big Wind. Both onshore and offshore.

For some strange reason, official statistics of serious injury and fatalities were then hard to find.

No doubt the HSE are now all over the case, such a blatantly high risk workplace!

I well remember how keen Her Majesty’s Mining Inspectorate were, quite rightly!

Surely, it couldn’t be the case that different H&S approaches were applied to different industries??

Add that environmental hazard to the thousands of EVs that are catching fire when it is least expected. The fire caused by a damaged or faulty battery is very toxic and incredibly difficult to put out.