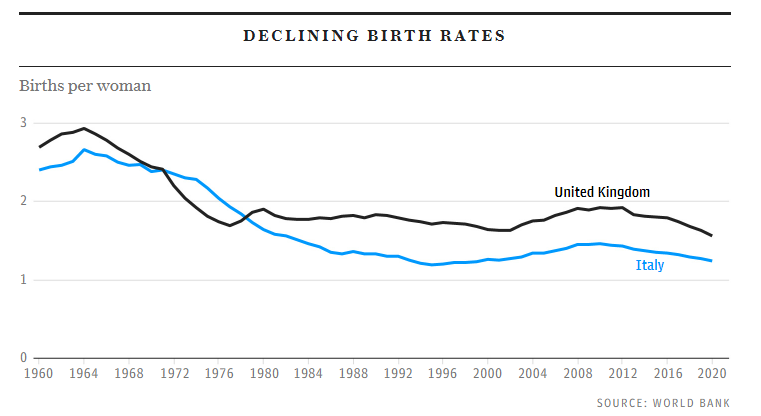

Across Europe, births have been below the replacement level for decades, leading to ageing societies that increasingly struggle to support their elderly populations and maintain a good standard of living. Polly Dunbar has been looking at the worrying statistics and what’s behind them in the Telegraph.

Recently, an apocalyptic phrase has been uttered over and over again by Italy’s political class: “demographic winter”. Almost every year since 1993, deaths in the country have outstripped births, causing a slow-motion crisis which has gradually reached critical mass.

Italy’s fertility rate is dropping so precipitously that by 2070, the population – currently 59 million – is forecast to fall by almost 12 million to 47.2 million.

The situation threatens to push the world’s eighth-largest economy into an ‘economic dark age’, without a workforce capable of funding its welfare state and the pensions of its older citizens.

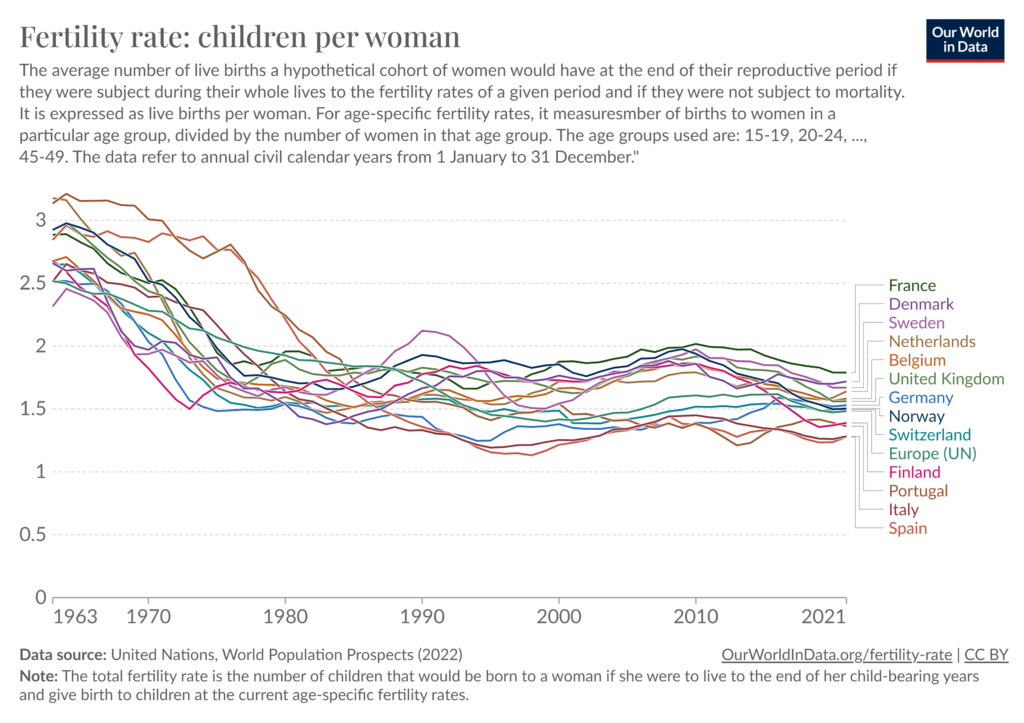

In fact, the picture across the whole of Europe’s population is bleak, with ominous implications for economic growth as well as pensions, healthcare and social services.

It is an ageing continent: by 2050, the share of people over 65 will rise to around 30% from around 20% today, says the European Commission.

And we’re not immune here, either. In Britain, the birth rate is at a record low. There were 605,479 live births in England and Wales last year, down 3.1% from 624,828 in 2021 – and the lowest number since 2002.

Almost a third of those births were to women born outside the U.K. The ONS has predicted that the U.K.’s natural population will start to decline in 2025, at which point there will be more deaths than births. …

The fertility rate has changed markedly across European countries in the past two decades. Between 2001 and 2021, it decreased in 11 of the 27 EU member states. Even France, the EU country with the highest fertility rate, recorded only 1.84 live births per woman, well below the magic number of 2.1 which demographers consider the benchmark of what’s needed to keep the population stable (called the substitution index.)

According to the EU’s Eurostat agency, Portugal, at 1.35, is projected to be the European country with the smallest proportion of children by 2050, with just 11.5% of the population expected to be under the age of 15.

Surveys show both men and women in Europe wish they had more children. There are many reasons they do not, including the trend towards starting a family later, but perhaps the biggest driving factor is economic uncertainty.

Worth reading in full.

Stephen J. Shaw recently looked at the issue for the Spectator. He reported the surprising finding that the problem stems not from people having smaller families – the average family size among those who have children has remained largely constant over recent decades – but from more people not having children at all.

Data showed that the preponderance of one-child families has barely changed in decades across these nations, leaving childlessness as the only possible reason for below-replacement birth rates. My hypothesis soon became that the shared explanation for low birth rates around the world was childlessness, and not smaller families.

The number of childless people in the U.K. has grown to one in four over the past five decades, yet the number of children that mothers are having has increased slightly, from 2.3 in the 1970s to 2.4 today. In Japan the figure for childlessness is one in three, yet 6% of mothers are having four or more children, exactly the same as in 1973. In Italy two in five women are childless, while the average mother is having 2.2 children, the same as 40 years ago. As for the U.S., the proportion of childless women is trending towards one in three, but the average mother is having 2.6 children, up from 2.4 in the 1970s.

This confirms that the idea we’re moving towards smaller families is simply a myth. Childlessness alone has driven our overall birth rates to ultra-low levels.

Since the demographic crisis stems from a growth in people not having children, rather than in those who have children having fewer, the solution must lie in understanding why up to a third of the population is now remaining childless. Is it by choice or through circumstance? Shaw thinks it’s mainly circumstance, citing research showing that “80% of people without children are childless through circumstance, with the most common reason being not having a partner at the right time”.

He notes statistics from an official U.S. database “of more than 5,000 women which has been the gold standard for researchers for decades”, showing that “between 93% and 96% of women consistently plan to become mothers in their early fertile years, many more than actually achieve that goal”.

If not having a partner at the right time is the issue, then the plummeting marriage rates and high divorce rates must be part of the picture.

Economic circumstances are usually blamed for falling birth rates, though if that was the critical factor you might expect everyone to have fewer children, not just the number who remain childless to increase. But perhaps unfavourable economic conditions are more likely to put people off starting a family than expanding one. A lack of affordable housing is often singled out as a barrier here.

Cheaper childcare and more flexible working is commonly touted as the solution, though the riddle there is that the countries with the most generous such provision, such as Scandinavia, are faring scarcely better than elsewhere.

Women and men in their 20s and 30s prioritising career and lifestyle over starting a family must be part of what’s behind the ‘never getting round to it’ and ‘never meeting the right person’ phenomenon.

I don’t suppose that the explosion in ‘non-heteronormative’ identities is helping much either.

What do you think – what’s behind the Western birth rate crisis, and what can be done to turn things around?

To join in with the discussion please make a donation to The Daily Sceptic.

Profanity and abuse will be removed and may lead to a permanent ban.

Everything about the WHO is suspect.

it always makes me shake my head when you hear people and the media say “india has had more deaths than the UK and scare people with supposed high figures” well yes, but india has different factors, i.e. the population of at least 1.4 billion, india’s hygiene and sanitary conditions are considered worse than a lot of Weston countries and also the general health conditions and diseases are also poorer. When the Who and the media spout big figures and ignore the many other factors it really is disingenuous.

Interestingly, you would think Covid would have had a bigger impact on California’s large homeless population.

Two articles on the WHO figures today. On one hand we are to take the data about Sweden seriously but not the data about India. Personally, I’m taking it all with a large pinch of salt.

Indeed, we seem to be picking cherries and sour grapes somewhat arbitrarily.

Except that the data for Sweden is far more likely to be accurate than the guesstimates for India

The Indian’s secret was vindaloo.

Vindaloo takes no prisoners.

More objectively likely, or more helpful to our preferred narrative?

The deaths in India need to be adjusted in order to fit in with The Science (the computer models).

They are having similar problems with the recorded global temperatures, turns out the weather is a climate change denier, they will cancel the weather’s Twitter account asap.

The WHO seems like a bigger version of the EU – out of touch, irrelevant, and a law unto itself.

The WHO is significantly worse. It’s an unelected gremium of so-called public health experts with the ambition to dicate government policy globally down to the level of who is when allowed to talk to whom and how people must dress in public. This is based on the notion that globally acting health bureaucrats get to decide which human acitivies are essential and which aren’t and can thus be harmlessly prohibited. Considering that people’s lives are usually tighty coupled to there jobs, this basically means grouping people into essential and inessential ones. The essential ones are allowed to work. The others are supposed to remain at home on often meagre government handouts financed by printing money or accumulating debts.

And it gets more evil than that: The WHO would also like to see universal, mandatory COVID vaccination. Even in the best case (which is far from the actual case), a vaccine will always kill some people. Hence, forcing people to get vaccinated is equivalent to decreeing that some of them are so inessential that it’s ok to put them to death by injection.

Lead by a terrorist…

What could possibly go wrong?

Still the most fundamental aspect of this is that no new pathogenic virus was properly isolated from any sick individuals in China, there was no proof of a new virus that caused a new disease.

When you look into the topic it turns out that virology is a complete joke of a science.

What they call isolation really is a fraud, they don’t isolate anything, they simply mix a sputum sample from a sick patient, mix it with monkey kidney cells as a cell culture host and then starve those cells and poison them with nephrotoxic antibiotics, when the kidney cells die they cliam that it but be virus wot done it.

From there they let a computer analyse all the gentic debris from the toxic soup and get the computer to piece together every possible combination that these bits could convievably make up, they then declare one of these made up sequences to be the new virus.

This is why they have an endless number of variants, the computers can generate endless different possible combinations and the virologists can keep claiming which ever ones they like as being significant.

The whole thing is a colossal fraud as are the vaccines that are claimed to combat these claimed viral infections.

Don’t fall for the “viruses don’t exist” scam either. There is pathogenic contagion that we call viruses, they just understand very little about them. The part they really don’t like to talk about is “terrain”, the health of the individual plays a much bigger part in how successful a virus is than any vaccine.

When humans play god disaster often follows.

Matthew Syed has written an absolutely appalling article in the Sunday Times using the WHO estimates to ‘prove’ how reasonable the UK government’s actions were/are. He also has a swipe at this website and all who ‘sail in her’ ( calling it by its old name).

I commented, needless to say my comment has been removed. The Times doesn’t like the truth. Goodness knows what the interweb will be like with the ‘on-line harms’ legislation.

the online harms bill ensures access to100% state viewpoints at all times, no exceptions.

VPN.

I didn’t realise we had been namechecked. I always assumed we were too small for anyone to notice. Evidently not. Excellent – a swipe shows we’ve hit a nerve and got people worried.

Yes, Syed accuses us of cherrypicking data!

Gave me a good chortle after what we have seen with government statistics.

Mark Woolhouse, a senior government scientist wrote a book about the Covid debacle; appropriately titled “The Year the World went Mad”. He concludes that the lockdowns were not necessary.

They’re just finishing the job.

They exaggerated the risk people were facing from a new pathogen and they are now exaggerating the total deaths. They are writing history, in preparation for the future and leaving no lose ends:

– The virus was super dangerous

– Lockdowns, masks, tests and vaccines saved us.

– Millions still died because we were slow to act.

– In the future we must act very quickly.so that we don’t have 15 million deaths.

That’s the story they are going with and they have the force of international institutions, the corporate media, national governments and major corporations to make sure their version is firmly established.

Even with their bloated estimates of death the claimed virus was still a damp squib, but they have injected billions of people with their poisons so their work is done.

They have left an enormous number of loose ends, and they will unravel. We just have to keep pulling on them.

One of the best articles I’ve seen linked to by DS is this one which concerns itself with the Italians kick-starting the covid scam in the West.

If you read it, pay close attention to the section that talks about how the main mechanism of the fraud, the test kit, was developed in Italy in cooperation with the communist Chinese.

It wasn’t long ago MI5 admitted the communist Chinese has infiltrated Westminster.

“In the words of Neil Ferguson, architect of the wildly-inaccurate Covid models that sent the world into a tailspin:

A single sentence said it all – I will never forget it.

The fact that Ferguson felt so secure in uttering it says it all really – that his position, and that of those he advised was unchallengeable, and that he can have had so little cop on to let the cat out of the bag like that in a televised interview – so what does that say about the quality of his modeling?

Great article BTW. You are right – one of the best DS has linked to

‘The public sector scores high on petty corruption but low on efficiency. The public health service is risible’…

Are they talking about India or the UK?

And where was the header picture taken – West Bromwich or Bethnal Green?

Countries with reliable reporting systems, if not with reliable reporting, are showing mostly little above average, or even below.

Nobody in authority tells the truth.

What is also highly suspicious is that the evil cretinous scientists are claiming the spike in hepatitis in children may be linked to pet dogs.

Let’s ignore the fact the world has been forced to lockdown over the last two years while politicians (and undoubtedly the scientists themselves) partied and carried on with their lives as normal.

No they need a scapegoat and they want to destroy another joy we have in our lives.

I’ve meanwhile read a couple of arguments that keeping of pets should be prohibited because it would be to damaging the the climate.

Yes it’s quite clear the great reset includes stripping us of pets. Well they can fuck off with their fraud. I will be buying a pup within the next few months.

Can’t heklp but suspect they are taking the lead from China, where pets have been killed byt “the authorities” when forcing their owners into quarantine.Presumably they saw that it was yet another effective way to demoralise people.

I’m sure you might remember in the early days of the covid scam, the dodgy scientists were talking about pets being carriers of covid. Such warnings fizzled away from the scientists poisonous lips, but the memory remained.

Maybe they realised this was one step too far too soon and didn’t pursue it.

Maybe it was the first nudge, while the hepatitis theory is the second nudge, and perhaps the third nudge will be the final one where they’ve effectively granted themselves permission to confiscate our pets ‘for our own safety’.

They will have deemed the public suitably brainwashed by this point to be more willing to give up their beloved dog.

Do you think the famous dog owners among TPTB will be “giving up” their dogs? or having them forcibly taken from them?

The WHO has made healthcare in the 1st world countries worse, they should stick to countries who actually need them

What we had here may have made developed country healthcare worse than typical care in India or Africa.

Anyone involved in the flogging of the fake vaccines is lying. Don’t believe a word they say and do not get any more jabs. You put your health and life at risk with this poison.

Anything these monsters want is for certain not anything you want.

Indeed; all in accordance with the UN policy of population reduction.

Recent BBC Article on Excess Death – Explained from the DATA!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2oq8-mOldEg

Remember, whatever nonsense they try to impose upon us in the future:

JUST SAY NO!

Highly suspect organisation produces highly suspect data. Well, that’s a surprise – NOT

The WHO is clearly one of our enemy within. Anything that they publish is to be treated with suspicion and extreme scepticism. A truly evil organisation; same as the UN and WEF.

Thank you for an excellent article.The WHO figures is based on a model which is absurd for countries with reliable real world data.Look at the Nordic countries with reliable data and Sweden with the world’s oldest and also the world’s most reliable death data.How many non discovered deaths of covid in a country with the most reliable death statistics did WHO find with their model? So many that they said Sweden was highest in the Nordic countries.

Nordic countries don’t need WHO estimates.They have real data.See below age stand. adjusted excess mortality.Sweden below Denmark,Finland(both LD the latter more so)and Norway lowest.

Do you believe Nordic raw data or WHO model?

‘He who pays the piper plays the tune’….Gates has his song sheet and the “terrible” pandemic narrative must be kept uppermost in minds.

India used Ivermectin to treat Covid patients so it’s very important to the WHO that India is identified as having one of the worst outcomes from the Scamdemic.

The WHO has to punish India for using Ivermectin and undermining the “WHO Official” view that Ivermectin doesn’t work.

I am sure someone will correct me if I am wrong but didn’t Japan also se ivermectin?

But they still believe China on 5,000 deaths???

Doesn’t make sense.

But having said that none of the ‘rona crap makes any sense.