The Institute for Fiscal Studies has released a 90-second video summarising its July 2023 report, which assesses Labour’s VAT class warfare against independent schools. It thinks it won’t cause significant pupil migration and will therefore raise about £1.5bn, which won’t much move the needle of benefit as regards education spending. I agree it won’t make much difference: the problems of failing schools and social mobility are substantially not about money and £1.5 billion wouldn’t go far to fix them.

It is quite wrong to speak with such certainty about pupil migration, where it assumes parents’ ability and willingness to soak up a 15-20% effective fee increase worth £1.5bn. It ought to tell us (and more importantly, the Labour Party) more about how bad economists are at forecasting the future, and what will happen to the public finances and to state schools if it is wrong. Some months ago I wrote to Luke Sibieta (who wrote the original report) outlining these concerns and I’ve also emailed Paul Johnson (featured in the video). I’m really looking forward to a response.

Apologies for being ever-so-slightly technical – TL;DR version is it’s impossible for anyone to know or quantify the effect on parents of a 20% tax, but the risks (which the IFS video doesn’t mention) are clearly large and on the downside.

This post outlines the problems with IFS demand forecasting.

The entire fiscal basis for this policy rests on this point, and we shouldn’t take it lying down. If VAT drives a significant number of current families out of independent schools, or future families never to sign up, the policy won’t make any money for the taxman. It could lose money while harming the state schools it claims to help.

As the think-tank EDSK outlined here, there is no knowing how many families will drop out. However at around the 25% level the net tax take is zero due mainly to the VAT foregone and the cost of state school admissions; even that is extremely generous because EDSK did not consider:

- (on the supply-side) the risk of school closures resulting in reduced income and national insurance contribution receipts on staff employment, reduced VAT receipts from expenditures, plus significant additional consequential pupil migration into the state sector.

- (on the demand-side) the risk that former feepayers now receiving

freetax-funded education decide to quit or reduce work and stop or reduce paying tax, in order to (1) choose leisure over material luxury, (2) provide academic and extracurricular support that the state sector doesn’t provide and (3) provide childcare around state school hours. - secondary and tertiary effects of the above, which you could read more about in Oxford Economics review of the independent schools’ impact on the economy.

If we’re going to introduce a policy that won’t (according to the IFS) really move the needle of financial benefit to state schools, we’d better be really confident about the costs, and that means we ought to be really confident about fee-paying parents staying put.

The Great IFS Guess

The IFS places huge emphasis on the past as a predictor of the future as regards the ‘price elasticity of demand’ (the tendency of customers to buy less private education given a price increase). They’re saying the rich will pay, they always do. Their report stated that “the effects of fee rises are quite weak” and “our best judgement is that it would be reasonable to assume that an effective VAT rate of 15% would lead to a 3-7% reduction in private school attendance”. This is based on the observation that “the demand for private schooling in the U.K. has hardly changed over the last 10 or 20 years” despite:

- a 20% real-terms rise in fees since 2010-11

- a 55% real-terms rise since 2003-04

For the sake of argument I was generously going to take those historical numbers for granted as I did in my previous post, but I’ve just realised I was quite wrong to do so for three reasons.

First, the report itself describes “only a small drop in the share of pupils attending private schools in England, from 7.1% in 2010 to 6.4% in 2022. This fall was mainly driven by a rising pupil population in the state-funded sector, with the number of pupils in private schools remaining around 560,000-570,000 in England over most of the 23 years”.

So we can back out the overall pupil population (state plus independent) as having grown 10% from 8.0 to 8.8 million over the twelve years. Demand itself increased. It’s not simply that schools have jacked up fees and customers have accepted it (proving, according to the IFS, movement along a very steeply-sloping demand curve). It’s (at least in part) that the demand conditions have changed, it’s a movement of the demand curve.

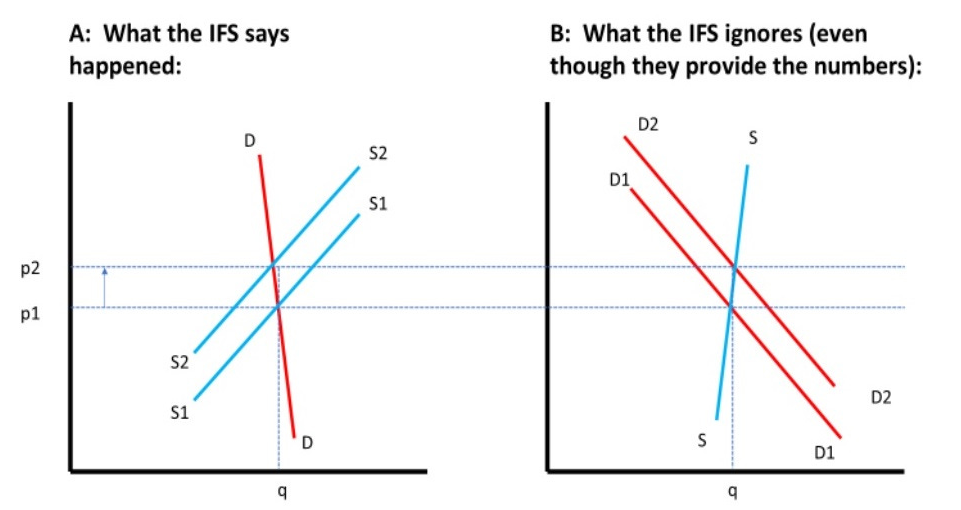

- On the left is what the IFS is saying happened – the schools jacked up price from p1 to p2 by moving supply from S1 to S2. Quantity q barely moved, therefore it knows the demand curve D must be very steep (which we call ‘inelastic’); if D was a shallower slope then quantity would have fallen.

- On the right is an increase in demand caused by that 10% population increase: an increase in demand from D1 to D2 causes a price increase p1 to p2 and a barely-perceptible change in quantity q. In fact it’s the supply curve S that is very steep (inelastic), and we know nothing about the elasticity of demand. Given a 10% increase in population, it’s pretty bold for the IFS to assert by omission that there was no such effect.

Both of these effects are probably at work. Both demand and supply are probably inelastic. It’s probably true that parents try hard for their kids, no matter what; it’s also probably true that supply doesn’t readily respond despite rising prices (the profit incentive isn’t prevalent, you need land, buildings, regulatory approval, a long time-horizon, and many parents won’t readily commit financially to a ‘start-up’).

But we really don’t know enough to assume away the entire effect of increased demand, let alone make quantitative ‘best judgements’ a.k.a. guesswork. This is week 3 of A-level economics, and the IFS fails.

Second, the report does not consider how many private school children are of non-resident/non-voting/non-taxpaying/non-British families. If the proportion of foreign or overseas families has grown at the expense of resident British taxpayers (which the IFS could have explored) then it indicates that U.K. customers have become less able or willing to pay the growing fees over the period. In fact it shows that those U.K. pupils have been displaced into the state sector – and the IFS’s assertions about demand being price-inelastic are rather problematic.

Third the IFS assumes that the education on offer has remained the same in both independent and state schools. Any enhancement in the former, or deterioration (perceived or actual) in the latter (in individual schools, noting that some top state schools have indeed closed the gap) would further challenge the assertion about demand being price-inelastic.

If we’re going to predict the future based on the past, a good start is to understand the past.

IFS doesn’t understand the future

Here’s a good Guardian article about economic forecasting. Sometimes, historical behaviour tells you something useful – for example, which asset classes are riskier, most of the time. But that’s ‘driving using the rear-view mirror’ – you could drive down a straight road that way, and (with a little skill) you’d be successful, right up to the point where the road bends.

Alternatively, as Hayek put it:

Confidence in the unlimited power of science is only too often based on a false belief that the scientific method consists in the application of a ready-made technique.

We can’t assume a straight road. We need to watch out for those bends. We need some curiosity, some sceptical challenge and scrutiny, before deciding the past is a guide to the future.

In terms of price and demand in markets for final goods and services, some of the conditions that could strongly encourage us to connect past and future are:

- It’s the same population of customers

- The customers have the same income and wealth constraints

- It’s exactly the same price shift, repeated (not cumulative or compounded, as in a 10% hike on top of a previous 10% hike, but repeated after reversion to the original)

- It’s exactly the same product, competing against the same array of alternatives on offer without major changes in price levels

- It’s a market with many data points (many customers, many frequent and repeated purchases) and easy switching both in and out of the product.

If you were selling forecourt petrol, you’d have a pretty decent idea what a 2p per litre price increase does to your sales. Similarly in supermarkets, you know what effect 2p per litre on milk does to sales and footfall. You probably routinely test the effect on various of your ‘fast-moving’ product lines. But you wouldn’t say because most customers accept 2p, that you’re confident they’ll accept another 2p, then another 2p, without ever reaching customers’ breaking-point or ‘last straw’.

Following its confident assessment of the past, the IFS does not explore whether the above conditions apply in education. These are significant reasons to doubt that the future will necessarily look like the past.

- It’s a different set of people (the 2025 cohort of parents compared to those of 2005-2010)

- Those people face a very different macroeconomy, which affects affordability; the IFS makes no mention of changes in house prices, interest rates, core inflation, fiscal drag, student debt, the waning of baby-boomer hand-me-down wealth, as though higher-earners are entirely immune to all these tectonic shifts

- The VAT increase is cumulative (it adds to, rather than being a repeat of, previous price hikes); it also sits on top of any inflation-driven pressures currently faced by the schools themselves.

- Education is characterised by strong relationships, high switching costs and few decision points; most families will make a school choice two or three times in their lives, while buying milk two or three times a week. The fact that existing parents stick with independent education or a specific school is a limited guide to whether the next generation of parents will choose it in the first place.

Back to those diagrams above. We never even knew the slope of the historic demand curve (the elasticity). Now we don’t know if the future demand curve (for the soon-to-register cohort) is even in the same place, nor do we know how it slopes, or if its slope might abruptly change as affordability reaches a ‘last straw’ point caused by Labour’s VAT.

As a result, we don’t know how families will respond to the effective price increase. It’s ‘brave’ of the IFS to assume they will just cough up, digging even deeper, rather than making different choices. Responsible policymaking should account for the risks the IFS is drastically wrong, and should explore the fiscal consequences on the demand and supply side.

Conclusion

The entire IFS paper is based on acceptance that ‘the rich will pay, they always do’. In this short blog, I question its understanding of past demand and its conviction it can predict the future.

If it’s wrong and many families withdraw into the state sector then the tax revenue falls away rapidly and could become strongly negative – and there won’t be any money to spend on improving state schools, before we even consider whether the state system is able to create the extra places, or whether it’s somehow desirable (in Labour’s opinion, not mine) that it does so.

The IFS paper should be withdrawn or rewritten with appropriate deference to uncertainty, encouraging policymakers to appraise risks beyond the ‘best-case scenario’ and to be honest about the fiscal consequences should those risks materialise.

Mr. Chips is a pseudonym for an employee of a private school. This article first appeared on his Substack page.

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.